Eosinophilic pleural effusion (EPE) is pleural effusion (PE) in which eosinophils account for more than 10% of pleural fluid (PF) cellularity. In published series on PE, about 7.5% of the population show EPE.1,2 The most common overall cause of EPE is air or blood in the pleural space and the most common known etiology is malignant disease. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (IHES) is a heterogeneous group of disorders consisting of hypereosinophilia, defined as an absolute eosinophil count >1.5×109/l or >1500cells/μl in 2 consecutive samples obtained 1 month apart, combined with eosinophil-induced organ damage, when other causes of hypereosinophilia have been excluded.

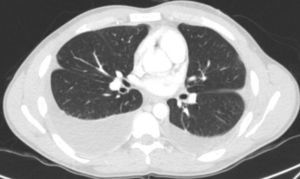

We report the case of a 25-year-old man with bilateral PE (Fig. 1). Complete blood count showed eosinophil concentrations of 3500/mm3, representing 26% of total white blood cells. He had shown similar results on previous tests. PF initially had a turbid appearance, with characteristics of exudate, glucose levels of 64mg/dl and adenosine deaminase levels of 27.7U/l. PF cytology showed no malignant cells and acutely predominant inflammatory cells, with abundant eosinophils (50%–60% of total cell count). PF culture was negative for bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. Echocardiography showed neither pericardial effusion nor infiltrative cardiomyopathy. Tests were performed to rule out secondary causes of hypereosinophilia, all of which were negative, and after comprehensive hematological studies, the diagnosis was IHES. Response to prednisone 1mg/kg was favorable. The eosinophilia abated initially in peripheral blood and subsequently, after 7 months, in PE. Eosinophil levels in normal PF are low (less than 1%). High levels can be due to multiple causes. The most common causes of EPE are malignant (around 30%–34%1,2), parapneumonic, and tuberculous effusion. Other possible etiologies include asbestos, drug toxicities, parasitical infections, and Churg-Strauss syndrome, or less commonly, viral infections and pulmonary embolism.3 Very little information is available on EPE due to IHES or causes other than those mentioned, as can be surmised from the few cases reported to date.4 The particular interest in this patient is that the disease started only as relapsing EPE. In one of the published cases, the patient had hepatosplenomegaly and ascites combined with bilateral PE, and unlike our patient, the outcome was death. In addition to bilateral EPE, the other patient presented skin lesions which were found to be due to vasculitis.5

When EPE with no apparent etiology is observed, IHES must be considered. Eosinophilia in peripheral blood in the absence of other manifestations should alert to the presence of this entity. Close collaboration with the hematologist is necessary to confirm the etiology of this finding.

Please cite this article as: Lima Álvarez J, Peña Griñán N, Simón Pilo I. Derrame pleural eosinofílico secundario a síndrome hipereosinofílico idiopático. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:538.