National health systems must ensure compliance with conditions such as equity, efficiency, quality, and transparency. Since it is the right of society to know the health outcomes of its healthcare system, our aim was to develop a proposal for the accreditation of respiratory medicine departments in terms of care, teaching, and research, measuring health outcomes using quality of care indicators. The management tools proposed in this article should be implemented to improve outcomes and help us achieve our objectives. Promoting accreditation can serve as a stimulus to improve clinical management and enable professionals to take on greater leadership roles and take action to improve outcomes in patient care.

Los sistemas nacionales de salud deben garantizar a los ciudadanos el cumplimiento de unas condiciones básicas como la equidad, la eficiencia, la calidad y la transparencia. En aras del derecho que tiene la sociedad a conocer los resultados de salud de su área sanitaria, el objetivo de este artículo es elaborar una propuesta de acreditación de los servicios de neumología desde el punto de vista asistencial, docente e investigador, midiendo sus resultados de salud a través de indicadores de calidad en la atención. Para mejorar estos, deberíamos utilizar unas herramientas de gestión (que se desarrollan en el artículo) y que, sin duda, nos ayudarían a conseguir los objetivos propuestos. La mejora del nivel de acreditación puede servir como estímulo para perfeccionar la gestión clínica y para que los profesionales ejerzan una capacidad de dirección cada vez mayor y adopten medidas para reforzar los resultados en la atención a sus pacientes.

National health systems must meet the basic needs of their citizens, including equity, efficiency, quality, and transparency1. As such, they must ensure universal access to quality medicine, regardless of economic level and social background; they must also resolve health problems at the appropriate level of care, avoiding medical interventions that do not improve health care processes. They must generate data on health activity and outcomes using indicators to identify dysfunctional areas2 and provide citizens access to this information. Health systems must integrate new technological resources, exploit information systems, promote networking at different levels of care, and ensure the clinical implementation of diagnostic and therapeutic advances3 in order to achieve maximum efficiency and the quality of care that they are obliged to provide.

The challenges facing health systems today mean that the health sector must be remodeled to improve quality and efficiency and boost sustainability4. If health outcomes are to be improved, strategies must be rethought, and processes for implementing and evaluating these strategies must advance. To address these challenges, respiratory medicine departments must be managed from a cross-sectional perspective; both inpatients and outpatients must be seen; chronic care must be guaranteed; different types of care processes must be coordinated; various care levels must be integrated; a plan for renewing and implementing technological resources must be in place; robust quality indicators must be developed; and teaching and research activities adapted to available resources must be implemented.

In Spain, the Quality of Care and Innovation Committee of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) is responsible for the accreditation of healthcare units, but that does not mean that the different departments meet the same quality standards. To date, evaluation of the quality of care, teaching and research in respiratory medicine departments has not been addressed, and the indicators that should be used for this purpose remain undefined.

In the context of the organizational changes demanded by the COVID-19 crisis, we propose a new respiratory medicine care circuit model for Spain, based on a strategy aimed at maximizing quality by using indicators that measure health, teaching, and research outcomes, thus giving the general access to information on the health outcomes achieved in their health area. To this end, tools (process mapping, care processes, scorecard, etc.) should be used to identify opportunities to improve clinical practice and decision-making in health management.

Current overview of health systems (how we want to be)To implement such a proposal, all professionals with management responsibilities should be trained and equipped to lead their respective teams and organizations5 toward the required transformation of the system. We believe that to achieve this goal, we need 1) a health outcomes-oriented system, 2) capacity to create value and 3) new procedures for measuring and evaluating cost and outcomes.

The focus on health outcomes is here to say, and these outcomes must be achieved at the least complex level of care, thus combining two elements that are often neglected: efficacy and sustainability. To achieve this, we must take into account two critical factors: the culture change required by decision-makers (politicians, managers, and health professionals), and the definition of a clear strategy that can be applied in this setting.

In the current context of health, economic and social crises, doing a good job no longer suffices: we must maximise quality given that achieving good health outcomes is the fundamental mission of any health system. The approach should therefore be to generate not more volume (“do more”), but more quality (“do better”)6, because this concept cannot be dissociated from patient interests.

Some of the barriers we face in the current model are a sub-optimal evaluative culture, due to the use of a model that is poorly adapted to measuring outcomes, and a lack of coordination and clinical integration between levels. We must therefore be able to incorporate a system that facilitates the documentation and analysis of the outcomes of our departments in order to obtain data on success and costs. Follow-up would also help adapt care processes, improve the quality of care and reduce expenditure, as has already been observed in several areas of respiratory medicine7–10.

Management toolsOne of the keys to the accreditation of respiratory medicine departments11 would be to determine health outcomes using pre-established quality-of-care indicators. To improve these outcomes, we must apply management tools that can help us achieve our goals.

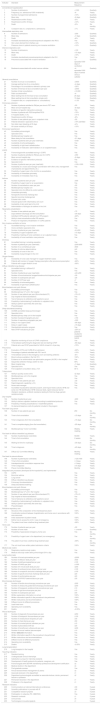

Process mapping Process mapping is the graphical representation of the procedures implemented by a given organization12 (in this case, a respiratory medicine department). It consists of a diagram that contains strategic lines and care, operational and support processes; it provides a global view of the department and positions each factor in the value chain. This diagram should summarize all the processes and subprocesses of the department and how they interrelate (Fig. 1).

Process mapping of a respiratory medicine department.

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR: human resources; ICU: intensive care unit; ILD: interstitial lung disease; IT: information technology; OC: outpatient clinics; PC: primary care; PE: pulmonary embolism; SERGAS: Galician Health Service.

Strategic lines highlight the organization’s relationship with its setting and how decisions on planning and institutional improvements are made. They are often established by management and show how the organization operates and creates value for the patient and the healthcare system. They establish the general guidelines, directives, and intervention levels for each department. Each department must integrate its strategic plan with those of general management and the health system. Operational processes are directly linked to the delivery of services to the patient. Finally, support processes, despite not being directly linked to meeting user needs, are those that complement the operational mechanisms; without them, it would be impossible to achieve objectives. This includes, for example, IT support for all departments.

Healthcare processes Care processes systematically define how clinical practice should be, based on available scientific evidence. They integrate the care that is received at different levels and facilitate coordination among professionals, improving the continuity of care, and offering the patient integral care. These processes, therefore, help define care circuits by enabling access to health resources and avoiding delays in diagnostic confirmation or treatment13,14.

In a respiratory medicine department there are at least 6 healthcare processes that we could define as priority, given their high prevalence or their high impact or complexity: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchial asthma, lung cancer, diffuse interstitial lung disease (ILD), pulmonary embolism (PE), and sleep-disordered breathing. The aim of the care processes in these diseases would be reach a consensus in clinical practice to decrease clinical variability, to ensure continuity of care between levels, to improve control and health-related quality of life, to achieve early diagnoses with easy access to diagnostic techniques, to ensure early treatment and improve adherence, to reduce exacerbations, and to promote health education for patients and caregivers.

Fast track Fast-track care was developed by adapting certain documents used in quality management in industry (standard working procedures)15 in order to maximise the use of resources by completing tasks within a set time. A fast track can be defined as an outpatient care plan that is suitable for a group of patients with a certain disease and a predictable clinical course. Implementing this strategy reduces time of care and diagnosis, but does not necessarily lead to an improvement in survival, as observed in lung cancer16.

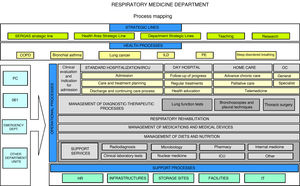

Its objectives are to reduce variability in clinical practice, assign responsibilities, provide legal support to professionals, speed up the organization’s registration processes, promote clinical research, improve quality of care, especially with regard to “adverse events” and “complications”, and adapt the available resources to the prevailing needs. A clinical pathway must be designed and developed according to certain criteria: the diseases treated must be common within the department/hospital, clearly defined, and must follow a predictable, largely consistent clinical course that allows for standardized care; it must be possible to reach a professional consensus in the department/hospital to help implement a multidisciplinary approach to the diseases; and the diseases must represent a significant risk to the patient and a significant cost to the institution. In our department, three fast tracks have been implemented: lung cancer, ILD (Fig. 2) and pleural effusions.

Fast track model for diffuse interstitial lung diseases.

CHUS: University Hospital Complex of Santiago; EBUS: endobronchial ultrasonography; ECG: electrocardiogram; FB: fiberoptic bronchoscopy; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; ILD: diffuse interstitial lung disease; LFT: lung function tests; PA: pathological anatomy; RDL: radiology; Rheu: rheumatology; RM: respiratory medicine; Rx: radiography; ThS: thoracic surgery; VATS: video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

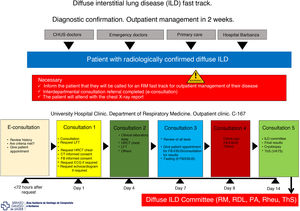

Remote visits Moving some processes to outpatient care (fast tracks), as well as the use of certain resources to reduce the number of admissions (one-stop clinics, day hospital, etc.), has led to a progressive increase in the number of respiratory medicine outpatient visits. This has led to the launch of remote consultations (e-consultation) in some hospitals, in which primary care physicians, after recording all relevant clinical information, seek advice from the pulmonologist17. The latter decides which patients might benefit from hospital care and which ones should continue in primary care, and specifies the action to be taken. The outcomes of this system have been excellent.18

E-consultations provide a number of benefits to patients (reduced waiting time compared to the traditional pathway; more agile care; prioritization of waiting times based on defined clinical criteria; access to specialist opinion while avoiding travel to other centers; simple procedures in case of referral; care delivered at the patients’ own health center; availability of a legible written report; primary care and hospital physicians working with the patient’s medical history and using the same clinical guidelines). Physicians also benefit, whether they work in primary care (receiving hospital reports with advice on follow-up and indications whether referral is required; fluid communication; training and continuing professional development), or in the hospital (receiving requests that include patient history, current episode, diagnosis, treatment, and reason for inter-departmental consultation according to the criteria of the clinical guidelines; access to laboratory results and reports; fluid communication via a data system with secure access and transmission). Fig. 3 shows the referral procedure from primary care to respiratory medicine in our hospital. The pulmonologist responds in less than three days. The estimate is that approximately 40% of patients will be able to continue in primary care, and the rest should be seen in the respiratory medicine department within a maximum of 3 weeks, after performing the basic tests (chest X-ray, spirometry or respiratory polygraphy) as required.

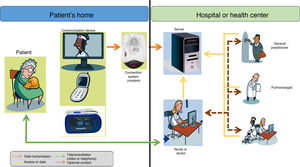

Telemedicine One of the priority objectives in the treatment of patients with chronic respiratory conditions and advanced neuromuscular diseases, in addition to improving quality of life and life expectancy with the increasingly generalized use of ventilatory support19, is to try to maintain stability and avoid exacerbations. This is to avoid the increased risk of death in these situations and to reduce emergency visits, prevent readmissions20, decrease the demand for hospital beds for acute patients21, and reduce the cost of care.

In chronic diseases, it is very important to determine the health status of patients and to anticipate possible episodes of exacerbation of their underlying disease. Telemonitoring at home could undoubtedly help in this area (Fig. 4). So far, most experience is available in COPD, probably because it is both a chronic and a highly prevalent condition. The results of home telemonitoring in COPD patients are good, but exceptions have been reported. Some studies showed fewer hospital admissions and lower mortality during a 1-year follow-up22, a decrease in mortality or readmission rate at 12 months23, and a reduction in hospitalization rates and emergency visits, although no effect on mortality was observed24. However, other authors found no significant differences in these variables25.

Balanced scorecard The balanced scorecard is a document containing a set of previously established indicators that provide information on the attainment of the proposed objectives and targets - information that can also permit comparison with results obtained by other departments26. The application of this tool can serve as a stimulus to improve clinical management and encourage managers to use all kinds of resources to improve patient care27,28. This information can enable professionals to take on increasing leadership responsibilities and to take steps to improve outcomes in patient care29.

Proposal for the control of care qualityMeasuring the quality of health care is, in our view, one of the best methods of implementing a protective health policy. What is not measured does not exist and therefore cannot be improved. We must therefore select indicators that, when regularly measured, help determine the quality and efficiency of our care activity, identify the opportunities for improvement in our departments, and compare our outcomes with those of the reference centers in our specialty. These indicators can also highlight any significant differences relative to the outcomes obtained in other areas, even those that have the same resources, allowing managers to immediately remedy shortcomings and identify unjustified duplication of tasks, and compelling us to implement integrated healthcare networks.

We propose below a series of indicators that will reflect the efficiency of our systems and, based on health outcomes obtained, will lead to the accreditation of respiratory medicine departments. Our proposal aims merely to stimulate reflection and discussion, and it must be the SEPAR Quality of Care and Innovation Committee, guided by external experts in the organization, evaluation, and audit of clinical management, who have the last word in selecting the indicators that best assess the quality of the healthcare provided within each health area.

Table 1 shows the proposed indicators, in absolute numbers and measurement intervals. It is intended for tertiary hospitals, but a more appropriate approach may be to express the numbers by proportions adapted to each organization to avoid placing departments with a smaller volume of patients at a disadvantage. We leave the final selection to the evaluation committee, who must also determine accreditation levels (e.g., 1, 2, and 3) based on the degree of compliance with the set of indicators agreed upon by the authors of this article and grouped according to the different care areas of a respiratory medicine department.

Proposed quality indicators for a respiratory medicine department.

| Indicator | Standard | Measurement frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional hospitalization | |||

| 1 | Number of admissions | >1300 | Quarterly |

| 2 | Frequency (no. admissions/1000 inhabitants) | <6 | Yearly |

| 3 | Number of programmed admissions | <10% | Quarterly |

| 4 | Mean stay | <9 days | Quarterly |

| 5 | Readmissions within 8 days | <5% | Yearly |

| 6 | Readmissions within 30 days | <10% | Yearly |

| 7 | Death | <5% | Six monthly |

| 8 | Complaint rate (no. complaints/no. admissions) | <1% | Yearly |

| Intermediate respiratory care | |||

| 9 | Number of admissions | >200 | Quarterly |

| 10 | Mean stay | <7 days | Quarterly |

| 11 | Death | <8% | Yearly |

| 12 | Available standardized procedures/protocols adapted to the IRCU | Yes | Yearly |

| 13 | Skin ulcers derived from interface use | <10% | Quarterly |

| 14 | Pressure ulcers in patients receiving non-invasive ventilation | <10% | Quarterly |

| Intensive respiratory care | |||

| 15 | Number of admissions | >100 | Yearly |

| 16 | Mean stay | <10 days | Yearly |

| 17 | Death | <10% | Yearly |

| 18 | Available standardized procedures/protocols adapted to the ICU | Yes | Yearly |

| 19 | Pneumonia associated with invasive ventilation | <7 episodes/1000 days of ventilation | Quarterly |

| 20 | Bacteremia associated with central venous catheter | <4 episodes/1000 days of central venous catheter | Quarterly |

| General consultations | |||

| 21 | Number of annual e-consultations | >3500 | Quarterly |

| 22 | Average waiting time for e-consultation | <4 days | Quarterly |

| 23 | Percentage of e-consultations referred to primary care | <30% | Quarterly |

| 24 | Number of first face-to-face consultations per year | >2000 | Quarterly |

| 25 | Number of total consultations | >10,000 | Quarterly |

| 26 | Ratio successive/first | <4 | Quarterly |

| 27 | Mean waiting time for first face-to-face consultation | 25 days | Quarterly |

| 28 | Mean waiting time to first consultation (single visit) | 15 days | Quarterly |

| 29 | Complaint rate (no. complaints/total no. consultations) | <1.5% | Yearly |

| Pulmonary embolism | |||

| 30 | Number of patients admitted to RM per year due to PET scan | >50 | Yearly |

| 31 | Mean annual hospital stay | <8 days | Yearly |

| 32 | Existence of specific intervention protocols | Yes | Yearly |

| 33 | Number of patients with PESI/simplified PESI | <75% | Yearly |

| 34 | In-hospital deaths; n (%) | <10 % | Yearly |

| 35 | Readmissions within 30 days | <8% | Yearly |

| 36 | Number of new patients per year in outpatient visits | >50 | Yearly |

| 37 | Patients followed in specialist clinics | >75% admitted | Yearly |

| 38 | Non-fatal major bleeding at 30 days | <4% | Yearly |

| 39 | All-cause mortality at 30 days | <10% | Yearly |

| Pulmonary hypertension | |||

| 40 | Accredited pulmonologist | Yes | Yearly |

| 41 | Specialist clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 42 | Multidisciplinary hospital unit | Yes | Yearly |

| 43 | Mean delay for first consultation | <21 days | Yearly |

| 44 | Number of patients seen per year (new/total) | 10/50 | Yearly |

| 45 | Availability of echocardiography | Yes | Yearly |

| 46 | Availability of right heart catheterization | Yes | Yearly |

| 47 | Availability of medication administration on an outpatient basis | Yes | Yearly |

| COPD | |||

| 48 | Pulmonologist with accredited training in COPD | Yes | Yearly |

| 49 | Number of patients admitted to RM per year for COPD | >350 | Yearly |

| 50 | Mean annual hospital stay | <9 days | Yearly |

| 51 | Existence of specific intervention protocols | Yes | Yearly |

| 52 | Specialist clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 53 | Number of patients seen per year (new/total) | >100/>1000 | Yearly |

| 54 | Availability of a nurse case manager (coordination with other units, management of procedures and appointments, etc.) | Yes | Yearly |

| 55 | Possibility of urgent care in the Unit for an exacerbation | Yes | Yearly |

| 56 | Availability of immediate spirometry | Yes | Yearly |

| 57 | Availability of immediate chest X-ray | Yes | Yearly |

| Asthma | |||

| 58 | Number of patients seen per year | >500 | Yearly |

| 59 | Possibility of urgent care for an exacerbation | Yes | Yearly |

| 60 | Number of exacerbations seen per year | >50 | Yearly |

| 61 | Multidisciplinary hospital unit | Yes | Yearly |

| 62 | Specialist clinic for difficult-to-control asthma | Yes | Yearly |

| 63 | Immediate spirometry | Yes | Yearly |

| 64 | Nonspecific bronchial challenge test | Yes | Yearly |

| 65 | Specific bronchial challenge test | Yes | Yearly |

| 66 | Exhaled nitric oxide | Yes | Yearly |

| 67 | Induced sputum with inflammatory cell count | Yes | Yearly |

| 68 | Availability of skin prick test in the Unit | Yes | Yearly |

| 69 | Administration of biologics for asthma in the Unit | Yes | Yearly |

| Respiratory rehabilitation | |||

| 70 | Number of new patients per year | >75 | Yearly |

| 71 | Days between discharge and first consultation | <30 days | Yearly |

| 72 | Admitted COPD patients referred to an RR program | >80% | Yearly |

| 73 | Ability to treat exacerbations after RR session | Yes | Yearly |

| 74 | Protocol for respiratory rehabilitation in COPD patients | Yes | Yearly |

| Non-invasive ventilation at home | |||

| 75 | Accredited training in non-invasive ventilation | Yes | Yearly |

| 76 | Home ventilation specialist clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 77 | Number of patients per year (new/total) | >0/>200 | Yearly |

| 78 | Possibility of urgent outpatient care | <15 days | Yearly |

| 79 | Possibility of starting of home ventilation on an outpatient basis | Yes | Yearly |

| 80 | Availability of home ventilation care protocols | Yes | Yearly |

| Smoking | |||

| 81 | Accredited training in smoking cessation | Yes | Yearly |

| 82 | Number of patients per year (new/total) | ≥200/≥600 | Yearly |

| 83 | Number of co-oximetries per year | ≥600 | Yearly |

| 84 | Number of cotinine determinations | ≥40 | Yearly |

| 85 | Availability of nurse in the Unit | Yes | Yearly |

| 86 | Availability of psychologist in the Unit | Yes | Yearly |

| Oxygen therapy | |||

| 87 | Availability of nurse case manager for oxygen treatment cases | Yes | Yearly |

| 88 | Patients with revision of oxygen therapy prescription after provisional prescription | >80% | Yearly |

| 89 | Patients with oxygen titration at rest | >90% | Yearly |

| Diffuse interstitial lung disease | |||

| 90 | Accredited training in diffuse ILD | Yes | Yearly |

| 91 | Specialist clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 92 | Number of patients per year (new/total) | >40/>200 | Yearly |

| 93 | Number of bronchoalveolar lavages/transbronchial biopsies per year | >30 | Yearly |

| 94 | Number of cryobiopsies per year | >25 | Yearly |

| 95 | Number of VATS per year | >7 | Yearly |

| 96 | Availability of echocardiography | Yes | Yearly |

| 97 | Availability of right heart catheterization | Yes | Yearly |

| Bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis | |||

| 98 | Accredited pulmonologist | Yes | Yearly |

| 99 | Multidisciplinary CF unit in the hospital | Yes | Yearly |

| 100 | Number of new patients per year (Bronchiectasis/CF) | >75/>10 | Yearly |

| 101 | Day hospital to treat exacerbations | Yes | Yearly |

| 102 | Test of tolerance to antibiotics and hypertonic serum | Yes | Yearly |

| 103 | Possibility of administering IV antibiotics in outpatient clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 104 | Ability to perform spirometry the same day | Yes | Yearly |

| 105 | Physiotherapist | Yes | Yearly |

| Sleep-disordered breathing | |||

| 106 | CEAMS-accredited sleep pulmonologist | Yes | Yearly |

| 107 | Specialist clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 108 | Multidisciplinary sleep unit in the hospital | Yes | Yearly |

| 109 | Number of polysomnographs per year | >150 | Yearly |

| 110 | Number of respiratory polygraphs per year | >300 | Yearly |

| 111 | Delay in non-urgent cases | <90 days | Yearly |

| 112 | Delay in urgent cases | <15 days | Yearly |

| 113 | Standardized education program | Yes | Yearly |

| 114 | New CPAP indications per year | >25% of patients studied for suspected SAHS | Yearly |

| 115 | Objective monitoring of hours of CPAP compliance | Yes | Yearly |

| 116 | Time between performing the diagnostic test and starting CPAP | <60 days | Yearly |

| 117 | Patients who use CPAP prescribed for SAHS at least 4 h of per day | >70% | Yearly |

| Pneumonia | |||

| 118 | Evaluation of PSI and CURB-65 on admission | >90% | Yearly |

| 119 | Percentage of patients admitted with PSI I and II. | <10% | Yearly |

| 120 | Time between arrival in the emergency room and starting antibiotic | <8 h | Yearly |

| 121 | Blood cultures available in the first 72 h | 100% | Yearly |

| 122 | Existence of an antimicrobial use optimization program (AUOP) in the hospital | Yes | Yearly |

| 123 | Sequential antibiotic therapy (switch to oral) | 90% | Yearly |

| 124 | Mean hospital stay | <7 days | Quarterly |

| 125 | Specialist clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 126 | First outpatient consultation delay <72 h | 90 % | Yearly |

| Tuberculosis | |||

| 127 | Ability to quickly access clinic | ≤2 days | Yearly |

| 128 | Multidisciplinary unit in the hospital | Yes | Yearly |

| 129 | Specialist clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 130 | Number of new patients per year | >30 | Yearly |

| 131 | Rapid diagnostic capability (<3 h) | Yes | Yearly |

| 132 | Nurse case manager | Yes | Yearly |

| 133 | Accredited mycobacteria laboratory (bacilli, solid-liquid media cultures, MTB and some non-TB identification, MTB molecular tests, rapid molecular test for rifampicin resistance, antibiotic resistance testing for first-line drugs, genetic resistance tests) | Yes | Yearly |

| Day hospital | |||

| 134 | Number of patients per year | >800 | Yearly |

| 135 | Ability to deliver outpatient treatment according to established protocols | Yes | Yearly |

| 136 | Possibility of treating exacerbations in readmitted patients | Yes | Yearly |

| 137 | On-demand telephone visits for patients included in the program | ||

| Fast track lung cancer | |||

| 138 | Number of new patients per year | 250 | Six monthly |

| 139 | Time to first consultation | <15 days | Six monthly |

| 140 | Time to diagnosis (from first consultation) | <15 days | Six monthly |

| 141 | Time to complete staging (from first consultation) | <25 days | Six monthly |

| 142 | Multidisciplinary Tumor Committee | Weekly meeting | Yearly |

| Fast track for diffuse interstitial lung disease | |||

| 143 | Number of patients/year (new/total) | 50/200 | Yearly |

| 144 | Time to first consultation | 2 weeks | Six monthly |

| 145 | Waiting list time for cryobiopsy | <30 days | Six monthly |

| 146 | Time to diagnosis | <45 days | Six monthly |

| 147 | Diffuse ILD Committee Meeting | Monthly meeting | Yearly |

| Fast track for pleural effusion | |||

| 148 | Number of patients/year (new/total) | >125/>400 | Yearly |

| 149 | Time to first consultation | ≤ 3 days | Yearly |

| 150 | Interdepartmental consultation response time | ≤ 2 days | Yearly |

| 151 | Time to diagnosis | ≤15 days | Yearly |

| 152 | Pleura Committee Meeting | Monthly | Yearly |

| Integrated care processes (developed at the hospital/AC) and implemented | |||

| 153 | COPD | Yes | Yearly |

| 154 | Bronchial asthma | Yes | Yearly |

| 155 | Lung cancer | Yes | Yearly |

| 156 | Diffuse interstitial lung disease | Yes | Yearly |

| 157 | Pulmonary thromboembolism | Yes | Yearly |

| 158 | Sleep-disordered breathing | Yes | Yearly |

| Bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis | |||

| 159 | Accredited pulmonologist | Yes | Yearly |

| 160 | Multidisciplinary CF unit in the hospital | Yes | Yearly |

| 161 | Number of new patients per year (Bronchiectasis/CF) | >75/>10 | Yearly |

| 162 | Day hospital to treat exacerbations | Yes | Yearly |

| 163 | Test of tolerance to antibiotics and hypertonic serum | Yes | Yearly |

| 164 | Possibility of administering IV antibiotics in outpatient clinic | Yes | Yearly |

| 165 | Ability to perform spirometry the same day | Yes | Yearly |

| 166 | Physiotherapist | Yes | Yearly |

| Palliative respiratory care | |||

| 167 | Structure of the composition of the interdisciplinary team | 100% | Yearly |

| 168 | Coordination protocol between hospitalization and home care in accordance with area resources | 100% | Yearly |

| 169 | Initial assessment of patient needs | 100% | Yearly |

| 170 | Define how to access the Unit in case of emergency | 100% | Yearly |

| 171 | The patient must have a defined drug treatment plan | >90% | Yearly |

| Home care | |||

| 172 | Number of patients seen per year | >50 | Yearly |

| 173 | Number of home visits | 1 a month | Quarterly |

| 174 | Possibility of specialized emergency home care | Yes | Six monthly |

| 175 | Possibility of urgent care in the department (non-emergency) | Yes | Six monthly |

| 176 | The patient must have a defined drug treatment plan | >90% | Six monthly |

| 177 | The unit must have written patient admission criteria | 100% | Yearly |

| Medical duty rosters | |||

| 178 | Respiratory medicine duty rosters | Yes | Yearly |

| 179 | Medical area duty rosters with pulmonologist 24 h a day | Yes | Yearly |

| Lung function tests | |||

| 180 | Number of forced spirometries per year | ≥2000 | Yearly |

| 181 | Number of diffusion tests per year | ≥500 | Yearly |

| 182 | Number of plethysomographies per year | ≥100 | Yearly |

| 183 | Number of FeNOs per year | ≥1000 | Yearly |

| 184 | Number of 6-minute walk tests per year | ≥200 | Yearly |

| 185 | Number of cardiopulmonary stress tests per year | ≥100 | Yearly |

| 186 | Number of nonspecific bronchial challenge tests per year | ≥100 | Yearly |

| 187 | Number of specific bronchial challenge tests per year | ≥20 | Yearly |

| 188 | Number of oscillometries per year | ≥20 | Yearly |

| 189 | Number of PIP/PEP determinations per year | ≥30 | Yearly |

| Bronchoscopy techniques | |||

| 190 | Number of flexible bronchoscopy procedures per year | ≥500 | Yearly |

| 191 | Number of ultrasound-guided bronchoscopy procedures per year | ≥200 | Yearly |

| 192 | Number of therapeutic endobronchial procedures per year | ≥10 | Yearly |

| 193 | Number of rigid bronchoscopies per year | ≥10 | Yearly |

| 194 | Number of cryobiopsies per year | ≥30 | Yearly |

| 195 | Written explanatory information on arrival | 100% | Yearly |

| 196 | Written information specific to the procedure to be performed | 100% | Yearly |

| 197 | Written instructions and recommendations | 100% | Yearly |

| 198 | Different rooms for different procedures | Yes | Yearly |

| 199 | Lead-lined room | Yes | Yearly |

| 200 | Operating room availability | Yes | Yearly |

| 201 | Deaths | <0.05% | Yearly |

| Pleural techniques | |||

| 202 | Number of diagnostic thoracenteses per year | ≥250 | Yearly |

| 203 | Number of therapeutic thoracenteses per year | ≥100 | Yearly |

| 204 | Number of closed pleural biopsies per year | ≥30 | Yearly |

| 205 | Number of chest drains per year | ≥50 | Yearly |

| 206 | Number of tunneled pleural catheters per year | ≥15 | Yearly |

| 207 | Number of pleurodesis with talc | ≥20 | Yearly |

| 208 | Number of transthoracic ultrasounds per year | ≥400 | Yearly |

| 209 | Number of annual medical pleuroscopies | ≥10 | Yearly |

| 210 | Written welcome information | Yes | Yearly |

| 211 | Written information specific to the procedure to be performed | Yes | Yearly |

| 212 | Written instructions and recommendations | Yes | Yearly |

| 213 | Different rooms for different procedures | Yes | Yearly |

| 214 | Operating room availability | Yes | Yearly |

| 215 | Deaths | <0.05% | Yearly |

| Lung transplantation | |||

| 216 | Lung transplant in the hospital | Yes | Yearly |

| Teaching indicators | |||

| 217 | Resident training | Yes | Yearly |

| 218 | Undergraduate clinical internships | Yes | Yearly |

| 219 | Satisfaction surveys for internship students | Yes | Yearly |

| 220 | Development of health protocols for patients, caregivers, etc. | Yes | Yearly |

| 221 | Pulmonologists with SEPAR membership-professional development certification | ≥2 | Yearly |

| 222 | Medical doctors in the department | ≥4 | Yearly |

| 223 | Post-graduate courses | Yes | Yearly |

| 224 | Annual doctoral thesis management (5 years) | ≥2 | Yearly |

| 225 | Associate lecturers in the department | ≥1 | Yearly |

| 226 | Department pulmonologists accredited as associate lecturer, doctor, permanent lecturer or professor | ≥2 | Yearly |

| 227 | Permanent lecturers in the department | ≥1 | Yearly |

| 228 | Professors in the department | ≥1 | Yearly |

| Research indicators | |||

| 229 | Communications at national/international conferences | ≥30 | 5 years |

| 230 | Scientific publications in journals with IF | ≥30 | 5 years |

| 231 | Competitive research projects | ≥3 | 5 years |

| 232 | Participation in networks (PII, CIBERES) | Yes | 5 years |

| 233 | Research contracts | ≥1 | 5 years |

| 234 | Clinical trials | ≥5 | 5 years |

| 235 | Technological innovation/patents | ≥1 | 5 years |

AC: autonomous community; CEAMS: Spanish Committee for Accreditation of Sleep Medicine; CF: cystic fibrosis; CIBERES: biomedical research network in respiratory diseases; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; CURB-65: confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure and age (>65 years); FeNO: exhaled fraction of nitric oxide; IF: impact factor; ICU: intensive care unit; ILD: interstitial lung disease; IRCU: intermediate respiratory care unit; MTB: Mycobacterium tuberculosis; PE: pulmonary embolism; PESI: Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index; PIP/PEP: Peak inspiratory and expiratory pressure; PSI: Pneumonia Severity Index; RM: respiratory medicine; RR: respiratory rehabilitation; SAHS: sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome; SEPAR: Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery; TB: tuberculosis; VATS: video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Respiratory medicine departments should also be evaluated from a teaching perspective, since, under the provisions of article 104 of the General Health Law, “the entire healthcare structure of the health system must be at the disposal of undergraduate and post-graduate teaching and continuing professional development”.

The areas that the authors of this article believe should be evaluated include the participation of respiratory medicine departments in the training of medical students; teaching clinical internships throughout different courses (undergraduate teaching); National Commission of Teaching accreditation of the training of specialists in respiratory medicine (postgraduate teaching); the number of annual doctoral theses directed (continuing training); and the number of associate lecturers, permanent lecturers and professors in each department. This, of course, is a proposal and, as mentioned above, it must be SEPAR and the evaluation committee who decide on the criteria to be included. In this regard, the European HERMES initiative seeks to ensure that all respiratory medicine training networks have the opportunity to obtain accredited certification for their educational programs30.

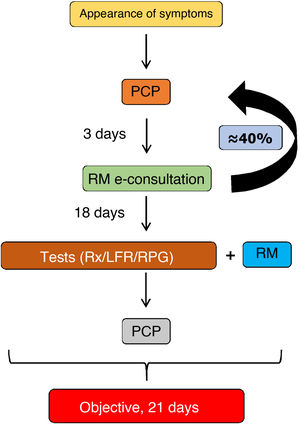

ResearchResearch in a respiratory medicine department must be recognized as an essential part of professional development, as it clearly contributes to improving the quality of care provided not only by the pulmonologist, but also the department and the hospital. This is because research generates new knowledge, promotes continuing training and professional stimulus, can attract new economic resources, and contributes to improving the image of the institution and, consequently, to the pride of belonging to a prestigious center31. To perform research, we pulmonologists should subscribe to networking structures, such as SEPAR projects or the CIBER centers for biomedical research for respiratory diseases of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. It is also important for hospitals to have the backing of a health research foundation, ideally with university support, that promotes research, and for the different research units of the hospital, health institutions and university to coordinate their efforts and encourage research careers. Furthermore, foundations can work together to improve their competitive edge when bidding for publicly funded research grants, and to reduce the cost of projects by making their structure or their own funds available to researchers and by making the necessary investments (Fig. 5).

Research in a respiratory medicine department supported by the hospital, university, foundation, research consortium (Campus Vida) and networking structures (CIBERES and PIIs).

Fidis: Health Research Foundation Institute of Santiago de Compostela; USC: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela.

Society’s demand for high-quality health services and the right to know the health outcomes of its health area will continue to grow. All departments will be required to objectively demonstrate their competences, and, as such, will most likely have to be globally accredited. At present, one of the weaknesses of the health system is its failure to monitor existing indicators, thus generating unacceptable variability in our clinical practice. The demands of society may prompt the health system to respond to the need to measure outcomes using quality-of-care indicators, improve clinical management, and encourage professionals to strengthen their leadership roles.

FundingThis paper has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Álvarez- Dobaño JM, Atienza G, Zamarrón C, Toubes ME, Ferreiro L, Riveiro V, et al. Resultados de salud: hacia la acreditación de los servicios de neumología. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:637–647.