In February 2011, a 53-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for fever, non-productive cough and dyspnea on effort; he did not report any history of workplace exposure during the medical examination.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed bilateral pulmonary consolidations, mainly involving the lower lobes.

No leukocytosis was seen on the blood tests, and the differential leukocyte count was 72.7% neutrophils and 18.5% lymphocytes. Serum biochemistry results were normal. Tests for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-DNA antibodies and extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) were negative.

Arterial blood gases (ABG) showed moderate hypoxemia, with partial oxygen pressure (PO2) 52mmHg, PCO2 34mmHg, and pH 7.48; arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) was 88%.

Pharyngeal swab analysis was positive for H1N1.

The patient was referred to the infectious diseases unit, where he received combined treatment with prednisone 25mg, orally, twice a day for 10 days, cefotaxime 1g, intravenously, twice a day for 10 days, inhaled zanamivir (2mg×5mg) twice a day for 5 days and oseltamir, 1 75mg capsule twice a day for 5 days. The patient's clinical situation improved rapidly, as reflected in radiological and ABG results. Twenty days later, he was discharged in good condition.

A chest CT was performed before discharge, showing good recovery of lung function, and ABG results were normal (pH=7.41; PCO2=37mmHg; PO2=85mmHg and SaO2=96%).

The patient was then referred for respiratory follow-up, including high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans, ABG analysis and lung function testing with determination of the diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO).

At the 1, 3 and 6-month follow-up visits, the patient was asymptomatic; serial chest HRCTs showed slight basal consolidation, less than 3cm in diameter, in the form of reticular and ground glass opacities.

During this time, the radiological signs did not alter either in shape or in size. Lung function test results were normal: FVC=86.6%; FEV1=96%; FEV1/FVC: 88.47; DLCO: 78% and SpO2: 96%.

In May 2012, the patient became symptomatic again, with non-productive cough and dyspnea on effort. He returned to the clinic with marked reduction in lung function parameters: FVC=66.7%; FEV1=76.2%; FEV1/FVC=90.63, SpO2=91%; DLCO values were also severely reduced (55% compared to 78%).

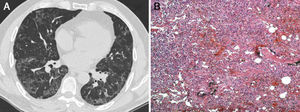

Another chest HRCT was then performed, revealing ground glass and peripheral reticular opacity, particularly in the lung bases (Fig. 1A).

(A) Chest high-resolution computed tomography showing ground glass and peripheral reticular opacities, particularly evident in the lung bases. (B) Histopathological examination revealed the following: widened alveolar septa with type II pneumocyte proliferation and inflammatory mononuclear infiltrate with interstitial fibrosis in a patchwork pattern, suggesting usual interstitial pneumonia (hematoxylin-eosin staining, original magnification 100×).

Blood and serum test results were normal. A flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed, and a transbronchial biopsy was obtained, the results of which were indecisive—only inflammatory lymphocyte infiltration and alveolar septal fibrosclerosis were found on histopathology examination. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) results were negative.

A surgical lung biopsy was performed using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) under general anesthesia with one-lung ventilation, and 3-port incision in the right side (one sample per lobe).

Histopathological analysis revealed widened alveolar septa with type II pneumocyte proliferation and mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate with interstitial fibrosis in patchwork pattern, suggesting usual interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 1B). After an incident-free post-operative period, the patient was referred to the pulmonology unit for appropriate medical treatment.

Although the etiology of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is unknown, the following risk factors have been proposed: acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), environmental exposure to metal dust, smoking habit, connective tissue disorders, drug toxicity, chronic viral infections, such as Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus (HHV)-7 and HHV-8.1

Ground glass opacity on chest imaging studies and reduced DLCO have been reported in H1N1 pneumonia in a study with 3 months’ follow-up.2,3 We report a very uncommon case of late-onset UIP after uncomplicated H1N1 pneumonia in a 53-year-old man, detected in HRCT obtained one year after the disease onset.

These results, along with the histopathology examination, were consistent with the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary fibrosis may occur after ARDS or ventilator-associated pneumonia.4,5

In our patient, radiological signs of fibrosis were confirmed by histopathological examination of surgical biopsy specimens obtained by standard VATS.6

By presenting this case, we wish to draw attention to long-term sequelae in a patient with no prior history of ARDS and who did not require mechanical ventilation. Symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis with a UIP pattern on HRCT and histopathological signs were detected one year after an influenza-like infection, but otherwise, the patient was a healthy adult who did not present any of the comorbidities usually associated with influenza.

Several cases of ARDS subsequent to H1N1 have been described in the literature,4–6 but this is the first report of a correlation between H1N1 and UIP, and we believe this to be the unique feature of our case.

Please cite this article as: Baietto G, Davoli F, Turello D, Rena O, Roncon A, Papalia E, et al. Fibrosis pulmonar tardía (neumonía intersticial usual) en un paciente con antecedentes de neumonía asociada a H1N1 no complicada. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:363–364.