The gold standard for the diagnosis of diffuse interstitial lung diseases (ILD) is multidisciplinary evaluation1. Lung biopsy is sometimes necessary to increase diagnostic confidence2. Transbronchial cryobiopsy (TBCB) has emerged as an alternative to surgical biopsy with lower morbidity and mortality3,4. The most common complications of cryobiopsy are pneumothorax and bleeding4,5. Although 3 cases of pulmonary cavitation following this procedure have been described, no associated cases of pneumatocele have been reported. We present a case of pneumatocele as a complication of TBCB.

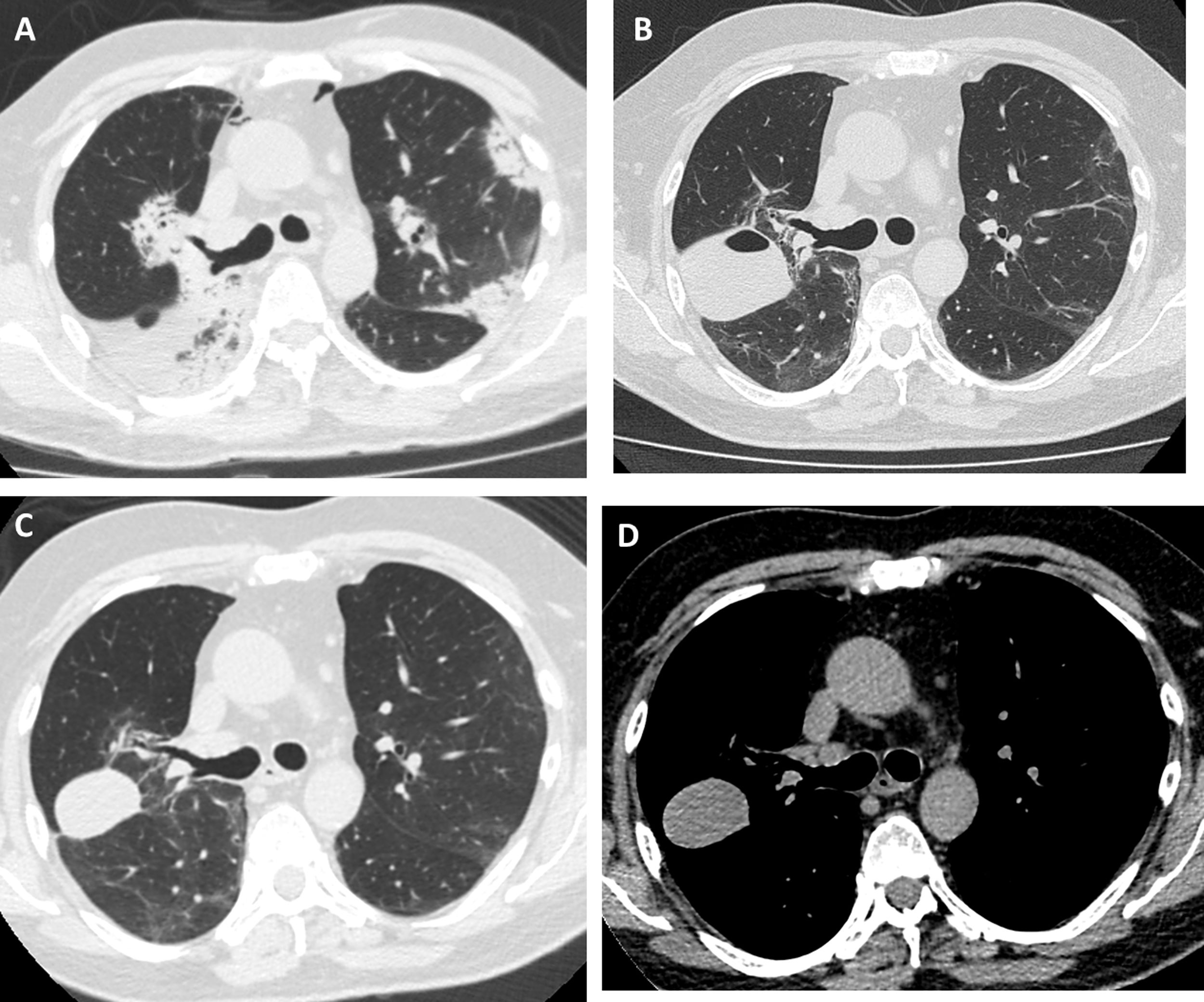

Our patient was a 55-year-old man, non-smoker, who was referred to our institution for slowly resolving pneumonia. A month earlier, he presented with cough, dyspnea, and bilateral pulmonary opacities. He received empirical antibiotic treatment with amoxicillin-sulbactam and clarithromycin, then piperacillin-tazobactam and finally vancomycin, with no clinical improvement and worsening oxygenation. On admission, he was hypoxemic with an oxygen saturation of 90% breathing room air. The analysis showed no significant results: eosinophil count within normal limits, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 34 mm/h, serology negative for HIV, ANCA and ANA normal, and CPK within normal limits. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral consolidations, predominantly peripheral, with peribronchovascular distribution and some areas with reversed halo sign (Fig. 1A). We performed bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsy using a 1.9 mm cryoprobe. Five biopsies were obtained from the right upper lobe, 3 in the posterior segment and 2 in the apical segment. The procedure was completed without complications. The pathology study showed characteristic findings of organizing pneumonia. We started treatment with prednisone at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day. The patient progressed without fever and his dyspnea improved progressively. One month after treatment, a follow-up chest X-ray showed a cavitary lesion in the upper field of the right hemithorax. A chest CT without contrast agent was performed to characterize the image, revealing a mass with smooth margins, 3 cm in diameter, in the posterior segment of the right upper lobe (Fig. 1B). The patient was asymptomatic, with normal labs and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 5 mm/h; nevertheless, we obtained a BAL specimen from the affected lung segment. Microbiological results were negative and BAL cellularity was normal. The lesion was interpreted as a pneumatocele, caused by the TBCB. We decided to take a watchful waiting approach with clinical follow-up. Two months later, the patient was asymptomatic and CT showed persistence of the cavity with a homogeneous density of 30–40 Hounsfield units, in contact with the pleura and the oblique fissure (Fig. 1C and D).

High-resolution chest tomography. (A) before TBCB: bilateral consolidations with peripheral and peribronchovascular air bronchogram. (B) 1 month after TBCB: lesion with air-fluid level in right upper lobe. (C) and (D) 3 months after TBCB: decrease in the size of the lesion with disappearance or reabsorption of the air content and persistence of the bloody content (hematocele).

The lesion was unlikely to have a neoplastic origin, given its morphology, rapid development, and reduced size on follow-up. Its appearance following TBCB and its location in one of the biopsied lung segments suggested that it was a complication of the TBCB. The absence of symptoms, laboratory test changes, and microbiological evidence in BAL, and a favorable clinical course without antibiotic treatment, further ruled out the possibility of a pulmonary abscess. Chest CT showed no pleural effusion and the pulmonary parenchyma surrounding the lesion was normal, so the hypotheses of a phantom tumor following the plane of the fissure or a pulmonary hematoma were therefore rejected. The radiological characteristics of the lesion – air-fluid cavity, thin, regular wall, with smooth margins – supported the diagnosis of pneumatocele. The density of 30–40 Hounsfield units suggested blood in the cavity6 as a secondary complication. In our opinion, the pneumatocele was the product of necrosis generated by the cryobiopsy.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of post-TBCB pneumatocele. A pneumatocele is a thin-walled, gas-filled space contained within the lung parenchyma7. It is usually solitary and transient, and sometimes contains fluid levels. Its pathogenesis has been associated with a combination of necrosis and a valvular mechanism in the airway that would allow air to enter but not exit8. The described causes of pneumatocele are pneumonia, thoracic trauma, hydrocarbon ingestion, and positive pressure ventilation9.

TBCB is increasingly used for the evaluation of ILD, and this increase may lead to new complications. Complications reported include moderate-severe bleeding (14.2%), pneumothorax (9.4%), ILD exacerbation (0.3%), death (0.3%), pneumomediastinum, arrhythmias, and lung infections5,10. There are 2 reports of cases of pulmonary abscesses11,12 and 1 of a non-infectious cavitation13, but none of the series published to date has described the appearance of pneumothorax.

In conclusion, pneumatocele is a possible complication of TBCB and should be taken into account in patients who undergo this procedure.

Please cite this article as: Castro HM, Wainstein EJ, Castro Azcurra R, Seehaus A. Neumatocele posterior a criobiopsia pulmonar. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:599–600.