Empyema necessitatis is a rare complication that can occur when pleural infections are treated late or inadequately. It consists of the penetration of pus from the pleural cavity through the adjacent tissues to form an abscess in the chest wall, sometimes even forming a skin fistula.1 Chest trauma is a very rare cause of empyema necessitatis, so a case recently treated at our center is of interest.

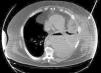

A morbidly obese 49-year-old male, current smoker, with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus type 2, presented due to left costal blunt trauma caused by an impact from the horn lateral surface of a charging bull, 30 days before his admission to the hospital. The patient did not attend emergency services at the time of trauma. He had a hematoma in the left chest wall and chest pain, which did not improve with standard analgesia. On arrival to the emergency room, blood pressure was 140/86mmHg, heart rate 110bpm, oxygen saturation 96%, and temperature 36.5°C. Physical examination revealed a hematoma in left lateral chest wall with no surrounding cellulitis and decreased breath sounds in the left hemithorax. Blood tests showed leukocytosis of 32,400/mm3 with neutrophilia (92.2%), hemoglobin 10g/dl, glucose 487mg/dl, and C-reactive protein 40.3mg/dl. Left pleural effusion was detected on the chest X-ray and no rib fractures were observed. A computed tomography (CT) scan completed the study, revealing left pleural effusion that connected with a collection in the left anterolateral chest wall (Fig. 1). Empiric antibiotic therapy with piperacillin-tazobactam was initiated (4/0.5mg IV every 8h) and both collections were drained by percutaneous puncture of the chest wall and a chest tube, from which abundant purulent material was obtained. Good lung re-expansion was observed on X-ray. After 72h of admission, multiple orifices were observed in the left lateral thoracic wall, surrounded by purulent necrotic areas without muscle involvement, so debridement and lavage were performed under general anesthesia. Microbiological results from both the pleural fluid and thoracic abscess were positive for Streptococcus agalactiae, that was sensitive to the prescribed antibiotic. The patient was hospitalized for 40 days, during which surgical wound care continued without the need for additional interventions.

The most common location of an empyema necessitatis is, as in this case, the anterior chest wall between the midclavicular and anterior axillary line. Other locations less frequently described are the abdominal wall, the paravertebral space, the mediastinum, the breast or the diaphragm.1,2 Before the antibiotic era, most cases were caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the mortality rate was 66%. The incidence has fallen significantly since antibiotics were introduced, and the most common etiologic agents have become Actinomyces israelii, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas cepacia.3,4 In our case, the causative agent was Streptococcus agalactiae, occurring secondary to chest trauma, features that are both rare in these circumstances. The clinical presentation can vary widely and includes chest pain, soft tissue mass, cough or dyspnea. Depending on the age of the patient and his/her morbidity, it may progress to septic shock. Our case was an obese patient with poorly controlled diabetes. Both of these conditions are favorable for the development of infections with atypical etiologies and locations, due to changes in the immune system response to invading microorganisms, principally fungi and bacteria. Diagnosis is based on imaging techniques, mainly CT, revealing the continuity between the pleural collection and the abscess in the chest wall. The differential diagnosis must consider other diseases such as lymphoma, mesothelioma or endocarditis.4 Although treatment should be tailored for each patient, both antibiogram-adjusted antibiotic treatment, when possible, and surgical drainage are crucial. Drainage is required to evacuate the accumulated pus and to sterilize and close the pleural cavity, thus allowing good pulmonary mobility. Different procedures may be employed, such as closed drainage systems by tube thoracostomy, or partial costectomy, or open systems, such as open thoracostomy with the creation of a pleurocutaneous fistula that allows drainage without a tube. The timing of these treatments is not standardized, but the intravenous antibiotic should be maintained for a week and then oral treatment should be continued for 1–3 weeks, depending on the patient's clinical response.5 With the combination of both treatments, a high cure rate is achieved with a low mortality rate (less than 5%); death, if it occurs, is usually secondary to the confluence of several mechanisms. such as respiratory failure, heart failure, mediastinitis, hematogenous spread or renal failure.1

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Bru S, Martínez-Ramos D, Salvador-Sanchís JL. Empiema necessitatis tras traumatismo torácico. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:82–83.