Tuberculosis (TB) still has an annual incidence in Spain of 18.2/100,000 inhabitants.1 We report a case of endobronchial tuberculosis with lymph node and skin involvement, an unusual form in our setting.

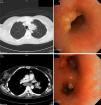

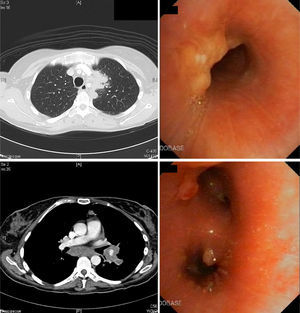

A 45-year-old woman who had been resident in India until 8 months previously, presented with clinical symptoms for the last 3 months of daily fever (up to 38°C), anorexia, weight loss, dry cough, and dyspnea that did not improve after 7 days of treatment with amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. She had good general health upon examination, the only remarkable finding being two mobile, rubbery subcutaneous nodules sized 1cm in the left upper quadrant that were slightly painful but with no signs of inflammation, and a similar one in the left hand. Blood tests revealed anemia, leukocytosis and thrombocytosis. Chest radiography showed a mass in the anterior mediastinum described in the computed tomography (CT) report as “mass in the left upper lobe and ipsilateral hilar region, with anterior mediastinal infiltration causing stenosis of the bronchial lumen; ipsilateral subcarinal and paratracheal lymphadenopathies, accompanied by multiple independent nodules in the left lung, pleural implants, and subcutaneous abdominal nodules”. Bronchoscopy revealed inflamed mucosa with implants of tumor-like appearance and left bronchial stenosis. Malignancy was ruled out after biopsy, but both bronchial biopsies and one of the abdominal nodes showed non-necrotizing granulomas. Cultures were initially negative, but then multi-susceptible Mycobacterium tuberculosis grew in sputum. Accordingly, the patient was diagnosed with disseminated TB with tumor-type endobronchial and skin involvement. The patient improved rapidly with TB therapy and corticosteroids. Bronchoscopy was normal at 6 months, while the CT showed only residual thickening of soft tissues (Fig. 1).

Endobronchial TB occurs in 5%–40% of active pulmonary TB, although it is underdiagnosed.2,3 The cause is implantation directly from an adjacent cavity, a focus of tuberculosis or a mediastinal lymph node, or by bloodborne or lymphatic spread.3,4 Symptoms include cough (71%–100%), fever (50%), weight loss (30%), hemoptysis (18%–25%), dyspnea, chest pain and anorexia.2,4,5 Both the duration of symptoms and the disease progression are variable and can range from complete resolution to the appearance of bronchiectasis, bronchial obstruction or atelectasis. The most useful microbiological test is bronchoalveolar lavage, which outperforms sputum.2–5 X-ray may show alveolar infiltrates (35%–43%), nodules (25%), cavitated lesions (12%), pleural effusion (9%) or hilar thickening (7%), but it may be normal in 10%–20% of cases.2,3 CT is useful for assessment of disease extension, degree of bronchial obstruction and progress, and may replace bronchoscopy during follow-up,4 although it is the imaging study of choice during diagnosis.

Chung and Lee classify TB into seven subtypes3: caseating (12%–43%), edematous-hyperemic (14%–44%), fibrostenotic (6%–10.5%), tumoral (10.5%–30%),3–5 granular, ulcerative, and nonspecific bronchitis type. The first four have a poorer prognosis, because of associated bronchial stenosis.3 These types seem to represent different stages of the same disease, starting with granulomas and submucosal inflammatory lesions that progress to masses, fibrosis and airway stenosis.4,5 The tumoral subtype has endobronchial masses, with a hemorrhagic surface and a necrotic outer layer, simulating squamous carcinoma. Risk factors for residual bronchial stenosis are age over 45 years, fibrostenotic type, and late diagnosis.2,5 Treatment includes endoscopic dilation, mechanical resection, or stenting combined with corticosteroids. The latter seems to be effective in the early stages and the caseating/tumoral forms,4 so for this reason they were used in our patient, who achieved total recovery.

In the presence of fever and endobronchial lesions or pulmonary mass, consideration of TB at diagnosis is mandatory, especially in immigrants during the early years after arrival.

Please cite this article as: Cadiñanos Loidi J, Abad Pérez D, de Miguel Buckley R. Tuberculosis endobronquial como simulador de cáncer de pulmón. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:126–127.