The introduction of artificial stone (AS) in industries that handled marble has caused a significant increase in silicosis cases.1,2 In 2010, the first cases of silicosis due to AS were published in Spain3 and later they were reported in other countries.1,2 To date, information about the evolution of the disease and its laboral consequences is lacking.

This is an observational study in which AS silicosis patients were evaluated between January 2006 and June 2021. Once the diagnosis of the first patient (index case) was completed, the other workers who handled AS from the same company were also evaluated. The diagnosis was based on occupational exposure to AS, radiological findings, and the exclusion of other entities. The chest X-ray was assessed according to the International Labour Office criteria4 and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) as described by Kusaka et al.5 When the diagnosis was not considered certain, a compatible histological sample was required.

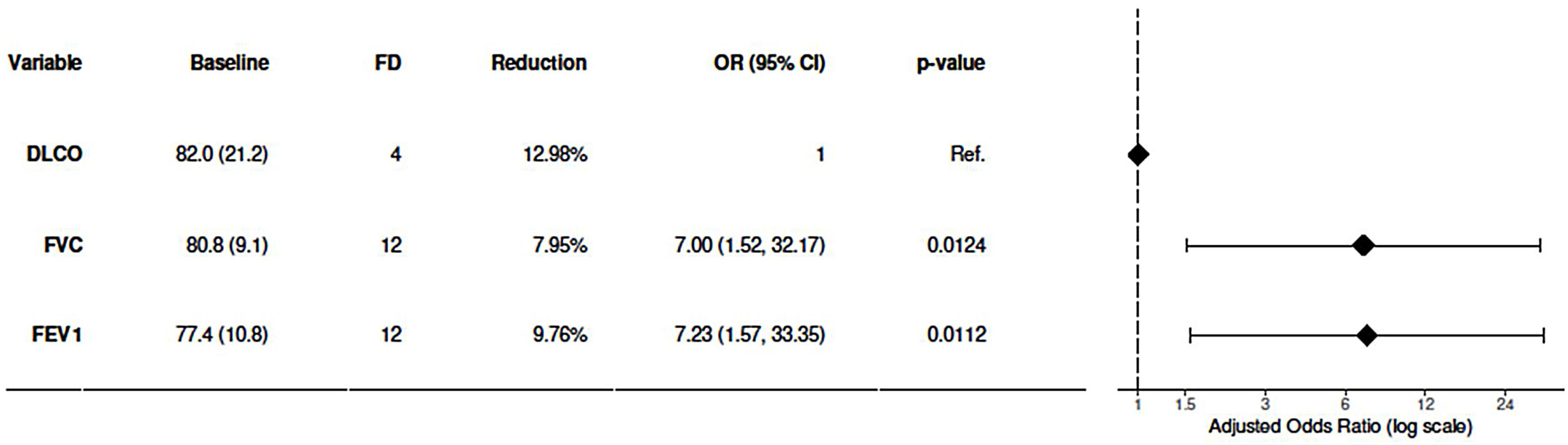

The aim of the study was to analyze the clinical, functional, radiological and occupational evolution of a series of AS silicotic patients referred from an occupational health company. A clinical and occupational evaluation, lung function test, chest X-ray and high-resolution computed tomography were performed at diagnosis and at follow-up, at least annually. Silicosis progression was considered if there were radiological changes4,5 with or without worsening of dyspnoea6 or a functional decrease (FVC ≥5%/year, FEV1 ≥5%/year and DLCO ≥7.5%/year).7–10 The radiological images were analyzed independently by a pulmonologist and a radiologist. If the two evaluators did not agree, the decision was made by consensus. SPSS (v.2.0) and R 4.12 were used for statistical analysis. The patient's informed consent and the approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Dr. Josep Trueta University Hospital in Girona (CEIM code: 2021/133) were obtained.

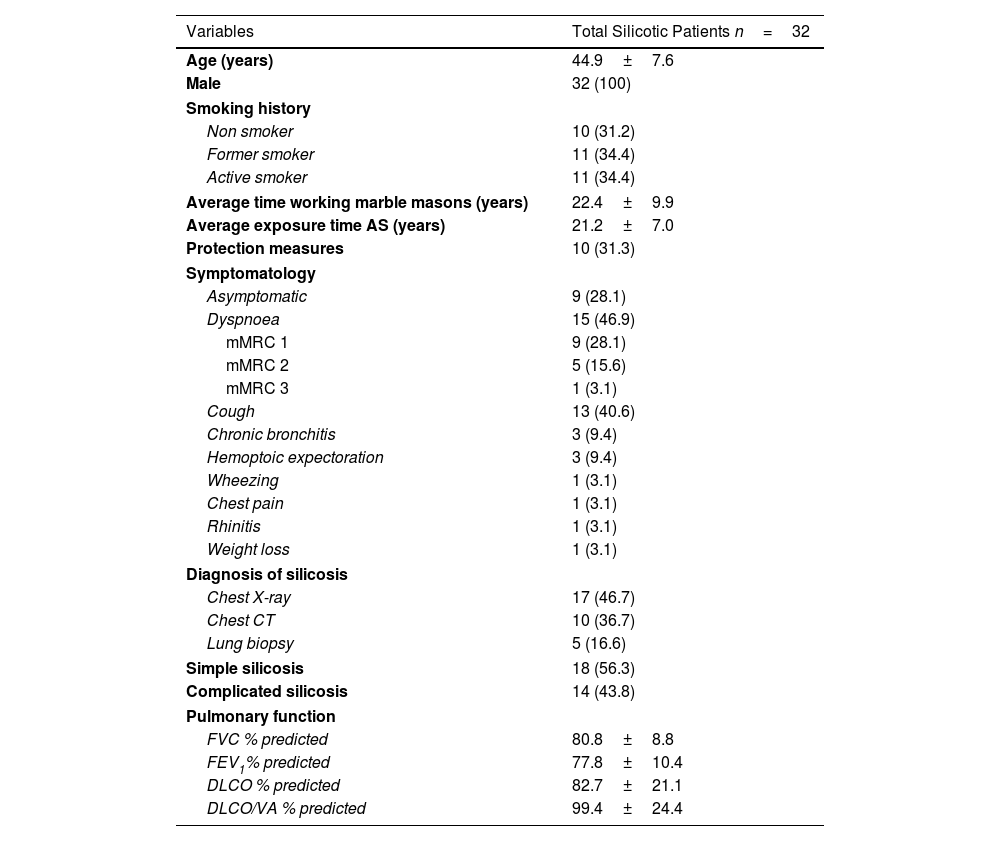

Thirty-two patients were included, all men with a mean age of 44.9±7.6 (Table 1). The mean time of exposure to AS was 21.2±7.0 years. The most frequent clinical presentation was dyspnoea in 15 of the patients (46.9%). Nine patients (28.1%) had no symptoms. A non-obstructive functional disorder was found in 13 of the patients (40.6%) and an obstructive functional disorder in 9 of them (28.1%). In 10 of the patients (31.2%), the respiratory function was normal. The diagnosis was confirmed by an imaging technique in 84.4% of the patients and by an histological study in the remaining 16.6%. Eighteen of the patients (56.3%) met the criteria for simple silicosis and 14 (43.8%) for complicated silicosis.

Demographic Variables and Clinical Characteristics of Silicotic Patients.

| Variables | Total Silicotic Patients n=32 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.9±7.6 |

| Male | 32 (100) |

| Smoking history | |

| Non smoker | 10 (31.2) |

| Former smoker | 11 (34.4) |

| Active smoker | 11 (34.4) |

| Average time working marble masons (years) | 22.4±9.9 |

| Average exposure time AS (years) | 21.2±7.0 |

| Protection measures | 10 (31.3) |

| Symptomatology | |

| Asymptomatic | 9 (28.1) |

| Dyspnoea | 15 (46.9) |

| mMRC 1 | 9 (28.1) |

| mMRC 2 | 5 (15.6) |

| mMRC 3 | 1 (3.1) |

| Cough | 13 (40.6) |

| Chronic bronchitis | 3 (9.4) |

| Hemoptoic expectoration | 3 (9.4) |

| Wheezing | 1 (3.1) |

| Chest pain | 1 (3.1) |

| Rhinitis | 1 (3.1) |

| Weight loss | 1 (3.1) |

| Diagnosis of silicosis | |

| Chest X-ray | 17 (46.7) |

| Chest CT | 10 (36.7) |

| Lung biopsy | 5 (16.6) |

| Simple silicosis | 18 (56.3) |

| Complicated silicosis | 14 (43.8) |

| Pulmonary function | |

| FVC % predicted | 80.8±8.8 |

| FEV1% predicted | 77.8±10.4 |

| DLCO % predicted | 82.7±21.1 |

| DLCO/VA % predicted | 99.4±24.4 |

mMRC: Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnoea Scale; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in first second; DLCO: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; VA: alveolar volume.

Evolution was followed for 39.6±34.5 months. Three patients (9.3%) progressed from simple to complicated and 1 patient presented an accelerated course. At the end of follow-up, 17 (53.1%) patients were classified as complicated silicosis. Additionally, 10 (31.3%) patients worsened clinically and 14 (43.8%) functionally. There was deterioration of FVC in 12 patients (37.5%), of FEV1 in 12 of the patients (37.5%), and of DLCO in 4 patients (12.5%) (Fig. 1). The annual reduction of these parameters in those patients was 7.95%, 9.76% and 12.98%, respectively. The probability of verifying functional decline was 7 times higher when assessed by FVC or FEV1 than when it was determined by DLCO (Fig. 1). In addition, 2 patients (6.3%) were diagnosed with tuberculosis and 4 (12.5%), all smokers, developed an obstructive functional disorder. Thus, a total of 10 (31.2%) patients were classified as having chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at the end of follow-up. Finally, 2 patients (6.3%) underwent transplantation due to silicosis progression.

The 32 patients studied worked in 14 different companies. We obtained reliable information from 9 of the 14 companies included. Twenty-seven out of 61 workers who handled AS were diagnosed with silicosis (44.3% prevalence). After detecting an index case, 24 (88.9%) silicotic patients came together as clusters in the 9 companies studied.

Permanent disability that precluded any employment was provided in 2 (6.3%) of all patients. Permanent disability in terms of the job that caused the silicosis as well as other jobs entailing exposure to the same causative agent was provided in other 27 (84%) of patients. The patient's disability was financially compensated. Additionally, 3 patients (9.4%) diagnosed of simple silicosis without functional impairment had not legal criteria to be subsidized in Spain.11 None of the patients worked as an AS worker after diagnosis. Sixteen (50%) patients became unemployed. We were not aware of the working situation of 3 patients. Only 1 (7.7%) of the remaining 13 patients who found another job, it was in the same company.

Our study has some limitations: the size of the sample was limited, the study was performed in a single centre and data was collected retrospectively.

Patients stand out due to their young age and the lack or limited symptoms at the time of diagnosis. These characteristics would explain that despite the advanced disease stage, they were in full employment. It also remarks the deficiency in adopting prevention measures. Although several studies have reported that 6.6% to 15% of patients with AS silicosis present complicated silicosis at diagnosis,12,13 it is very remarkable that 43.8% of our patients were classified with complicated silicosis. These differences could be explained by the fact that the exposure time before diagnosis was 22 years in our study, while in those others studies it was between 7.32 and 1514 years. During evolution, 3 patients progressed from simple to complicated silicosis, which means that more than half of the patients had this advanced form of the disease at the end of follow-up. Our data, together with a high demand for lung transplantation suggest a serious aggressiveness.

As in other studies15,16 a non-obstructive alteration was the most frequent functional pattern found in our patients. However, several studies have also shown that obstruction is a functional alteration often present in chronic silicosis and, as well, in AS silicosis.14 In our study, 18.8% of the patients presented obstruction at the time of diagnosis and in 12.5% of them it was confirmed at follow-up. Although smoking and other lung diseases such as healed tuberculosis need to be considered, silica is also recognized as a cause of COPD.17 A 43.8% of our patients, experienced a significant decrease in lung function. FVC and FEV1 declined roughly the same rate, as it has also been mentioned in other silicosis.18 This is indicative of a predominantly restrictive pattern. Moreover, a functional decline was observed more frequently with ventilatory parameters than DLCO. This fact had already been mentioned in other silicosis19 and has also been recently reported in CAC silicosis.12

Based on the detection of index cases, other workers were found and diagnosed with silicosis. Thus, as previously reported,1 micro-epidemics of silicosis could not be avoided in the companies involved. Although the proper use of screening protocols, surveillance, and awareness of occupational risk in these workers are mandatory,20 it seems clear that other measures are necessary. An adequate evaluation and controlled tests of materials and processes before their introduction in the workplace, should assess the possibility that these changes could pose a risk to the health of workers. Finally, our study found that 50% of the patients became unemployed after the diagnosis of silicosis and only one (7.7%) remained employed in the same company. This fact shows the importance of having suitable legal benefits, given the economic and social consequences that this occupational disease can cause.

Authors’ ContributionsRO: (1) the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

AT, MTC, GS: (1) acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

MCC, OTC, MV: (1) analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

FundingMCC was a recipient of Serra Húnter fellowship and OTC was a recipient of a Miguel Servet grant from the Institute of Health Carlos III (CP17/00114).

This research did not receive any other specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

The authors would like to thank all the study participants and the companies for providing the information and Neus Luque for support in the manuscript format.