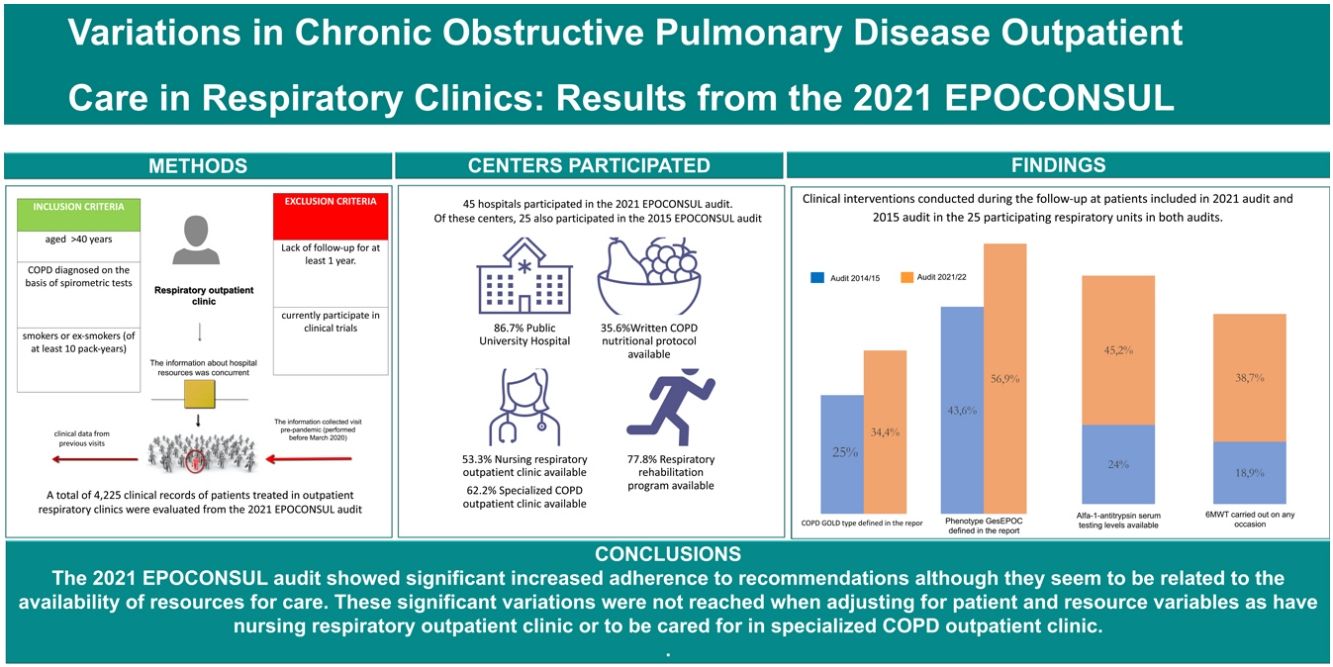

The aim of our work has been to describe the results of the clinical audit carried out in 2021 and to compare the results with 2015 EPOCONSUL audit.

MethodsEPOCONSUL 2021 is a cross-sectional audit that evaluated the outpatient care provided to patients with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in respiratory clinics in Spain with prospective recruitment between April 15, 2021, and January 31, 2022.

ResultsA total of 45 hospitals participated in the 2021 audit and 4.225 clinical records of patients were evaluated. Clinical phenotype according to the Spanish National Guidelines for COPD care (GesEPOC) was reported in 63.1% of the audited patients, and the COPD type assessment for the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) was present in 38.3%. There was an improved compliance with clinical practice guideline (CPG) recommendations in the 2021 audit with respect to the 2015 audit. There was an increase in the proportion of cases with alfa-1-antitrypsin serum level testing available (audit 1: 18.9%; audit 2: 38.7%, p<0.001) and 6-min walk test carried out (audit 1: 24%; audit 2: 45.2%, p<0.001). However, these significant variations adherence to CPG recommendations were not reached for the clinical evaluation and therapeutic intervention category when adjusting for patient and resource variables.

ConclusionsThe 2021 EPOCONSUL audit showed increased adherence to recommendations although they seem to be related to the availability of resources for care. These results should be taken into account in order to establish improvements in resources to achieve a better quality of care.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a public health problem of primary importance due to its elevated prevalence and mortality.1–3 It is one of the most frequent reasons for seeking medical attention, accounting for 10% of primary care consultations and 30% of outpatient pulmonology consultations in Spain,4 and it is responsible for a significant economic cost and a high socio-economic burden on society. There are numerous CPG and strategy documents addressing the management of COPD.5–7 However, extensive evidence shows that there is a gap between the healthcare that patients receive and guideline recommendations.8–10

Clinical audits have emerged as a potential tool to summarize the clinical performance of healthcare and to provide health professionals with information that they can use to assess and adjust their performance, thus improving the clinical care provided to patients and the clinical outcomes.11 Systematic review has suggested that clinical audits are associated with small yet meaningful improvements in professional practice,12 and the effects are greater where existing practice is less in line with what is desired and is inconsistent with that of the practitioner's peers or accepted CPGs.13 Other factors such as the type of intervention (audit and feedback alone, or coupled with multifaceted interventions), motivation (link to economic incentives or being used in accreditation or organizational assessments) and greater intensity (frequency and duration of feedback) are important in explaining differences in the effects of audits and feedback across different studies.14

In this context, Spain has used an auditing process that evaluated outpatient care provided to patients with COPD in respiratory clinics in Spain, called EPOCONSUL,8 which has resulted in the completion of two clinical audits based on available data from medical registries. The first of these audits was performed between May 1, 2014, and May 1, 2015, and the second between April 15, 2021, and January 31, 2022.

The objective of our work has been to describe the results of the clinical audit performed between April 15, 2021, and January 31, 2022, and to compare medical care for patients with COPD in outpatient clinics in both audits.

MethodologyThe methodology of the 2021 EPOCONSUL audit is similar to that of the 2015 EPOCONSUL audit that has been reported in previous publications.8,9 Briefly, the COPD audit promoted by the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) was designed to evaluate clinical practice as well as clinical and organizational factors related to managing patients with COPD across Spain. It was designed as an observational non-interventional cross-sectional study.

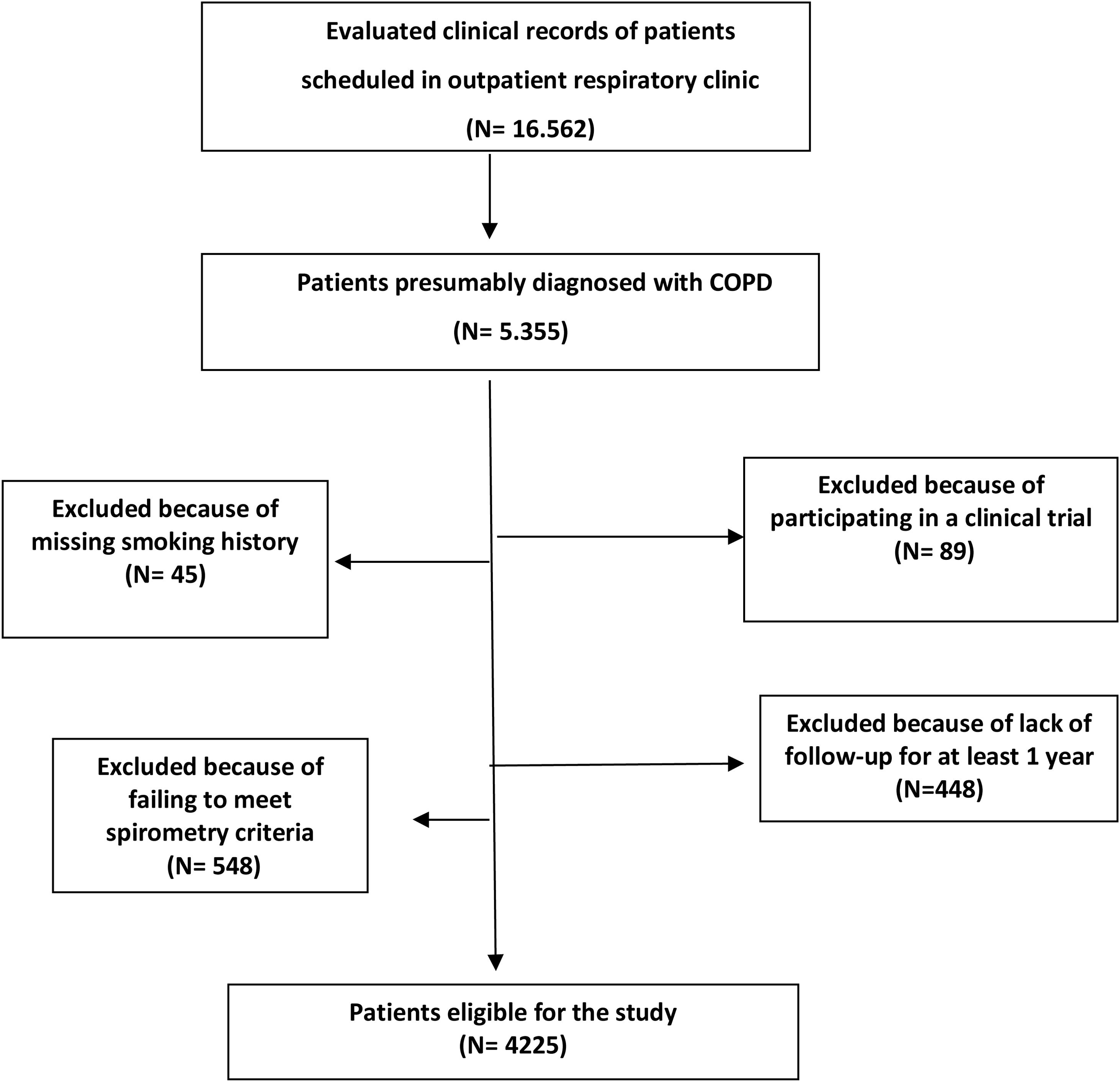

Recruitment was intermittent; every month, each investigator recruited the clinical records of the first 10 patients identified as being diagnosed with COPD that were seen in the outpatient respiratory clinic. Subsequently, the patients identified were reevaluated to determine if they met the inclusion/exclusion criteria described in Appendix 1. The sampling process was detailed in an epidemiology flow chart and described in Fig. 1.

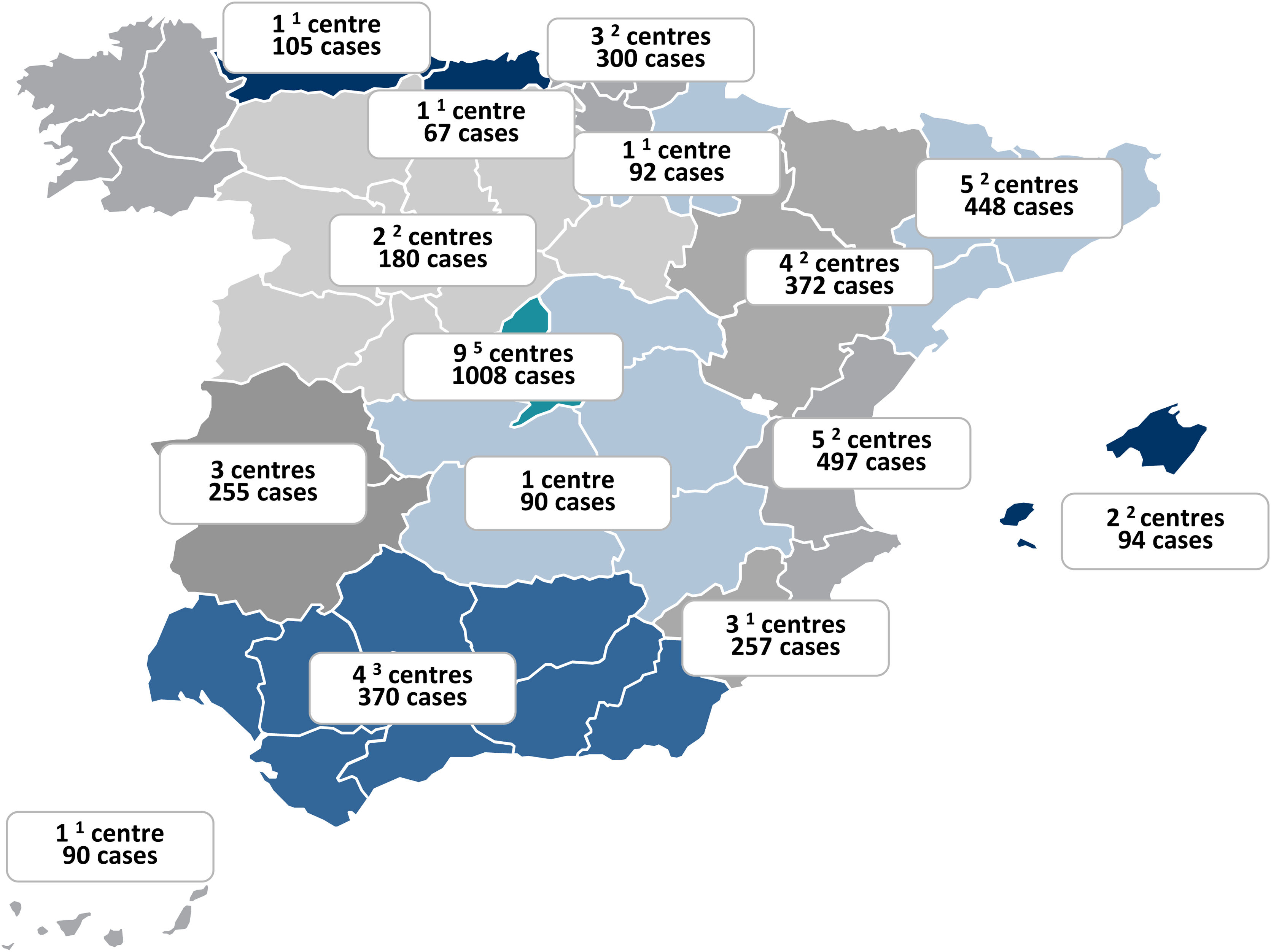

The Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery sent an official invitation to participate in the study to all the respiratory units in Spain with outpatient respiratory clinics according to the Registry of the Ministry of Health and to the register of members of the SEPAR. From the 189 centers invited, 45 pulmonology services or sections participated (23.8%). The distribution of hospitals and patient records that participated in 2021 audit in the different regions are shown in Fig. 2. Participating investigators in 2021 EPOCONSUL are included in Appendix 2.

The information collected was historical in nature for the clinical data from the last visit pre-pandemic (performed before March 2020) and previous visits, and the information about hospital resources was concurrent and is described in Appendix 3.

As described in previous publications on the EPOCONSUL audit process,8,9 in order to evaluate the degree of current implementation of the main CPG statements according to GesEPOC and GOLD, we classified the recommendations (GesEPOC and GOLD) evaluated in the study into 3 categories: clinical evaluation, disease evaluation and therapeutic interventions. We established fulfilling more than 50% of the criteria for good clinical practice evaluated in each category as the cut-off point. The number of criteria for good clinical practice met in each category was analyzed in the patients evaluated in each audit.

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain; internal code 20/722-E). Additionally, according to current research laws in Spain, the ethics committee at each participating hospital evaluated and agreed to the study protocol. The need for informed consent was waived because ours is a clinical audit, in addition to the non-interventional nature of the study, the anonymization of data and the need to blindly evaluate clinical performance. This circumstance was clearly explained in the protocol, and the ethics committees approved this procedure. To avoid modifications to the usual clinical practice and preserve the blinding of the clinical performance evaluation, the medical staff responsible for the outpatient respiratory clinic was not informed about the audit. Data was entered remotely at each participating location to a centrally controlled server.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were summarized by their frequency distribution and quantitative variables by their median and interquartile range. The differences between the two audits were evaluated regarding both hospital resources and patient characteristics. χ2 tests were used for categorical data, while the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used for continuous data.

Three dependent variables were generated to evaluate the degree of CPG implementation; the criteria for good clinical practice were categorized into: fulfilling more than three criteria in the clinical evaluation, fulfilling more than four criteria in the COPD evaluation, and fulfilling more than three criteria in the therapeutic intervention. In respiratory units that participated in both audits, the association between the two audits (reference audit 1) and each of the dependent variables was assessed by calculating the adjusted odds ratio (OR) via multilevel logistic regression analysis. Each multilevel analysis included two levels: the individual or patient level (level 1), and the hospital level (level 2). Candidate adjustment variables (patient characteristics and hospital resources) with a value of p<0.05 in the analysis of the differences between the two audits and/or those identified as predictors of the dependent variables in previous studies were included in the multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was assumed as p<0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata software version 17 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

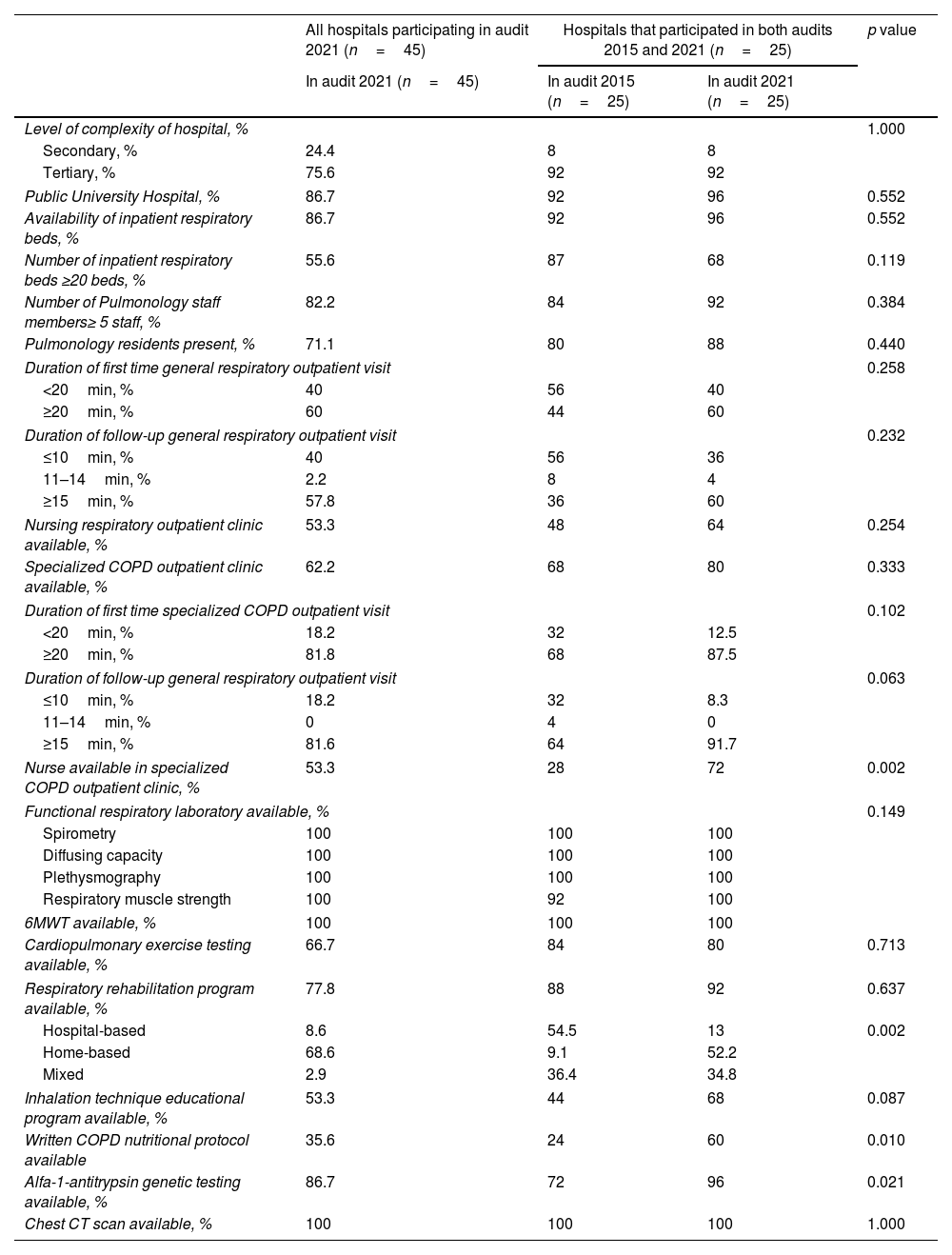

ResultsA total of 45 hospitals participated in the 2021 EPOCONSUL audit. Of these centers, 25 also participated in the 2015 EPOCONSUL audit. The main characteristics of the participating centers and the resource comparison with the 2015 audit of the respiratory units that participated in both audits are summarized in Table 1. The participating hospitals were largely tertiary-level and public university hospitals, and a high proportion had a pulmonary resident. The availability of a specialized COPD outpatient clinic (audit 1: 68%; audit 2: 80%, p=0.333), outpatient respiratory nursing clinic (audit 1: 48%; audit 2: 64%, p=0.254), and an inhalation technique educational program (audit 1: 44%; audit 2: 68%, p=0.087) was higher but not statistically significant. A higher proportion of patients were cared for in a specialized COPD outpatient clinic (audit 1: 35.5%; audit 2: 53.9%, p<0.001). The availability of a nurse in a specialized COPD outpatient clinic (audit 1: 28%; audit 2: 72%, p=0.002), a written COPD nutritional protocol (audit 1: 24%; audit 2: 60%, p=0.010) and alfa-1-antitrypsin genetic testing (audit 1: 72%; audit 2: 96%, p=0.021) significantly improved in the second audit.

Characteristics and resources of the participating respiratory units.

| All hospitals participating in audit 2021 (n=45) | Hospitals that participated in both audits 2015 and 2021 (n=25) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In audit 2021 (n=45) | In audit 2015 (n=25) | In audit 2021 (n=25) | ||

| Level of complexity of hospital, % | 1.000 | |||

| Secondary, % | 24.4 | 8 | 8 | |

| Tertiary, % | 75.6 | 92 | 92 | |

| Public University Hospital, % | 86.7 | 92 | 96 | 0.552 |

| Availability of inpatient respiratory beds, % | 86.7 | 92 | 96 | 0.552 |

| Number of inpatient respiratory beds ≥20 beds, % | 55.6 | 87 | 68 | 0.119 |

| Number of Pulmonology staff members≥ 5 staff, % | 82.2 | 84 | 92 | 0.384 |

| Pulmonology residents present, % | 71.1 | 80 | 88 | 0.440 |

| Duration of first time general respiratory outpatient visit | 0.258 | |||

| <20min, % | 40 | 56 | 40 | |

| ≥20min, % | 60 | 44 | 60 | |

| Duration of follow-up general respiratory outpatient visit | 0.232 | |||

| ≤10min, % | 40 | 56 | 36 | |

| 11–14min, % | 2.2 | 8 | 4 | |

| ≥15min, % | 57.8 | 36 | 60 | |

| Nursing respiratory outpatient clinic available, % | 53.3 | 48 | 64 | 0.254 |

| Specialized COPD outpatient clinic available, % | 62.2 | 68 | 80 | 0.333 |

| Duration of first time specialized COPD outpatient visit | 0.102 | |||

| <20min, % | 18.2 | 32 | 12.5 | |

| ≥20min, % | 81.8 | 68 | 87.5 | |

| Duration of follow-up general respiratory outpatient visit | 0.063 | |||

| ≤10min, % | 18.2 | 32 | 8.3 | |

| 11–14min, % | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| ≥15min, % | 81.6 | 64 | 91.7 | |

| Nurse available in specialized COPD outpatient clinic, % | 53.3 | 28 | 72 | 0.002 |

| Functional respiratory laboratory available, % | 0.149 | |||

| Spirometry | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Diffusing capacity | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Plethysmography | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Respiratory muscle strength | 100 | 92 | 100 | |

| 6MWT available, % | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Cardiopulmonary exercise testing available, % | 66.7 | 84 | 80 | 0.713 |

| Respiratory rehabilitation program available, % | 77.8 | 88 | 92 | 0.637 |

| Hospital-based | 8.6 | 54.5 | 13 | 0.002 |

| Home-based | 68.6 | 9.1 | 52.2 | |

| Mixed | 2.9 | 36.4 | 34.8 | |

| Inhalation technique educational program available, % | 53.3 | 44 | 68 | 0.087 |

| Written COPD nutritional protocol available | 35.6 | 24 | 60 | 0.010 |

| Alfa-1-antitrypsin genetic testing available, % | 86.7 | 72 | 96 | 0.021 |

| Chest CT scan available, % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.000 |

Data are represented as percentages. 6MWT: 6-min walk test; CT, computerized tomography.

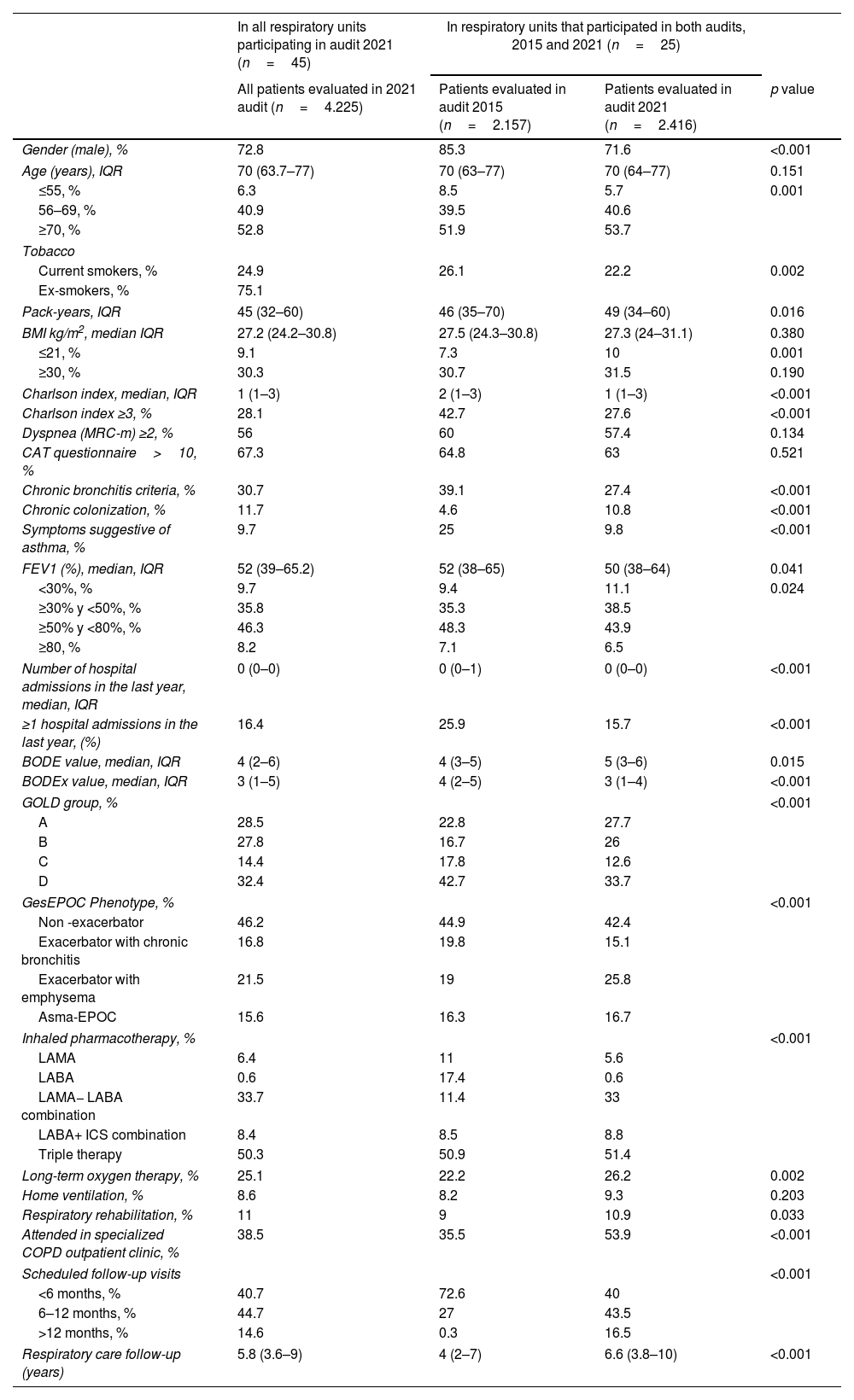

A total of 4225 clinical records of patients treated in outpatient respiratory clinics were evaluated from the 2021 EPOCONSUL audit. The characteristics of the patients evaluated in 2021 audit and their comparison with patients evaluated in the 2015 audit of the respiratory units that participated in both audits are summarized in Table 2. The cases were mostly male, although this percentage decreased significantly in the second audit (audit 1: 85.3%; audit 2: 71.6%, p<0.001). There were some statistically significant differences in Charlson index ≥3 (audit 1: 42.7%; audit 2: 27.6%, p<0.001), ≥1 hospital admissions in the last year (audit 1: 25.9%; audit 2: 15.7%, p<0.001) and FEV1<50% (audit 1: 44.6%%; audit 2: 49.6%, p<0.002).

Characteristics of the patients evaluated in 2021 audit and their comparison with patients evaluated in the 2015 audit of the respiratory units that participated in both audits.

| In all respiratory units participating in audit 2021 (n=45) | In respiratory units that participated in both audits, 2015 and 2021 (n=25) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients evaluated in 2021 audit (n=4.225) | Patients evaluated in audit 2015 (n=2.157) | Patients evaluated in audit 2021 (n=2.416) | p value | |

| Gender (male), % | 72.8 | 85.3 | 71.6 | <0.001 |

| Age (years), IQR | 70 (63.7–77) | 70 (63–77) | 70 (64–77) | 0.151 |

| ≤55, % | 6.3 | 8.5 | 5.7 | 0.001 |

| 56–69, % | 40.9 | 39.5 | 40.6 | |

| ≥70, % | 52.8 | 51.9 | 53.7 | |

| Tobacco | ||||

| Current smokers, % | 24.9 | 26.1 | 22.2 | 0.002 |

| Ex-smokers, % | 75.1 | |||

| Pack-years, IQR | 45 (32–60) | 46 (35–70) | 49 (34–60) | 0.016 |

| BMI kg/m2, median IQR | 27.2 (24.2–30.8) | 27.5 (24.3–30.8) | 27.3 (24–31.1) | 0.380 |

| ≤21, % | 9.1 | 7.3 | 10 | 0.001 |

| ≥30, % | 30.3 | 30.7 | 31.5 | 0.190 |

| Charlson index, median, IQR | 1 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | <0.001 |

| Charlson index ≥3, % | 28.1 | 42.7 | 27.6 | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea (MRC-m) ≥2, % | 56 | 60 | 57.4 | 0.134 |

| CAT questionnaire>10, % | 67.3 | 64.8 | 63 | 0.521 |

| Chronic bronchitis criteria, % | 30.7 | 39.1 | 27.4 | <0.001 |

| Chronic colonization, % | 11.7 | 4.6 | 10.8 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms suggestive of asthma, % | 9.7 | 25 | 9.8 | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (%), median, IQR | 52 (39–65.2) | 52 (38–65) | 50 (38–64) | 0.041 |

| <30%, % | 9.7 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 0.024 |

| ≥30% y <50%, % | 35.8 | 35.3 | 38.5 | |

| ≥50% y <80%, % | 46.3 | 48.3 | 43.9 | |

| ≥80, % | 8.2 | 7.1 | 6.5 | |

| Number of hospital admissions in the last year, median, IQR | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 hospital admissions in the last year, (%) | 16.4 | 25.9 | 15.7 | <0.001 |

| BODE value, median, IQR | 4 (2–6) | 4 (3–5) | 5 (3–6) | 0.015 |

| BODEx value, median, IQR | 3 (1–5) | 4 (2–5) | 3 (1–4) | <0.001 |

| GOLD group, % | <0.001 | |||

| A | 28.5 | 22.8 | 27.7 | |

| B | 27.8 | 16.7 | 26 | |

| C | 14.4 | 17.8 | 12.6 | |

| D | 32.4 | 42.7 | 33.7 | |

| GesEPOC Phenotype, % | <0.001 | |||

| Non -exacerbator | 46.2 | 44.9 | 42.4 | |

| Exacerbator with chronic bronchitis | 16.8 | 19.8 | 15.1 | |

| Exacerbator with emphysema | 21.5 | 19 | 25.8 | |

| Asma-EPOC | 15.6 | 16.3 | 16.7 | |

| Inhaled pharmacotherapy, % | <0.001 | |||

| LAMA | 6.4 | 11 | 5.6 | |

| LABA | 0.6 | 17.4 | 0.6 | |

| LAMA− LABA combination | 33.7 | 11.4 | 33 | |

| LABA+ ICS combination | 8.4 | 8.5 | 8.8 | |

| Triple therapy | 50.3 | 50.9 | 51.4 | |

| Long-term oxygen therapy, % | 25.1 | 22.2 | 26.2 | 0.002 |

| Home ventilation, % | 8.6 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 0.203 |

| Respiratory rehabilitation, % | 11 | 9 | 10.9 | 0.033 |

| Attended in specialized COPD outpatient clinic, % | 38.5 | 35.5 | 53.9 | <0.001 |

| Scheduled follow-up visits | <0.001 | |||

| <6 months, % | 40.7 | 72.6 | 40 | |

| 6–12 months, % | 44.7 | 27 | 43.5 | |

| >12 months, % | 14.6 | 0.3 | 16.5 | |

| Respiratory care follow-up (years) | 5.8 (3.6–9) | 4 (2–7) | 6.6 (3.8–10) | <0.001 |

Data are represented as percentages or median (IQR: interquartile range); LABA: long-acting beta-2 agonists; LAMA: long-acting antimuscarinic agents; CSI: inhaled corticosteroids; Triple therapy: LAMA+LABA+CSI; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; GesEPOC: Spanish National Guideline for COPD; CAT: COPD Assessment Test.

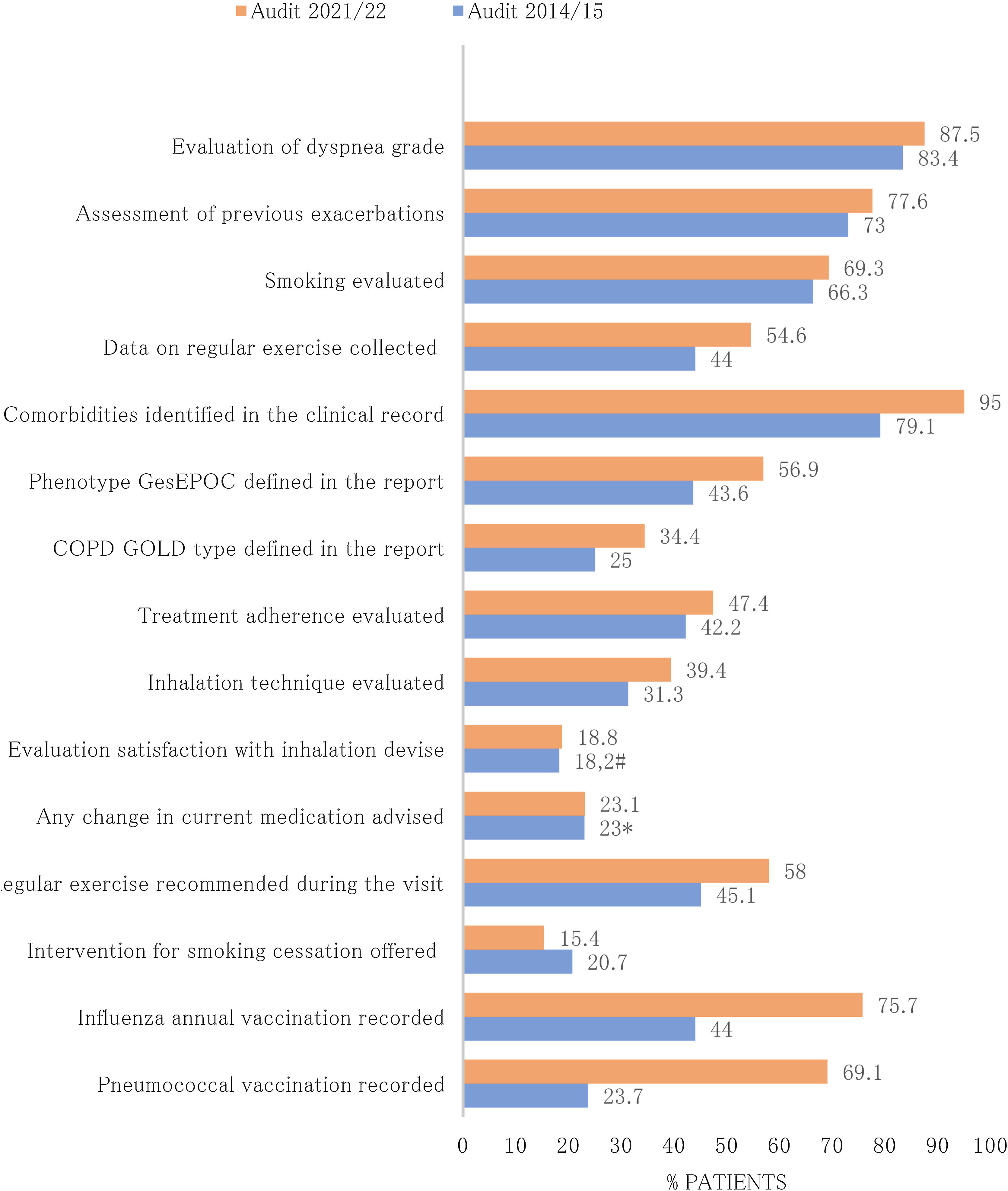

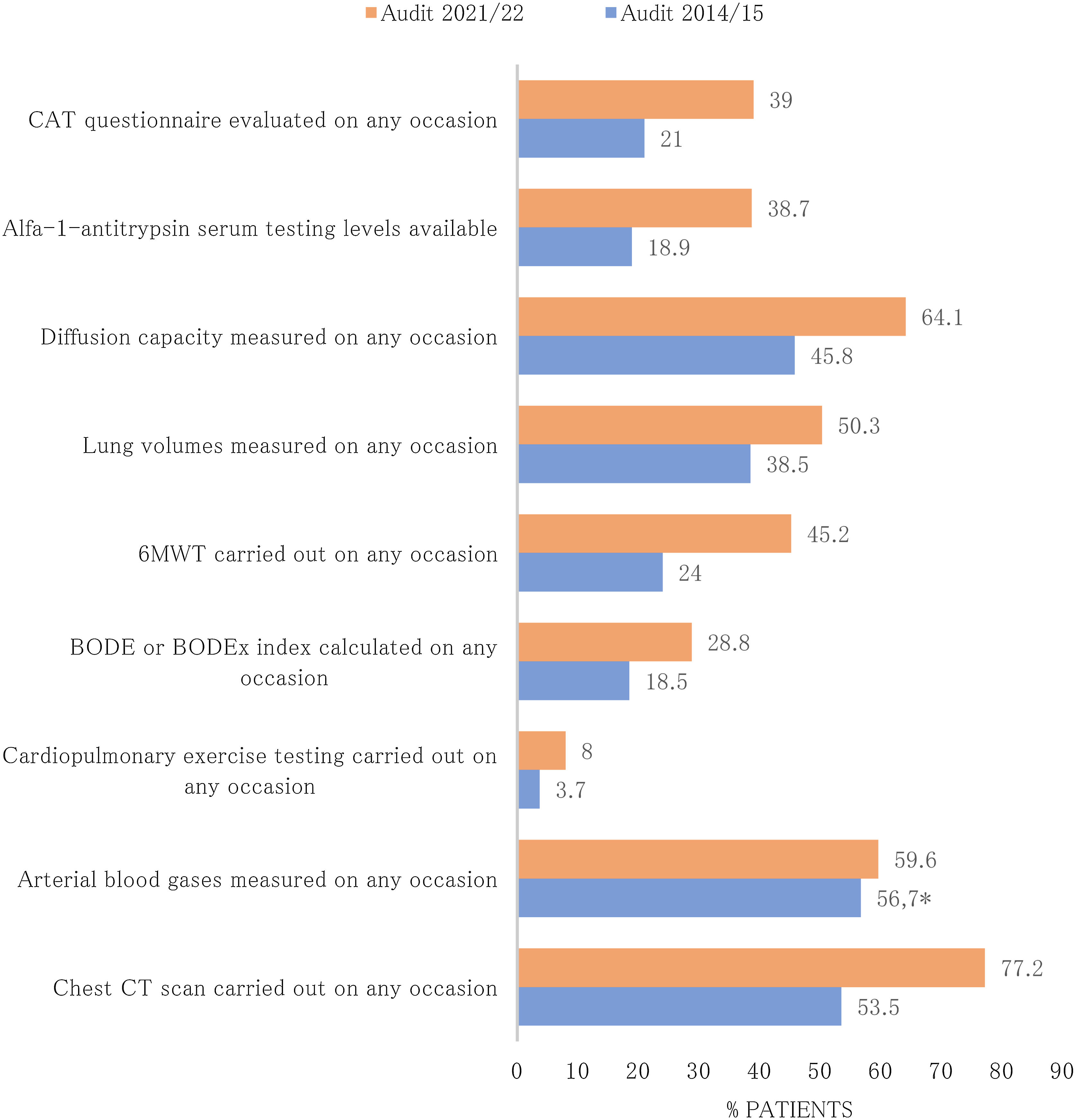

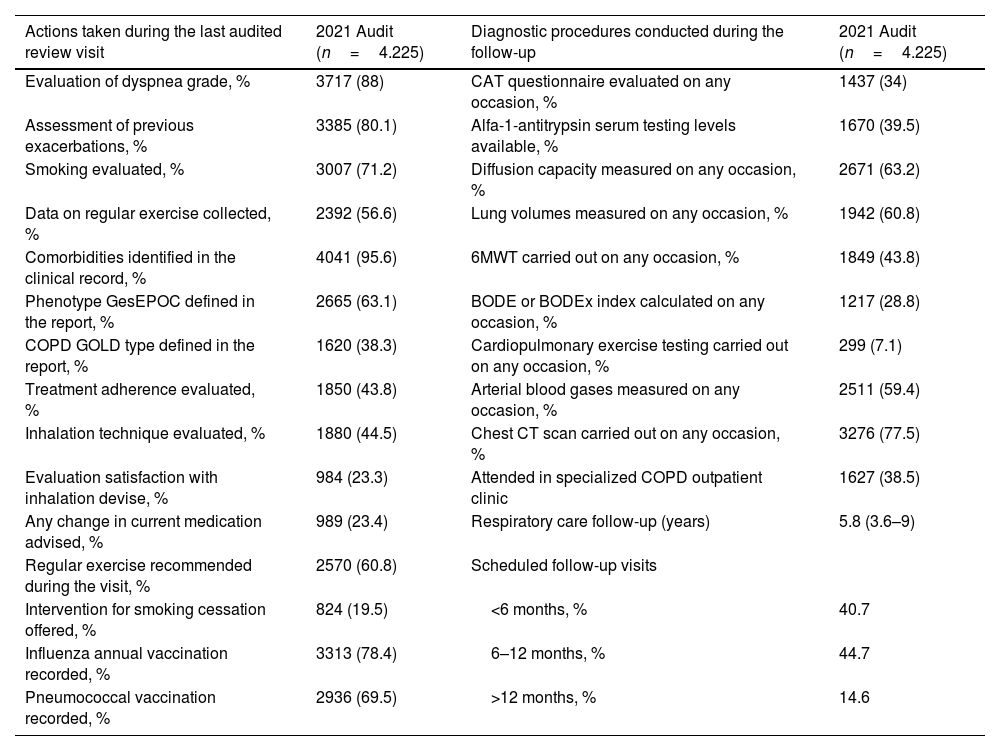

Diagnostic procedures performed during the follow-up and actions carried out in the last review visit recorded in EPOCONSUL 2021 are summarized in Table 3. Most of the interventions assessed were most frequently carried out in audit 2. The proportion of cases where COPD phenotype according to GesEPOC was evaluated (audit 1: 43.6%; audit 2: 56.9%, p<0.001), where inhalation technique was evaluated (audit 1: 31.3%; audit 2: 39.4%, p<0.001), and where data on regular exercise was collected (audit 1: 44%; audit 2: 54.6%, p<0.001) significantly increased in the second audit. The proportion of cases with alfa-1-antitrypsin serum level testing available (audit 1: 18.9%; audit 2: 38.7%, p<0.001), diffusion capacity measured (audit 1: 45.8%; audit 2: 64.1%, p<0.001), and 6-min walk test carried out (audit 1: 24%; audit 2: 45.2%, p<0.001) significantly increased in the second audit. The actions carried out in the last review visit and diagnostic procedures performed during the follow-up in both audits are shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

Interventions performed at patients included in 2021 audit.

| Actions taken during the last audited review visit | 2021 Audit (n=4.225) | Diagnostic procedures conducted during the follow-up | 2021 Audit (n=4.225) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of dyspnea grade, % | 3717 (88) | CAT questionnaire evaluated on any occasion, % | 1437 (34) |

| Assessment of previous exacerbations, % | 3385 (80.1) | Alfa-1-antitrypsin serum testing levels available, % | 1670 (39.5) |

| Smoking evaluated, % | 3007 (71.2) | Diffusion capacity measured on any occasion, % | 2671 (63.2) |

| Data on regular exercise collected, % | 2392 (56.6) | Lung volumes measured on any occasion, % | 1942 (60.8) |

| Comorbidities identified in the clinical record, % | 4041 (95.6) | 6MWT carried out on any occasion, % | 1849 (43.8) |

| Phenotype GesEPOC defined in the report, % | 2665 (63.1) | BODE or BODEx index calculated on any occasion, % | 1217 (28.8) |

| COPD GOLD type defined in the report, % | 1620 (38.3) | Cardiopulmonary exercise testing carried out on any occasion, % | 299 (7.1) |

| Treatment adherence evaluated, % | 1850 (43.8) | Arterial blood gases measured on any occasion, % | 2511 (59.4) |

| Inhalation technique evaluated, % | 1880 (44.5) | Chest CT scan carried out on any occasion, % | 3276 (77.5) |

| Evaluation satisfaction with inhalation devise, % | 984 (23.3) | Attended in specialized COPD outpatient clinic | 1627 (38.5) |

| Any change in current medication advised, % | 989 (23.4) | Respiratory care follow-up (years) | 5.8 (3.6–9) |

| Regular exercise recommended during the visit, % | 2570 (60.8) | Scheduled follow-up visits | |

| Intervention for smoking cessation offered, % | 824 (19.5) | <6 months, % | 40.7 |

| Influenza annual vaccination recorded, % | 3313 (78.4) | 6–12 months, % | 44.7 |

| Pneumococcal vaccination recorded, % | 2936 (69.5) | >12 months, % | 14.6 |

Data are expressed as absolute (relative) frequencies (%) or median (IQR: interquartile range).

Abbreviations: GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; GesEPOC: Spanish National Guideline for COPD; CAT: COPD Assessment Test; 6MWT: 6-min walk test; CT: computerized tomography.

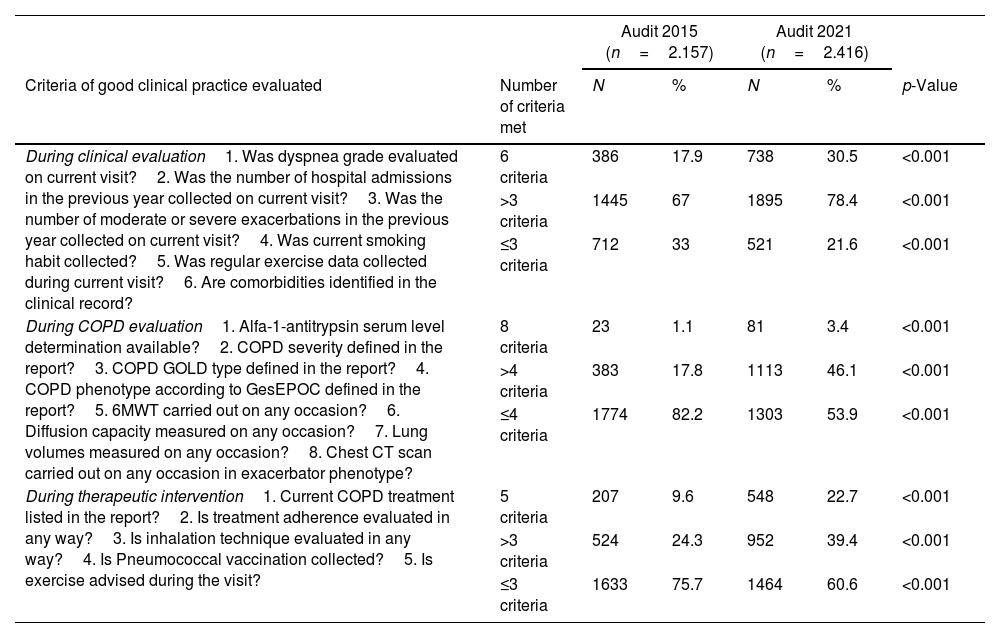

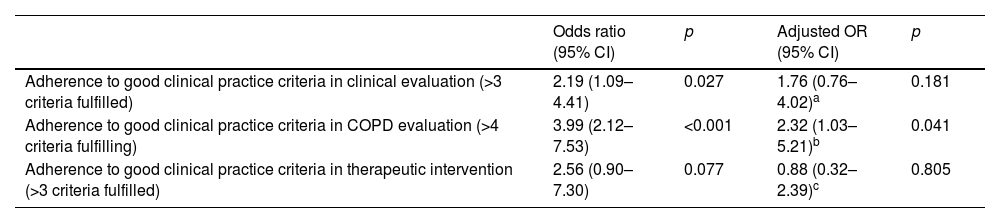

Adherence to the main CPG recommendations in EPOCONSUL 2021 and their comparison with the 2015 audit is summarized in Table 4. There was a significant variation between the audits, with a better adherence to CPG recommendation statements by category (clinical evaluation of the patient, COPD evaluation and therapeutic intervention) in audit 2. In the adjusted model, the inclusion of resource, model of care in specialized COPD consultations and patient related factors reduced the difference in meeting in the improvement of good clinical practice compliance criteria evaluated in each category between the two audits, and the adjusted effect was not significant, as shown in Table 5.

Changes in adherence to recommendations (GOLD and GesEPOC) in both audits. Number of criteria of good clinical practice met in each category in patients evaluated in the 25 respiratory units that participated in both audits, 2015 and 2021.

| Audit 2015 (n=2.157) | Audit 2021 (n=2.416) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria of good clinical practice evaluated | Number of criteria met | N | % | N | % | p-Value |

| During clinical evaluation1. Was dyspnea grade evaluated on current visit?2. Was the number of hospital admissions in the previous year collected on current visit?3. Was the number of moderate or severe exacerbations in the previous year collected on current visit?4. Was current smoking habit collected?5. Was regular exercise data collected during current visit?6. Are comorbidities identified in the clinical record? | 6 criteria | 386 | 17.9 | 738 | 30.5 | <0.001 |

| >3 criteria | 1445 | 67 | 1895 | 78.4 | <0.001 | |

| ≤3 criteria | 712 | 33 | 521 | 21.6 | <0.001 | |

| During COPD evaluation1. Alfa-1-antitrypsin serum level determination available?2. COPD severity defined in the report?3. COPD GOLD type defined in the report?4. COPD phenotype according to GesEPOC defined in the report?5. 6MWT carried out on any occasion?6. Diffusion capacity measured on any occasion?7. Lung volumes measured on any occasion?8. Chest CT scan carried out on any occasion in exacerbator phenotype? | 8 criteria | 23 | 1.1 | 81 | 3.4 | <0.001 |

| >4 criteria | 383 | 17.8 | 1113 | 46.1 | <0.001 | |

| ≤4 criteria | 1774 | 82.2 | 1303 | 53.9 | <0.001 | |

| During therapeutic intervention1. Current COPD treatment listed in the report?2. Is treatment adherence evaluated in any way?3. Is inhalation technique evaluated in any way?4. Is Pneumococcal vaccination collected?5. Is exercise advised during the visit? | 5 criteria | 207 | 9.6 | 548 | 22.7 | <0.001 |

| >3 criteria | 524 | 24.3 | 952 | 39.4 | <0.001 | |

| ≤3 criteria | 1633 | 75.7 | 1464 | 60.6 | <0.001 | |

Data are represented as percentages. GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; GesEPOC: Spanish National Guideline for COPD; CT: computerized tomography.

Multilevel logistic regression models of the variations in adherence to good clinical practice criteria for 3 categories between the 2 audits.

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence to good clinical practice criteria in clinical evaluation (>3 criteria fulfilled) | 2.19 (1.09–4.41) | 0.027 | 1.76 (0.76–4.02)a | 0.181 |

| Adherence to good clinical practice criteria in COPD evaluation (>4 criteria fulfilling) | 3.99 (2.12–7.53) | <0.001 | 2.32 (1.03–5.21)b | 0.041 |

| Adherence to good clinical practice criteria in therapeutic intervention (>3 criteria fulfilled) | 2.56 (0.90–7.30) | 0.077 | 0.88 (0.32–2.39)c | 0.805 |

In clinical evaluation: Effect adjusted for variables: outpatient respiratory nursing clinic availability, specialized COPD outpatient clinic available, being treated in specialized COPD outpatient clinic, number of hospital admissions in the last year≥1, and FEV1<50%.

in COPD evaluation: Effect adjusted for variables: outpatient respiratory nursing clinic availability, specialized COPD outpatient clinic available, alfa-1-antitrypsin genetic testing available, being treated in specialized COPD outpatient clinic, number of hospital admissions in the last year≥1, and FEV1<50%.

In therapeutic intervention: Effect adjusted for variables: outpatient respiratory nursing clinic availability, specialized COPD outpatient clinic available, inhalation technique educational program available, number of hospital admissions in the last year≥1, FEV1<50%, and being treated in specialized COPD outpatient clinic.

This study describes the status of COPD care in outpatient respiratory clinics in Spain and assesses variations in care and resources compared to the 2015 audit. Our key messages are that we have observed improvements in outpatient care provided in respiratory clinics with greater adherence to good clinical practice recommendations, although this increase lost significance when adjusted for factors related to the resources of the center or care model, which could indicate that interventions are related to the availability of certain resources in the units and care model where the patient is seen.

In terms of available resources, it should be noted that only approximately half of the respiratory units have nursing respiratory outpatient clinic and inhalation technique educational program available despite the fact that the majority of hospitals were tertiary care centers. Specialized COPD outpatient clinic was present in 62% of the centers. This healthcare model in COPD has been developed in recent years to offer improved care and optimization of recourses4,15 in line with current guidelines established in COPD action plans for patients with a high degree of intervention and greater complexity.5,6 Comparison of the resources of the respiratory units of the 25 centers that participated in both audits showed no significant differences between the two audits, except there was a greater availability of nurse in specialized COPD outpatient clinic, alpha-1-antitrypsin genetic testing, written COPD nutritional protocol or community rehabilitation program in 2021 audit.

Regarding the characteristics of the cases evaluated in both audits, there were significant differences in sex, with a higher frequency of women in the second audit (28.4% vs. 14.7%, p<0.001). This is justified by the fact that COPD is an increasingly prevalent disease in women according to data from the EPISCAN II study, whose analysis by community showed that the prevalence of COPD is higher in women than in men in the community of Madrid.2 Significant differences were also found, with a lower burden of comorbidity, history of exacerbations, and active smoking in the cases evaluated in the second audit, but with increased severity in the degree of airflow obstruction.

Clinical audits have traditionally been used in healthcare as a tool to collect information about the care provided and, consequently, as a quality improvement process. They help to identify problem areas and provide valuable information for health professionals and health service managers, both of whom are focused on achieving clinical practice that meets quality standards. Communication of their results to health professionals has been seen as a strategy for self-correction of their clinical practice.16,17 However, national audits have traditionally been perceived by clinicians as a data collection exercise to produce reports for national use, often with limited local value. This has sometimes been facilitated by the fact that publications of results come later, long after data collection. As a result, data can be perceived as outdated and irrelevant to current practice. In this sense, our audit process was cross-sectional with an interval of 5 years between the two audits, although throughout this time period, there were numerous communications of results, presentation meetings and discussion of the findings of the first audit. In addition, during this period between the two audits, several updates to good clinical practice guidelines (GesEPOC and GOLD)6,18 and strategic documents on COPD management19 were published, with an extensive dissemination plan for good clinical practice recommendations, aiming to improve the quality of care, with special emphasis on areas of deficiency based on the results of the first audit.

Clinical audits are a key component of quality improvement programs, and systematic reviews have suggested that clinical audits are associated with small but significant improvements in professional practice.12,20,21

Previous studies have shown that adherence to clinical guidelines was a strong predictor of a favorable outcome. Roberts et al.22 have suggested that a hospital's resources are potential components of the unexplained variation in outcomes. A greater number of medical and nursing staff was identified as a protective factor for intra-hospital mortality. In AUDIPOC Spain,23 the large hospital COPD volume and the number of patients with COPD admitted to the hospital the year prior to admission was identified as a predictor of a favorable outcome. Also, in EPOCONSUL Spain, clinics’ control of COPD was more common in specialized COPD clinics in Spain.24

Our results identify relevant improvements in the clinical assessment of patients. Adherence to recommendations such as the assessment of the degree of dyspnea and previous exacerbations, the recording of daily physical activity and smoking data, and the identification of comorbidities in the report increased in the second audit. This variation in our clinical practice is in line with current GesEPOC and GOLD recommendations that establish defining the level of risk and the level of control in visits as a key step in the care of patients with COPD.5,6

In our analysis, there was also greater adherence in the second audit to recommendations such as performing computed axial tomography in frequent exacerbators, identifying the GOLD risk level or the clinical phenotype according to GesEPOC, and analyzing lung function (lung volumes, diffusion test or gait test). This increase in diagnostic testing responds to the recommendation for further characterization of COPD in high-risk patients in order to identify treatable features to improve clinical outcomes and minimize side effects, as well as their prognostic value.5 Other procedures that were inconsistent with the accepted CPGs in the first audit, such as the CAT questionnaire, the determination of alpha-1-antitrypsin in blood, and the evaluation of the BODE or BODEX index, increased significantly in the second audit.

In our analysis, when assessing variations in therapeutic interventions, we found an increase in the assessment of inhalation technique and healthy habits such as recommending regular physical activity and preventive vaccination measures.

However, these significant variations adherence to good clinical practice recommendations were not reached when adjusting for patient and resource variables as have nursing respiratory outpatient clinic or to be cared for in specialized COPD outpatient clinic. These results suggest a possible relationship between better adherence to recommendations and a greater availability of specific resources to carry them out. These results should be taken into account by health professionals and administrations in order to establish improvements in resources to achieve better clinical practice in these areas.

Several systematic reviews have assessed the effectiveness of audits and feedback and found that they are more likely to be beneficial when existing practice is less in line with what is desired.13 Other factors that have been shown to influence effectiveness and may explain differences in the effects of audits and feedback between different studies14,16,17 are motivation (linkage to financial incentives or being used in accreditation or organizational evaluations) and higher intensity (frequency and duration of feedback).

Our study has several limitations. The main limitation to be taken into account is the fact that the selection of participating centers in both audits was not random and the participation of hospitals was voluntary based on their previous experience in COPD clinical studies and their interest in participating. Therefore, the results cannot be considered representative of the national population with COPD and, furthermore, the results of our audit process could show the best picture of resources, COPD care delivery and the impact of feedback on health professionals, if we consider that two thirds of the participating facilities are tertiary hospitals, and that motivation to participate may be a factor influencing the effect of the audit and feedback.

We should also remember that every clinical audit has an intrinsic limitation of missing values (not available) in spite of the inclusion methodology and periodic supervision of the database. Despite these limitations, we believe that this dataset represents the largest available comparative survey of Spanish centers.

ConclusionsThe 2021 EPOCONSUL audit showed increased adherence to recommendations although they seem to be related to the availability of resources for care. These results should be taken into account in order to establish improvements in resources to achieve a better quality of care.

Authors’ contributionsMCR, JJLC, MM, JJSC, BAN and JLRH form the study's Scientific Committee and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. MEFF did the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to data analysis, results interpretation, drafting and revising the paper, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statementThe study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Clinical Ethics Committee at the Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain; internal code 20/722-E).

Data availability statementThe data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

FundingThis study has been promoted and sponsored by the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR). We thank Chiesi for its financial support in carrying out the study. The financing entities did not participate in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, publication, or preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestsMCR has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Chiesi, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, and Grifols, and consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Bial. JLLC has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for: AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Ferrer, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Menarini, Megalabs, Novartis and Rovi. MM has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, Menarini, Kamada, Takeda, Zambon, CSL Behring, Specialty Therapeutics, Janssen, Grifols and Novartis, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Atriva Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, CSL Behring, Inhibrx, Ferrer, Menarini, Mereo Biopharma, Spin Therapeutics, ONO Pharma, Palobiofarma SL, Takeda, Novartis, and Grifols and research grants from Grifols. JJSC has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, FAES, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini and Novartis, and consulting fees from Bial, Chiesi and GSK, and grants from GSK. BAN reports grants and personal fees from GSK, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees and non-financial support from Chiesi, non-financial support from Laboratorios Menarini, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Gilead, personal fees and non-financial support from MSD, personal fees from Laboratorios BIAL, personal fees from Zambon, outside the submitted work; in addition, Dr. Alcázar-Navarrete has a patent P201730724 issued. JLRH has received speaker fees from Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Zambon and Grifols, and consulting fees from Bial.

The authors thank the investigators and centers that participated in the EPOCONSUL study (Appendix 2).