Methotrexate (MTX) is an analog of folic acid with antiproliferative and immunomodulating effects.1 Low-dose MTX therapy is a well-recognized treatment for various inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease.2 More than 20 years ago, the clinical efficacy of MTX was also established for steroid-dependent Crohn's disease (CD).3 Pulmonary toxicity is a rare side effect of MTX, which clinically is characterized by the new onset of dyspnea, dry cough, and fever and usually presents radiologically as an acute interstitial pneumonitis.4 Pneumonitis is a serious and unpredictable adverse event of treatment with MTX that may become life-threatening.5 Since the first description in 1969,6 Imokawa et al.7 collected 123 cases of MTX-induced pneumonitis published in the English language literature and added the description of 9 further cases. Cancer and leukemia were the underlying diseases in most patients (64.4%) followed by psoriasis (7.6%) and rheumatoid arthritis (6.1%). However, no case of pneumonitis associated with MTX therapy in patients with CD was identified in this clinical series. We here describe the case of a woman with ileocecal CD who presented with pneumonitis after 10 months of treatment with MTX. In a review of the literature, we were able to collect only three cases of MTX-induced pneumonitis in patients with CD,8–10 although one of these cases has been published twice.8,11 A review of salient clinical findings of CD patients with MTX-induced pneumonitis is also presented.

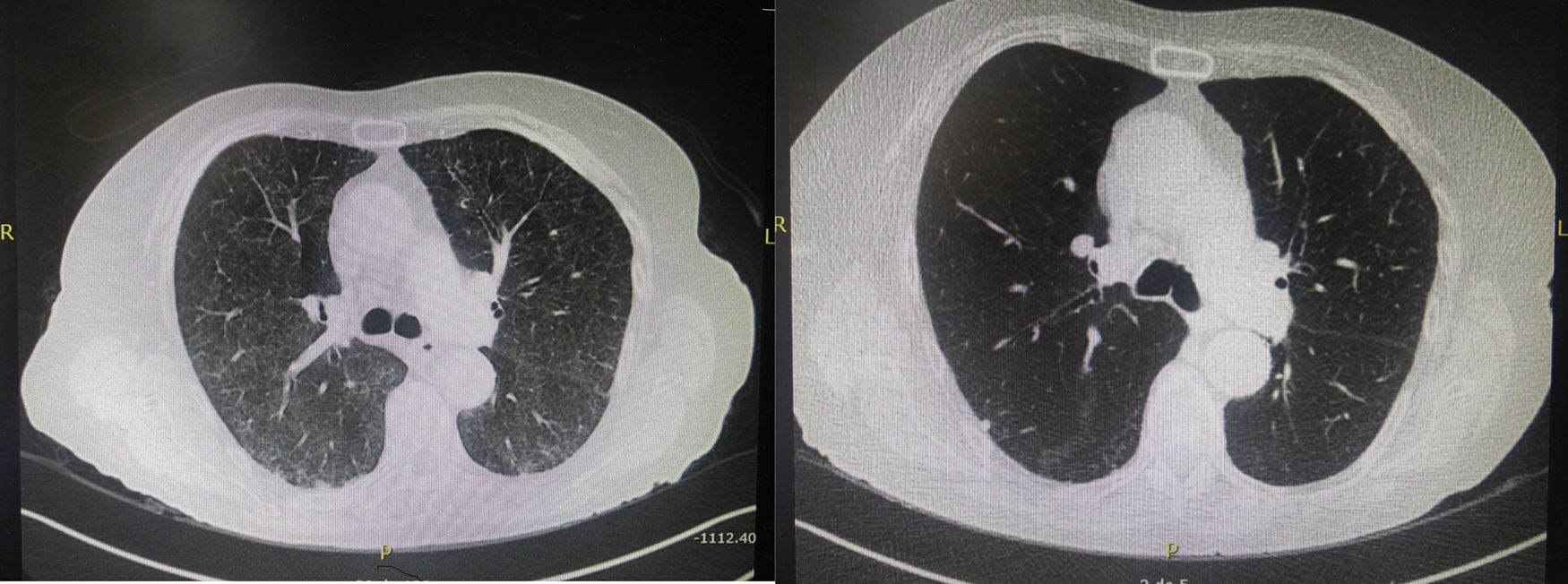

A 79-year-woman was followed up at the Gastroenterology Service of our hospital since 2011 when CD was diagnosed. The patient presented with an acute episode of intestinal occlusion and underwent diagnostic and therapeutic laparotomy. An inflammatory stenosing mass of 4cm in diameter, located at 25cm of the ileocecal valve was found and excised. Histological examination of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of CD. Postoperatively, the patient started treatment with azathioprine but it was withdrawn shortly after because of symptoms of intolerance. Therapeutic options were discussed with the patient, and treatment with MTX at doses of 25mg per week subcutaneously was initiated. The drug was well tolerated and complete remission of the disease was achieved. Ten months after starting treatment with MTX, she was admitted to the hospital because of persistent dry cough and dyspnea, which have been present for one month. There was no history of fever or alteration of her general condition. Physical examination was unrevealing and routine laboratory studies including blood cell count, liver and renal function tests, and biochemical profile with serological tests and antibodies against main pulmonary pathogens were in the normal range. The sputum was negative including bacteria, mycobacteria, viruses, and fungi. Chest roentgenogram did not disclose abnormal findings. A high-resolution chest CT scan showed diffuse parenchymal ground-glass opacities with subpleural reticulation, predominantly in the upper lobe of the right lung (Fig. 1). Bronchoscopy was negative, with absence of malignant cells in the cytological examination and no evidence of bacterial, viral, mycobacterial, or fungal infections in cultures. MTX-related toxicity was suspected, and treatment was discontinued. High dose oral steroids were given and clinical symptoms promptly improved. At 3 months after MTX withdrawal, a high-resolution CT scan was normal. The patient was then treated with 6-mercaptopurine and budesonide for 3 months. Budesonide was then discontinued and the patient in currently maintained on clinical remission with 6-mercaptupurine monotherapy.

Since preliminary data published in 19896 showing that MTX had some efficacy for the treatment of patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease,12 evidence supports the view that MTX is a useful alternative in patients with active CD unresponsive to standard immunosuppressive drug treatment.13 MTX at dose of 25mg/week is effective at inducing remission and in allowing steroid tapering for steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent patients with CD.14 Bone marrow suppression, nausea, vomiting, hepatic fibrosis, and lung toxicity are potential adverse effects associated with low dose MTX therapy, and have been mostly documented in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Lung toxicity due to MTX in patients with CD treated with this drug has been exceptionally reported, with only three previous cases published in the literature.8–10 All patients were women, aged between 36 and 69 years, and presented with dyspnea and non-productive cough, with restrictive respiratory insufficiency in one patient.8 Also, treatment with MTX was indicated in the context of severe colitis, ileo-colitis or ileo-pancolitis in steroid-dependence or intolerance to infliximab or azathioprine. The time elapsed between the initial dose of MTX and presenting symptoms was short (2 and 10 days) in two cases8,10 after 18 months of drug administration in one case9 and after 10 months in our patient. Diagnosis was made by the presence of ground-glass opacities on chest CT. Elevated cell counts (lymphocytes, eosinophils) were noted on bronchoalveolar lavage in two cases.8,10 Alarcon et al.15 identified risk factors for MTX pneumonitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, including older age, diabetes, rheumatoid pleuropulmonary involvement previous use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and hypoalbuminemia. Older age represents the strongest predictor of lung injury, the risk being double in 50–59 year-old patients and six-fold in patients over 60 years-old.15 The patient reported by Trivedi et al.10 was 64 years-old, and our patient was 69 years-old. However, neither diabetes nor hypoalbuminemia or pre-existing pulmonary diseases were presented in CD patients with MTX pneumonitis. All these cases met diagnostic criteria for MTX pneumonitis.11 In our patient, the diagnosis of MTX-induced pneumonitis can be considered unequivocal according to the radiologic evidence of pulmonary interstitial infiltrates, the negative blood cultures (major criteria 2 and 3) in conjunction with 3 minor criteria (shortness of breath for <8 weeks, non-productive cough, and normal leukocyte count [<15,000cells/mm3]). A complete resolution of pneumonitis was observed by CT scan at 3 months after MTX withdrawal and a course of systemic steroids. In the routine daily practice, diagnosis can be established by a compatible clinical history, radiological images of ground-glass opacities, and presence of lymphocytes and/or eosinophils and increased CD4/CD8 ratio in BAL samples. Lung biopsy is rarely necessary but pulmonary histology is characterized by alveolitis with epithelial cell hyperplasia and eventually, small granulomas and eosinophilic infiltration.