Tuberculosis risk is increased in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases receiving any immunosuppressive treatment, notably tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists therapy. Screening for the presence of latent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and targeted preventive treatment to reduce the risk of progression to tuberculosis disease is mandatory in these patients.

This Consensus Document summarizes the current knowledge and expert opinion of biologic therapies, including TNF-blocking treatments. It provides recommendations for the use of interferon-gamma release assays (IGRA) and tuberculin skin test (TST) for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in these patients, and for the type and duration of preventive therapy.

El riesgo de enfermar de tuberculosis ha aumentado en los pacientes con enfermedades inflamatorias crónicas que reciben tratamiento inmunosupresor, en particular en aquellos tratados con terapia anti-TNF (del inglés tumor necrosis factor). En estos pacientes es obligatoria la detección de la infección tuberculosa latente y el tratamiento de dicha infección, dirigido a reducir el riesgo de progresión a enfermedad tuberculosa.

Este documento de consenso resume la opinión de expertos y los conocimientos actuales sobre tratamientos biológicos, incluidos los bloqueantes del TNF. Se establecen recomendaciones para la utilización de las técnicas de liberación de interferón-gamma (IGRA) y la prueba de la tuberculina (PT) para el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de la infección tuberculosa latente.

The development of biological therapies in the last decade has meant a definitive change in the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases, which include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), Crohn's disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, among others. In 1998, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)1 approved the use of infliximab in patients resistant to conventional immunomodulatory treatment. Since then, more than 20 new drugs have been marketed for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID), in which tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and TNF receptors play a key role in the immune response during acute and chronic inflammation processes.2

Pharmacovigilance of the first authorized biological agents (infliximab and etanercept) rapidly highlighted the emergence of cases of associated tuberculosis (TB).3–5

Several studies have shown that the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) in patients and its preventive treatment with isoniazid (INH) for 9 months reduce the likelihood of progression to active tuberculosis.6,7 However, given that cases continue to be observed even after preventive treatment with INH, protocols must be reviewed and improvements in the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tests sought to improve the therapeutic approach to the IMID pacients.8

Rationale and Aims of the DocumentA wealth of new information on biological therapies available for patients with IMID has emerged. This, together with a lack of guidelines from different Spanish scientific societies, justifies the publication of a consensus document based on scientific evidence and endorsed by a group of experts that can update existing information and previous recommendations. One of the main objectives of this document is to facilitate the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with LTBI who are candidates for biological therapies.

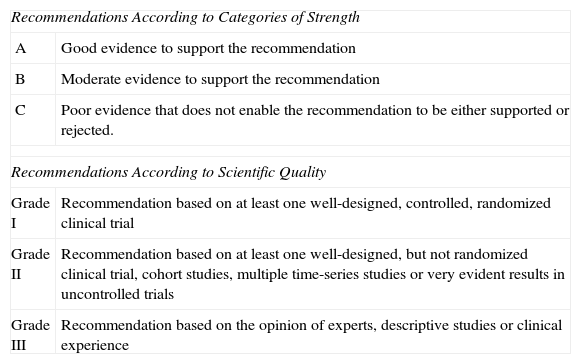

MethodologyThis document has been drafted by a team of experts designated by various scientific societies. All members of the team specialize in the study and monitoring of patients who are candidates for biological therapies. Based on the information obtained, recommendations have been formulated based on the classification of the American Society of Infectious Diseases,9 as per Table 1.

Recommendations by Strength and Scientific Quality.9

| Recommendations According to Categories of Strength | |

| A | Good evidence to support the recommendation |

| B | Moderate evidence to support the recommendation |

| C | Poor evidence that does not enable the recommendation to be either supported or rejected. |

| Recommendations According to Scientific Quality | |

| Grade I | Recommendation based on at least one well-designed, controlled, randomized clinical trial |

| Grade II | Recommendation based on at least one well-designed, but not randomized clinical trial, cohort studies, multiple time-series studies or very evident results in uncontrolled trials |

| Grade III | Recommendation based on the opinion of experts, descriptive studies or clinical experience |

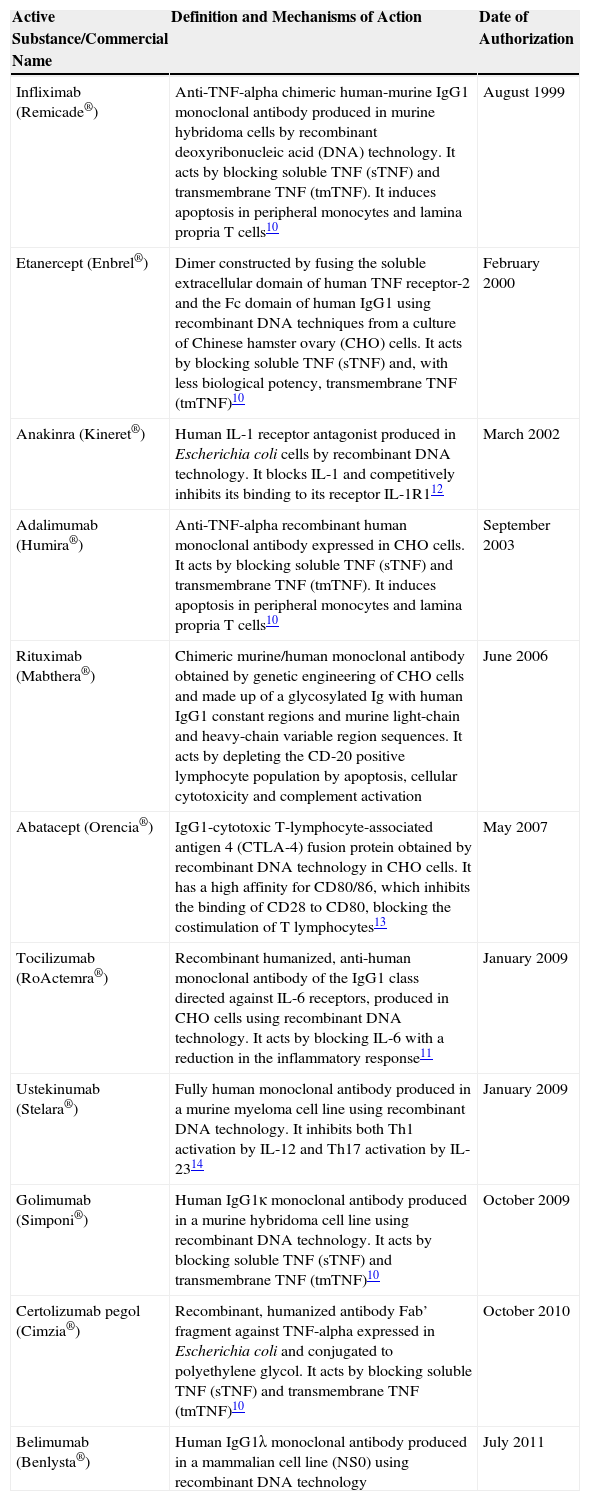

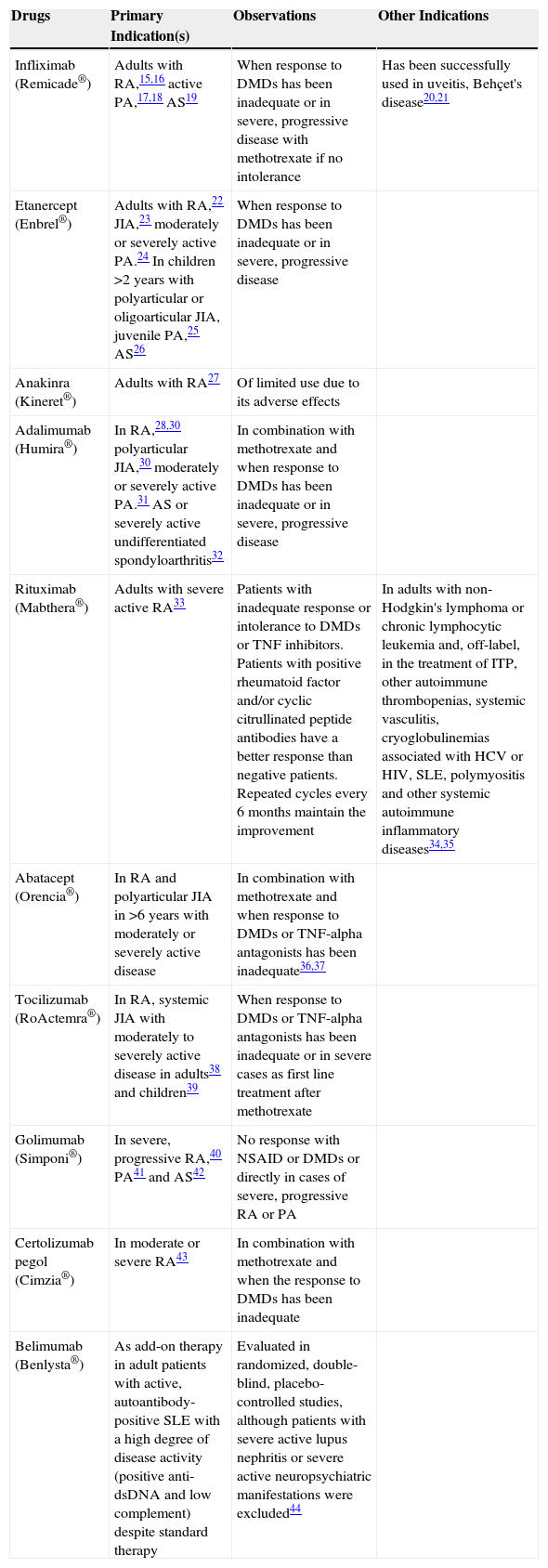

Biological treatments have revolutionized the treatment of systemic autoimmune inflammatory diseases and spondyloarthritis. Before their introduction, only non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), glucocorticoids and so-called disease modifying drugs (DMD) were available which, in general, only slightly modified the natural evolution of RA. Today, disease progression can be halted and complete remission achieved in most patients. Tables 2 and 3 summarize the main drugs used in the treatment of rheumatic diseases and their current indications.10–44

Summary of the Main Biological Therapies Marketed.

| Active Substance/Commercial Name | Definition and Mechanisms of Action | Date of Authorization |

|---|---|---|

| Infliximab (Remicade®) | Anti-TNF-alpha chimeric human-murine IgG1 monoclonal antibody produced in murine hybridoma cells by recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) technology. It acts by blocking soluble TNF (sTNF) and transmembrane TNF (tmTNF). It induces apoptosis in peripheral monocytes and lamina propria T cells10 | August 1999 |

| Etanercept (Enbrel®) | Dimer constructed by fusing the soluble extracellular domain of human TNF receptor-2 and the Fc domain of human IgG1 using recombinant DNA techniques from a culture of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. It acts by blocking soluble TNF (sTNF) and, with less biological potency, transmembrane TNF (tmTNF)10 | February 2000 |

| Anakinra (Kineret®) | Human IL-1 receptor antagonist produced in Escherichia coli cells by recombinant DNA technology. It blocks IL-1 and competitively inhibits its binding to its receptor IL-1R112 | March 2002 |

| Adalimumab (Humira®) | Anti-TNF-alpha recombinant human monoclonal antibody expressed in CHO cells. It acts by blocking soluble TNF (sTNF) and transmembrane TNF (tmTNF). It induces apoptosis in peripheral monocytes and lamina propria T cells10 | September 2003 |

| Rituximab (Mabthera®) | Chimeric murine/human monoclonal antibody obtained by genetic engineering of CHO cells and made up of a glycosylated Ig with human IgG1 constant regions and murine light-chain and heavy-chain variable region sequences. It acts by depleting the CD-20 positive lymphocyte population by apoptosis, cellular cytotoxicity and complement activation | June 2006 |

| Abatacept (Orencia®) | IgG1-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) fusion protein obtained by recombinant DNA technology in CHO cells. It has a high affinity for CD80/86, which inhibits the binding of CD28 to CD80, blocking the costimulation of T lymphocytes13 | May 2007 |

| Tocilizumab (RoActemra®) | Recombinant humanized, anti-human monoclonal antibody of the IgG1 class directed against IL-6 receptors, produced in CHO cells using recombinant DNA technology. It acts by blocking IL-6 with a reduction in the inflammatory response11 | January 2009 |

| Ustekinumab (Stelara®) | Fully human monoclonal antibody produced in a murine myeloma cell line using recombinant DNA technology. It inhibits both Th1 activation by IL-12 and Th17 activation by IL-2314 | January 2009 |

| Golimumab (Simponi®) | Human IgG1κ monoclonal antibody produced in a murine hybridoma cell line using recombinant DNA technology. It acts by blocking soluble TNF (sTNF) and transmembrane TNF (tmTNF)10 | October 2009 |

| Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia®) | Recombinant, humanized antibody Fab’ fragment against TNF-alpha expressed in Escherichia coli and conjugated to polyethylene glycol. It acts by blocking soluble TNF (sTNF) and transmembrane TNF (tmTNF)10 | October 2010 |

| Belimumab (Benlysta®) | Human IgG1λ monoclonal antibody produced in a mammalian cell line (NS0) using recombinant DNA technology | July 2011 |

Summary of Biological Therapies in Rheumatic Diseases.

| Drugs | Primary Indication(s) | Observations | Other Indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infliximab (Remicade®) | Adults with RA,15,16 active PA,17,18 AS19 | When response to DMDs has been inadequate or in severe, progressive disease with methotrexate if no intolerance | Has been successfully used in uveitis, Behçet's disease20,21 |

| Etanercept (Enbrel®) | Adults with RA,22 JIA,23 moderately or severely active PA.24 In children >2 years with polyarticular or oligoarticular JIA, juvenile PA,25 AS26 | When response to DMDs has been inadequate or in severe, progressive disease | |

| Anakinra (Kineret®) | Adults with RA27 | Of limited use due to its adverse effects | |

| Adalimumab (Humira®) | In RA,28,30 polyarticular JIA,30 moderately or severely active PA.31 AS or severely active undifferentiated spondyloarthritis32 | In combination with methotrexate and when response to DMDs has been inadequate or in severe, progressive disease | |

| Rituximab (Mabthera®) | Adults with severe active RA33 | Patients with inadequate response or intolerance to DMDs or TNF inhibitors. Patients with positive rheumatoid factor and/or cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies have a better response than negative patients. Repeated cycles every 6 months maintain the improvement | In adults with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia and, off-label, in the treatment of ITP, other autoimmune thrombopenias, systemic vasculitis, cryoglobulinemias associated with HCV or HIV, SLE, polymyositis and other systemic autoimmune inflammatory diseases34,35 |

| Abatacept (Orencia®) | In RA and polyarticular JIA in >6 years with moderately or severely active disease | In combination with methotrexate and when response to DMDs or TNF-alpha antagonists has been inadequate36,37 | |

| Tocilizumab (RoActemra®) | In RA, systemic JIA with moderately to severely active disease in adults38 and children39 | When response to DMDs or TNF-alpha antagonists has been inadequate or in severe cases as first line treatment after methotrexate | |

| Golimumab (Simponi®) | In severe, progressive RA,40 PA41 and AS42 | No response with NSAID or DMDs or directly in cases of severe, progressive RA or PA | |

| Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia®) | In moderate or severe RA43 | In combination with methotrexate and when the response to DMDs has been inadequate | |

| Belimumab (Benlysta®) | As add-on therapy in adult patients with active, autoantibody-positive SLE with a high degree of disease activity (positive anti-dsDNA and low complement) despite standard therapy | Evaluated in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, although patients with severe active lupus nephritis or severe active neuropsychiatric manifestations were excluded44 |

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; DMDs, disease-modifying drugs; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; PA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes 2 diseases, UC and CD, which are characterized by their chronic nature and alternation of outbreaks between periods of remission that vary in length.

The therapeutic goal includes rapid control of inflammatory activity during flare-ups, in order to improve symptoms and prevent complications that lead to structural damage in the digestive tract, with permanent incapacitating consequences. Once remission has been achieved, the aim of maintenance treatment is for the disease to remain inactive, and to prevent the onset of new outbreaks.

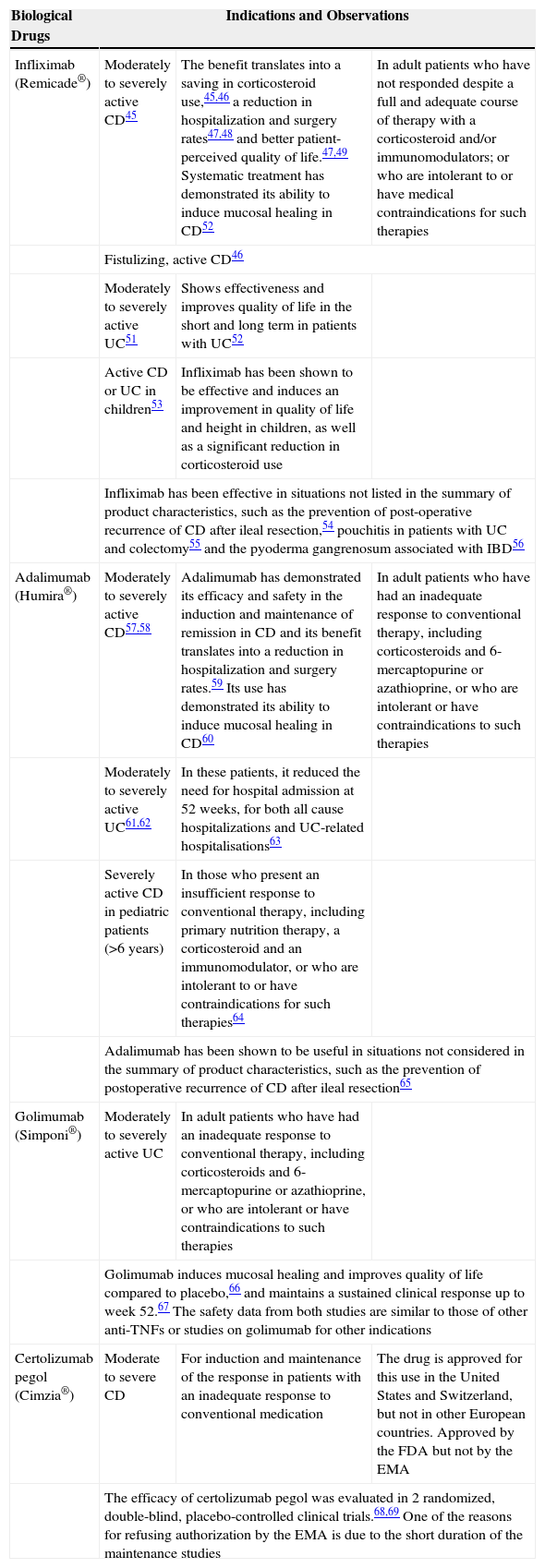

The main biological treatments for IBD and their indications are summarized in Table 4.45–69

Summary of Biological Therapies in Intestinal Diseases.

| Biological Drugs | Indications and Observations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Infliximab (Remicade®) | Moderately to severely active CD45 | The benefit translates into a saving in corticosteroid use,45,46 a reduction in hospitalization and surgery rates47,48 and better patient-perceived quality of life.47,49 Systematic treatment has demonstrated its ability to induce mucosal healing in CD52 | In adult patients who have not responded despite a full and adequate course of therapy with a corticosteroid and/or immunomodulators; or who are intolerant to or have medical contraindications for such therapies |

| Fistulizing, active CD46 | |||

| Moderately to severely active UC51 | Shows effectiveness and improves quality of life in the short and long term in patients with UC52 | ||

| Active CD or UC in children53 | Infliximab has been shown to be effective and induces an improvement in quality of life and height in children, as well as a significant reduction in corticosteroid use | ||

| Infliximab has been effective in situations not listed in the summary of product characteristics, such as the prevention of post-operative recurrence of CD after ileal resection,54 pouchitis in patients with UC and colectomy55 and the pyoderma gangrenosum associated with IBD56 | |||

| Adalimumab (Humira®) | Moderately to severely active CD57,58 | Adalimumab has demonstrated its efficacy and safety in the induction and maintenance of remission in CD and its benefit translates into a reduction in hospitalization and surgery rates.59 Its use has demonstrated its ability to induce mucosal healing in CD60 | In adult patients who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy, including corticosteroids and 6-mercaptopurine or azathioprine, or who are intolerant or have contraindications to such therapies |

| Moderately to severely active UC61,62 | In these patients, it reduced the need for hospital admission at 52 weeks, for both all cause hospitalizations and UC-related hospitalisations63 | ||

| Severely active CD in pediatric patients (>6 years) | In those who present an insufficient response to conventional therapy, including primary nutrition therapy, a corticosteroid and an immunomodulator, or who are intolerant to or have contraindications for such therapies64 | ||

| Adalimumab has been shown to be useful in situations not considered in the summary of product characteristics, such as the prevention of postoperative recurrence of CD after ileal resection65 | |||

| Golimumab (Simponi®) | Moderately to severely active UC | In adult patients who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy, including corticosteroids and 6-mercaptopurine or azathioprine, or who are intolerant or have contraindications to such therapies | |

| Golimumab induces mucosal healing and improves quality of life compared to placebo,66 and maintains a sustained clinical response up to week 52.67 The safety data from both studies are similar to those of other anti-TNFs or studies on golimumab for other indications | |||

| Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia®) | Moderate to severe CD | For induction and maintenance of the response in patients with an inadequate response to conventional medication | The drug is approved for this use in the United States and Switzerland, but not in other European countries. Approved by the FDA but not by the EMA |

| The efficacy of certolizumab pegol was evaluated in 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials.68,69 One of the reasons for refusing authorization by the EMA is due to the short duration of the maintenance studies | |||

CD, Crohn's disease; EMA, European Medicines Agency; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

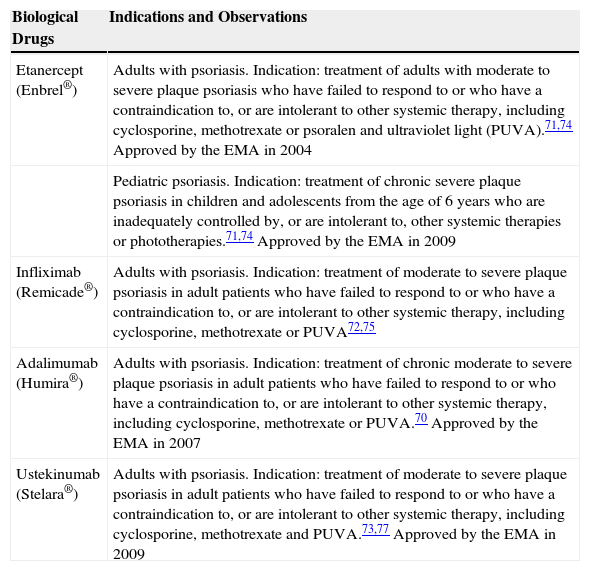

Today, the biological drugs used in the treatment of psoriasis (the only approved dermatological indication) are as follows: etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab and ustekinumab. The summary of product characteristics of these 4 drugs state that they have been approved for the “treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who failed to respond to, or who have a contraindication to, or who are intolerant to other systemic therapy including cyclosporine, methotrexate or PUVA”.70–73Table 5 summarizes the indications for each biological drug in psoriasis.70–77

Summary of Biological Therapies in Dermatological Diseases.

| Biological Drugs | Indications and Observations |

|---|---|

| Etanercept (Enbrel®) | Adults with psoriasis. Indication: treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who have failed to respond to or who have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to other systemic therapy, including cyclosporine, methotrexate or psoralen and ultraviolet light (PUVA).71,74 Approved by the EMA in 2004 |

| Pediatric psoriasis. Indication: treatment of chronic severe plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents from the age of 6 years who are inadequately controlled by, or are intolerant to, other systemic therapies or phototherapies.71,74 Approved by the EMA in 2009 | |

| Infliximab (Remicade®) | Adults with psoriasis. Indication: treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who have failed to respond to or who have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to other systemic therapy, including cyclosporine, methotrexate or PUVA72,75 |

| Adalimumab (Humira®) | Adults with psoriasis. Indication: treatment of chronic moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who have failed to respond to or who have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to other systemic therapy, including cyclosporine, methotrexate or PUVA.70 Approved by the EMA in 2007 |

| Ustekinumab (Stelara®) | Adults with psoriasis. Indication: treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who have failed to respond to or who have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to other systemic therapy, including cyclosporine, methotrexate and PUVA.73,77 Approved by the EMA in 2009 |

EMA, European Medicines Agency.

Tuberculosis infection is caused by the inhalation of viable bacilli which, in general, persist in an inactive state known as LTBI. These, however, can sometimes progress rapidly to active tuberculosis. Persons with LTBI remain asymptomatic and are not contagious. In most individuals, the initial infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is contained by the host's defenses, and remains latent. Nevertheless, this latent infection can become active disease at any time.

The risk of tuberculosis reactivation with anti-TNF depends on 2 variables: the immunomodulatory effect of treatment, and the prevalence of underlying tuberculosis infection in a particular population.

Treatment of the latent infection does not provide total protection,78 and the existence of a standard period for reactivation has not been determined, as this varies according to the drug used.79 The British Society for Rheumatology biologics register (BSRBR) detected an incidence of TB of 39 cases per 100000 patients/year with etanercept, 103 cases per 100000 with infliximab, and 171 cases per 100000 with adalimumab.

Diagnostic Techniques for Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Usefulness in Immunosuppressed PatientsThe investigation of possible tuberculosis infection among patients who are candidates for biological treatments should commence with evaluation of the potential risk of exposure to M. tuberculosis. The groups at highest risk are:

- a.

Persons who have had recent contact with tuberculosis patients.

- b.

Persons who are born or who reside in countries with a high prevalence of TB, or who travel frequently to these areas for business, family or humanitarian reasons.

- c.

Residents and workers in closed institutions, such as jails, homeless shelters or social-healthcare centers of all types.

- d.

Persons with a positive reaction to the tuberculin skin test (TST) who have not received specific treatment.

- e.

Persons who abuse alcohol or other toxic substances, while remembering also that TB is more common in smokers than in non-smokers.

- f.

Healthcare workers, particularly those who treat patients with active TB.

- g.

Patients with radiological lesions suggestive of old TB, especially if they have never received treatment, as is the case of persons with a positive tuberculin test.

- h.

Typically, also individuals at the extremes of life, those with immunosuppressive diseases and other comorbidities that have been related with a higher risk of TB. These conditions include not only HIV infection, autoimmune diseases and post-transplantation, but also lung diseases (silicosis), chronic renal failure, gastrectomy, diabetes and some tumors, such as head and neck cancers.

In the absence of a reference test for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection, current management of patients with autoimmune diseases who are candidates for treatment with anti-TNF drugs includes taking the patient's medical history (aimed at discovering any history of TB or latent infection, previously treated or untreated), looking for evidence of previous TB on the chest X-ray, and performing a TST.

The TST consists of measuring the delayed hypersensitivity reaction that occurs on the skin after intradermal inoculation of the purified protein derivative (PPD), a mixture of more than 200 M. tuberculosis proteins. Given that the antigens contained in the PPD are also found in other mycobacteria, vaccination with BCG can be a cause of false positives in the TST. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the TST is affected in patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment, in which a high percentage of false negatives has been observed.80,81 In this respect, some studies in patients with RA have shown a rate of false positive TSTs as high as 40%.82 A repeat TST is sometimes recommended to increase sensitivity due to the booster effect on false negatives, but this also reduces its specificity by increasing the number of false positives due to the BCG vaccination and exposure to non-tuberculous mycobacteria.83

Diagnostic Techniques Based on Interferon-Gamma ReleaseGenome sequencing of M. tuberculosis has improved identification of the genes involved in its pathogenesis and revealed the presence of genetically different regions. M. tuberculosis proteins (ESAT-6 and CFP-10) are encoded in the region known as RD1, and behave as specific antigens. In persons infected by M. tuberculosis, these induce a type Th-1 immune response with production of interferon gamma (IFN-γ). This region, absent in all strains of M. bovis-BCG and in almost all non-tuberculous mycobacteria (except for M. kansasii, M. marinum and M. szulgai), is present in all known virulent strains of M. tuberculosis.

Interferon-gamma release assays (IGRA) are based on the detection, in the peripheral blood of infected individuals, of IFN-γ released by sensitized T cells in response to in vitro stimulation with M. tuberculosis-specific antigens.

There are two commercial kits available:

- a.

QuantiFERON®-TB-Gold (Cellestis Ltd., Carnegie, Australia),84 which determines the total IFN-γ production in individuals infected by M. tuberculosis using an ELISA technique. A value greater than or equal to 0.35IU/ml is considered positive.

- b.

T-SPOT.TB® (Oxford Immunotec Ltd., United Kingdom), developed by A. Lalvani in the late nineties.85 This is a more laborious procedure that requires monocytes to be separated before incubating them with the ESAT-6 and CFP-10 antigens. It is read using the ELISPOT technique, in which each spot represents an IFN-γ-secreting T cell. The result is considered positive when there are ≥6 spots.

Both techniques include positive and negative controls that can detect false results due to anergy or immunological problems (reported as ‘indeterminate’ results).86 When results are inconclusive (more common in IMID), most guidelines recommend repeating the test, which in many cases confirms the negative result.87,88

IGRA techniques have several advantages over the TST:

- a.

They eliminate subjectivity in the interpretation of results.

- b.

The test can be repeated if necessary.

- c.

There is no need for the patient to return 48–72h later for the results to be read.

- d.

They are easy to standardize and apply in the laboratory.

- e.

They enable anergic patients to be detected.

- f.

They respect the patient's privacy.

Disadvantages include the cost, which is higher than that of the TST.

Interpretation of Results in Patients Who Are Candidates for Biological TreatmentsIGRA techniques are used as routine tests for the diagnosis of LTBI in the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, and in some western European countries (United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Switzerland). Some countries use them instead of the TST, while others combine both tests. In Spain, it is recommended that the TST be complemented with an IGRA technique in persons who are candidates for treatment if they have been vaccinated with BCG (to rule out a false positive tuberculin test), and in those with a negative skin test and suspected immunosuppression (to rule out a false negative tuberculin test).89,90

Despite numerous studies published in recent years, data on the diagnostic yield of these tests in patients with IMID are limited and controversial.80,89,91–94 According to published studies: (a) concordance between the TST and IGRA tests is weaker in patients with systemic inflammatory diseases than in healthy subjects, due to the lower prevalence of positive tuberculin tests among the former82,95–100; (b) the magnitude of the tuberculin response is significantly lower in patients with IMID than in healthy controls82; (c) in vaccinated individuals, a discrepancy has been observed between a positive TST and a negative result in an IGRA test; and (d) in patients receiving corticosteroid treatment, a discrepancy is often observed between a negative TST and a positive IGRA test.96

Due to the vulnerability of these patients to TB while receiving anti-TNF treatment, it would seem prudent to perform both tests (IGRA and TST) in parallel in order to maximize the diagnostic sensitivity of screening, at least until evidence of the usefulness of IGRA techniques in this population has been established.88 It is important to mention that when both tests are performed sequentially, the IGRA tests should be performed first, to prevent the booster effect caused by the TST.101,102 It is not known how long this effect persists, or whether it depends on the amount of PPD administered or its characteristics.

The results of IGRA tests in patients on anti-TNF treatment remain difficult to interpret. Data from recent studies103–105 show conversions and reversions in both tests, which are related with reproducibility problems and changes in patients’ immune status. This variability means that it is not advisable to repeat the tests for patient's follow-up during treatment.

Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Treatment GuidelinesThe identification and treatment of LTBI reduces the likelihood of reactivation in these patients, thereby protecting their health and that of other people in their environment by reducing the number of possible sources of infection.106,107 Treatment of latent infection should only be initiated once active TB has been excluded.

LTBI treatment regimens include INH for 9 months, rifampicin (RIF) alone for 4 months, or INH with RIF for 3 months.108

Isoniazid. The usual dose is 5mg/kg/day, with a maximum of 300mg daily in adults. The only study to compare the efficacy of different durations of INH treatment showed an efficacy of 65% in the 6 month regimen, while in the 12 month regimen the efficacy was 75% (not significantly different from the former).109 Extrapolating the data from randomized trials shows that the optimal duration of INH treatment for LTBI is 9 months.109,110 The major side effect of INH is hepatitis, with an incidence of 1 case in every 1000 persons.111

Rifampicin. The usual dose is 10mg/kg/day, with a maximum of 600mg daily. The efficacy of RIF in reducing the incidence of active TB is thought to be similar to that of INH.112,113 Although little data is available, RIF appears to be well tolerated, with a low rate of hepatotoxicity.112

Isoniazid and Rifampicin. There is little data on the use of the combination of INH and RIF in HIV-negative patients, but some studies have shown that it is an effective regimen, with good adherence and well tolerated.114 A meta-analysis of small studies conducted in the non-HIV population concluded that it is equally effective and no more toxic.115

Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Patients Who Are Candidates for Biological TherapiesThe United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends treatment of LTBI in patients scheduled to start treatment with a TNF inhibitor and who have a positive TST (≥5mm induration) or a positive IGRA test, regardless of whether they have been vaccinated with BCG (as its effect on the TST is greatly attenuated over time).116–118 It is also recommended in the case of patients with negative TST or IGRA in whom there is evidence of untreated tuberculosis on the chest X-ray, or epidemiological evidence of previous exposure to TB (for example, after having been in close contact with a person infected with TB or having resided in a country with a high incidence of TB).

In general, candidates for anti-TNF who are indicated for LTBI treatment receive standard treatment, i.e. INH for 9 months. The recommended duration of LTBI therapy before starting a TNF inhibitor is not well established, but most authors propose that, whenever possible, patients receive LTBI therapy for at least 1 month before starting the anti-TNF regimen.8,119

Treatment of the latent infection with INH will not protect the patient against reactivation of the infection by INH-resistant strains.120 RIF is indicated in the case of patients who are intolerant to INH, or whose index cases present strains resistant to INH but sensitive to RIF.

Recommendations of the Consensus DocumentThe recommendations summarized here are based on evidence published up to 2013, on various national guidelines, and on the opinions of experts specializing in the treatment of patients with IMID who may be candidates for receiving biological treatment.

These recommendations are:

- 1.

All patients who are candidates for biological treatment should be studied to detect a possible LTBI, given that they constitute one of the groups at highest risk of developing tuberculosis (AII).

- 2.

The risk of these patients for developing the disease is related with the anti-TNF drug used. Infliximab and adalimumab are associated with the highest risk (AIII).

- 3.

Methods for diagnosing LTBI are based on:

- -

Review of the patient's medical record to show a history of TB or contact with patients with active TB.

- -

Evidence of possible old tuberculous lesions on the chest X-ray. In case of doubt, the study should be completed with a chest computed tomography (CT) scan, which is more accurate than conventional radiology in detecting early radiological signs of active TB or old lesions.

- -

Simultaneous performance of IGRA tests and a TST. A positive result in any of these tests is considered indicative of LTBI (AIII).

- -

- 4.

False negative results in the TST and IGRA tests are more common in patients diagnosed with IMID (AIII).

- 5.

Repeating the TST (booster effect) has not been shown to improve the sensitivity of the test in IMIDs, and reduces its specificity; therefore, it is not currently recommended, as IGRA techniques are available (CIII).

- 6.

Blood for IGRA tests should be extracted before the TST, due to the booster effect identified on IGRA tests (AIII).

- 7.

The specificity and sensitivity of both IGRA techniques for the diagnosis of LTBI is similar in patients with IMID, although the sensitivity of the T-SPOT.TB is somewhat greater in patients treated with corticosteroids. Its use should therefore be assessed in these patients (BIII).

- 8.

Indeterminate results in IGRA tests should always be confirmed with a second test, which is usually negative in most cases (AIII).

- 9.

A negative result in the TST and IGRA tests does not rule out the presence of an LTBI (AIII).

- 10.

Preventive treatment is recommended in all candidates for biological therapies who present positive results in any diagnostic test for LTBI, once active TB has been excluded (AII).

- 11.

The recommended treatment regimen is INH for 9 months. In exceptional cases only, treatment with INH+RIF for 3 months may be indicated (AIII).

- 12.

Treatment should be monitored each month. In the event of INH-induced hepatotoxicity, an alternative regimen with RIF for 4 months is recommended (AIII).

- 13.

Treatment of the LTBI for 4 weeks is considered safe (by most experts) for initiating anti-TNF treatment (AIII).

- 14.

According to current data, study and screening of the LTBI after the start of and during anti-TNF treatment are not indicated as a strategy for diagnosing initial false negatives. The screening study should only be repeated if there are changes in the clinical symptoms or after possible exposure to M. tuberculosis on travel to highly endemic areas (AIII).

- 15.

If the patient is diagnosed with active tuberculosis, anti-TNF treatment should be suspended and not re-started until the entire anti-tuberculosis treatment cycle has been completed. There is no evidence that the duration of treatment of the disease due to TB should be modified in this context (AIII).

- 16.

The risk of relapse in patients who have correctly completed tuberculosis treatment does not seem to be higher after starting anti-TNF treatment (AIII).

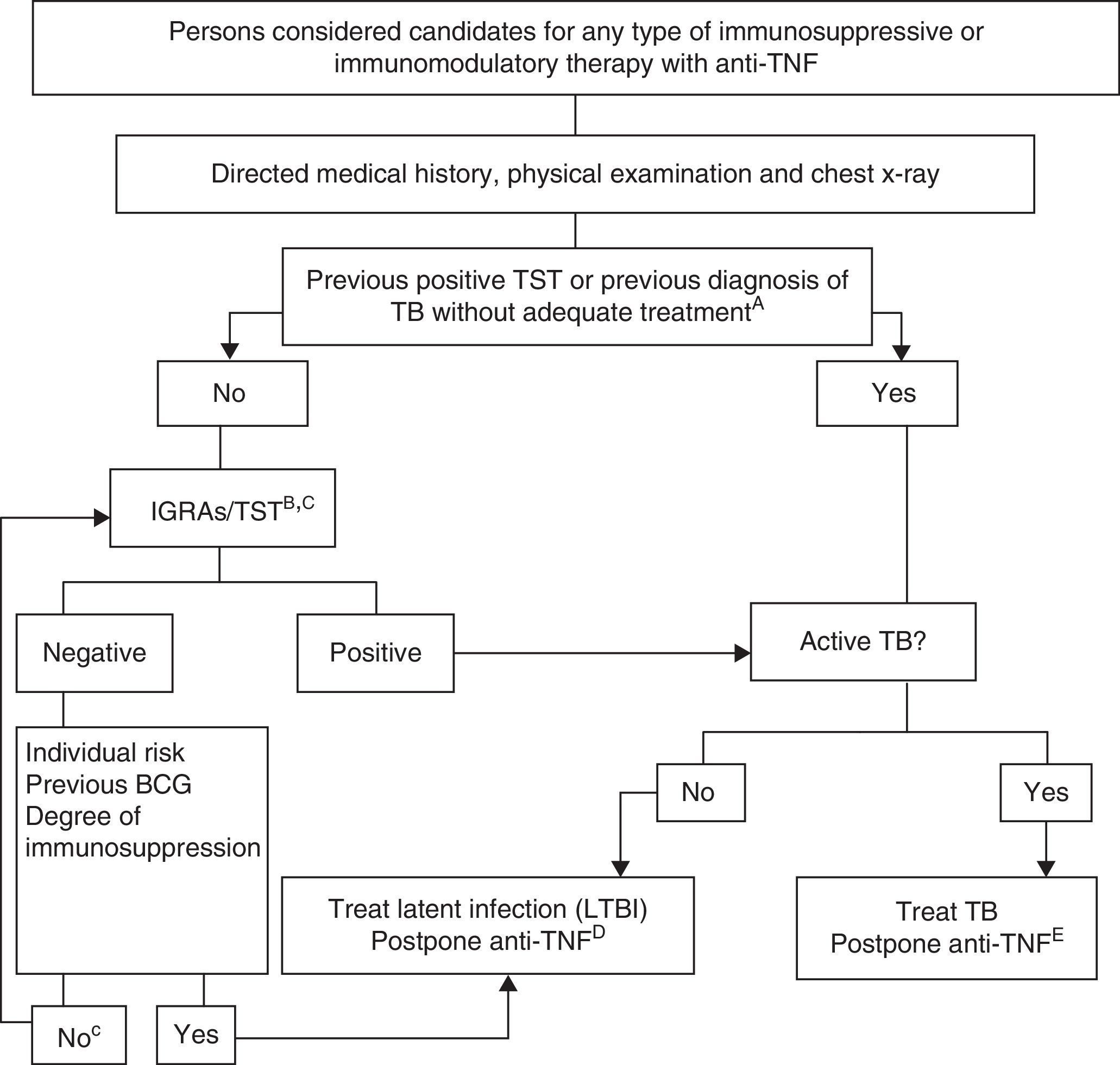

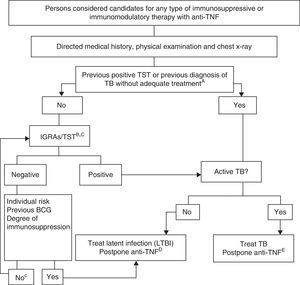

Fig. 1 shows the proposed algorithm for evaluating tuberculosis in patients who are candidates for biological treatments,121 in which the following determinants were used:

- A.

Adequate treatment of the TB is defined as ≥6 months of therapy with first line drugs, and includes ≥2 months with the combination RIF+INH+pyrazinamide+ethambutol. Latent infection can be adequately treated with 9 months of INH, 3 months of INH+RIF or 4 months of RIF alone.

- B.

The risk of latent infection is derived from considering factors such as known exposure to a contagious case, age, country of origin, and work and social history, including travel to endemic countries and repeated exposure to risk groups (closed institutions, homeless persons, drug users).

- C.

In persons who have been LTBI carriers for many years, the TST can be negative and become positive in a second TST (booster phenomenon). A second test is not recommended due to the availability of IGRA techniques. The study should only be repeated according to recommendation no. 14.

- D.

There are no conclusive data that allow a safe period to be established between the start of treatment of the latent infection and the start of anti-TNF treatment. Most experts consider that a delay of 4 weeks is a safe standard practice.

- E.

Treatment of the active TB must be completed before initiating the biological treatment.

Esteban Daudén Tello declares that he is a member of an advisory board, a consultant, has received grants and research grants, has participated in clinical trials, and has received honoraria as a speaker from the following pharmaceutical companies: AbbVie (Abbott), Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, MSD, Pfizer, Novartis, Celgene and Lilly.

Carlos Taxonara Samso declares that he has been a consultant and speaker for MSD and AbbVie.

Francisco Javier López Longo declares occasional contracts as a speaker with AbbVie, Actelion, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, GSK, MSD, Pfizer, Roche Farma and UCB, and has received research funding from AbbVie and GSK.

The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Mir Viladrich I, Daudén Tello E, Solano-López G, López Longo FJ, Taxonera Samso C, Sánchez Martínez P, et al. Documento de consenso sobre la prevención y el tratamiento de la tuberculosis en pacientes candidatos a tratamiento biológico. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:36–45.

Consensus Document from the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), Spanish Society of Digestive Diseases (SEPD), Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) and Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC).