Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is characterized by a triad of impaired in arterial oxygenation caused by intrapulmonary vascular dilatations (IPVD) in the setting of advanced liver disease.1 The most common respiratory symptom is progressive dyspnea.2,3 Platypnea-orthodeoxia (increased dyspnea and reduced oxygen saturation in an orthostatic position) can occur in up to 25% of patients.1 Other signs suggestive of HPS are telangiectasia, nail clubbing, and peripheral cyanosis.4 Echocardiography with agitated saline contrast is the method most widely used for detecting and confirming IPVD.1,3 Liver transplantation (LT) is the current treatment of choice, since medical options have not demonstrated effectiveness.5 HPS has been reported to coexist with other respiratory diseases that worsen gas exchange in up to 30% of cases.6 However, the association with diffuse interstitial pulmonary disease (ILD) has been rarely reported in the literature. HPS in a patient with ILD complicates the diagnostic process and may limit the treatment options for both entities.7–10 On the basis of these premises, we reviewed 3 cases of HPS coexisting with ILD, in order to describe the characteristics of clinical presentation and course (Table 1, Fig. 1).

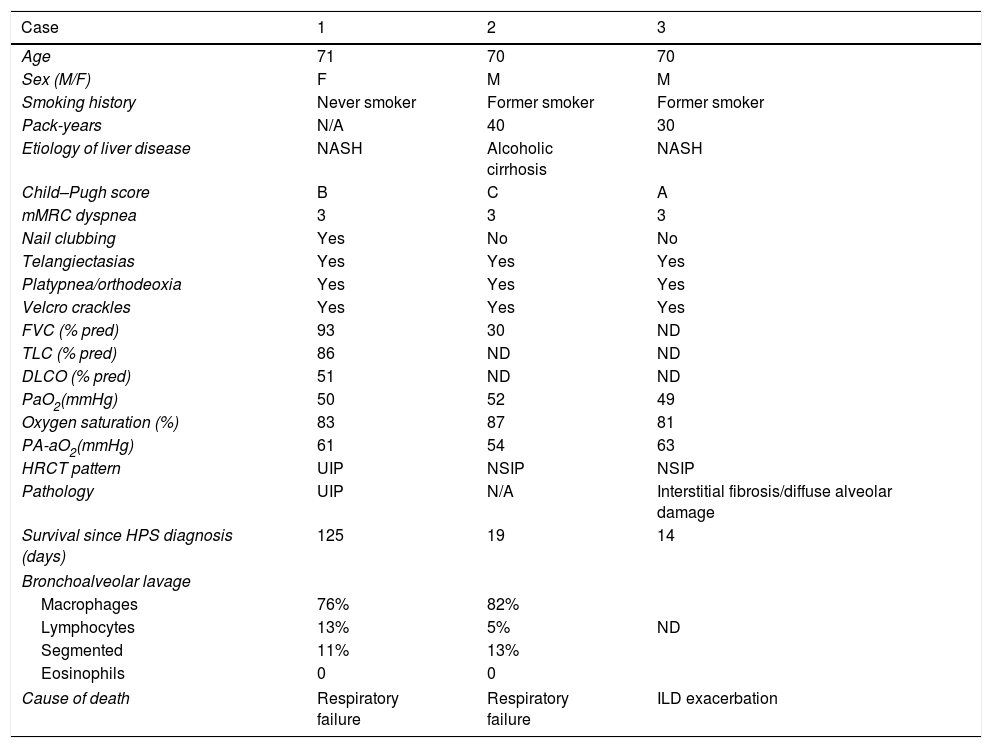

Clinical, functional, and radiological description of patients included in the series.

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 71 | 70 | 70 |

| Sex (M/F) | F | M | M |

| Smoking history | Never smoker | Former smoker | Former smoker |

| Pack-years | N/A | 40 | 30 |

| Etiology of liver disease | NASH | Alcoholic cirrhosis | NASH |

| Child–Pugh score | B | C | A |

| mMRC dyspnea | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Nail clubbing | Yes | No | No |

| Telangiectasias | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Platypnea/orthodeoxia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Velcro crackles | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FVC (% pred) | 93 | 30 | ND |

| TLC (% pred) | 86 | ND | ND |

| DLCO (% pred) | 51 | ND | ND |

| PaO2(mmHg) | 50 | 52 | 49 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 83 | 87 | 81 |

| PA-aO2(mmHg) | 61 | 54 | 63 |

| HRCT pattern | UIP | NSIP | NSIP |

| Pathology | UIP | N/A | Interstitial fibrosis/diffuse alveolar damage |

| Survival since HPS diagnosis (days) | 125 | 19 | 14 |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | |||

| Macrophages | 76% | 82% | |

| Lymphocytes | 13% | 5% | ND |

| Segmented | 11% | 13% | |

| Eosinophils | 0 | 0 | |

| Cause of death | Respiratory failure | Respiratory failure | ILD exacerbation |

Oxygenation changes as a diagnostic criterion of HPS were defined on the basis of the difference in basal alveolar and arterial oxygen (PA-aO2) (≥15mmHg in individuals under the age of 64 years and ≥20mmHg in patients older than 64 years).1

DLCO: alveolar diffusion of carbon monoxide; F: female; FVC: forced vital capacity; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; M: male; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council; N/A: Not applicable; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; ND: not done; PaO2: blood pressure of oxygen; TLC: total lung capacity.

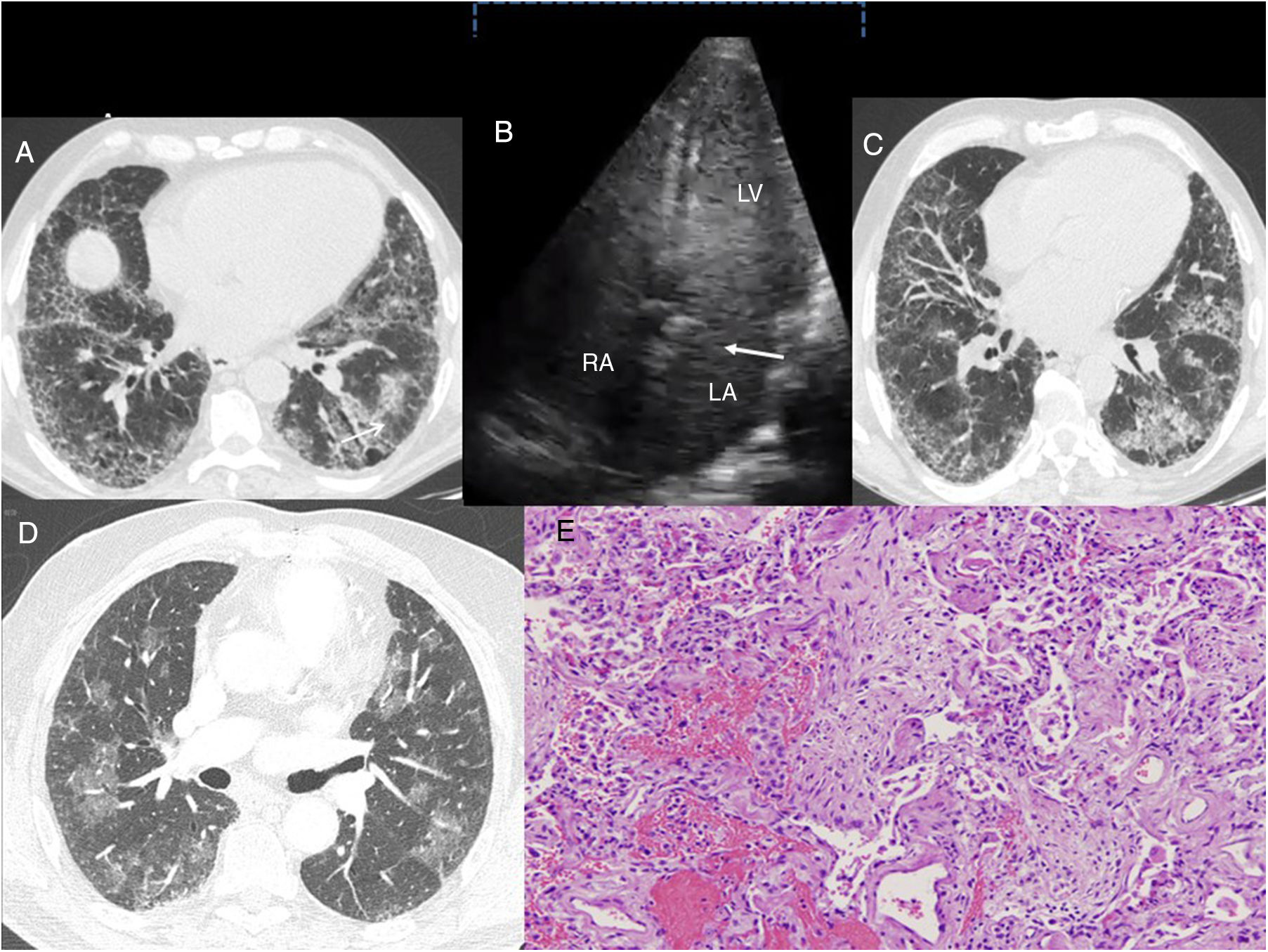

(A) Case 1: chest HRCT axial slice (lung window), showing reticular interstitial involvement, with septal thickening and ground-glass opacities in the lung bases and traction bronchiectasis (arrow). (B) Case 1: Echocardiogram with agitated saline contrast showing the late passage of bubbles to the left atrium after 3–6 beats (arrow). RA: right atrium; LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle. (C) Case 2: chest HRCT axial slice (lung window), showing subpleural reticulation with apex-base gradient, accompanied by distortion of the lung architecture and traction bronchiectasis. Areas of ground glass opacities with septal thickening are also observed. (D) Case 3: Chest HRCT axial slice (lung window) showing bilateral, patchy pulmonary ground glass opacities. E. Case 3. Histological image showing foci of bleeding with little reactive change in the alveolar epithelium. Inflammation and pneumocytic hyperplasia are also seen alternating with areas of lax fibrosis replacing the pulmonary parenchyma. These findings are compatible with acute alveolar damage (hematoxylin-eosin stain, 100×).

Case 1. A 71-year-old woman with no history of smoking or alcohol use, diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, confirmed by biopsy consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia in 2011. Increased liver enzymes were detected in a routine laboratory test, and the patient was referred to the gastroenterology department. A liver biopsy delivered a diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Three months after this diagnosis, the patient's dyspnea, hypoxemia, and carbon monoxide diffusion worsened. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) showed no progression in her fibrosis score and no decline was observed in forced vital capacity. After confirmation of the presence of HPS, the patient presented progressive clinical deterioration and died after 4 months.

Case 2. A 70-year-old man with a history of chronic alcohol use, diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis at the age of 65 years, admitted to the gastroenterology department due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. He reported a 3-month history of dyspnea on medium exertion. Chest X-ray showed radiological signs of ILD. HCRT showed a pattern of non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Given his respiratory failure, he was prescribed home oxygen therapy on discharge and completed follow-up as an outpatient. Autoimmunity and specific immunoglobulin G for avian antigens and fungi were negative. Lung biopsy could not be performed due to worsening of the patient's clinical situation and blood gases, and he was readmitted the following month. HPS was confirmed during this admission, and the patient's progress was poor, requiring high oxygen flows. He died 19 days later.

Case 3. A 70-year-old former smoker with no history of alcoholism, with suspected non-alcoholic steatohepatitis followed up in another hospital. He reported a 20-month history of dyspnea on minimal exertion, and a 2-year history of morning arthralgia in the hands and ankles. He also had a history of ischemic heart disease for which cardiological examinations had been performed, none of which showed any changes. He was admitted to the emergency department for worsening dyspnea and acute respiratory failure. A chest X-ray performed 11 months before admission showed a bilateral interstitial pattern. HRCT was performed, revealing a pattern suggestive of NSIP. Clinical laboratory tests were positive for antinuclear antibodies (1/320), anti-citrullinated cyclic peptide antibodies (46U/ml), and rheumatoid factor (46IU/ml). Symptoms progressed steadily, with severe hypoxemia requiring admission to the intermediate respiratory care unit, where echocardiogram was performed, confirming HPS. The patient died after 14 days, and the autopsy reported the presence of acute alveolar damage and cirrhosis of the liver.

These cases illustrate 3 different clinical scenarios in which the coexistence of HPS and ILD prompt several observations. Firstly, HPS can be a cause of disproportionate hypoxemia in ILD patients. In this setting, a greater reduction in carbon monoxide diffusion than expected might indicate an associated vascular problem or the presence of emphysema. As a result, this parameter may be less sensitive for evaluating ILD progress or response to specific treatment. Secondly, the presence of HPS can limit the diagnostic process of ILD, due to the risk involved in performing a lung biopsy in these patients. Moreover, if the patient has a previous diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (as in our first case), the available antifibrotic treatments would be contraindicated due to severe liver disease. Finally, ILD can worsen the prognosis of HPS, by limiting the access of these patients to LT. Risk of death in HPS patients is double that of patients with cirrhosis without HPS.1 For this reason, prompt inclusion in an LT program after diagnosis is recommended.1,4 Five-year survival after LT lies around 76%,2,11 while in patients who are not candidates for this procedure, mean survival is 24 months.2 The main causes of death in HPS are derived from the complications of the liver disease itself.6 As a result, the coexistence of the ILD may have resulted in the lower survival observed in our series compared to previous reports.

The pathogenesis of this association is unknown. However, fibrosing lung diseases and cirrhosis are characterized by the presence of epithelial/endothelial damage with abnormal scarring that leads to fibroproliferation and tissue remodeling,10 involving several common inflammatory cytokines and growth factors (TNF-α, IL-1, TGF-β and VEGF).2,6,10 A recent study pointed to telomere shortening as one of the possible mechanisms involved.12

In conclusion, the coexistence of HPS and ILD raises a number of difficulties in the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of both entities, and affects progress. Further studies are needed to explore the particularities of this association in order to be able to create strategies to improve prognosis.

The authors thank Dr J. L. Mate-Sanz for sharing and analyzing the histological images.

Please cite this article as: Rodriguez-Pons L, Prats M, Guasch-Arriaga I, Portillo K. Síndrome hepatopulmonar y enfermedad pulmonar intersticial difusa: una asociación poco conocida. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:582–584.