Up to 50% of patients with nasal polyposis (NP) present with comorbid asthma,1 suggesting that NP and asthma could share the same underlying pathophysiological mechanism. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) may be indicated in patients with severe NP and comorbid asthma who fail to respond to intensive medical therapy. The clinical impact of FESS on asthma symptoms has been evaluated in a small but growing number of studies2–6 that have shown that surgery improves subjective measures of disease control and quality of life (QoL)7; however, the impact of FESS on objective measures of disease control remains uncertain given the heterogenous findings of those studies.

Although the precise mechanism by which surgery improves asthma symptoms is not well-understood, some authors8 have posited that this improvement may be attributable to the postoperative reduction in tissues with severe nasal inflammation, leading to lower eosinophil production, chemotaxis, and, consequently, decreased bronchial inflammation. To our knowledge, however, none of the aforementioned studies have assessed changes in bronchial inflammation after FESS. We hypothesized that eosinophilic bronchial inflammation would decrease after sinus surgery, resulting in improved clinical and functional asthma control. To test this hypothesis, we performed a prospective, multi-institutional proof-of-concept clinical study to evaluate the impact of bilateral FESS on patients with comorbid asthma and severe NP. Outcome measures were pre-post changes in: (1) bronchial inflammation, (2) disease control and exacerbations), (3) lung function, and (4) QoL.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 18–70 years, (2) diagnosis of asthma, (3) diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis, and (4) bilateral, grade II–III NP (Lildholdt classification) with an indication for bilateral FESS. The study complies with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was presented to the Ethics Committee at the coordinating centre. All patients provided signed informed consent and all personal data were anonymised. Three study visits were scheduled. Visit 1 was performed 30 days prior to surgery to confirm the diagnosis and surgical indication, and administer baseline questionnaires and tests (including a prick-test for common aeroallergens). The surgical procedure was performed as described elsewhere,2 with postoperative administration of oral steroids allowed for ≤14 days and prophylactic antibiotics and topical nasal steroids prescribed according to POLINA consensus criteria. Visits 2 and 3 were scheduled postoperatively, respectively, at weeks 5 (±1) and 30 (±2).

The following tests were performed in all patients at all study visits: spirometry with bronchodilator test; eosinophil count in serum and induced sputum; fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FENO); Asthma Control Test (ACT); and the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (mini-AQLQ).

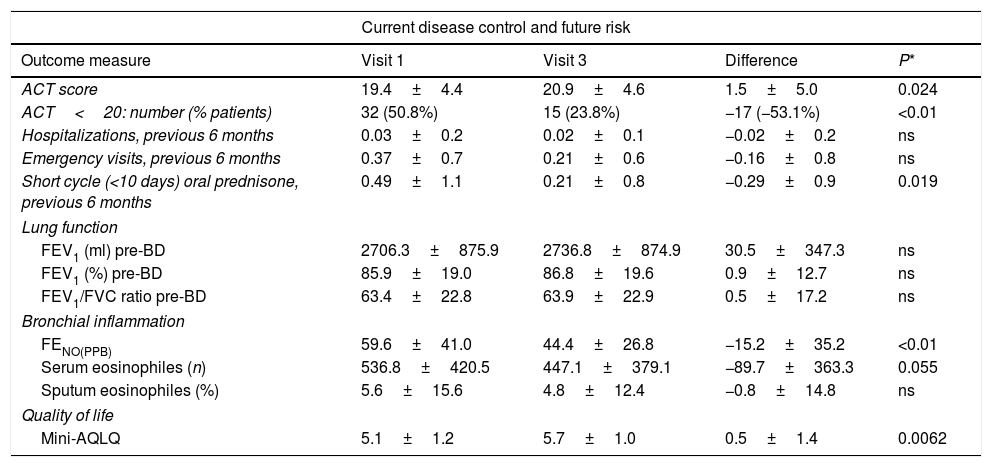

Sixty-three patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. To minimize the possible influence of changes in the inhaled anti-inflammatory asthma treatment on bronchial inflammation, no substantial changes were permitted during the study period in the patients included in the final analysis. The mean age (SD) was 50.8 (12.3) years and 52.4% were men. The table shows changes in the study variables from baseline (preoperative) to the final study visit (6 months after surgery).

At six months of follow-up, statistically significant changes were observed in several clinical parameters (Table 1), including an improvement in ACT scores, a fifty percent decrease in the percentage of patients with poor disease control (ACT<20), 18 (24.6%) patients increased by more than 3 points the ACT score in visit 3, and a reduction in oral prednisone use. There was also a significant decrease in FENO and a trend (p=0.055) towards lower serum eosinophile counts. QoL improved significantly. No significant changes were observed in hospitalizations or emergency department visits, nor in lung function parameters.

Changes in clinical parameters from baseline to final postoperative assessment 6 months after surgery.

| Current disease control and future risk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measure | Visit 1 | Visit 3 | Difference | P* |

| ACT score | 19.4±4.4 | 20.9±4.6 | 1.5±5.0 | 0.024 |

| ACT<20: number (% patients) | 32 (50.8%) | 15 (23.8%) | −17 (−53.1%) | <0.01 |

| Hospitalizations, previous 6 months | 0.03±0.2 | 0.02±0.1 | −0.02±0.2 | ns |

| Emergency visits, previous 6 months | 0.37±0.7 | 0.21±0.6 | −0.16±0.8 | ns |

| Short cycle (<10 days) oral prednisone, previous 6 months | 0.49±1.1 | 0.21±0.8 | −0.29±0.9 | 0.019 |

| Lung function | ||||

| FEV1 (ml) pre-BD | 2706.3±875.9 | 2736.8±874.9 | 30.5±347.3 | ns |

| FEV1 (%) pre-BD | 85.9±19.0 | 86.8±19.6 | 0.9±12.7 | ns |

| FEV1/FVC ratio pre-BD | 63.4±22.8 | 63.9±22.9 | 0.5±17.2 | ns |

| Bronchial inflammation | ||||

| FENO(PPB) | 59.6±41.0 | 44.4±26.8 | −15.2±35.2 | <0.01 |

| Serum eosinophiles (n) | 536.8±420.5 | 447.1±379.1 | −89.7±363.3 | 0.055 |

| Sputum eosinophiles (%) | 5.6±15.6 | 4.8±12.4 | −0.8±14.8 | ns |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Mini-AQLQ | 5.1±1.2 | 5.7±1.0 | 0.5±1.4 | 0.0062 |

Abbreviations: ACT, asthma control test; pre-BD, prior to bronchodilator testing; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; FENO, fraction of exhaled nitric oxide; Mini-AQLQ, mini asthma quality of life questionnaire; ns, not significant; PPB, parts per billion.

These findings show that bilateral FESS improved disease control, reduced bronchial inflammation, and improved QoL in this sample of patients with comorbid asthma and severe NP. However, surgery had no significant impact on lung function parameters. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the effect of FESS on bronchial inflammation in this patient population. The significant reduction in FENO and the nearly significant decrease in eosinophil counts suggest that surgery may have a direct, positive impact on bronchial inflammation, providing further support for the unified airway hypothesis.

The impact of FESS on asthma symptoms remains unclear, mainly due to the limited number of studies that have investigated this issue and to methodological limitations (e.g., small sample size, retrospective design) of those studies. Nonetheless, the body of evidence continues to grow. In 2013, Vashita et al.5 published a systematic review and meta-analysis, which concluded that FESS improves clinical measures of asthma but not lung function in patients with concomitant chronic rhinosinusitis and bronchial asthma, a finding that is consistent with our data. More recently (2019) Cao et al.9 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 studies (421 patients), finding—in contrast to Vashita et al.6—that FESS was associated with significant improvements in several lung function parameters (FEV1, FEF25-75%, and PEF). However, as Cao and colleagues observed, that association was based on low-quality evidence and thus no definitive conclusions can be made at present.

The findings of our study demonstrate, for the first time, that bilateral FESS appears to reduce bronchial inflammation in patients with asthma and comorbid NP. Although this decrease in bronchial inflammation should theoretically improve lung function, we did not detect any significant changes in those parameters. These findings provide additional data to support the positive impact of FESS on asthma control. Based on the totality of the available evidence, including our data, FESS appears to improve both disease control and QoL in these patients.

The main limitations of this study are the lack of a control group and the limited follow up, which makes it is difficult to make definitive conclusions based on the study data. Consequently, larger, prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to better elucidate the impact of FESS on objective measures of bronchial inflammation in this patient population.

This study is the most comprehensive conducted to date in patients undergoing FESS for comorbid asthma and severe NP. Our findings seem to point to a significant postoperative reduction in bronchial inflammation and better asthma control providing additional evidence for the unified airway hypothesis and supporting the use of endoscopic sinus surgery in patients with comorbid NP and asthma.

FundingGrants from SEPAR 2014 and Menarini (Spain). These sponsors had neither role in the design of this study nor in the analyses, data interpretation, or decision to submit results.

AuthorshipV.P. takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and had full access to all data, including adverse effects. V.P. drafted the manuscript with critical revision from all co-authors. V.P., L.S., J.R.G., S.Q., G.S., A.C., F.A. all contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interestsIn the last three years, V.P. has received honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings from Astrazeneca, Chiesi and Novartis. He also received financial support from Astrazeneca, Chiesi and Novartis to cover travel expenses to meetings. He acts as a consultant for ALK, Astrazeneca, Boehringer, MundiPharma and Sanofi. He has received funding/grant support for research projects from a variety of government agencies and not-for-profit foundations, as well as AstraZeneca, Chiesi and Menarini.

F.A. declares that in the last three years he has received fees for advisory work, lectures or grants to attend conferences and scientific meetings by ALK, Astrazeneca, Bial, Boheringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis and TEVA.

A.C. reports grants and honoraria from SEPAR, and grants from Menarini during the conduct of the study; grants from MYLAN; honoraria from ALK, Myland, MSD, and GSK; grants and honoraria from FAES Pharma, Novartis, Allakos, and Sanofi, outside of the currently submitted work.

G.S. declares having received in the last three years honoraria for participating as a speaker in meetings sponsored by Astrazeneca, ALK, Boehringer, and Novartis and as a consultant for AstraZeneca, GSK, Chiesi, Novartis, Rovi and Bial. He received financial support from Boehringer, Menarini and Novartis to attend congresses, and had received grants for research projects from Novartis and Boehringer.

In the last three years, S.Q. has received honoraria from ALK, AstraZeneca, Boehringer, Chiesi, GSK, Leti, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva for the organization of educational events, advisory boards, and speaking at sponsored meetings.

In the last three years, S.S.C. has received honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings from Astrazeneca, Chiesi, Novartis and GSK. S.S.C. has also received financial support from Chiesi, Menarini and Novartis for travel expenses to attend meetings.

J.R.G. declares no conflicts of interest.

C.C. received honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings from Astrazeneca, GSK, TEVA, Menarini, Mundipharma and Novartis. C.C. has received financial support from Chiesi, TEVA, Menarini and Mundipharma for travel expenses to meetings. C.C. acts as a consultant for ALK, Astrazeneca, MundiPharma, TEVA, GSK and Novartis.

In the last three years, E.E.M. has received speaking honoraria from Astra Zeneca, GSK, Mundipharma, Pzifer and ALK. E.E.M. has also received financial support from Astrazeneca, Novartis, FAES, Menarini and Chiesi for travel expenses to meetings. E.E.M. acts as a consultant for ALK, Astrazeneca, Boehringer, Mundipharma, Sanofi, TEVA and GSK.

A.G.B. declares to have received fees for speaking and attending conferences and scientific meetings from Astrazeneca, Chiesi, GSK, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis and TEVA.

In the last three years, C.S. has received honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings from Astrazeneca, Chiesi, GSK and Ferrer. C.S. has also received financial supor from Teva and Novartis for travel expenses to meetings.

In the last three years, L.R.S. has received fees for lectures or grants to attend conferences and scientific meetings by GSK, Menarini, FAES, Astrazeneca, Chiesi, Mundipharma, Stallergennes, Leti, Hal-Allergy, Allergy-Therapeutics, Immunotek. L.R.S. has also received funding/grant support for research projects from SEAIC (Sociedad Española de Alergia e Inmunología Clínica) and SEPAR (Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica).

In the last three years, I.L. has received fees for speaking at sponsored meetings and attending conferences and scientific meetings from Astrazeneca, Chiesi, Menarini, GSK, Esteve, Mundipharma, Roche, ALK, Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis.

We thank Bradley Londres for professional English language editing and Rosa Palomino, from Oblikue, for performing the statistical analysis.