Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that usually affects young patients, with an estimated incidence in Spain of 1.36/100000 inhabitants.1 The pathogenesis of sarcoidosis is thought to be related with exposure to certain environmental factors in genetically predisposed individuals.2,3 Whether or not patients with sarcoidosis have a greater risk of developing cancer is debatable,4,5 but reports in the literature of the tumor appearing before the diagnosis of sarcoidosis are rare and limited to case series. We report a series of 14 patients who were diagnosed with sarcoidosis during oncological follow-up of extrathoracic cancers.

We performed a retrospective, descriptive, observational follow-up (January 2012–June 2017) of patients with extrathoracic tumors referred to the bronchoscopy unit for the exploration of new mediastinal lymphadenopathies on a chest computed tomography (CT).

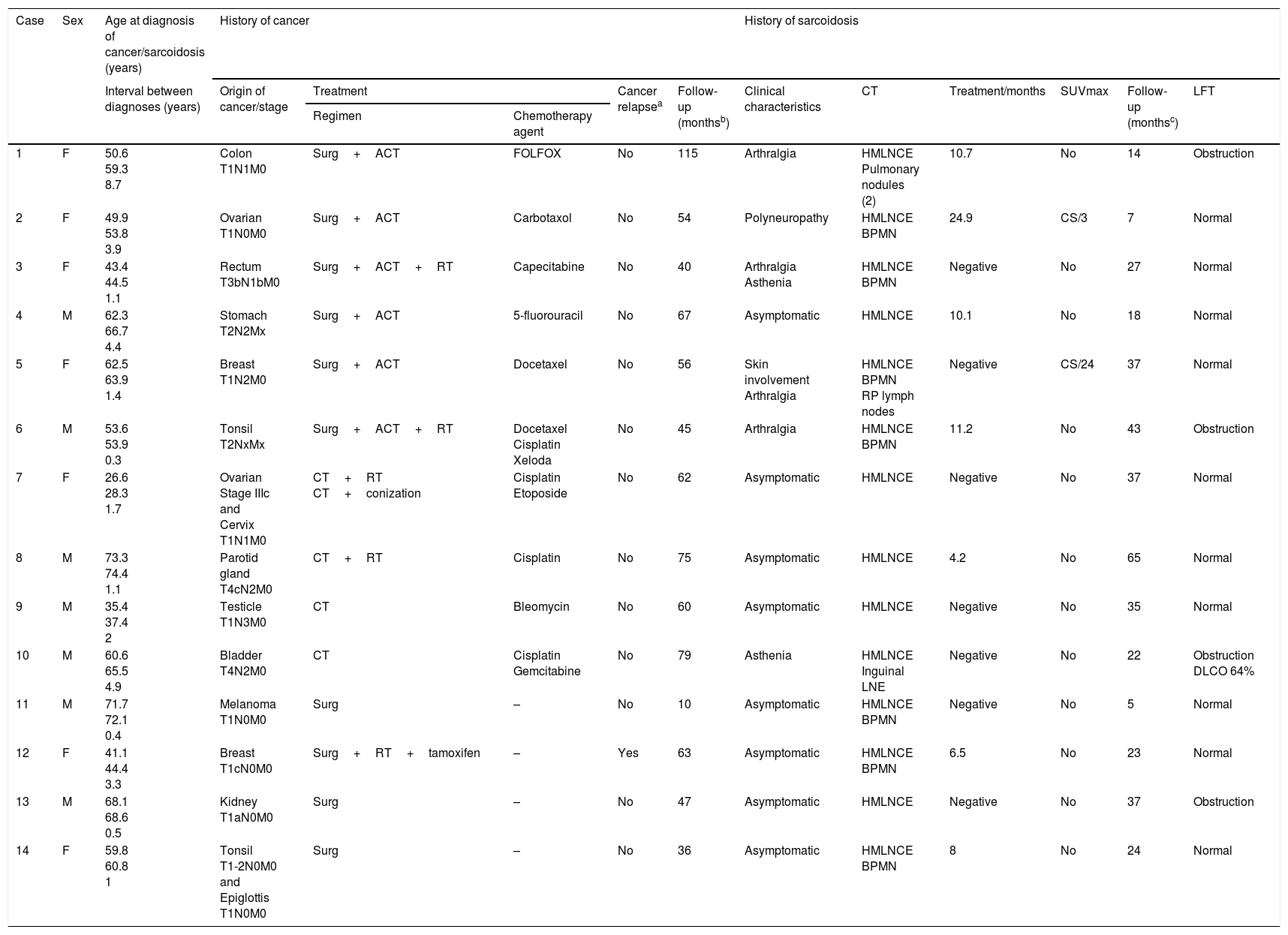

A total of 2420 patients were evaluated, of which 437 candidates met the study criteria; 404 were finally included. Reasons for exclusion were contraindication for endobronchial ultrasound for various reasons (12 cases), mediastinal lymphadenopathies already present at the time of cancer diagnosis (15 cases), or patient's refusal to perform more diagnostic tests (6 cases). All patients underwent linear endobronchial ultrasound for lymphadenopathy aspiration (Olympus BF-UC180F; Olympus ViziShot needle NA-201SX-4022, 21G) under sedation with midazolam. Fourteen patients (7 men and 7 women; mean age at diagnosis of the tumor 54.2±13.9 years) were diagnosed with sarcoidosis on the basis of clinical and radiological criteria with histological confirmation6 (mean age at sarcoidosis diagnosis: 56.6±13.7 years). Mean time between both diagnoses was 2.4±2.3 years. The most common tumors were gastrointestinal (three cases), breast, gynecological, and oropharyngeal (two each) (Table 1). Two patients had two tumors (cervical-ovarian and epiglottal-tonsillar; interval between diagnoses 36 and 4 months, respectively). Most tumors were diagnosed in early stages [stages I–II; 12/16 (75%); stage III: 3/16 (18.8%); stage IV: 1/16 (6.2%)]. The stations most often aspirated were the subcarinal (7; 100%) and lower right paratracheal [4R; 9/14 (64.3%)]. Eight patients (57.1%) had sarcoidosis at radiological stage II and six patients presented stage I (42.9%). Eight of the 14 patients (57.1%) were asymptomatic, 4 (28.6%) had arthralgia, 2 (14.3%) had asthenia, 1 (7.1%) had polyneuropathy, and another (7.1%) had skin involvement. In all cases, cultures to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis in lymphadenopathy samples were negative. In addition to bilateral enlargement of the mediastinal lymph node chains, seven patients (50%) had diffuse bilateral millimetric pulmonary nodules. Increased mediastinal uptake on positron emission tomography was observed in 7 of the 14 patients (SUVmax 16.2±12.9; range 4.2–24.9). Only 10 of the 14 patients received chemotherapy (four cisplatin and two docetaxel) (Table 1). Two patients were treated with corticosteroids (those with polyneuropathy and skin involvement) for 3 and 24 months (maximum doses of 50 and 30mg prednisone, respectively). Response was favorable in both cases. Mean patient follow-up was 57.8±24.1 months after diagnosis of the tumor (with only one tumor relapse and no deaths), and 28.1±15.8 months after the sarcoidosis diagnosis.

Characteristics of the 14 patients.

| Case | Sex | Age at diagnosis of cancer/sarcoidosis (years) | History of cancer | History of sarcoidosis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval between diagnoses (years) | Origin of cancer/stage | Treatment | Cancer relapsea | Follow-up (monthsb) | Clinical characteristics | CT | Treatment/months | SUVmax | Follow-up (monthsc) | LFT | |||

| Regimen | Chemotherapy agent | ||||||||||||

| 1 | F | 50.6 59.3 8.7 | Colon T1N1M0 | Surg+ACT | FOLFOX | No | 115 | Arthralgia | HMLNCE Pulmonary nodules (2) | 10.7 | No | 14 | Obstruction |

| 2 | F | 49.9 53.8 3.9 | Ovarian T1N0M0 | Surg+ACT | Carbotaxol | No | 54 | Polyneuropathy | HMLNCE BPMN | 24.9 | CS/3 | 7 | Normal |

| 3 | F | 43.4 44.5 1.1 | Rectum T3bN1bM0 | Surg+ACT+RT | Capecitabine | No | 40 | Arthralgia Asthenia | HMLNCE BPMN | Negative | No | 27 | Normal |

| 4 | M | 62.3 66.7 4.4 | Stomach T2N2Mx | Surg+ACT | 5-fluorouracil | No | 67 | Asymptomatic | HMLNCE | 10.1 | No | 18 | Normal |

| 5 | F | 62.5 63.9 1.4 | Breast T1N2M0 | Surg+ACT | Docetaxel | No | 56 | Skin involvement Arthralgia | HMLNCE BPMN RP lymph nodes | Negative | CS/24 | 37 | Normal |

| 6 | M | 53.6 53.9 0.3 | Tonsil T2NxMx | Surg+ACT+RT | Docetaxel Cisplatin Xeloda | No | 45 | Arthralgia | HMLNCE BPMN | 11.2 | No | 43 | Obstruction |

| 7 | F | 26.6 28.3 1.7 | Ovarian Stage IIIc and Cervix T1N1M0 | CT+RT CT+conization | Cisplatin Etoposide | No | 62 | Asymptomatic | HMLNCE | Negative | No | 37 | Normal |

| 8 | M | 73.3 74.4 1.1 | Parotid gland T4cN2M0 | CT+RT | Cisplatin | No | 75 | Asymptomatic | HMLNCE | 4.2 | No | 65 | Normal |

| 9 | M | 35.4 37.4 2 | Testicle T1N3M0 | CT | Bleomycin | No | 60 | Asymptomatic | HMLNCE | Negative | No | 35 | Normal |

| 10 | M | 60.6 65.5 4.9 | Bladder T4N2M0 | CT | Cisplatin Gemcitabine | No | 79 | Asthenia | HMLNCE Inguinal LNE | Negative | No | 22 | Obstruction DLCO 64% |

| 11 | M | 71.7 72.1 0.4 | Melanoma T1N0M0 | Surg | – | No | 10 | Asymptomatic | HMLNCE BPMN | Negative | No | 5 | Normal |

| 12 | F | 41.1 44.4 3.3 | Breast T1cN0M0 | Surg+RT+tamoxifen | – | Yes | 63 | Asymptomatic | HMLNCE BPMN | 6.5 | No | 23 | Normal |

| 13 | M | 68.1 68.6 0.5 | Kidney T1aN0M0 | Surg | – | No | 47 | Asymptomatic | HMLNCE | Negative | No | 37 | Obstruction |

| 14 | F | 59.8 60.8 1 | Tonsil T1-2N0M0 and Epiglottis T1N0M0 | Surg | – | No | 36 | Asymptomatic | HMLNCE BPMN | 8 | No | 24 | Normal |

ACT, adjuvant chemotherapy; BPMN, bilateral pulmonary micronodules; CS, corticosteroids; CT, chemotherapy; F, female; HMLNCE, hilar-mediastinal lymph node change enlargement; LFT, lung function tests; LNE, lymph node enlargement; M, male; RP, retroperitoneal; RT, radiation therapy; Surg, surgery; SUVmax, standardized maximum uptake value on positron emission tomography.

This study shows that the development of new mediastinal lymphadenopathies in a cancer patient does not necessarily mean tumor extension, even if hyperenhancement is observed, and the possibility of sarcoidosis (or other diseases) must be considered.7 Histological confirmation is always needed.8 Another important finding is that the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was always subsequent to the tumor diagnosis. The inverse order has been described more often, and very few published series report a diagnostic chronology of tumor followed by sarcoidosis.9,10

It is sometimes difficult to differentiate between sarcoidosis, tuberculosis or a sarcoid-like reaction. The diagnosis of tuberculosis, a real possibility in our region which has an incidence of 21.3 cases/100000 inhabitants/year,11 was ruled out in all cases by a negative culture for M. tuberculosis in a sample of mediastinal lymphadenopathy obtained by endobronchial ultrasound. A sarcoid-like reaction (development of non-caseifying epithelioid cell granulomas in patients who do not fully meet the criteria for sarcoidosis) can occur in cancer patients in the first regional lymph node chain to which a particular tumor might metastasize, taking into account the strategic position occupied by each nodal group.12,13 This phenomenon is more common in testicular cancers and lymphomas. As mediastinal lymphadenopathies would be the first chains to which lung and pleural cancers would metastasize, these tumors were excluded from the study. Moreover, the fact that our patients were in remission, yet presented systemic symptoms or mediastinal lymphadenopathies with uptake on PET7 (six and seven of our patients, respectively), was suggestive of a diagnosis of sarcoidosis. However, even with these differentiating factors, it may be difficult to distinguish between these two entities.

Although the association between cancer and sarcoidosis was formerly believed to be incidental, the current thinking is that certain etiopathogenic mechanisms may be involved in genetically predisposed individuals, such as immune hyperresponsiveness of the host to the cancer itself (or antigens produced by the tumor),9 or the treatment of the tumor itself,12 as in the case of nivolumab in metastatic melanoma.13

The main limitation of this study is that we may have generated some bias by limiting inclusion to patients referred to a bronchoscopy unit, as this procedure might not be requested in all patients, metastasis of the underlying tumor perhaps being assumed in many cases.

In conclusion, the appearance of mediastinal lymphadenopathies in patients with extrapulmonary tumors should not be assumed to be tumor recurrence, and other causes, including sarcoidosis, must be considered. Histological diagnosis is the technique of choice in these cases. Although the relationship between cancer and sarcoidosis and the pathogenic mechanisms that might link them have not been clearly established, either the tumor itself or else the anticancer treatment may possibly promote the development of sarcoidosis in genetically predisposed individuals. More studies are needed to clarify this association and its clinical value and prognosis.

Please cite this article as: Pereiro T, Golpe A, Lourido T, Valdés L. Tumores extrapulmonares y sarcoidosis. ¿Relación casual o real? Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:531–533.