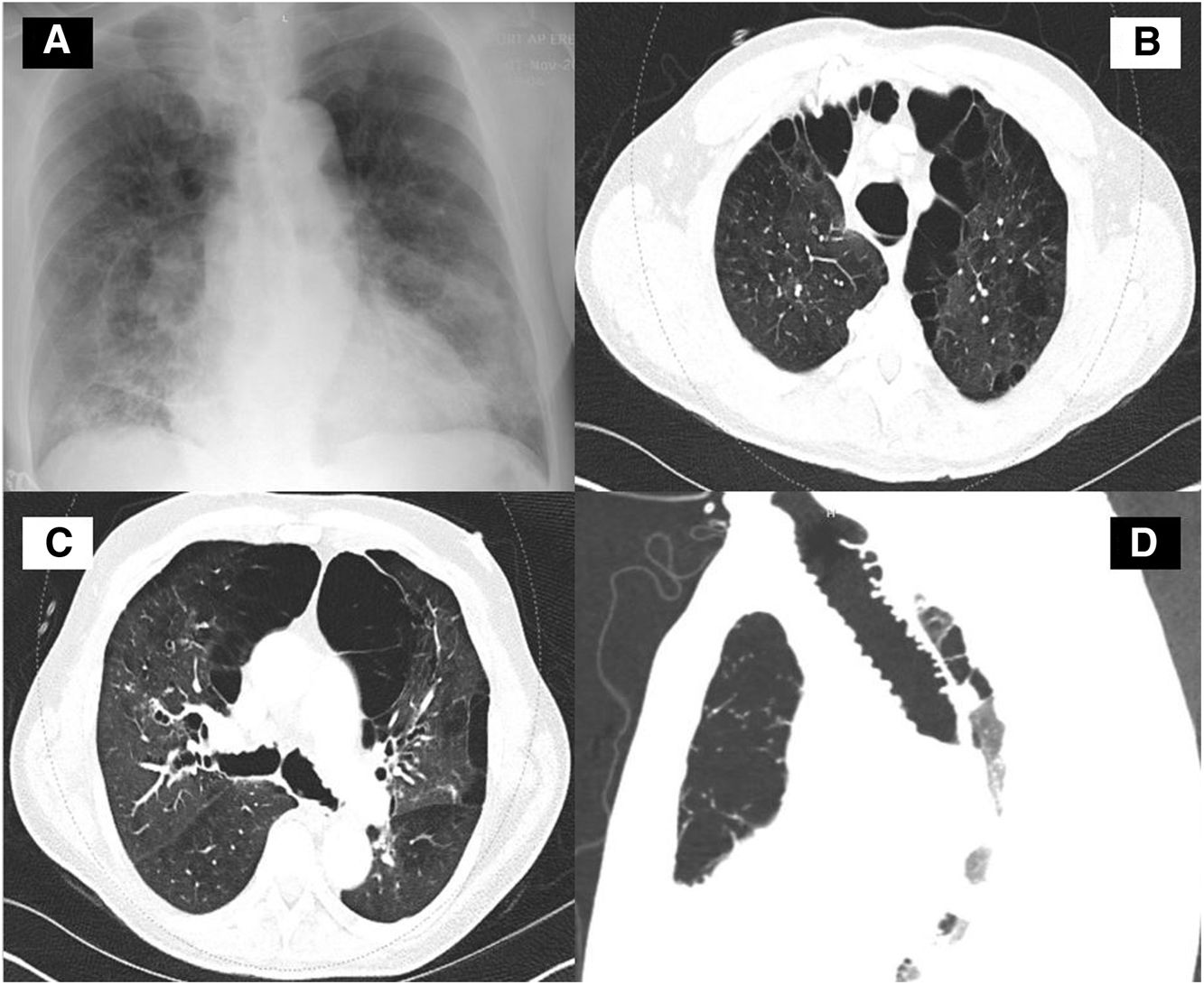

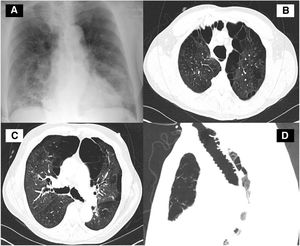

A 65-year-old man with a past medical history of recurrent pneumonia up to 8 times in the past 5 years presented to our institution with the chief complaint of a productive cough and shortness of breath over the preceding 2 weeks. Physical examination was remarkable with crackle heard on auscultation of both lungs. Complete blood count was remarkable for leukocytosis. The comprehensive metabolic panel was unremarkable. Chest radiography (Fig. 1A), demonstrated peripheral opacities in the mid and lower lung zones bilaterally. Computerized tomography (CT) of the chest revealed dilation of the trachea (Fig. 1B and D) and bronchiomegaly (Fig. 1C) with severe bullous paraseptal emphysema. Groundglass opacification and nodular consolidation right middle lobe. The clinical history of recurrent chest infections and a combination of imaging findings were consistent with Mounier-Kuhn Syndrome (MKS). The patient was treated with antibiotic and educated to improve airway clearance techniques.

(A) Chest radiograph revealed peripheral opacities in the mid and lower lung zones bilaterally. (B) Thoracic CT at a level above the aortic arch shows tracheomegaly severe bullous paraseptal emphysema. Groundglass opacification and nodular consolidation right middle lobe. (C) Thoracic CT at a level slightly below Carina demonstrated dilated right and left main bronchi with severe bullous paraseptal emphysema. Groundglass opacification and nodular consolidation right middle lobe. (D) CT image of the trachea (sagittal view) showing tracheomegaly.

The MKS is a rare disorder characterized by the enlarged trachea and main bronchi. It was first described by Pierre-Louis Mounier-Kuhn in 1937 associated with recurrent chest infections1 and anatomically described as tracheobronchomegaly (TBM) in 1962.1 The diagnosis can be made on CT by measuring the diameter of the airway. Woodring et al. suggested the following diagnostic criteria for tracheomegaly in adults based on chest radiography tracheal transverse diameter>25mm and sagittal diameter>27mm in males and, tracheal transverse diameter>21mm and sagittal diameter>23mm in the female.2 Different criteria have been suggested diameter of the trachea, right main bronchus, or left main bronchus that exceeds 3.0, 2.4, or 2.3cm, respectively on a standard chest radiograph or bronchogram.3 The diameters in our case were 3.5cm, 2.5cm, and 2.4cm, respectively, fulfilling the diagnostic criteria. This disease is thought to occur from atrophy of the elastic fibers of the trachea and bronchi, leading to thinning of the smooth muscle, and ultimately causing the trachea to become flaccid, dilated and develop tracheobronchomalacia.1 In mild cases, patients are asymptomatic or present only with chronic cough. In rare, severe cases, patients may suffer from pulmonary obstructive diseases such as bronchiectasis.2 Treatment is mainly supportive. Chest physiotherapy can be proposed to improve mucociliary clearance and antibiotics are administered for the treatment of pulmonary infections. Some patients may benefit from noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation, airway stenting, and surgical tracheoplasty.1

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestNone declared.