Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is one of the first recognized interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), having been described as early as 1700. The etiopathogenesis of HP is based on repeated exposure to an occult source of inducers in genetically predisposed individuals. Both fibrotic and non-fibrotic HP are frequently misdiagnosed for other ILDs (sarcoidosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases (SARD)-ILDs, familial pulmonary fibrosis), since the clinical and radiological picture is usually the same. This is caused by the fact that the lung has a limited repertoire of immune reactions to internal and external stimuli, and the only factor that differentiates HP from other ILD is exposure to primarily organic inducers (antigens+admixtures), which is crucial for the initiating and perpetuating of the pathogenetic process in HP. Although proof of exposure is required for a definitive diagnosis of HP in current guidelines, the search for the source of exposure is unsuccessful in up to half of patients with HP.1 Since the treatment of ILD is based not on a precise diagnosis only but also on the biologic behavior of the disease, some may argue that it does not make sense to waste time with an exhaustive search for the inducer, if the treatment of all ILDs is similar. However, the influence of the type of antigen on the clinical picture and the outcome of HP is crucial. For example, HP caused by exposure to metalworking fluids and isocyanates, and the hot tub lung rarely present with fibrotic features. In contrast, cases of HP with indeterminate exposure were more frequently associated with a progressive fibrotic course of the disease. The unfavorable prognosis in the case of indeterminate exposure is probably mainly caused by the fact that patients cannot effectively avoid exposure if it is unknown.2 All these facts support the usefulness of the search for exposure not only from the point of view of correct diagnosis, but also of prognosis and preventive measures.

What kind of tools do we have for the identification of inducing antigens? The basic tool that should be applied to every new patient with ILD is a history of exposure; professional, domestic or related to free-time activities and hobbies.3,4 The bad news is that with this approach we fail in up to 40% of patients with HP to identify the causative antigen despite repeated history taking. Therefore, in the clinical practice of some ILD centers, questionnaires are regularly used, mainly in patients with a radiological picture that is more often compatible with HP and with a higher percentage of lymphocytes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, to increase the probability of identifying the source of exposure.5 However, recent work by Barnes et al. suggests that the exposure identified by the questionnaires may not be clinically relevant.6 But how, then, can we determine which exposure is clinically relevant in a patient with suspected HP and an unknown causative antigen? The use of immunological assays that confirm the immune reaction against potential inducing antigens is suggested. Practically, this usually involves the determination of serum-specific IgG (SsIgGs).7 However, there are several problems with this approach. First, different manufacturers use different cut-off values, usually based on the population tested by the manufacturer. An example is the determination of specific IgG against Aspergillus fumigatus, with different cut-off values for the UK, Japan, or India.8 Sensitivity rates in different populations reflect, among other factors, the geographical or socio-economic characteristics of the populations. Second, exposure to fungi does not always result in the production of SsIgGs. For instance, Vaali et al. examined specific IgG in the serum and stools of individuals with documented occupational exposure to fungi and of nonexposed controls. They found no significant difference in the concentration of SsIgGs against molds cultured from the working space between exposed and unexposed individuals.9 Third, it is not known which antigens from commercially available sets to test. Obviously, the portfolio of potential inducers differs based on geographical and socioeconomic conditions; nevertheless, it seems that the main antigens are common throughout the world. In the meta-analysis of 967 publications performed by Barnes, 62 unique exposures associated with HP were revealed. Interestingly, only three main big groups dominated: birds (32% HP cases), molds (17% HP cases) and antigen-indeterminate (15–24% HP cases).2 Furthermore, in our cohort of 37 HP patients versus 35 controls, we proved most frequently sensitization against molds (A. fumigatus, Candida albicans, and mold mixture) and parrots and mammal hair mixture. Interestingly, we also frequently identified sensitization to mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssimus, Dermatophagoides farinae, Dermatophagoides microceras, and Glycophagus domesticus), which is usually not regularly investigated. This may support the hypothesis that the mites may co-trigger the pathogenetic reaction leading to HP through their immunomodulatory properties.10 In centers with expertise, individual SsIgGs can be performed with the material collected by the patients in their own environment if needed. The results of these individually prepared assays may disclose suspicious inducer in the case when commercially available assays against standard antigens do not reveal the corresponding source of exposure.11

Despite the limitations mentioned above, the use of SsIgGs investigations is reasonable for identifying exposure in newly diagnosed HP, suspected of HP. Usually, the fluorescent enzyme or chemiluminiscence immunoassay method is used. The use of immunoprecipitation on agar (Ouchterlony sec.) is currently used in a minority of laboratories. From the commercially available SsIgG assays, the tests for molds and feathers seem to be most helpful if used in relation with clinical picture of the disease. Since there are significant variations in sensitization and exposure, even within an asymptomatic population, individual laboratories should establish reference ranges within their own populations.12

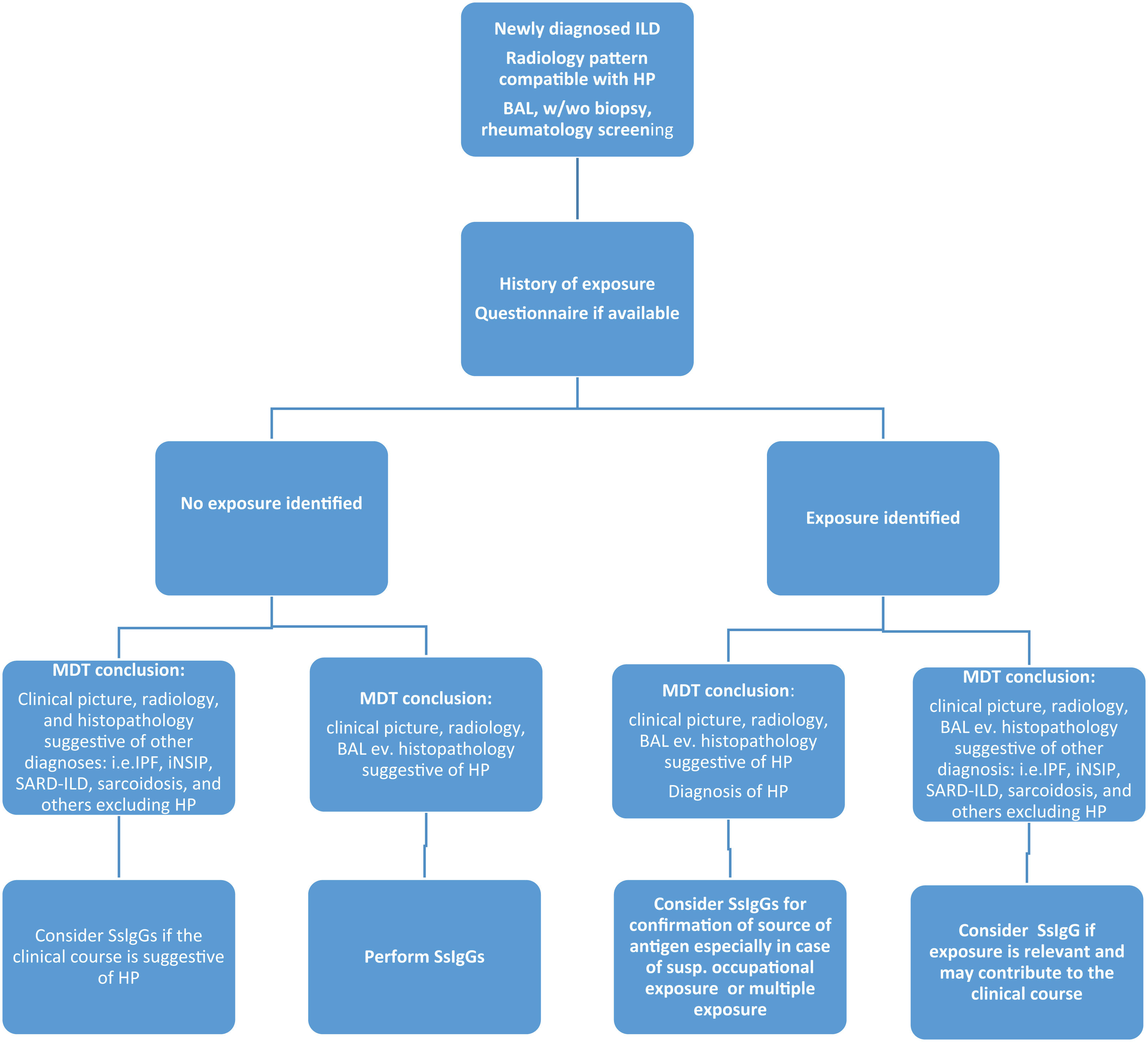

We must always remember that SsIgG values are only part of mosaic in the diagnostic workup of ILDs and should be related to the history and questionnaires and are recommended mainly in these clinical scenarios:

- •

As a part of the diagnostic process in patients with newly revealed ILD, where HP is one of the differentials, that is, when history of exposure is negative, and the multidisciplinary team discussion did not establish another diagnosis.

- •

As a tool for confirmation of the antigen as a sensitizer in the case of multiple sources from history or questionnaires.

- •

As a proof of the causality of exposure and HP in suspicion of occupational disease. In this case, further tests may be demanded (direct challenge or specific inhalation challenge).

- •

Consider performing SsIgGs (ev. individually prepared SsIgS) when the clinical course of ILD raise a suspicion of potential external trigger as a cause of clinical and/or radiologic worsening.

The list of suggestion on the use of SsIgGs in clinical practice is based on data from the literature and our clinical experience (Fig. 1). Clinicians should be aware that SsIgG investigation is a useful tool for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of HP; however, it should be always evaluated in complex with other clinical, radiological, and histopathologic parameters.13 The identification of exposure is crucial not only for diagnosis but also for prognosis, since the patient should be adequately advised to avoid potential sources of exposure.14,15

Suggestion on the use of serum immunoglobulin Gs (SsIgGs) in the clinical practice of newly diagnosed interstitial lung diseases (ILDs). MDT: multidisciplinary team; IPF: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; ILD: Interstitial Lung Disease; iNSIP: idiopathic Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia; SARD-ILD: Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease associated Interstitial Lung Disease; HP: Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; SsIgGs: serum specific immunoglobulin G.

No material in this manuscript has been partially or totally produced with the help of any artificial intelligence software or tool.

Funding of the ResearchThe research mentioned in the Editorial and the work on manuscript itself did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare do not have any conflicts of interest that may be considered to influence directly or indirectly the content of the manuscript.

The authors thank Monika Andělová, Dr. Rer.Nat., Ph.D. for help with language editing of the manuscript.