Despite the numerous strategic plans for the prevention and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that have been implemented to date, high prevalence, underdiagnosis, and burden of care all remain a challenge in clinical practice1–4. Some of the main difficulties in COPD management include the prioritization and degree of control of treatable traits, and problems with inhaled therapy, such as device selection and patient adherence to prescribed maintenance treatment3,5–8. Moreover, new care strategies and, above all, new therapeutic strategies are scene-changers in the clinical management of COPD. The aim of this study was to reach a consensus among COPD experts on controversial issues in the evaluation and treatment of the disease, using Delphi methodology9.

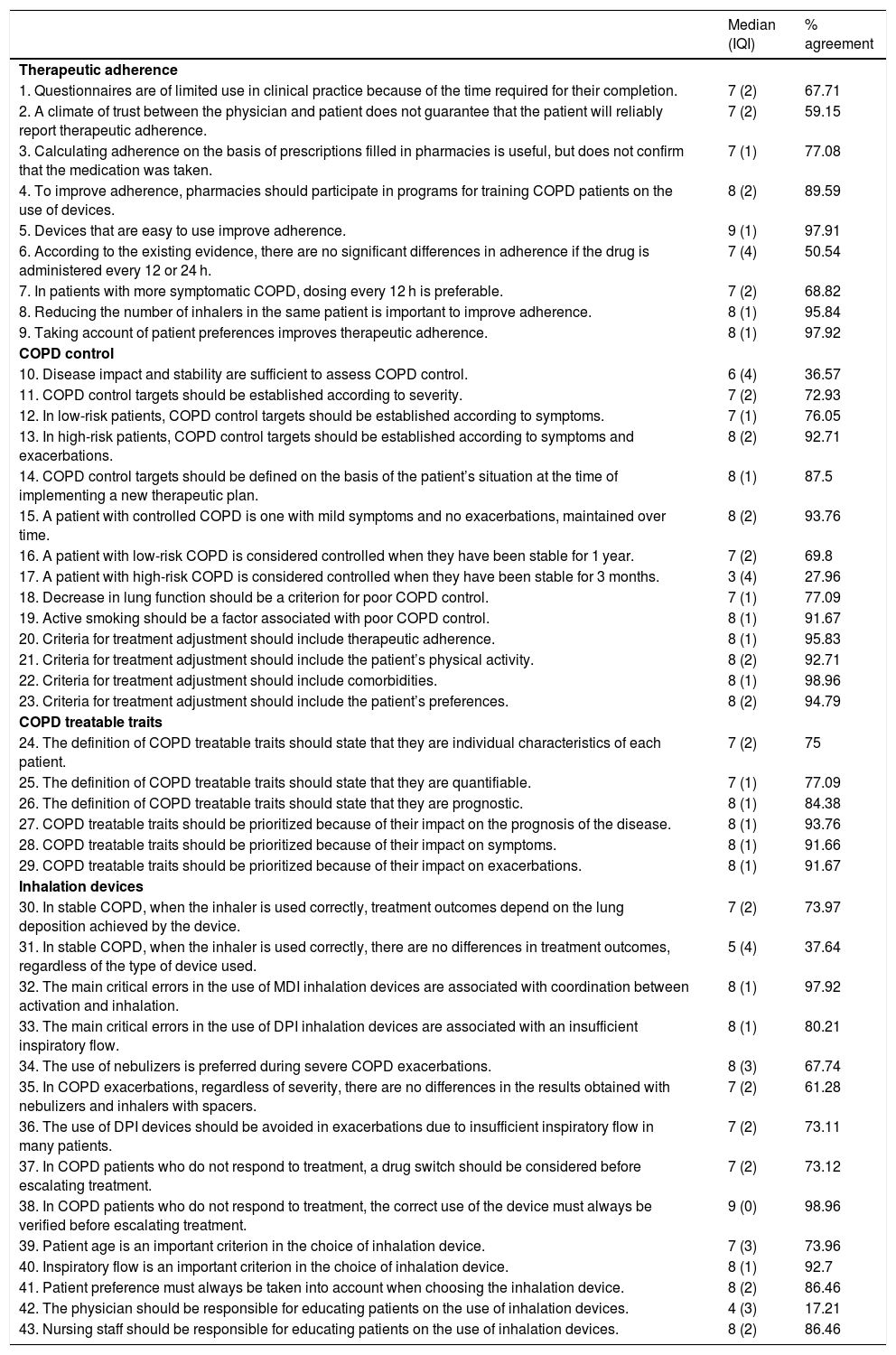

A scientific committee of 17 COPD experts participated in the project. The project coordinators selected a committee of SEPAR members whose profile demonstrated a consolidated background in COPD supported by publications, while ensuring that the whole of Spain was represented by regions. The committee analyzed the scientific evidence in four areas: therapeutic adherence, COPD control, COPD treatable traits, and inhalation devices. This evidence was then examined in 15 discussion sessions, to which 5 attending pulmonologists from each area were invited, selected by the expert committee. Using the information obtained at these meetings, a questionnaire of 43 statements (Table 1) was developed and sent to a panel of 95 experienced COPD pulmonologists who were asked to grade them on a Likert scale of 1–9. Statements that were scored 1–3 (disagreement, median ≤3) or 7–9 (agreement, median ≥7) by more than two-thirds of the panelists, were considered to have achieved consensus. When more than two-thirds scored a statement in the range of 4–6, it was considered inconclusive. After two consecutive rounds, consensus was reached on 37 statements: 36 in agreement (83.7%) and one in disagreement (2.3%). Only six statements (14%) failed to achieve consensus. Table 1 shows the scores and the degree of agreement for each statement.

Results obtained by the panel of experts after 2 rounds of consultations.

| Median (IQI) | % agreement | |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic adherence | ||

| 1. Questionnaires are of limited use in clinical practice because of the time required for their completion. | 7 (2) | 67.71 |

| 2. A climate of trust between the physician and patient does not guarantee that the patient will reliably report therapeutic adherence. | 7 (2) | 59.15 |

| 3. Calculating adherence on the basis of prescriptions filled in pharmacies is useful, but does not confirm that the medication was taken. | 7 (1) | 77.08 |

| 4. To improve adherence, pharmacies should participate in programs for training COPD patients on the use of devices. | 8 (2) | 89.59 |

| 5. Devices that are easy to use improve adherence. | 9 (1) | 97.91 |

| 6. According to the existing evidence, there are no significant differences in adherence if the drug is administered every 12 or 24 h. | 7 (4) | 50.54 |

| 7. In patients with more symptomatic COPD, dosing every 12 h is preferable. | 7 (2) | 68.82 |

| 8. Reducing the number of inhalers in the same patient is important to improve adherence. | 8 (1) | 95.84 |

| 9. Taking account of patient preferences improves therapeutic adherence. | 8 (1) | 97.92 |

| COPD control | ||

| 10. Disease impact and stability are sufficient to assess COPD control. | 6 (4) | 36.57 |

| 11. COPD control targets should be established according to severity. | 7 (2) | 72.93 |

| 12. In low-risk patients, COPD control targets should be established according to symptoms. | 7 (1) | 76.05 |

| 13. In high-risk patients, COPD control targets should be established according to symptoms and exacerbations. | 8 (2) | 92.71 |

| 14. COPD control targets should be defined on the basis of the patient’s situation at the time of implementing a new therapeutic plan. | 8 (1) | 87.5 |

| 15. A patient with controlled COPD is one with mild symptoms and no exacerbations, maintained over time. | 8 (2) | 93.76 |

| 16. A patient with low-risk COPD is considered controlled when they have been stable for 1 year. | 7 (2) | 69.8 |

| 17. A patient with high-risk COPD is considered controlled when they have been stable for 3 months. | 3 (4) | 27.96 |

| 18. Decrease in lung function should be a criterion for poor COPD control. | 7 (1) | 77.09 |

| 19. Active smoking should be a factor associated with poor COPD control. | 8 (1) | 91.67 |

| 20. Criteria for treatment adjustment should include therapeutic adherence. | 8 (1) | 95.83 |

| 21. Criteria for treatment adjustment should include the patient’s physical activity. | 8 (2) | 92.71 |

| 22. Criteria for treatment adjustment should include comorbidities. | 8 (1) | 98.96 |

| 23. Criteria for treatment adjustment should include the patient’s preferences. | 8 (2) | 94.79 |

| COPD treatable traits | ||

| 24. The definition of COPD treatable traits should state that they are individual characteristics of each patient. | 7 (2) | 75 |

| 25. The definition of COPD treatable traits should state that they are quantifiable. | 7 (1) | 77.09 |

| 26. The definition of COPD treatable traits should state that they are prognostic. | 8 (1) | 84.38 |

| 27. COPD treatable traits should be prioritized because of their impact on the prognosis of the disease. | 8 (1) | 93.76 |

| 28. COPD treatable traits should be prioritized because of their impact on symptoms. | 8 (1) | 91.66 |

| 29. COPD treatable traits should be prioritized because of their impact on exacerbations. | 8 (1) | 91.67 |

| Inhalation devices | ||

| 30. In stable COPD, when the inhaler is used correctly, treatment outcomes depend on the lung deposition achieved by the device. | 7 (2) | 73.97 |

| 31. In stable COPD, when the inhaler is used correctly, there are no differences in treatment outcomes, regardless of the type of device used. | 5 (4) | 37.64 |

| 32. The main critical errors in the use of MDI inhalation devices are associated with coordination between activation and inhalation. | 8 (1) | 97.92 |

| 33. The main critical errors in the use of DPI inhalation devices are associated with an insufficient inspiratory flow. | 8 (1) | 80.21 |

| 34. The use of nebulizers is preferred during severe COPD exacerbations. | 8 (3) | 67.74 |

| 35. In COPD exacerbations, regardless of severity, there are no differences in the results obtained with nebulizers and inhalers with spacers. | 7 (2) | 61.28 |

| 36. The use of DPI devices should be avoided in exacerbations due to insufficient inspiratory flow in many patients. | 7 (2) | 73.11 |

| 37. In COPD patients who do not respond to treatment, a drug switch should be considered before escalating treatment. | 7 (2) | 73.12 |

| 38. In COPD patients who do not respond to treatment, the correct use of the device must always be verified before escalating treatment. | 9 (0) | 98.96 |

| 39. Patient age is an important criterion in the choice of inhalation device. | 7 (3) | 73.96 |

| 40. Inspiratory flow is an important criterion in the choice of inhalation device. | 8 (1) | 92.7 |

| 41. Patient preference must always be taken into account when choosing the inhalation device. | 8 (2) | 86.46 |

| 42. The physician should be responsible for educating patients on the use of inhalation devices. | 4 (3) | 17.21 |

| 43. Nursing staff should be responsible for educating patients on the use of inhalation devices. | 8 (2) | 86.46 |

DPI: dry powder inhalers; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQI: interquartile interval; MDI: metered dose inhalers.

White: agreement consensus; dark gray: disagreement consensus; light gray: no consensus.

Seven of the nine statements on therapeutic adherence reached a consensus of agreement. The panelists believed that trust between the physician and the patient was important but noted that the information provided by the latter is not always reliable. Although there was no consensus on whether adherence to 12- and 24-h regimens differed significantly, panelists agreed (68.82%) that the 12-h regimen is preferable in patients with more symptomatic COPD. It was agreed that in order to increase adherence, the number of inhalers should be reduced and the patient’s preferences must be taken into account.

Consensus agreement was achieved in 12 of the 14 statements on COPD control. A high percentage (>72%) agreed that control targets should be established on the basis of severity, symptoms, exacerbations, lung function, and smoking habit. Only 36.57% considered that disease impact and stability were sufficient to assess COPD control. However, there was broad agreement (93.76%) that a patient with controlled COPD shows few symptoms and no exacerbations and remains stable over time. This suggests that, in the participants’ view, a patient with a persistent absence of symptoms or exacerbations over time would probably be well controlled, but it is unclear whether, as a general rule, control can be established solely on the basis of these 2 variables. This becomes clear in statement 18, in which panelists value the importance of lung function in disease control. According to the agreement reached (69.8%), a low-risk patient must be clinically stable for 1 year to be considered controlled. However, in high-risk patients, agreement was not reached (27.96%) on the statement that stability should be maintained for 3 months for a patient to be considered controlled. Most panelists (>92%) indicated their agreement with the following criteria for adjusting treatment: adherence, physical activity, comorbidities, and patient preferences.

All statements on COPD treatable traits achieved consensus agreement. Those with the greatest degree of agreement (>91%) were those that stated that these traits should be prioritized because of their impact on prognosis, symptoms and exacerbations. It was also agreed (>75%) that the definition of treatable traits should include individual, quantifiable, and prognostic traits.

Finally, of the 14 statements on inhalation devices, 11 achieved consensus agreement and 1 consensus disagreement. Nearly 74% of panelists agreed that if the inhaler is being used properly in stable COPD, treatment outcomes depend on the lung deposition achieved by the device. However, there was consensus disagreement that if the inhalation device is used properly, there are no differences in clinical outcomes, regardless of the type of device used. Nonetheless, panelists agreed that outcomes depend on the type of inhaler, lung deposition, and the characteristics of the drug. The criterion that achieved the highest degree of consensus regarding inhaler choice was inspiratory flow (92.70%). There was no consensus with the statement that there are no differences in the outcomes obtained with nebulizers or inhalers with spacers in the management of exacerbations, regardless of their severity. It was argued that there was insufficient evidence to claim that both devices are the same in this clinical context. In fact, 67.74% agreed that nebulizers are preferable in severe exacerbations. In the absence of therapeutic response, and before escalating treatment, the main consensus (98.96%) was to check the correct use of the device. No consensus was reached for the statement that the physician should be responsible for educating patients in inhaler use. Panelists considered that the nursing staff would be more appropriate for this task.

This Delphi study highlights the concerns of panelists surrounding the challenges faced by clinicians in the care of the COPD patient. Although controversial issues still persist, the high degree of agreement reached by the panelists identifies some key messages that should be taken into account in recommendations on the management of these patients. These include the importance of therapeutic adherence, the need to define COPD control, a more personalized approach based on treatable traits, verification of proper use of inhalers before escalating treatment, and consideration of inspiratory flow as a significant criterion in the choice of inhalation device.

FundingThis study was funded by Chiesi España.

Conflict of interestJosé Luis López-Campos has received honoraria in the past 3 years for lectures, scientific consultancy, clinical trial participation, and preparation of publications from (in alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Esteve, Ferrer, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Megalabs, Menarini, Novartis, and Rovi.

Myriam Calle Rubio has received honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, and.Grifols. José Luis Izquierdo has received honoraria for consultancy, projects, and lectures from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Menarini, Novartis, Orion, Pfizer, Sandoz, and Teva.

Alberto Fernández-Villar has received in the last three years grants for research or training activities and payment for lectures or consultancy from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Esteve, Grifols, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Novartis, Roche, and Rovi.

Beatriz Abascal has given lectures and scientific consultancy sponsored by Teva, GlaxoSmithKline, Ferrer, AstraZeneca, and FAES Farma.

Bernardino Alcázar has received honoraria and/or payments in the last five years from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, FAES, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, and Novartis.

Francisco García-Río has been a speaker at activities organized by Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Novartis and Rovi; he has received grants for research projects from Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Menarini, and Esteve; and he has provided scientific consultancy to Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis.

Germán Peces-Barba has received institutional research grants from GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, and Menarini, and has provided scientific consultancy to GlaxoSmithKline and Orion Pharma.

Joan Serra Batlles has no conflict of interest.

José Javier Martínez Garcerán has given talks sponsored by Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Menarini, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Juan Antonio Riesco Miranda has no conflict of interest.

Juan Marco Figueira-Gonçalves has received speaker fees and funding for conference attendance from Esteve Laboratories, MundiPharma, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ferrer, Pfizer, FAES, Menarini, Rovi, GlaxoSmithKline, Chiesi, Novartis, and Gebro Pharma, and he has received research project grants from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Juan José Soler-Cataluña has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bial, Chiesi, Ferrer, Laboratorio Esteve, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis, Rovi and Teva; consultancy fees from Air Liquide, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, Laboratorios Esteve, Mundipharma, and Novartis, and research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Mikel Temprano has received honoraria for scientific sessions from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Francisco Ortega Ruiz has no conflict of interest.

Salud Santos Pérez has received honoraria for lectures from Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, and Novartis; and for consultancy from Almirall, Gebro Pharma, AstraZeneca, Novartis, FAES, Grifols, and Menarini.

Carlos José Álvarez Martínez has no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Fernando Sánchez Barbero PhD and Luzán 5 Health Consulting for their help in preparing the manuscript.

Please cite this article as: López-Campos JL, Calle Rubio M, Izquierdo Alonso JL, Fernández-Villar A, Abascal-Bolado B, Alcázar B, et al. Consenso sobre el diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento de la EPOC: Grupo de trabajo EPOC Forum. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:596–599.