The risk stratification of patients in the 2017 edition of the Spanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC)1 is simpler than that in the first edition.2 Although the multidimensional indices, BODE and BODEx, have shown good ability to predict mortality, they are rarely used in clinical practice. For this reason, the new GesEPOC guidelines propose a dichotomous stratification of high and low risk, according to the presence or absence of three risk factors: FEV1<50%, mMRC functional dyspnea grade >2 (or = 2 in patients already receiving bronchodilators), and a history of exacerbations. It occurred to us that a quantitative classification that took into account the number of risk factors present in each patient could offer advantages with respect to the dichotomous classification, allowing patients to be classified into escalating risk categories, in a similar manner to the BODE/BODEx indices, while being easier to apply in clinical practice than stratification based on multidimensional indices.

In order to verify this hypothesis, we performed a retrospective study of all patients seen in the dedicated COPD clinic of a university hospital. The study population comprised all consecutive patients with a diagnosis of COPD according to the GOLD initiative criteria3 and a history of smoking (cumulative exposure >10 pack-years), seen between January 2008 and April 2017 (726 subjects). The patients were selected from a healthcare database in which body mass index, lung function, mMRC functional grade (with and without treatment), history of exacerbations in the year prior to the index date (date of the first clinic visit), and moderate (requiring treatment with antibiotics or steroids) or severe exacerbations (requiring attention in the emergency room or admission) were systematically recorded. Patients were classified according to: (1) a quantitative scale using BODEx index quartiles;2 (2) the high–low risk dichotomous scale recommended by GesEPOC 2017;1 and (3) a 4-level quantitative scale, on the basis of the number of risk factors present in each patient (0, 1, 2 or 3). We performed a survival analysis for the three scales according to the Kaplan–Meier method, using the log-rank test for the comparison of survival curves. A Cox's proportional hazards analysis was performed, using age and comorbidity measured by the Charlson index as covariates. We compared the ability of the two quantitative scales to predict overall mortality using receiver operator curves (ROC), comparing the areas with the DeLong method.4

Patients were excluded due to missing study variables (59), or because they were lost to follow-up (30), followed up for <6 months (25), or underwent lung transplantation (4). Study population: 667 subjects, 597 men (89.5%); age: 68.3 ±9.5 years; FEV1%: 49.9 ±17.2. SpO2: 93.1 ±4.6%. Patients with SpO2<90%: 115 (17.2%). BMI: 28.2±15.1kg/m2. Classification by severity of airflow obstruction: GOLD 1, 36 (5.3%); GOLD 2, 292 (43.7%); GOLD 3, 246 (36.8%); GOLD 4, 93 (13.9%). BODEx: 2.6±1.9. Patients with Charlson index >1: 319 (47.8%). Follow-up time: 47.9±23.8 months. In total, 490 subjects (73.4%) were classified as high risk according to GesEPOC 2017 (215 subjects had a single risk factor, 143 had 2, and 132 had 3 risk factors). There were 149 deaths (22.3%), within a mean of 39.0±22.4 months after the first visit.

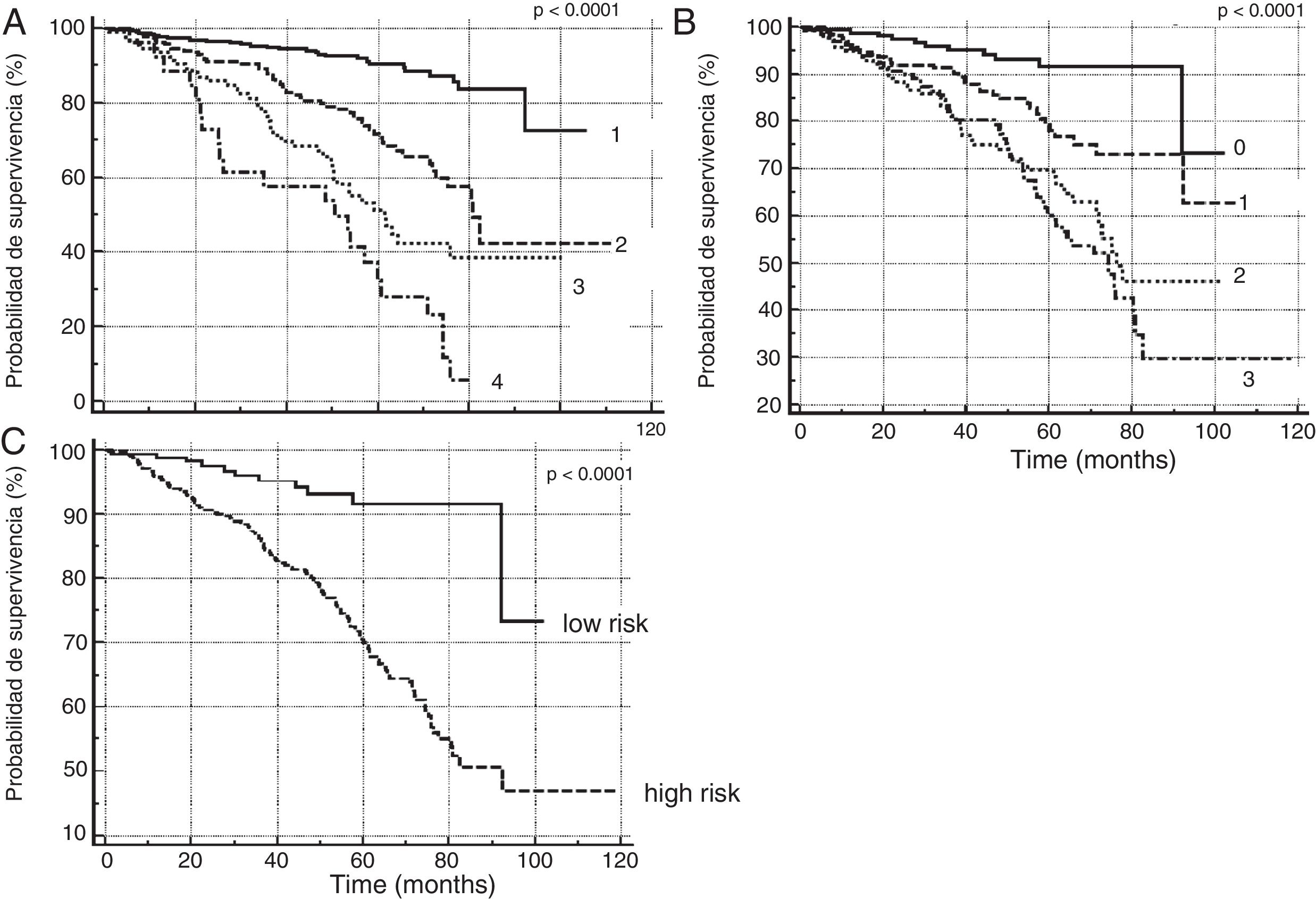

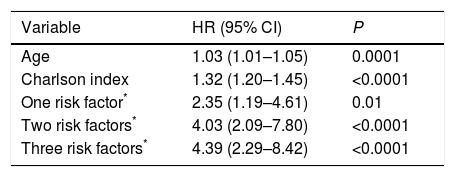

Fig. 1 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves for the three severity scales. In all cases, the different scores obtained from the scales allowed groups with different mortality risks to be identified (P<0.0001 for comparison of survival curves). Table 1 shows the results of the Cox analysis for the risk factor scale, which maintained its predictive value after correcting for potential confounding factors. The area under the ROC curve for classification by BODEx index quartiles (0.78, 95% CI: 0.75–0.81) was greater than the quantitative classification by risk factors (0.71, 95% CI: 0.68–0.75) (difference: 0.07, 95% CI: 0.03–0.09, P<0.0001).

Results of the Cox's proportional hazards multivariate analysis for the scale by number of GesEPOC 2017 risk factors, adjusted for age and comorbidity.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.0001 |

| Charlson index | 1.32 (1.20–1.45) | <0.0001 |

| One risk factor* | 2.35 (1.19–4.61) | 0.01 |

| Two risk factors* | 4.03 (2.09–7.80) | <0.0001 |

| Three risk factors* | 4.39 (2.29–8.42) | <0.0001 |

HR: hazard ratio.

Our study has limitations, and serves essentially to generate a hypothesis and stimulate scientific debate. Being a retrospective study, the risk of selection bias is obvious, as it was performed in a dedicated hospital clinic. Indeed, a very large number of patients were at high risk. Moreover, the study was not validated externally in an independent group. Nevertheless, the results suggest that a quantitative classification according to the number of risk factors present in each patient may have advantages over the dichotomous classification proposed by GesEPOC 2017, as subjects are classified according to escalating categories of risk of mortality that could guide intensification of treatment. This classification is more intuitive, and easy to apply in all areas of care, so it might achieve greater acceptance than the scale based on multidimensional severity indices. We must point out that there is no evidence to show that establishing several levels of risk could have therapeutic implications that translate to clinical outcomes. Our study also shows that classifying severity on the basis of multidimensional indices is more useful for predicting mortality, so such an approach is still recommendable in the settings in which it can realistically be applied. We report these results in the hope that they are of interest to specialists who manage COPD patients, although the potential application of the severity scale we propose, or of other alternatives, in decision-making would require an adequate external validation performed across the spectrum of disease severity.

Please cite this article as: Golpe R, Suárez-Valor M, Castro-Añón O, Pérez-de-Llano LA. Estratificación de riesgo de la enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica. ¿Se puede mejorar la propuesta de la guía española? Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:533–535.