To assess the relationship between the parameters obtained in the geriatric assessment and mortality in elderly people with community-acquired pneumonia in an acute care geriatric unit.

MethodsFour hundred fifty-six patients (≥75years). Variables: age, sex, referral source, background, consciousness level, heart rate, breathing rate, blood pressure, laboratory data, pleural effusion, multilobar infiltrates, functional status (activities of daily living) prior to admission [Lawton index (LI), Barthel index (BIp)] prior to and at admission (BIa), cognitive status [Pfeiffer test (PT)], comorbidity [Charlson index (ChI)] and nutrition (total protein, albumin).

ResultsA hundred ten patients died (24.2%) during hospitalization. These patients were older (86.6±6.4 vs 85.1±6.4, P<.04), had more comorbidity (ChI 2.35±1.61 vs 2.08±1.38; P<.083), worse functional impairment [(LI: 0.49±1.15 vs 1.45±2.32, P<.001) (BIp: 34.6±32.9 vs 54.0±34.1, P<.001) (BIa: 5.79±12.5 vs 20.5±22.9, P<.001)], a higher percentage of functional loss at admission (85.9±23.2 vs 66.4±28.6; P<.0001), worse cognitive impairment (PT: 7.20±3.73 vs 5.10±3.69, P<.001) and malnutrition (albumin 2.67±0.54 vs 2.99±0.49, P<.001). Mortality was higher with impaired consciousness [49.2% (P<.01)], tachypnea [33.3% (P<.01)], tachycardia [44.4% (P<.002), high urea levels [31.8 (P<.001)], anemia [44.7% (P<.02)], pleural effusion [42.9% (P<.002)], and multilobar infiltrates [43.2% (P<.001)]. In the multivariate analysis, variables associated with mortality were: age≥90years [OR: 3.11 (95% CI: 1.31–7.36)], impaired consciousness [3.19 (1.66–6.15)], hematocrit<30% [2.87 (1.19–6.94)], pleural effusion [3.77 (1.69–8.39)] and multilobar infiltrates [2.76 (1.48–5.16)]. Female sex and a preserved functional status prior (LI≥5) and during admission (BIa≥40) were protective of mortality [0.40 (0.22–0.70), 0.09 (0.01–0.81) and 0.11 (0.02–0.51)].

ConclusionsGeriatric assessment parameters and routine clinical variables were associated with mortality.

Analizar la relación de parámetros obtenidos en la valoración geriátrica con la mortalidad en ancianos con neumonía extrahospitalaria (NEH) en una unidad de geriatría de agudos (UGA).

MétodoUn total de 456pacientes (≥75años). Variables: edad, sexo, procedencia, antecedentes, nivel de conciencia, frecuencia cardíaca y respiratoria, presión arterial, datos de laboratorio, derrame pleural, afectación multilobar, capacidad funcional (independencia para actividades de la vida diaria) previa al ingreso (índice de Lawton [IL], índice de Barthel previo [IBp]) y en el momento del ingreso (IBi), función cognitiva (test de Pfeiffer [TP]), comorbilidad (índice de Charlson [ICh]) y nutrición (proteínas totales, albúmina).

ResultadosLos 110pacientes que fallecieron durante el ingreso (24,2%) tuvieron mayor edad (86,6±6,4 vs 85,1±6,4; p<0,04), mayor comorbilidad (ICh 2,35±1,61 vs 2,08±1,38; p<0,083), menor capacidad funcional (IL: 0,49±1,15 vs 1,45±2,32; p<0,001; IBp: 34,6±32,9 vs 54,0±34,1; p<0,001; IBi: 5,79±12,5 vs 20,5±22,9; p<0,001), mayor porcentaje de pérdida funcional al ingreso (85,9±23,2 vs 66,4±28,6; p<0,0001), mayor deterioro cognitivo (TP: 7,20±3,73 vs 5,10±3,69; p<0,001) y mayor desnutrición (albúmina 2,67±0,54 vs 2,99±0,49; p<0,001). Hubo también mayor mortalidad con alteración de conciencia (49,2%; p<0,01), taquipnea (33,3%; p<0,01), taquicardia (44,4%; p<0,002), urea elevada (31,8; p<0,001), anemia (44,7%; p<0,02), derrame pleural (42,9%; p<0,002) y afectación multilobar (43,2%; p<0,001). En el análisis multivariado resultaron significativos: edad ≥90años (OR: 3,11 [IC95%: 1,31-7,36]), alteración de conciencia (3,19 [1,66-6,15]), hematocrito <30% (2,87 [1,19-6,94]), derrame pleural (3,77 [1,69-8,39]) y afectación multilobar (2,76 [1,48-5,16]). El sexo femenino y la capacidad funcional más conservada previa (IL≥5) y en el momento del ingreso (IBi≥40) fueron protectores de mortalidad (0,40 [0,22-0,70]; 0,09 [0,01-0,81] y 0,11 [0,02-0,51]).

ConclusionesLos parámetros de valoración geriátrica y las variables clínicas habituales estuvieron relacionados con la mortalidad.

The annual incidence of pneumonia in adults in population studies ranges from 5% to 11%. In Spain, the incidence is around 1.6–1.8 episodes/1000 inhabitants/year, predominantly in winter and in elderly men. The number of hospital admissions due to pneumonia increases with age (1.29/1000 in patients aged 18–39 years, compared to 13.21/1000 in patients over the age of 55). Mortality can range from 1% to 5% in outpatients and from 5.7% to 14% in hospitalized patients. This increases when mid to long-term mortality is evaluated, and figures of up to 8% at 90 days, 21% at 1-year and 36% at 5 years have been reported.1–3

Factors traditionally associated with greater mortality in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) are: underlying disease; mental deterioration; respiratory failure; multilobar involvement on X-ray; advanced age.4 Pneumonia severity can be evaluated using a number of instruments and indexes. Of particular value are the Fine or Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and the Confusion, Urea, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, age≥65 (CURB 65).5,6 Both indexes use clinical variables obtained from patient histories, physical examination and laboratory data, and have proved useful in identifying patients with disease severity requiring hospitalization. Although these indexes were not specifically designed for the geriatric population, they are valuable for predicting a prolonged hospital stay and mortality in elderly patients.7

Disease prognosis in the elderly is often influenced by the patient's underlying state of health, defined by nutritional status, mental status and functional capacity (level of independence for activities of daily living). Deterioration in these areas has been identified as a possible independent factor for mortality in elderly CAP patients.3,7–11

Few prognostic indexes currently used in clinical practice include these underlying health status variables. Comprehensive geriatric assessment is a working system that consists of a systematic evaluation using instruments and scales to determine the different health areas affecting the elderly patient: most importantly, functional capacity (level of independence for activities of daily living), cognitive function, nutritional status, and social and family environment.12 This systematic assessment is routinely undertaken in geriatric units.12,13 The aim of this study was to analyze the possible relationship between the parameters obtained from the geriatric assessment and in-hospital mortality in a group of very elderly CAP patients.

MethodParticipantsProspective study including all patients aged 75 years or older consecutively hospitalized with a diagnosis of CAP in an acute care geriatric unit (AGU) over a period of 5 years.

CAP diagnosis was based on clinical criteria (cough, secretion mobilization, expectoration, dyspnea and/or chest pain) and radiological confirmation (recently developed pulmonary infiltration on chest X-ray). All patients were admitted via the emergency room.

VariablesThe following variables were recorded on admission: age, sex, place of residence before admission, disease history, level of consciousness, heart and breathing rate, blood pressure, laboratory parameters (urea, sodium, blood glucose, hemoglobin and arterial pH), oxygen saturation, pleural effusion, multilobar involvement on chest X-ray. Many of these variables are included in the prognostic indexes most commonly used in clinical practice (PSI, CURB). All patients underwent comprehensive geriatric assessment including variables related to his/her prior status and variables collected at the time of admission. Functional status before admission was evaluated by determining the level of independence for instrumental activities of daily living with the Lawton index (LI) and for basic activities using the Barthel index (BIp).14,15 The data for these scales were collected from the patient and/or family members. The patient's pre-admission status regarding immobility syndrome, pressure ulcers (PU) and/or cognitive deterioration was recorded.

Functional capacity at the time of admission was also evaluated using the Barthel index (BIa) and the percentage of functional loss due to the acute episode was calculated using the formula [(BIp−BIa)/BIp×100]. Cognitive function was evaluated using the Pfeiffer test (PT),16 comorbidity [Charlson index (ChI)],17 immobility syndrome, PU, delirium and nutritional status (total proteins and serum albumin) were also recorded on admission.

Statistical AnalysisStatistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 software (IBM Corporation). Qualitative variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Student's t-test was used for associations between qualitative variables and quantitative variables. Statistical significance was set at P<.05. Finally, variables that showed significant association with greater mortality on the bivariate analysis were subsequently included in a binary logistic regression multivariate model.

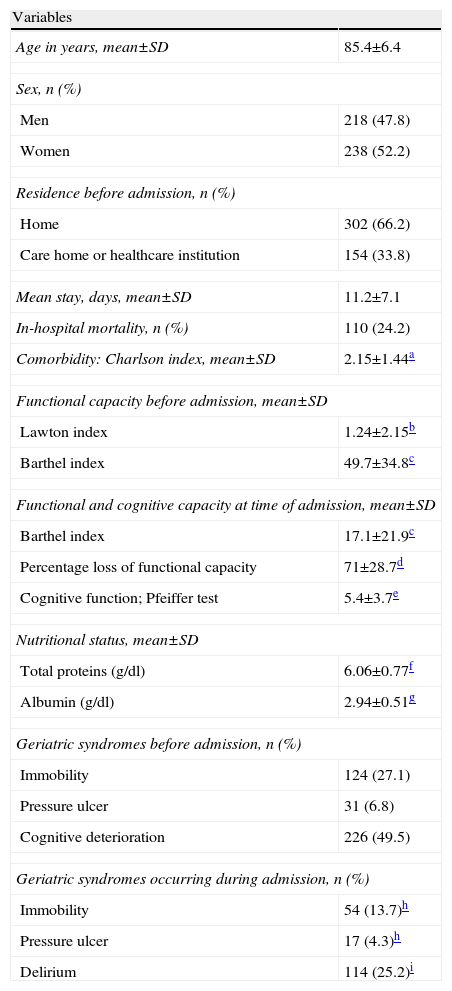

ResultsThe characteristics of the 456 patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. The sample comprises very elderly patients with a high mean age, many of whom were already dependent before admission for activities of daily living, as can be seen from the low mean LI and BIp scores. The patients were also very dependent at the time of admission with a mean BIa score of 17.1 (range 0–100). Moreover, mean cognitive function scores and nutritional parameters, such as albumin, were altered, and immobility syndrome and cognitive deterioration before admission were common. All these characteristics confirm that the sample consisted of a group of elderly patients in a compromised state of health.

Characteristics of the Overall Patient Sample: Sociodemographic Data and Parameters Obtained From the Geriatric Assessment (n=456).

| Variables | |

| Age in years, mean±SD | 85.4±6.4 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Men | 218 (47.8) |

| Women | 238 (52.2) |

| Residence before admission, n (%) | |

| Home | 302 (66.2) |

| Care home or healthcare institution | 154 (33.8) |

| Mean stay, days, mean±SD | 11.2±7.1 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 110 (24.2) |

| Comorbidity: Charlson index, mean±SD | 2.15±1.44a |

| Functional capacity before admission, mean±SD | |

| Lawton index | 1.24±2.15b |

| Barthel index | 49.7±34.8c |

| Functional and cognitive capacity at time of admission, mean±SD | |

| Barthel index | 17.1±21.9c |

| Percentage loss of functional capacity | 71±28.7d |

| Cognitive function; Pfeiffer test | 5.4±3.7e |

| Nutritional status, mean±SD | |

| Total proteins (g/dl) | 6.06±0.77f |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.94±0.51g |

| Geriatric syndromes before admission, n (%) | |

| Immobility | 124 (27.1) |

| Pressure ulcer | 31 (6.8) |

| Cognitive deterioration | 226 (49.5) |

| Geriatric syndromes occurring during admission, n (%) | |

| Immobility | 54 (13.7)h |

| Pressure ulcer | 17 (4.3)h |

| Delirium | 114 (25.2)i |

Range 0–8 points (0=maximum dependence and 8=maximum independence in instrumental activities of daily living).

Range 0–100 points (0=maximum dependence and 100=maximum independence in basic activities of daily living).

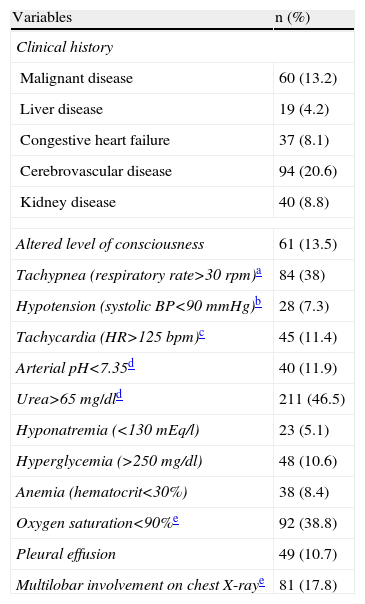

The clinical variables and laboratory data are given in Table 2, showing high rates of cerebrovascular disease, tachypnea, raised urea and low oxygen saturation. These same variables are considered in the Fine PSI index as indicative of poor prognosis and associated with greater mortality.5

Clinical and Laboratory Variables in Overall Patient Sample (n=456).

| Variables | n (%) |

| Clinical history | |

| Malignant disease | 60 (13.2) |

| Liver disease | 19 (4.2) |

| Congestive heart failure | 37 (8.1) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 94 (20.6) |

| Kidney disease | 40 (8.8) |

| Altered level of consciousness | 61 (13.5) |

| Tachypnea (respiratory rate>30rpm)a | 84 (38) |

| Hypotension (systolic BP<90mmHg)b | 28 (7.3) |

| Tachycardia (HR>125bpm)c | 45 (11.4) |

| Arterial pH<7.35d | 40 (11.9) |

| Urea>65mg/dld | 211 (46.5) |

| Hyponatremia (<130mEq/l) | 23 (5.1) |

| Hyperglycemia (>250mg/dl) | 48 (10.6) |

| Anemia (hematocrit<30%) | 38 (8.4) |

| Oxygen saturation<90%e | 92 (38.8) |

| Pleural effusion | 49 (10.7) |

| Multilobar involvement on chest X-raye | 81 (17.8) |

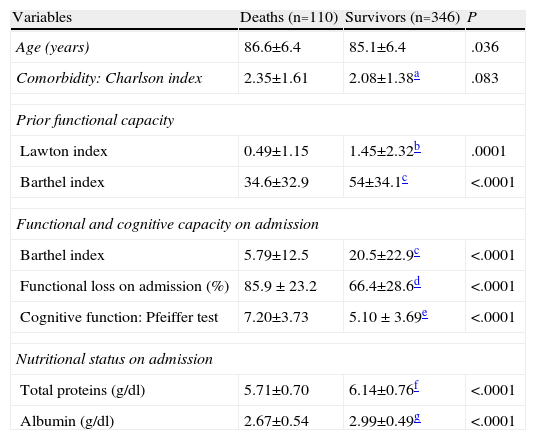

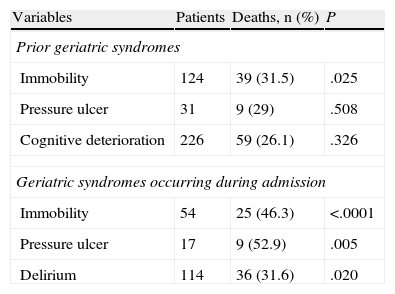

It can be seen from Table 3 that patients who died during admission had a higher comorbidity burden and were older. This table also shows that all parameters recorded in the geriatric assessment were significantly related with death during admission. Patients who died, therefore, had significantly lower mean LI, BIp, BIa and PT scores, indicating greater dependence in activities of daily living (both prior to and at admission) and poorer cognitive function. Moreover, the mean percentage loss of functional capacity caused by pneumonia was significantly greater in patients who died (85.9%±23.2% vs 66.4%±28.6%; P<.001). Nutritional parameters revealed mean total protein and albumin values below normal limits in all patients. Furthermore, these parameters were even lower, to a significant extent, in the group of patients who died. It can be seen from Table 4 that immobility, PU and delirium during admission were significantly more common in patients who died.

Quantitative Variables From the Geriatric Evaluation and Mortality During Admission (n=456) (Mean±DE).

| Variables | Deaths (n=110) | Survivors (n=346) | P |

| Age (years) | 86.6±6.4 | 85.1±6.4 | .036 |

| Comorbidity: Charlson index | 2.35±1.61 | 2.08±1.38a | .083 |

| Prior functional capacity | |||

| Lawton index | 0.49±1.15 | 1.45±2.32b | .0001 |

| Barthel index | 34.6±32.9 | 54±34.1c | <.0001 |

| Functional and cognitive capacity on admission | |||

| Barthel index | 5.79±12.5 | 20.5±22.9c | <.0001 |

| Functional loss on admission (%) | 85.9 ± 23.2 | 66.4±28.6d | <.0001 |

| Cognitive function: Pfeiffer test | 7.20±3.73 | 5.10 ± 3.69e | <.0001 |

| Nutritional status on admission | |||

| Total proteins (g/dl) | 5.71±0.70 | 6.14±0.76f | <.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.67±0.54 | 2.99±0.49g | <.0001 |

Range 0–8 points (0=maximum dependence and 8=maximum independence in instrumental activities of daily living).

Range 0–100 points (0=maximum dependence and 100=maximum independence in basic activities of daily living).

Qualitative Variables From the Geriatric Evaluation and Mortality During Admission (n=456).

| Variables | Patients | Deaths, n (%) | P |

| Prior geriatric syndromes | |||

| Immobility | 124 | 39 (31.5) | .025 |

| Pressure ulcer | 31 | 9 (29) | .508 |

| Cognitive deterioration | 226 | 59 (26.1) | .326 |

| Geriatric syndromes occurring during admission | |||

| Immobility | 54 | 25 (46.3) | <.0001 |

| Pressure ulcer | 17 | 9 (52.9) | .005 |

| Delirium | 114 | 36 (31.6) | .020 |

The percentage of deaths and statistical significance were calculated from the sample available for each variable.

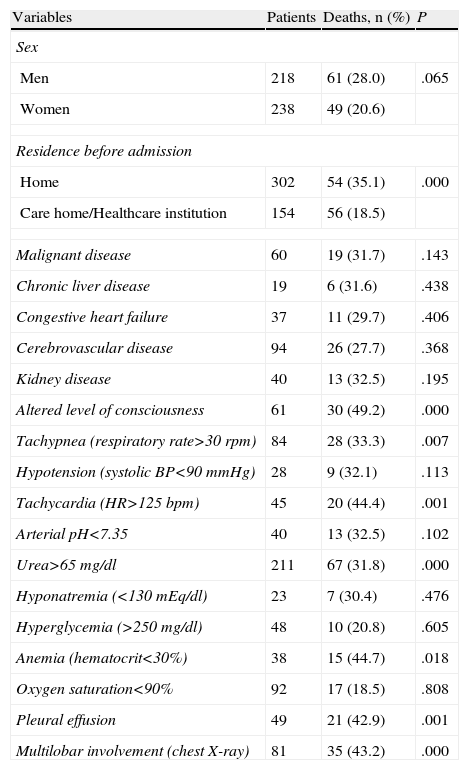

Table 5 shows the relationship between clinical variables and laboratory data and mortality. Male sex, admission from home, tachypnea, tachycardia, raised urea, anemia, pleural effusion and multilobar involvement on chest X-ray were significantly more common in patients who died.

Clinical, Analytical and Radiological Variables and Mortality During Admission (n=456).

| Variables | Patients | Deaths, n (%) | P |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 218 | 61 (28.0) | .065 |

| Women | 238 | 49 (20.6) | |

| Residence before admission | |||

| Home | 302 | 54 (35.1) | .000 |

| Care home/Healthcare institution | 154 | 56 (18.5) | |

| Malignant disease | 60 | 19 (31.7) | .143 |

| Chronic liver disease | 19 | 6 (31.6) | .438 |

| Congestive heart failure | 37 | 11 (29.7) | .406 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 94 | 26 (27.7) | .368 |

| Kidney disease | 40 | 13 (32.5) | .195 |

| Altered level of consciousness | 61 | 30 (49.2) | .000 |

| Tachypnea (respiratory rate>30rpm) | 84 | 28 (33.3) | .007 |

| Hypotension (systolic BP<90mmHg) | 28 | 9 (32.1) | .113 |

| Tachycardia (HR>125bpm) | 45 | 20 (44.4) | .001 |

| Arterial pH<7.35 | 40 | 13 (32.5) | .102 |

| Urea>65mg/dl | 211 | 67 (31.8) | .000 |

| Hyponatremia (<130mEq/dl) | 23 | 7 (30.4) | .476 |

| Hyperglycemia (>250mg/dl) | 48 | 10 (20.8) | .605 |

| Anemia (hematocrit<30%) | 38 | 15 (44.7) | .018 |

| Oxygen saturation<90% | 92 | 17 (18.5) | .808 |

| Pleural effusion | 49 | 21 (42.9) | .001 |

| Multilobar involvement (chest X-ray) | 81 | 35 (43.2) | .000 |

The percentage of deaths and statistical significance were calculated from the sample available for each variable.

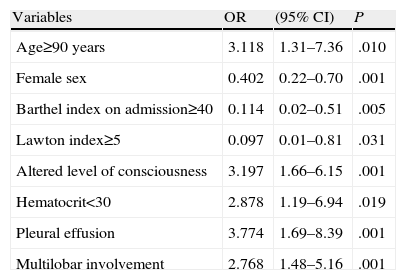

Lastly, Table 6 shows variables significantly related with mortality in the multivariate analysis. Age≥90 years, altered consciousness, anemia, pleural effusion and multilobar involvement present an elevated relative risk of death with OR values higher than 1. Female sex and better functional capacity (BIa≥40; LI≥5) present a relative risk of less than 1, suggesting that these variables may act as protective factors against mortality.

Variables Related With Mortality During Admission in Elderly Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia.

| Variables | OR | (95% CI) | P |

| Age≥90 years | 3.118 | 1.31–7.36 | .010 |

| Female sex | 0.402 | 0.22–0.70 | .001 |

| Barthel index on admission≥40 | 0.114 | 0.02–0.51 | .005 |

| Lawton index≥5 | 0.097 | 0.01–0.81 | .031 |

| Altered level of consciousness | 3.197 | 1.66–6.15 | .001 |

| Hematocrit<30 | 2.878 | 1.19–6.94 | .019 |

| Pleural effusion | 3.774 | 1.69–8.39 | .001 |

| Multilobar involvement | 2.768 | 1.48–5.16 | .001 |

Mortality among elderly CAP patients in this study was 24%, higher than that reported by other authors.2,7,9 This may be due to 3 factors:

- 1.

The study was performed in a specific geriatric care unit that only accepted patients over 75 years of age; our patients, therefore, were of advanced age.

- 2.

The study was performed in a hospitalization unit, so all patients had pneumonia requiring admission and presented more criteria for severity (see Table 2 showing a high rate of factors for hospital admission and poor prognosis).

- 3.

Many of our elderly patients were dependent for activities of daily living before admission, suggesting that their baseline health status was poor.

Age is a strong indicator for mortality in patients with pneumonia, as has been reported by numerous authors.18–21 In this study, age was also significantly related with greater mortality in both the univariate and multivariate analyses. In the latter, mortality rate was three times higher in patients aged≥90. The interesting point here is that even among a homogeneous sample in which almost all subjects are very elderly (i.e., where it is more difficult to differentiate between individuals purely on the basis of age), extreme ages of 90 or older continue to have predictive value and can differentiate a group with poorer prognosis. With regard to comorbidities, no statistically significant relationship with mortality was found in this study. In contrast, other authors such as Nakagawa et al.22 report a 30% mortality in patients with ChI>3. These divergent results may be due to the different characteristics of the study populations.

In most studies, a greater prevalence of CAP is reported in men,1 but in our study, there were slightly more women (Table 1). This is probably due to the greater prevalence of women among geriatric populations. In this study, mortality among women was slightly lower than among men, and in the multivariate analysis, female sex was a protective factor against mortality (Table 6). This finding coincides with other studies in which higher mortality was observed among men.5,6

This study was conducted in a group of very elderly patients with a generally very poor health status. Nevertheless, the clinical variables and laboratory data usually used as predictive factors for mortality and are generally included in other prognostic indexes (PSI and CURB) continue to have a significant predictive value, as shown in Table 4. It can be seen here that tachypnea, tachycardia, raised urea, anemia, pleural effusion and multilobar involvement are significantly associated with greater mortality. Temperature could not be analyzed since it was recorded dichotomously, as indicated by the PSI (≤35° or ≥40°). None of our patients met this criterion. Moreover, none of the underlying diseases usually recognized as prognostic factors in other studies were significantly related to greater mortality. This would suggest that in the geriatric population, the severity of the acute process and the underlying health status of the elderly person carry more weight than specific comorbidities. Altered consciousness stands out as a variable that is strongly predictive of mortality in both the univariate and the multivariate analyses. These results underline the importance of mental state as a prognostic indicator in elderly patients with acute disease.8,18,21,23 The importance of the altered level of consciousness variable can be explained by the appearance of hypoactive delirium, a common clinical situation in this population that is directly related with in-hospital mortality, irrespective of associated pathology.24,25 The high prevalence of altered consciousness in our study may be due to the fact that our population was very elderly and presented multiple risk factors for delirium. A significant relationship between delirium and in-hospital mortality in elderly subjects with pneumonia has been described in other studies. This relationship was also identified in our population with the univariate analysis (Table 4), although statistical significance was not reached on the multivariate analysis. This may be due to the under-diagnosis of delirium, this being more difficult to determine than mere altered consciousness.7,8,26

Plasma urea is included in the main indexes for predicting mortality in CAP (CURB 65, PSI). It was also identified in our study as a predictive factor in the univariate, but not in the multivariate, analysis. This may be explained by the existence of other, more potent, factors in this elderly population. Ewig et al.7 suggested that urea may not be a very specific predictor of mortality in the elderly, as this is a disturbance commonly found in this population. In contrast, in our study and in other publications,6,8,27 anemia and malnutrition, also common in the elderly, were prognostic factors for mortality. Nevertheless, only anemia reached statistical significance in the multivariate analysis, suggesting that it can be regarded as a potent prognostic indicator (Table 6). The predictive value of these variables may be explained by both anemia and malnutrition being indirect indicators of a poorer state of health that may also be related with underlying disease.

A better functional capacity prior to and at admission was a protective factor against in-hospital mortality. Several authors have underlined the importance of functional capacity as a predictor of mortality in various diseases.3,10,11,28 Marrie and Wu9 found that functional status is a strong predictor of in-hospital death in patients with CAP. Likewise, Davis et al.3 reported that prior functional status has a similar or better predictive value for in-hospital mortality than laboratory data. Torres et al., 10 also using the Barthel index, similarly concluded that a better prior functional status acts as a protective factor against death after an episode of CAP. In contrast with these findings, Ma et al.2 did not find a significant relationship between functional capacity and mortality; these differences may be due to the use of different scales and the different characteristics of the populations studied.

Geriatric syndromes give an overall view of the clinical and functional status of the patient and are indicators of the morbidity and mortality produced by different diseases.8,9,28 These syndromes are generally interrelated, and the appearance of one often leads to the appearance of another, so it is sometimes difficult to evaluate each individually. A significant relationship was found in the univariate analysis between geriatric symptoms and mortality, although this was not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis. This may be because all elderly patients included in this study had pneumonia that met admission criteria, indicating severe disease. This could suggest that the severity of the pneumonia might have influenced mortality more than the geriatric syndromes. Even so, immobility appears to one of the most significant of the geriatric syndromes: in their study, Marrie and Wu9 found that it produces a risk of in-hospital death in CAP of up to 25%, compared to a 4% risk in patients who could walk unaided. Similarly, Riquelme et al.29 reported a relative risk of mortality of 10.7 in bedridden patients.

As we have seen, the parameters obtained in the geriatric assessment have proven their value in the prognosis of mortality in elderly subjects with CAP, as confirmed in our study (Tables 3 and 4). Although the multivariate analysis suggests that age and clinical and laboratory variables are useful for establishing a short-term prognosis of death in a very elderly population, some variables obtained from the geriatric assessment are also very useful for predicting mortality. Functional capacity (greater level of independence) was identified as a protective factor against death and an indicator of good prognosis in the multivariate analysis (Table 5). Nevertheless, the need for similar studies with larger populations of elderly subjects must be emphasized.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors state that they have no direct or indirect conflicts of interest related to the contents of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Calle A, Márquez MA, Arellano M, Pérez LM, Pi-Figueras M, Miralles R. Valoración geriátrica y factores pronósticos de mortalidad en pacientes muy ancianos con neumonía extrahospitalaria. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:429–434.