Fungal infections have increased in the last few decades as a result of the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the growing number of immunocompromised patients in our clinics, which have led to changes in the saprophytic microorganisms usually isolated. Even so, fungal empyemas are still rare entities, with a mortality rate of over 70%. The most common ways for fungi to reach the pleural cavity are via lung infections, complications of pre-existing chronic empyemas, esophageal-bronchial fistulas, or repeated thoracentesis,1 so in patients with risk factors, the possibility of a fungal etiology must be taken into account.

We report a retrospective analysis of exclusively fungal pleural effusions diagnosed in our hospital between 2005 and 2016. Aseptic sampling of pleural fluids was performed by thoracentesis or endothoracic drainage; the samples underwent microbiological processing including culture, identification using biochemical galleries and mass spectrometry, direct observation by electron microscopy in the case of filamentous fungi, followed by antifungal sensitivity testing using commercial Sensititre® Yeast One panels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK).

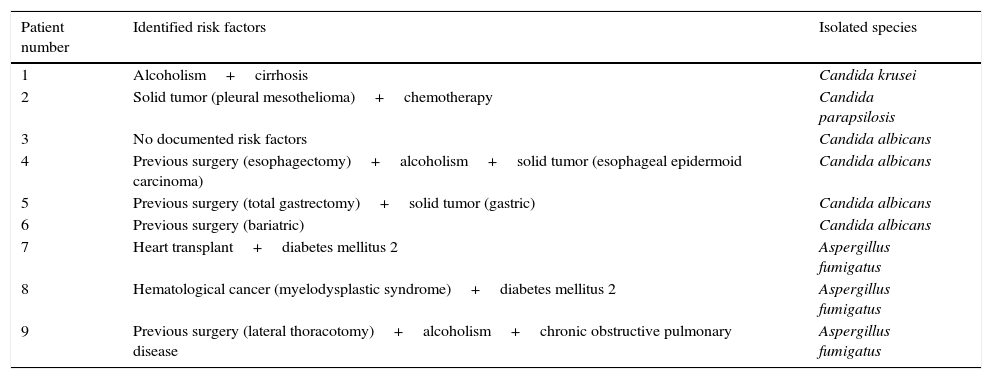

Fungal isolates were obtained from 9 patients (8 males with a median age of 65±10 years) characterized by nonspecific symptoms (respiratory failure and dyspnea), a 5-week mortality rate of 50%, and long hospital stays (47±24 days). Seven yeasts (2 non-Candida albicans species) and 3 Aspergillus fumigatus (A. fumigatus) were isolated, and no resistance was documented. The total rate of antifungal therapy was 55%, the most common being azole derivatives, and the least common, caspofungin or inhaled liposomal amphotericin B. None of the patients had received antifungal prophylaxis prior to the study episode. Table 1 lists the risk factors for fungal infection identified in each patient and the species isolated in each case.

Risk factors in patients with fungal pleural effusion and species isolated.

| Patient number | Identified risk factors | Isolated species |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alcoholism+cirrhosis | Candida krusei |

| 2 | Solid tumor (pleural mesothelioma)+chemotherapy | Candida parapsilosis |

| 3 | No documented risk factors | Candida albicans |

| 4 | Previous surgery (esophagectomy)+alcoholism+solid tumor (esophageal epidermoid carcinoma) | Candida albicans |

| 5 | Previous surgery (total gastrectomy)+solid tumor (gastric) | Candida albicans |

| 6 | Previous surgery (bariatric) | Candida albicans |

| 7 | Heart transplant+diabetes mellitus 2 | Aspergillus fumigatus |

| 8 | Hematological cancer (myelodysplastic syndrome)+diabetes mellitus 2 | Aspergillus fumigatus |

| 9 | Previous surgery (lateral thoracotomy)+alcoholism+chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Aspergillus fumigatus |

As in other series with larger numbers of cases,1,2 the causative agents associated with fungal empyema that presented a slightly lower mortality rate in our series were Candida spp. followed by A. fumigatus. All patients except one had 1 or more previous immunodeficiency diseases according to the accepted classifications1: cancer, diabetes mellitus, long-term steroid treatment, hepatic cirrhosis, solid organ transplant, alcoholism, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or surgery in the 4 weeks prior to isolation of the fungus.

Clinical suspicion, chest drainage, early introduction of antifungal agents, and long-term treatment are associated with a reduced mortality rate.1 However, the treatment of fungal empyema is not protocolized, and combinations that include several drugs can be used (amphotericin B and voriconazole, echinocandins) due the variable penetration of systemically administered antifungals into the pleural cavity.3,4 The percentage of patients treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was higher than that of patients treated with antifungal drugs, despite determination of the etiology, and no subsequent antibiotic de-escalation was performed.

The lack of specific antifungal treatment may be due to clinicians’ failure to consider fungi as true pathogens. Each case must be studied on an individual basis and the role of each causative agent must be evaluated in order to optimize treatment. This includes the need for pharmacological prophylaxis in patients at high risk of developing fungal empyema (hemodialysis, post-surgical re-exploration, environmental colonization by Aspergillus, or documented cytomegalovirus infection).5

The seriousness of this entity and its devastating consequences in patients should not be underestimated.

Please cite this article as: de Vega Sánchez B, López Ramos I, Ortiz de Lejarazu R, Disdier Vicente C. Empiema fúngico: una entidad infrecuente con elevada mortalidad. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:641–642.