Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent worldwide.1 In patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) vitamin D deficiency is much higher – 95% in the Spanish2 and Japanese,3 80% in the Iranian4 and 54% in the Argentinian5 cohorts – than in the general population. Likewise, secondary hyperparathyroidism, a consequence of severe vitamin D deficit, is also highly prevalent in PAH.2,6

Several studies have retrospectively analyzed the prognosis and clinical impact of vitamin D deficiency in PAH. Patients with total 25(OH)vitD plasma below the median in the Spanish cohort (7.2ng/ml) had worse functional class, higher BNP/pro-BNP levels, lower 6-min walking distance (6MWD) and lower tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE).2 Survival in patients with vitamin D levels above the median was markedly increased than in those below the median value (age-adjusted hazard ratio: 5.40 [CI95 2.88–10.12]). In the Argentinian cohort, there was higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in patients with worse functional class and a linear correlation between 6MWD and vitamin D levels.5 In the Japanese cohort, vitamin D levels showed a significant correlation with cardiac output.3 Moreover, low vitamin D levels are associated with a poor therapeutic response to PDE5 inhibitors.7 In addition, vitamin D deficiency was also associated with group 3 pulmonary hypertension. In a recent retrospective study, vitamin D deficiency was present in 35% of controls, 57% of patients with COPD and 86% of patients with COPD plus pulmonary hypertension. Vitamin D was negatively correlated with pulmonary artery systolic blood pressure.8

At present, there is no clear evidence to support that there is a causal link, at least in humans, between vitamin D deficiency and PAH. Moreover, if present, the causal relationship might be in either direction: vitamin D causing/aggravating PAH or PAH inducing vitamin D deficiency. Nonetheless, data from preclinical and small uncontrolled trials suggest that low vitamin D aggravates PAH. In rats with PAH, induced by either hypoxia plus Su54169 or by monocrotaline,10 vitamin D deficiency aggravated the increase in mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP), right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy and other biomarkers of PAH. The combination of Bmpr2 loss of function mutation plus vitamin D free diet in rats induced additive or synergic right atrial enlargement, increased plasma BNP and cardiac calcification, i.e. three well-known risk factors of poor prognosis in PAH.11 Interestingly, in PAH rats with vitamin D deficiency, restoration of vitamin D levels improved the in vitro response to the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil, mimicking the different vitamin D-dependent responsiveness to PDE5 inhibitors in PAH patients.7 In addition, there is a small (n=28) prospective uncontrolled longitudinal trial in Iranian patients with pulmonary hypertension (mostly PAH) and vitamin D deficiency that were given 50,000IU cholecalciferol weekly plus calcicare (200mg magnesium+8mg zinc+400IU vit D) daily for 3 months.4 The serum vitamin D level increased from 14 (SD 9) to 69 (31)ng/ml (p<0.001), the mean 6MWD increased from 260 (SD 124) to 331 (139), p<0.001, and the RV size significantly improved.

From a mechanistic point of view, the active form of vitamin D, calcitriol, activates the vitamin D receptor (VDR), a transcriptional factor that regulates the expression of specific target genes12 relevant in key processes within the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, such as cell proliferation, differentiation and migration, control of vascular tone, immunomodulation and regulation of metabolism among others. Vitamin D has been reported to directly modulate the activity and expression of several targets involved in PAH. Notably, it regulates the TGF-β and BMPR2 pathway by interfering with its intracellular signalling molecule SMAD3. Thus, vitamin D analogues inhibit TGF-β effects in multiple tissues.13 Vitamin D also regulates the BMPR2 ligands BMP4 and BMP6, the calcineurin-NFAT and the mTOR-S6 signalling pathways and modulates thrombospondin-1, survivin, interleukin-17, interleukin-6 and KCNK3 expression.9

There are some relevant questions that remain to be answered: (1) Does vitamin D deficiency trigger the development of PAH in predisposed subjects? (2) Does vitamin D deficiency aggravate symptoms and prognosis in PAH patients? and moreover, the key clinical question for PAH patients is: (3) Does restoration of vitamin D levels lead to clinical improvement and better prognosis in PAH patients?

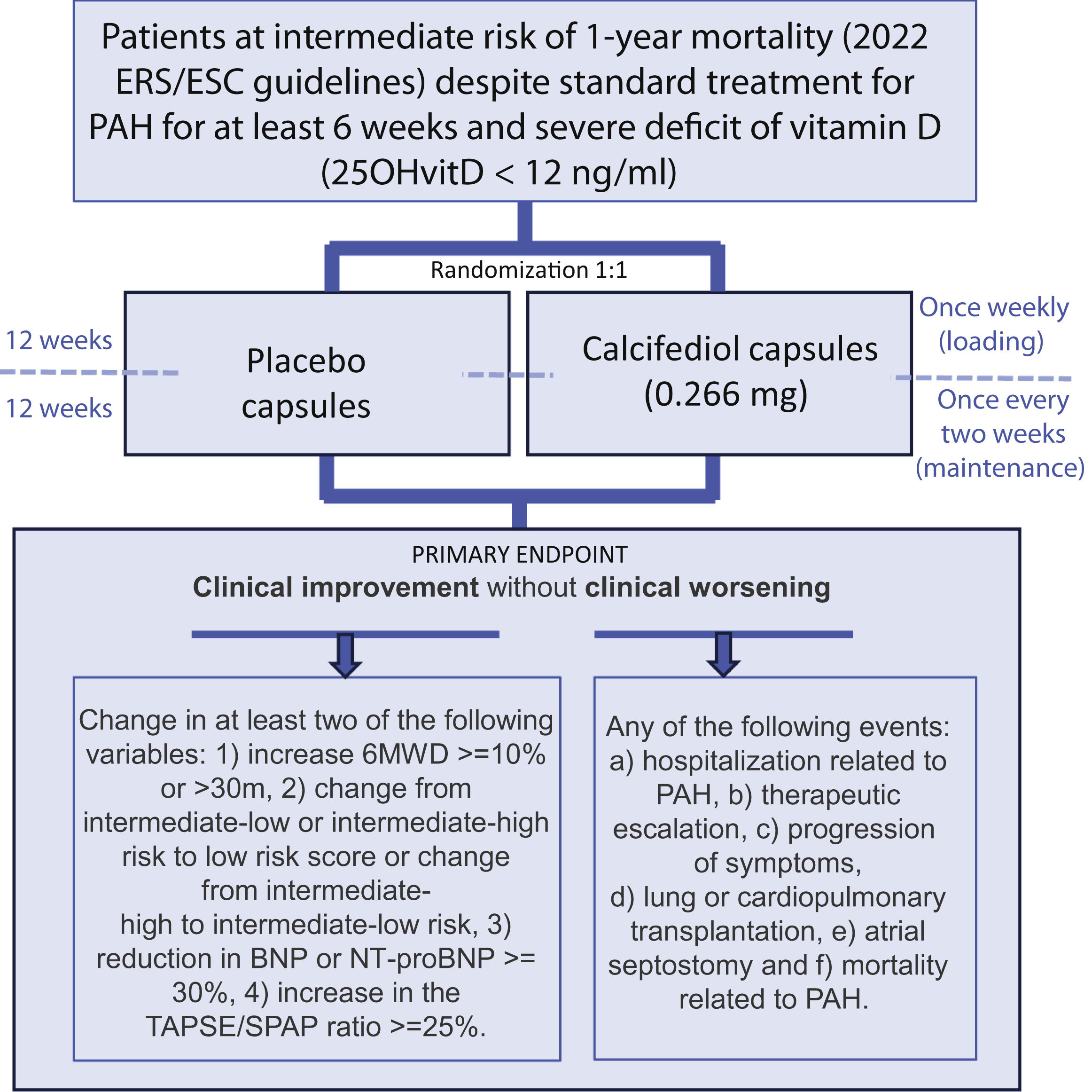

Thus, we hypothesize that in patients with stable PAH and vitamin D deficiency, restoration of vitamin D status improves symptoms and prognosis. Accordingly, a multicentric placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial, the REVIDAH study, has been launched to analyze whether a vitamin D supplement improves clinical outcomes in patients with PAH (Fig. 1).

FundingThe work in the authors’ laboratories is funded by the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (PID2019-104867RB-I00), the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ICI23/00001), and by Fundación contra la hipertensión pulmonar (FCHP).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.