The fact that the first symptom of a primary tumor is bone metastasis is not uncommon and should be part of the differential diagnosis in patients with history of risk. Lung cancer has a predilection for bones, and metastases generally settle in the proximal femur.

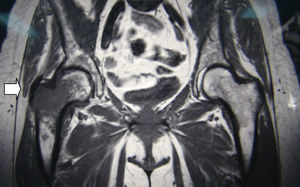

We present the case report of a 56-year-old woman, with no personal history of interest other than being a pack-a-day smoker, who came to our consultation due to pain in the trochanteric region that had been evolving over the past 2 months. It was treated as trochanteric bursitis, with poor response to non-steroid anti-inflammatory medication. Given the lack of improvement and poor-quality radiographies, magnetic resonance imaging tests (MRI) were ordered, which revealed a central, expansive image with aggressive characteristics located at the major trochanter of the right hip (Fig. 1). With the suspicion of primary or metastatic malignant tumor, an extension study was done with thoraco-abdominal computed tomography, which revealed a left suprahilar lung mass measuring 20×23mm that infiltrated the aortopulmonary window, with homolateral mediastinal lymphadenopathies and an osteolytic image in the right intertrochanteric femoral neck, measuring 45mm with soft tissue mass. Bronchoscopy demonstrated inflammatory mucosa in the left upper lobe. Bronchial aspiration with no neoplastic cells. PET/CT: left perihilar mass 20×25mm (SUV 16), lytic lesion with soft tissue mass in the trochanteric area of the right femur (SUV 8.7). Analysis: hemogram, 3750 leukocytes; hemoglobin, 8.5g/dl; platelets, 164,000. Biochemistry: albumin, 3g/dl; alkaline phosphatase, 113U; lactate dehydrogenase, 130U; the remainder was normal. Ions and coagulation, normal. Carcinoembryonic antigen, 127ng/ml; Ca15.3, 37U/ml; Ca 125 and Ca 19.9, normal. We carried out percutaneous biopsy of the trochanteric region, guided by radioscopy, which was reported to be compatible with metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma.

With said diagnosis, and given the immobility of the patient, we opted for complete resection of the trochanteric metastasis and substitution of the defect by implanting a megaprosthesis. Post-op was adequate, and the patient was up and walking on the 5th day with a walker, and with the use of a cane one month later.

EvolutionSystemic chemotherapy was begun with cisplatin and vinorelbine, competing 6 cycles with no incidences and an acceptable quality of life for the patient. After 7 months, the patient was hospitalized due to a process of deterioration and disorientation, and cerebral MRI diagnosed cerebral metastases. Holocranial radiotherapy was begun, but one month later the patient started to have generalized bone pain, dysphagia and progressive dyspnea secondary to the progression of the disease in the lungs and mediastinum. The patient died 13 months after the diagnosis.

DiscussionIt is important to include tumor pathology within the differential diagnoses of muscular-skeletal pain, especially in patients who have risk factors like smoking.1 Clinically, it is difficult to diagnose primary bone tumor or metastasis, but it should be suspected when the pain is continuous, even at rest, and there is no improvement with analgesic therapy. When given pain with these characteristics, simple radiography should be taken of the affected region, as it is a test that provides much information. At middle age, and mainly over the age of 60, the differential diagnosis initially includes a metastatic origin, and then a primary tumor such as giant-cell tumor or osteosarcoma. Among the lung tumor types, non-small-cell lung cancer most frequently presents bone metastasis, most of which (66%) are detected at the time of the initial diagnosis.2 When these lesions are metastatic, their management varies depending on possibilities for survival. Even though the prognosis is very poor, surgery of the area, especially if the hip is involved, provides the patient with much better mobility and a high quality of life. The best surgical option is complete resection of the metastasis, especially when it is a single metastasis, and substitution of the bone defect by implanting a megaprosthesis. The components are generally cemented for fast bone incorporation and to be able to rapidly make the patient mobile.3,4

FundingThe authors declare having received no source of funding.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare having no conflict of interests regarding this paper.

Please cite this article as: Puertas García-Sandoval JP, et al. Diagnóstico de adenocarcinoma pulmonar por metástasis ósea en cadera. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;49:37–8.