In recent years, we have seen the emergence of different methods of smoking tobacco and other substances that are increasing in popularity, mainly among young people and adolescents. Despite the messages propagated among the population, the safety of the fumes and smoke generated by these systems and their usefulness in smoking cessation have not been demonstrated.1

In this context, we present the case of a 33-year-old man, former smoker of 10 cigarettes/day from the age of 19 until 2 months previously, when he began to vape nicotine-free products (3 ml in 3 doses per day). He was receiving sertraline for an anxiety-depressive disorder, practiced sports regularly, and had no occupational risk exposure.

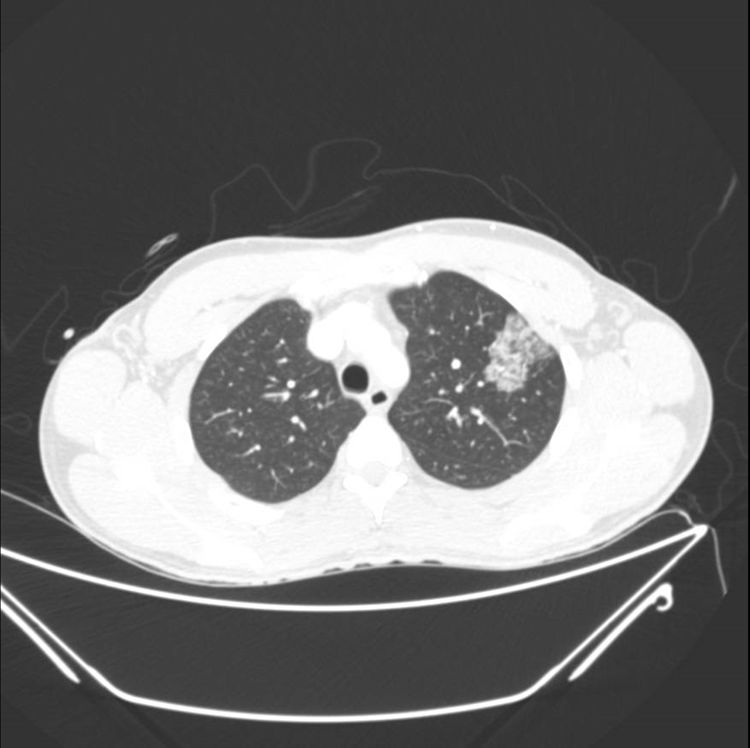

He presented in the emergency department with sudden onset of bloody expectoration after excessive consumption of vaping fluid (almost 30 ml, higher than usual) with a new flavoring agent. Upon arrival, the patient was hemodynamically stable, breathing normally, with a baseline oxygen saturation of 95%. Lab tests were performed, showing leukocytosis 12,230 cells/mm3. All other parameters were normal (platelets, coagulation, CRP, liver and renal profile, and later, autoimmune tests) and Ziehl staining in sputum was negative. Chest X-ray findings showed pathological changes. A CT scan was then performed, showing a ground glass infiltrate in the left upper lobe (Fig. 1). Under observation, the patient produced 40 ml bloody expectoration in 12 hours12 h, but after admission to the ward, he produced 50 ml in 1 h. An arteriography was performed, and a tortuous right bronchial artery was observed, which was embolized, reducing the bleeding. Despite this procedure, the patient continued to expectorate blood in smaller amounts, so a bronchoscopy was performed, showing active diffuse capillary bleeding in both sides, with no clear source, which could not be controlled with cold serum or adrenaline. He was then admitted to the ICU for monitoring and was treated with low-flow oxygen therapy through nasal prongs, antibiotics (levofloxacin), and corticosteroids (methylprednisolone). Fortunately, his progress was favorable; he did not require intubation and was moved to the ward within 48 h. When the patient was stable, bronchoscopy was performed, which ruled out any endobronchial lesion. Abundant siderophages were observed in bronchoalveolvar lavage, but no foamy macrophages were present and no microorganism was isolated. One month later, the patient was re-admitted to hospital-at-home, due to superinfection, for which he received another cycle of intravenous antibiotics. He subsequently remained asymptomatic until discharge from follow-up months later.

This is a case of special interest that can be added to the cases of lung damage associated with vaping, called e-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury (EVALI), that have recently been described. Nearly 3000 cases have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control in the United States, and the largest published cohort comprises 60 patients.2 For this reason, in September 2019, the Centers for Disease Control published a guide collating the available scientific evidence.

The diagnosis of a “confirmed” case is based on 4 criteria: 1) electronic cigarette use in the previous 90 days; 2) pulmonary opacities; 3) exclusion of lung infection (respiratory virus, influenza PCR, antigenuria for Legionella and Streptococcus pneumoniae: negative; blood cultures/sputum culture/bronchoalveolar lavage, detection of opportunistic germs, if performed: negative); and 4) no alternative diagnosis. A case would be designated as “probable” if no microbiological tests were carried out to rule out infection, or if any of these tests were positive but not considered clinically to be the only cause of the disease.3

Our patient is therefore a “probable” case of vaping-related lung disease, since the cause-effect relationship (use-hemoptysis) is very clear and only one sputum culture was available. Other causes of hemoptysis were ruled out by the laboratory tests: pulmonary-renal syndromes, bleeding disorders, and autoimmune diseases (normal labs), parenchymal lesions (infiltrate, tumors, cavities, bronchiectasis, etc., by CT scan), pulmonary thromboembolism, arteriovenous malformations, and endobronchial lesions (e.g., tumor or foreign body, by bronchoscopy).

It should be noted that no cases have been previously reported in Spain, and that our patient inhaled a flavoring substance that did not contain nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol or cannabidiol, as was the case for all patients previously published.2,4–6

The form of presentation with very acute hemoptysis after excessive consumption of the inhaled substance is also noteworthy, when compared with the mean 6-day duration of symptoms in other series (in the cohort of 53 patients). Hemoptysis is the least frequent of all symptoms presented (occurring in 11% of the series2,4). Different forms of presentation have been described: organizing pneumonia, lipoid pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, respiratory bronchiolitis, giant cell pneumonia,7 diffuse alveolar hemorrhage,8 and diffuse alveolar damage, among others.9–11

In terms of treatment, antibiotics covering the most common microorganisms in community-acquired pneumonia have been prescribed empirically in most patients. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended, except in life-threatening cases, in patients suffering from clinical deterioration and hypoxemia, and if eosinophilic or cryptogenic organizing pneumonia is observed, in line with standard care. The recommended treatment is methylprednisolone 0.5−1 mg/kg/day for 5−10 days, depending on the patient’s response and progress.4

With regard to disease course, series published so far (n = 534 and n = 602) report that more than half of the patients were admitted to the ICU, but less than one third required orotracheal intubation, and 3 deaths were recorded.2,4

In short, as professionals we must be alert to new patterns of inhaled drug use, because of our profound lack of knowledge of the short- and long-term effects. Cases like ours are beginning to reveal some of the consequences of short-term consumption, but the pathophysiological mechanism by which the lung injury occurs, the substances responsible for it, and its correct treatment are still unknown.

A patient registry, as proposed by SEPAR, is now urgently needed to enable us to carry out a thorough analysis of the cases and shed light on this new entity. We must establish more precise diagnostic criteria, identify the substances responsible for lung damage, and produce solid scientific evidence to guide the proper management of these patients and to convey a clear message to the general population and health authorities about these devices.

Please cite this article as: Cano Aguirre M d P, Esperanza Barrios A, Martínez Muñiz F, Alonso Viteri S, Muñiz González F, Segoviano Mateo R, et al. Hemoptisis secundaria a vapeo. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:505–506.