Unlike the situation in other countries, mucosal involvement of the airway in tuberculosis is very rare in developed countries.1 In series of Asian patients, endotracheal involvement is reported in a small percentage of patients with endobronchial disease2; however, we found no descriptions of this presentation by Spanish authors (PubMed search, terms: endotracheal tuberculosis or tracheal tuberculosis and Spain). No endotracheal disease was reported in any of the 73 cases of tuberculosis with endobronchial disease included in the largest Spanish series.3 It has been suggested that airway involvement in tuberculosis is caused by the presence of a heavy endobronchial bacterial load.4 Indeed, in the series of Jung et al., 232 of 233 patients with endobronchial disease had a positive direct sputum smear.2

However, we report a case of tracheal involvement in tuberculosis with some exceptional features: the patient did not have other endobronchial lesions, and the sputum smear stains before bronchoscopy were negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

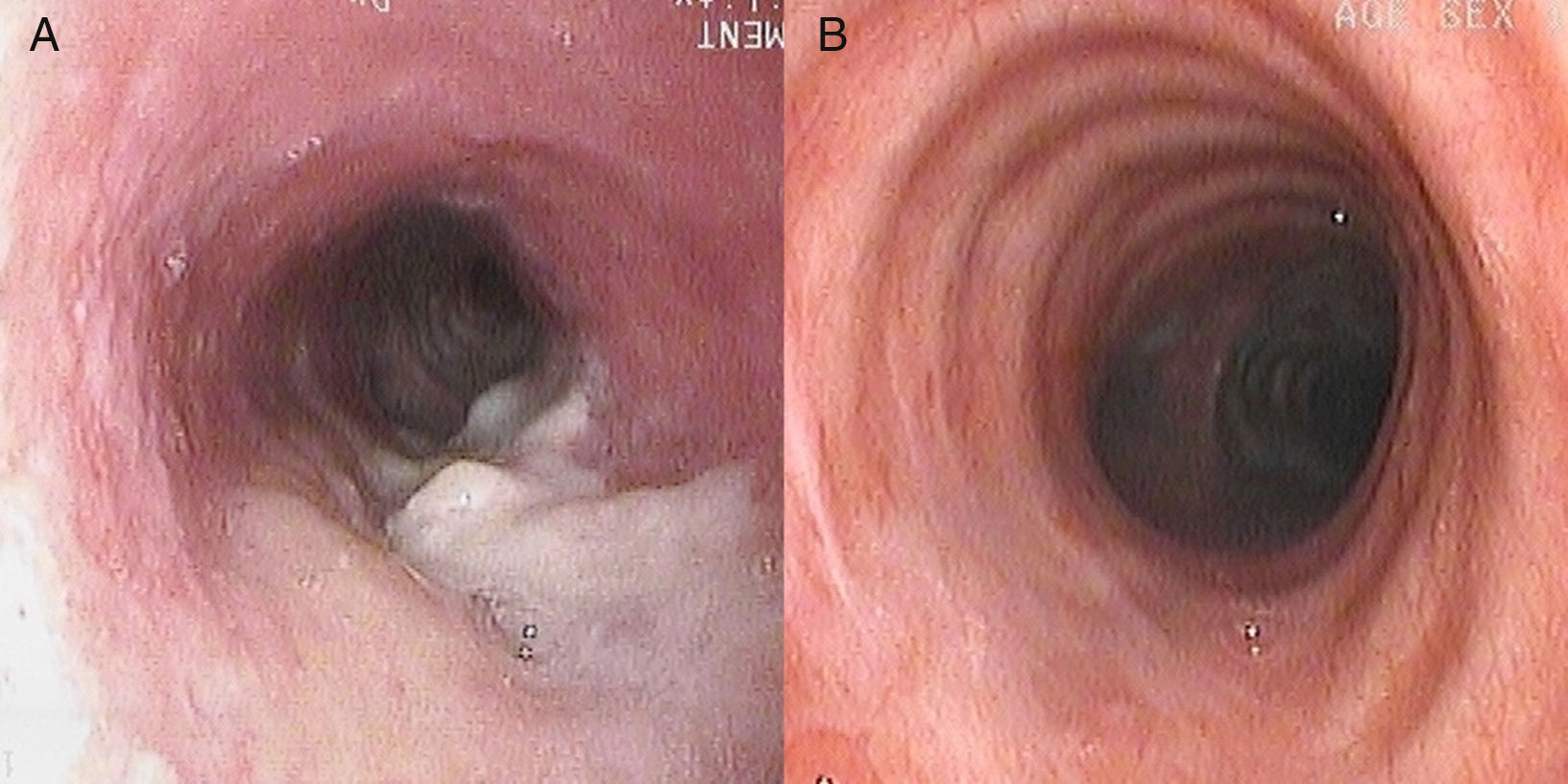

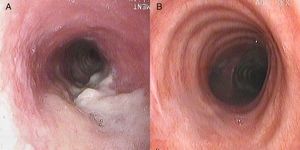

A 49-year-old women of Spanish nationality was referred to our clinic with a 1-year history of cough with scant expectoration, dysphonia, recurrent episodes of low-grade fever, and poor response to different antibiotic regimens. She was a former smoker of 10 pack-years with no other history of interest. Lung function tests were normal and chest high-resolution computed tomography revealed bronchiectasis in the apical segments of both lower lobes and in the right upper lobe, tree-in-bud infiltrates, and thickening of the posterior tracheal wall with no hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathies. Sputum smears were negative and a bronchoscopy was performed which showed a raised lesion of necrotic appearance in the posterior wall of the middle third of the trachea, with mucosa of a granular appearance in the circumference (Fig. 1A). The mucosa in the rest of the bronchial tree was of normal appearance. Ziehl-Neelsen staining was negative in bronchial aspiration material and bronchoalveolar lavage, but, in contrast, the PCR was positive for Mycobacterium complex. Acid alcohol-fast bacilli were observed in sputum collected after the endoscopic exploration and necrotizing granulomas were seen in the biopsy. After antituberculosis treatment, complete resolution of the tracheal lesions was observed (Fig. 1B).

The incidence of endotracheal tuberculosis is difficult to establish since in many cases bronchoscopy is not considered necessary for diagnosis.3 A review of the literature revealed no descriptions of tracheal tuberculosis in Spain.3,5 However, it is not unusual in Asian countries.2,6 In a prospective study of 429 patients with tuberculosis who underwent bronchoscopy, Jung et al. found bronchial disease in up to 50% and tracheal disease in 16% of the cases.2 As in our case, it occurs more frequently in women. The predominance of the female sex has been attributed to prolonged exposure to bacilli, due in part to the narrowness of the airways.2,7

Although most patients with tracheobronchial tuberculosis improve with correct treatment, up to 20% of cases have been associated with the development of tracheobronchial stenosis.2,7,8 In Spain, however, the origin of the involvement was not attributed to tuberculosis in any of the cases included in a series of 136 patients treated for central airways stenosis.5

In conclusion, tracheobronchial tuberculosis is an entity which should be considered in cases of tuberculosis, taking into account the importance of the role of bronchoscopy in its identification, particularly in women with prolonged symptoms. Establishing a diagnosis and early treatment can be crucial to prevent the development of complications.

We thank Eduardo García Pachón for his ideas and collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Soler-Sempere MJ, Berenguer-Díez MA, Padilla-Navas I. Tuberculosis endotraqueal en una paciente no bacilífera. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:592–593.