Polymicrobial pneumonia is a concern for clinicians due to its association with increased disease severity. Determining the prevalence of polymicrobial pneumonia and identifying patients who have an increased risk of this aetiology is important for the management of CAP patients. Here we describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of adult hospitalized patients with CAP, and identify the risk factors related to polymicrobial pneumonia and specifically to 30-day mortality.

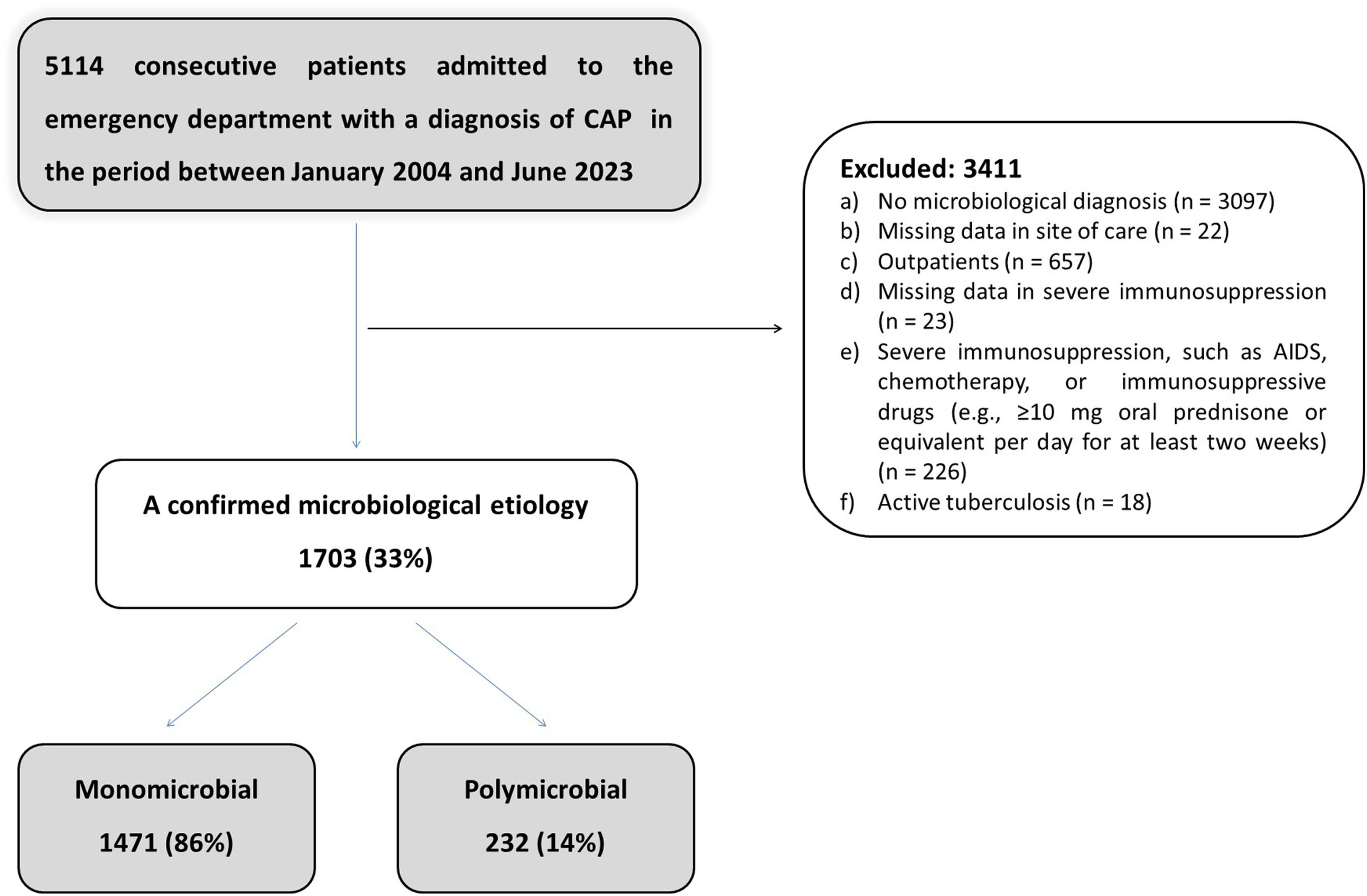

MethodsReal-life retrospective study from a prospectively collected data including 5114 consecutive adult patients hospitalized with CAP; 1703 patients had an established aetiology.

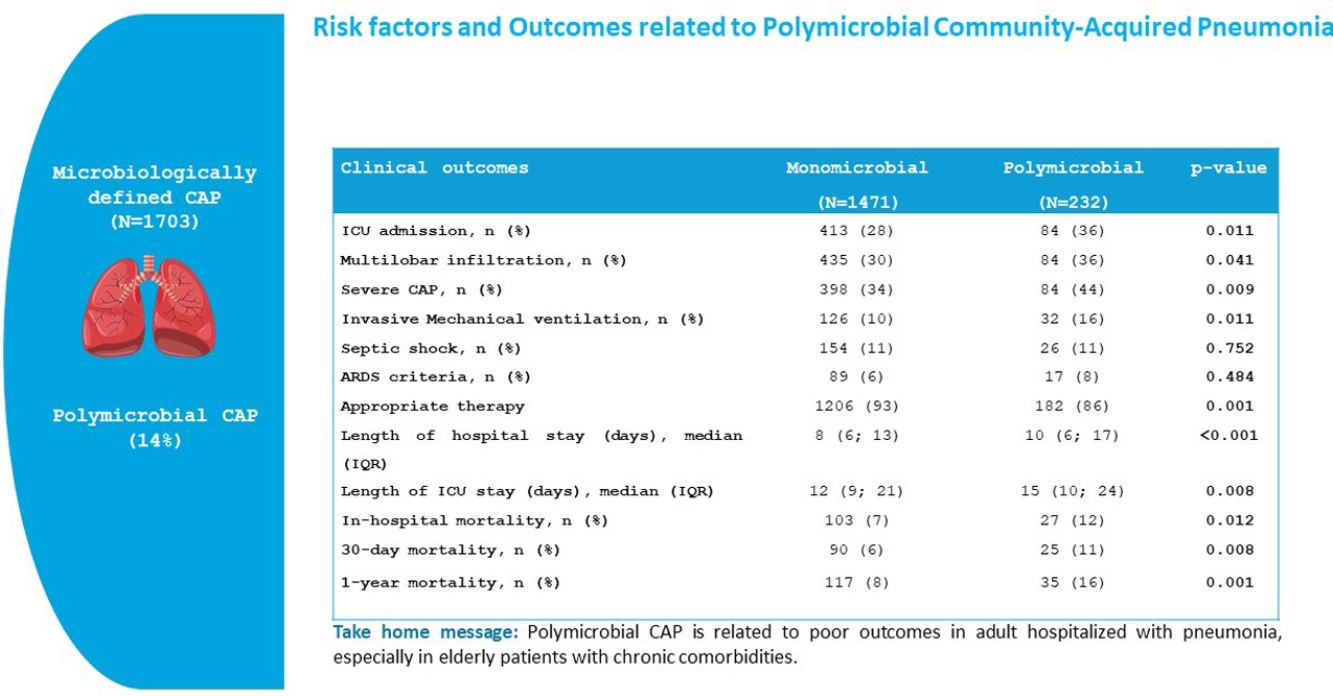

ResultsPolymicrobial infection was present in 14% of the CAP patients with defined microbial aetiology (64% of ward patients and 28% of ICU patients). The most frequent polymicrobial infections were: Streptococcus pneumoniae+respiratory virus (32%), S. pneumoniae+Haemophilus influenzae (7%) and S. pneumoniae+Staphylococcus aureus (7%). Inappropriate initial antimicrobial treatment was more frequent in the polymicrobial aetiology group than in the monomicrobial aetiology group (14% vs. 7%, p=0.001). In-hospital (12% vs. 7%, p=0.012), 30-day (11% vs. 6%, p=0.008) and 1-year mortality (16% vs. 8%, p=0.001) were higher in the polymicrobial group. Multilobar pneumonia (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.00–1.80) was an independent risk factor for polymicrobial aetiology in the multivariable analysis, while fever (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.43–0.80) was independently associated with a lower risk for this condition. Polymicrobial infection was an independent predictor of 30-day mortality in the multivariable analysis (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.17–2.87; p=0.008).

ConclusionsPolymicrobial infection was related to poor outcomes in adults hospitalized with CAP, especially in elderly patients with chronic comorbidities. Polymicrobial infection was a risk factor for 30-day mortality.

Establishing the microbial aetiology of pneumonia is crucial in order to provide more targeted therapy, to prevent the overuse of antibiotics (especially broad spectrum antimicrobials) and to avoid complications related to antibiotic use.1 However, despite the implementation of molecular tests and the advances in the diagnosis of pneumonia in the last two decades, the aetiology is identified in only approximately 50% of cases.2,3

In a previous study we found that polymicrobial pneumonia was present in 11% of ICU patients with CAP, and identified it as a risk factor for inappropriate antimicrobial treatment, which is known to increase mortality in these patients.4 We also observed a trend towards higher in-hospital mortality of patients with polymicrobial CAP than in patients with the monomicrobial form. However, the low number of patients in that study meant that it was difficult to present firm conclusions. Recent studies have reported an adverse impact on the severity of the pneumonia and increased readmission and mortality rates in patients with CAP caused by co-infections.5–7 However, little is known about outcomes of polymicrobial pneumonia with regard to the site of care and the microorganism group. The main objective of this study was to investigate the risk factors and outcomes related to polymicrobial aetiology in adult hospitalized patients with CAP.

Material and MethodsEthics StatementThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution. The requirement of written informed consent was waived due to the non-interventional design.

Study PopulationThis is a retrospective observational cohort study of all consecutive adult patients with CAP admitted to the Intensive Emergency Department of an 850-bed tertiary care university hospital between January 2004 and June 2023. Pneumonia was defined as a new pulmonary infiltrate found on the hospital admission chest radiograph and symptoms and signs of lower respiratory tract infection. We excluded patients with immunosuppression (e.g., patients with neutropenia after chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation), hospital admission for ≥48h in the preceding 14 days, patients with drug-induced immunosuppression as a result of solid-organ transplantation or corticosteroid (>10mg/day) or cytotoxic therapy, patients with chronic bronchial infection (defined as at least two respiratory isolates of the same pathogen in the last year before pneumonia), all HIV-infected patients and patients who were SARS-CoV-2 positive at admission.

Data Collection and EvaluationThe following parameters were recorded at admission: age, sex, tobacco use, alcohol and drug consumption, co-morbidities (chronic respiratory disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and bronchiectasis among others, diabetes mellitus, chronic cardiovascular disease, neurological disease, chronic renal disease, chronic liver disease), antibiotic treatment in the 30 days before hospital admission, treatment with corticosteroids, clinical symptoms and features (fever, cough, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea, mental confusion, and aspiration), clinical signs (blood pressure, body temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate), arterial blood gas measurements, chest radiograph findings (number of lobes affected, pleural effusion, and atelectasis), laboratory parameters (haemoglobin level, WBC count, platelet count, serum creatinine level, C-reactive protein level, and other biochemical parameters), diagnostic procedures, empiric antibiotic therapy, ventilatory support, pulmonary complications (empyema, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) criteria, pleural effusion, surgical pleural draining), other clinical events (cardiac arrhythmias, septic shock, acute renal failure). The duration of treatment, length of hospital stay, and 30-day in-hospital mortality were noted. We also calculated the PSI[8] at admission.

Microbiological Evaluation and Diagnostic CriteriaThe required microbiological tests were performed in accordance with standard medical protocols and according to the criteria set by the attending physician. Microbiological examination was performed in sputum, urine, two samples of blood and nasopharyngeal swabs. Pleural puncture, tracheobronchial aspirates (TBAS) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were collected when available. Conventional tests were used to evaluate the presence of bacterial, parasitic and fungal agents, and respiratory viruses. Sputum and pleural fluid samples were qualitatively cultured for bacterial pathogens, fungi and mycobacteria. BAS and BAL samples were homogenized and processed for quantitative culture by serial dilutions for bacterial pathogens; undiluted cultures for Legionella spp., fungi and mycobacteria were also carried out.

Nasopharyngeal swabs and BAL specimens were processed for antigen detection by immune fluorescence assay (IFA) and for isolation of viruses in cell culture (influenza virus A, influenza virus B, human parainfluenza virus 1–3, adenovirus and respiratory syncytial virus). In addition, two independent multiplex-nested RT-PCR assays able to detect from 1 to 10copies of viral genomes were performed for the diagnosis of respiratory viruses. One RT-PCR assay detected influenza virus types A, B and C, respiratory syncytial virus A and B, and adenovirus. Another RT-PCR assay studied parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, 3 and 4, coronaviruses 229E and OC43, rhinoviruses and enteroviruses.8 All positive viral results were subsequently confirmed by a second independent assay.

Sputum and blood samples were obtained for bacterial culture before the start of antibiotic therapy in the emergency department. Nasopharyngeal swabs for detecting respiratory virus detection and urine samples for detecting Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila antigen were obtained in the emergency department and within 24h of hospital admission. BAL and BAS samples were obtained within 48h of admission.

Criteria for Etiological DiagnosisThe aetiology was considered definite if one of the following criteria was met: (1) a positive blood culture (in the absence of an apparent extra-pulmonary focus); (2) a positive bacterial culture of pleural fluid or transthoracic needle aspiration samples; (3) elevated serum levels of IgM against Chlamydophila pneumoniae (≥1:64), Coxiella burnetii (≥1:80) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (any positive titre); (4) seroconversion (i.e., a fourfold increase in IgG titres) for C. pneumoniae and L. pneumophila>1:128, C. burnetii>1:80 and respiratory viruses (influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza viruses 1–3, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus); (5) positive urinary antigen for L. pneumophila (Binax Now L. pneumophila urinary Antigen Test; Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland); (6) positive urinary antigen for S. pneumoniae (Binax Now Streptococcus pneumoniae urinary Antigen Test; Emergo Europe, The Hague, The Netherlands); (7) bacterial growth in cultures of TBAS (≥105cfu/ml), in protected specimen brush (≥103cfu/ml), and BAL (≥104cfu/ml); (8) detection of antigens by IFA plus virus isolation or detection by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing for respiratory virus (influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza virus 1–3, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus).

The aetiology of pneumonia was classified as presumptive when a predominant microorganism was isolated from a purulent sample (leukocytes>25 per high power microscopic field and few epithelial cells<10 per high power microscopic field) and the findings of Gram staining were compatible. For the purpose of this study, presumptive and definitive diagnoses were analyzed together.

DefinitionsPolymicrobial pneumonia was defined as pneumonia due to more than one pathogen. Severe CAP was defined when at least one major or three minor criteria of the Infectious Disease Society of America/American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) guidelines were met.9 Empiric antibiotic treatment was defined as appropriate when the isolated pathogens were susceptible in vitro to one of the antimicrobials administered according to current European guidelines for microbiological susceptibility testing (http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/). For Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, adequate treatment needed a combination of two active antibiotics against the isolated strain.

Statistical AnalysisCategorical variables were described by frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables by means and standard deviations (SD), or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for non-normally distributed data (using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Categorical variables were compared with the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test where appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the Student's t-test once normality was demonstrated; otherwise, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was performed.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses9 were performed to identify predictors of patients with polymicrobial pneumonia (dependent variables). Factors showing an association in the univariate analyses (p<0.25) were incorporated into the multivariable logistic regression model. Final variable selection was performed using the backward stepwise selection method (likelihood ratio) (pin<0.05, pout>0.10). Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was performed to assess the overall fit of the regression model. Univariate and multivariable Cox regression analyses10 were also performed to predict 30-day mortality (dependent variable), with similar inclusion criteria applied for the Cox regression analysis (p<0.25). Patients who were lost to follow-up were censored in survival analyses. Hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Assessment of discrimination in the multivariable Cox model was measured using Harrell's C and Somers’ D. The interaction between monomicrobial/polymicrobial and ward/ICU admission and between monomicrobial/polymicrobial and empiric antimicrobial therapy were analyzed but not included in the final Cox regression model because of the lack of significance.

Single collinearity in multivariable analyses was evaluated using the Pearson correlation (r) and multicollinearity was examined by means of the variance inflation factor (VIF).

To account for missing data we used the multiple imputation method.10,11

All tests were two-tailed and significance was set at 5%. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 26.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsDuring the study period, a total of 5114 patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) were admitted to the emergency department. Of these, 916 were excluded for the following reasons: 657 were outpatients, 226 had severe immunosuppression, 45 had missing data, and 18 had active tuberculosis. Therefore, the final study population comprised 4198 patients, of whom 1703 had a microbiological diagnosis and 2495 did not (Fig. 1). Patients included in the study were prospectively evaluated and followed up. Among the 1703 hospitalized patients with CAP with confirmed aetiology, monomicrobial aetiology was identified in 1471 (86%) – 413 ICU patients (83%) and 1058 ward patients (88%) – and polymicrobial diagnoses in 232 (14%) – 84 ICU patients (17%) and 148 ward patients (12%). We compared the outcomes between pneumonias without defined aetiology (2495; 59%) and cases of monomicrobial (1471; 35%) and polymicrobial aetiology (232; 6%). In general, polymicrobial cases had significantly higher rates of ICU admission and in-hospital and 30-day mortality than monomicrobial cases and pneumonias without defined aetiology. Monomicrobial cases had a higher 1-year mortality rate than pneumonia without aetiology, while the 1-year mortality rate of polymicrobial cases was higher than in monomicrobial cases (Supplementary Table 1).

Altogether, 1703 (41%) of the hospitalized CAP patients had a confirmed microbiological aetiology (≥3 microbiological tests performed in 1491 cases, and <3 microbiological tests performed in 212 cases) among whom 1471 patients (86%) presented monomicrobial aetiology (72% admitted to the ward and 28% admitted to the ICU), and 232 patients (14%) had polymicrobial aetiology (64% admitted to the ward and 36% admitted to the ICU) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The specimens obtained included blood cultures from 1360 patients (79%), urinary antigens from 1381 (81%), nasopharyngeal swab from 916 (54%) sputum sample from 890 (52%), acute and convalescent serum sample for serology from 262 (15%), bronchoscopically obtained lower respiratory secretions from 253 (15%), and pleural fluid from 183 (11%). The positive percentages for each test were as follows: blood culture, 12%; pleural fluid culture, 22.3%; bronchial aspirate sample, 53.1%; urinary antigen for S. pneumoniae, 17.1%; urinary antigen for Legionella, 3%; sputum culture, 50%; nasopharyngeal swab, 24%; and serology, 66%.

Median age was 67 years (range 55–81) and most patients were male (61%).

Among 1703 patients with confirmed aetiology, 572 (34%) were treated with β-lactam+macrolide (493 monomicrobial, 79 polymicrobial); 503 (30%) received β-lactam+fluroquinolones (438 monomicrobial, 65 polymicrobial), 298 (17%) received monotherapy with fluoroquinolones (264 monomicrobial, 34 polymicrobial), 106 (6%) received β-lactam monotherapy (90 monomicrobial, 16 polymicrobial) and 177 (10%) received other combinations (144 monomicrobial, 33 polymicrobial).

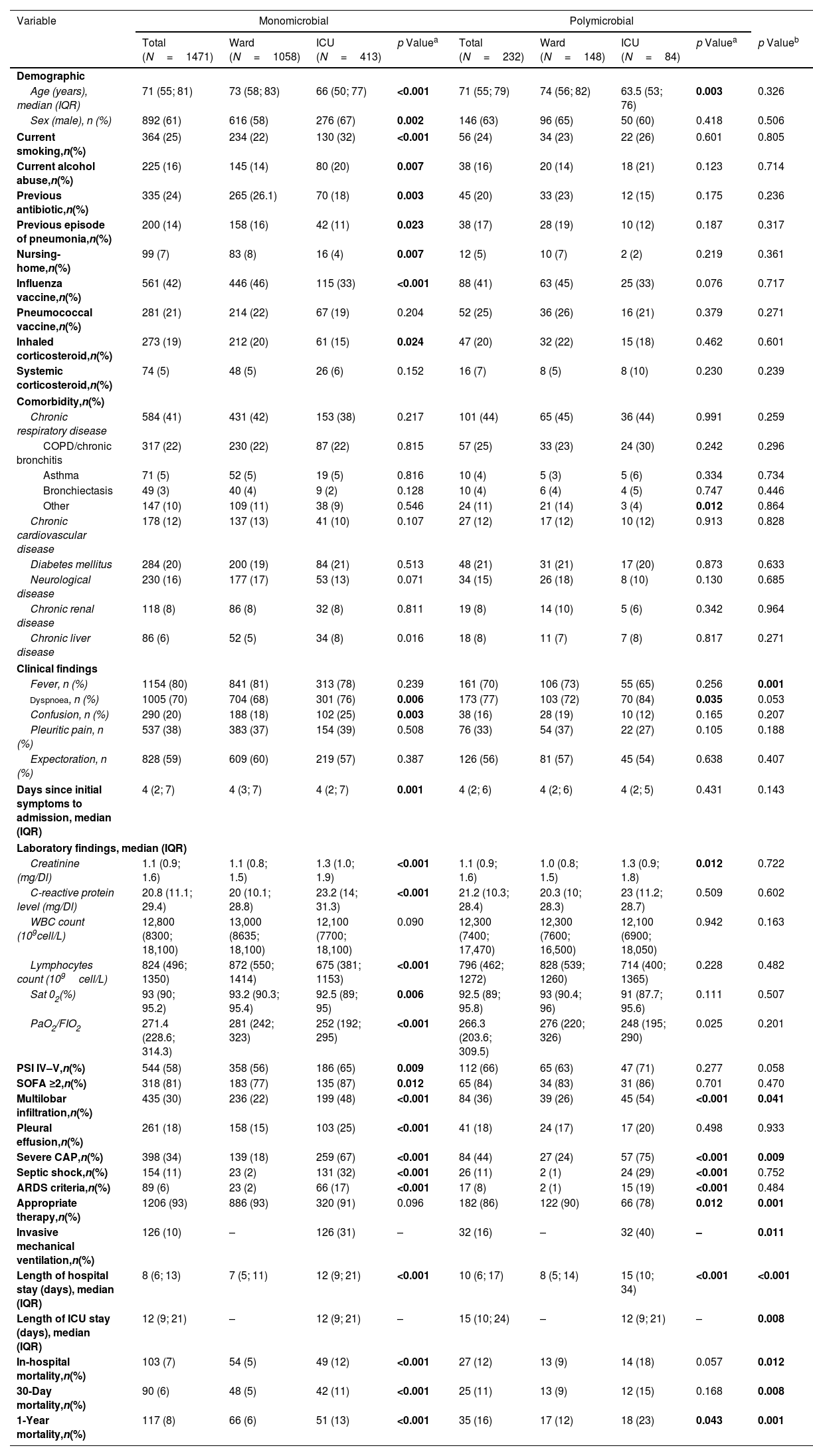

Aetiology by Site of CareA total of 1471 patients (86%) presented monomicrobial aetiology, of whom 72% were admitted to the ward and 28% to the ICU. Two hundred and thirty-two patients (14%) had a polymicrobial aetiology, of whom 64% were admitted to the ward and 36% to the ICU. The main clinical characteristics and outcomes are displayed in Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population According to Aetiology and Site of Care.

| Variable | Monomicrobial | Polymicrobial | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=1471) | Ward (N=1058) | ICU (N=413) | p Valuea | Total (N=232) | Ward (N=148) | ICU (N=84) | p Valuea | p Valueb | |

| Demographic | |||||||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 71 (55; 81) | 73 (58; 83) | 66 (50; 77) | <0.001 | 71 (55; 79) | 74 (56; 82) | 63.5 (53; 76) | 0.003 | 0.326 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 892 (61) | 616 (58) | 276 (67) | 0.002 | 146 (63) | 96 (65) | 50 (60) | 0.418 | 0.506 |

| Current smoking,n(%) | 364 (25) | 234 (22) | 130 (32) | <0.001 | 56 (24) | 34 (23) | 22 (26) | 0.601 | 0.805 |

| Current alcohol abuse,n(%) | 225 (16) | 145 (14) | 80 (20) | 0.007 | 38 (16) | 20 (14) | 18 (21) | 0.123 | 0.714 |

| Previous antibiotic,n(%) | 335 (24) | 265 (26.1) | 70 (18) | 0.003 | 45 (20) | 33 (23) | 12 (15) | 0.175 | 0.236 |

| Previous episode of pneumonia,n(%) | 200 (14) | 158 (16) | 42 (11) | 0.023 | 38 (17) | 28 (19) | 10 (12) | 0.187 | 0.317 |

| Nursing-home,n(%) | 99 (7) | 83 (8) | 16 (4) | 0.007 | 12 (5) | 10 (7) | 2 (2) | 0.219 | 0.361 |

| Influenza vaccine,n(%) | 561 (42) | 446 (46) | 115 (33) | <0.001 | 88 (41) | 63 (45) | 25 (33) | 0.076 | 0.717 |

| Pneumococcal vaccine,n(%) | 281 (21) | 214 (22) | 67 (19) | 0.204 | 52 (25) | 36 (26) | 16 (21) | 0.379 | 0.271 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid,n(%) | 273 (19) | 212 (20) | 61 (15) | 0.024 | 47 (20) | 32 (22) | 15 (18) | 0.462 | 0.601 |

| Systemic corticosteroid,n(%) | 74 (5) | 48 (5) | 26 (6) | 0.152 | 16 (7) | 8 (5) | 8 (10) | 0.230 | 0.239 |

| Comorbidity,n(%) | |||||||||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 584 (41) | 431 (42) | 153 (38) | 0.217 | 101 (44) | 65 (45) | 36 (44) | 0.991 | 0.259 |

| COPD/chronic bronchitis | 317 (22) | 230 (22) | 87 (22) | 0.815 | 57 (25) | 33 (23) | 24 (30) | 0.242 | 0.296 |

| Asthma | 71 (5) | 52 (5) | 19 (5) | 0.816 | 10 (4) | 5 (3) | 5 (6) | 0.334 | 0.734 |

| Bronchiectasis | 49 (3) | 40 (4) | 9 (2) | 0.128 | 10 (4) | 6 (4) | 4 (5) | 0.747 | 0.446 |

| Other | 147 (10) | 109 (11) | 38 (9) | 0.546 | 24 (11) | 21 (14) | 3 (4) | 0.012 | 0.864 |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 178 (12) | 137 (13) | 41 (10) | 0.107 | 27 (12) | 17 (12) | 10 (12) | 0.913 | 0.828 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 284 (20) | 200 (19) | 84 (21) | 0.513 | 48 (21) | 31 (21) | 17 (20) | 0.873 | 0.633 |

| Neurological disease | 230 (16) | 177 (17) | 53 (13) | 0.071 | 34 (15) | 26 (18) | 8 (10) | 0.130 | 0.685 |

| Chronic renal disease | 118 (8) | 86 (8) | 32 (8) | 0.811 | 19 (8) | 14 (10) | 5 (6) | 0.342 | 0.964 |

| Chronic liver disease | 86 (6) | 52 (5) | 34 (8) | 0.016 | 18 (8) | 11 (7) | 7 (8) | 0.817 | 0.271 |

| Clinical findings | |||||||||

| Fever, n (%) | 1154 (80) | 841 (81) | 313 (78) | 0.239 | 161 (70) | 106 (73) | 55 (65) | 0.256 | 0.001 |

| Dyspnoea, n (%) | 1005 (70) | 704 (68) | 301 (76) | 0.006 | 173 (77) | 103 (72) | 70 (84) | 0.035 | 0.053 |

| Confusion, n (%) | 290 (20) | 188 (18) | 102 (25) | 0.003 | 38 (16) | 28 (19) | 10 (12) | 0.165 | 0.207 |

| Pleuritic pain, n (%) | 537 (38) | 383 (37) | 154 (39) | 0.508 | 76 (33) | 54 (37) | 22 (27) | 0.105 | 0.188 |

| Expectoration, n (%) | 828 (59) | 609 (60) | 219 (57) | 0.387 | 126 (56) | 81 (57) | 45 (54) | 0.638 | 0.407 |

| Days since initial symptoms to admission, median (IQR) | 4 (2; 7) | 4 (3; 7) | 4 (2; 7) | 0.001 | 4 (2; 6) | 4 (2; 6) | 4 (2; 5) | 0.431 | 0.143 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | |||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/Dl) | 1.1 (0.9; 1.6) | 1.1 (0.8; 1.5) | 1.3 (1.0; 1.9) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.9; 1.6) | 1.0 (0.8; 1.5) | 1.3 (0.9; 1.8) | 0.012 | 0.722 |

| C-reactive protein level (mg/Dl) | 20.8 (11.1; 29.4) | 20 (10.1; 28.8) | 23.2 (14; 31.3) | <0.001 | 21.2 (10.3; 28.4) | 20.3 (10; 28.3) | 23 (11.2; 28.7) | 0.509 | 0.602 |

| WBC count (109cell/L) | 12,800 (8300; 18,100) | 13,000 (8635; 18,100) | 12,100 (7700; 18,100) | 0.090 | 12,300 (7400; 17,470) | 12,300 (7600; 16,500) | 12,100 (6900; 18,050) | 0.942 | 0.163 |

| Lymphocytes count (109cell/L) | 824 (496; 1350) | 872 (550; 1414) | 675 (381; 1153) | <0.001 | 796 (462; 1272) | 828 (539; 1260) | 714 (400; 1365) | 0.228 | 0.482 |

| Sat 02(%) | 93 (90; 95.2) | 93.2 (90.3; 95.4) | 92.5 (89; 95) | 0.006 | 92.5 (89; 95.8) | 93 (90.4; 96) | 91 (87.7; 95.6) | 0.111 | 0.507 |

| PaO2/FIO2 | 271.4 (228.6; 314.3) | 281 (242; 323) | 252 (192; 295) | <0.001 | 266.3 (203.6; 309.5) | 276 (220; 326) | 248 (195; 290) | 0.025 | 0.201 |

| PSI IV–V,n(%) | 544 (58) | 358 (56) | 186 (65) | 0.009 | 112 (66) | 65 (63) | 47 (71) | 0.277 | 0.058 |

| SOFA ≥2,n(%) | 318 (81) | 183 (77) | 135 (87) | 0.012 | 65 (84) | 34 (83) | 31 (86) | 0.701 | 0.470 |

| Multilobar infiltration,n(%) | 435 (30) | 236 (22) | 199 (48) | <0.001 | 84 (36) | 39 (26) | 45 (54) | <0.001 | 0.041 |

| Pleural effusion,n(%) | 261 (18) | 158 (15) | 103 (25) | <0.001 | 41 (18) | 24 (17) | 17 (20) | 0.498 | 0.933 |

| Severe CAP,n(%) | 398 (34) | 139 (18) | 259 (67) | <0.001 | 84 (44) | 27 (24) | 57 (75) | <0.001 | 0.009 |

| Septic shock,n(%) | 154 (11) | 23 (2) | 131 (32) | <0.001 | 26 (11) | 2 (1) | 24 (29) | <0.001 | 0.752 |

| ARDS criteria,n(%) | 89 (6) | 23 (2) | 66 (17) | <0.001 | 17 (8) | 2 (1) | 15 (19) | <0.001 | 0.484 |

| Appropriate therapy,n(%) | 1206 (93) | 886 (93) | 320 (91) | 0.096 | 182 (86) | 122 (90) | 66 (78) | 0.012 | 0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation,n(%) | 126 (10) | – | 126 (31) | – | 32 (16) | – | 32 (40) | – | 0.011 |

| Length of hospital stay (days), median (IQR) | 8 (6; 13) | 7 (5; 11) | 12 (9; 21) | <0.001 | 10 (6; 17) | 8 (5; 14) | 15 (10; 34) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Length of ICU stay (days), median (IQR) | 12 (9; 21) | – | 12 (9; 21) | – | 15 (10; 24) | – | 12 (9; 21) | – | 0.008 |

| In-hospital mortality,n(%) | 103 (7) | 54 (5) | 49 (12) | <0.001 | 27 (12) | 13 (9) | 14 (18) | 0.057 | 0.012 |

| 30-Day mortality,n(%) | 90 (6) | 48 (5) | 42 (11) | <0.001 | 25 (11) | 13 (9) | 12 (15) | 0.168 | 0.008 |

| 1-Year mortality,n(%) | 117 (8) | 66 (6) | 51 (13) | <0.001 | 35 (16) | 17 (12) | 18 (23) | 0.043 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: ARDS indicates acute respiratory distress syndrome; CAP, community acquired pneumonia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; PSI, pneumonia severity index; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; WBC, white blood count.

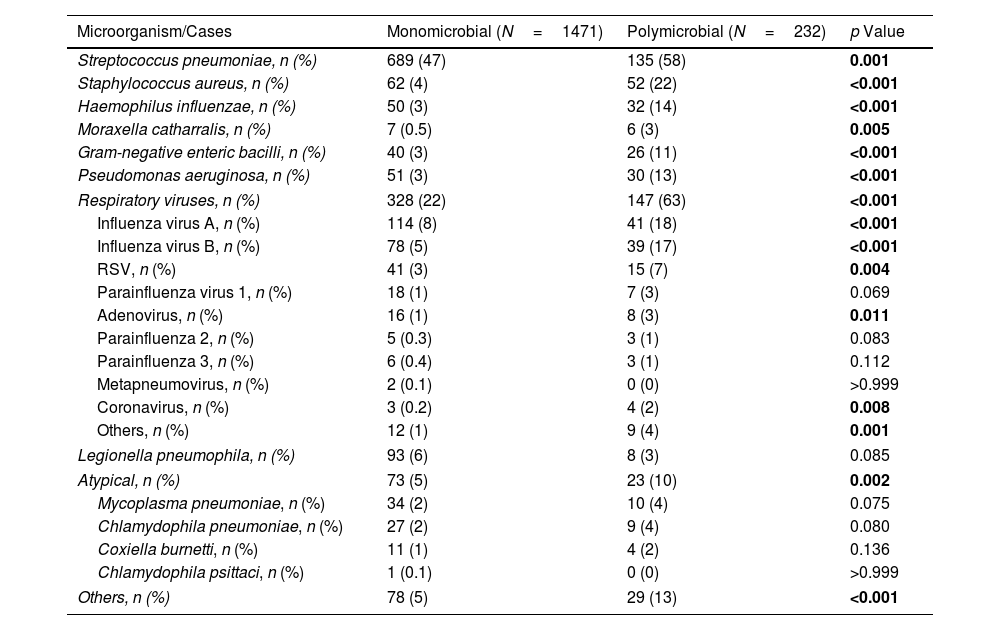

In the monomicrobial group, patients admitted to the ICU were younger, more likely to be male, smokers, and consumers of alcohol, and more frequently presented dyspnoea and confusion; they presented higher rates of sepsis and pulmonary and extra-pulmonary complications and higher rates of intra, 30-day and 1-year mortality than patients admitted to the wards. In the monomicrobial pneumonia group, S. pneumoniae was the most frequent microorganism (47%), followed by respiratory viruses (22%) and Legionella pneumophila (6%) (Table 2).

Distribution of the Causative Microorganisms Identified in 1703 Patients With CAP.

| Microorganism/Cases | Monomicrobial (N=1471) | Polymicrobial (N=232) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae, n (%) | 689 (47) | 135 (58) | 0.001 |

| Staphylococcus aureus, n (%) | 62 (4) | 52 (22) | <0.001 |

| Haemophilus influenzae, n (%) | 50 (3) | 32 (14) | <0.001 |

| Moraxella catharralis, n (%) | 7 (0.5) | 6 (3) | 0.005 |

| Gram-negative enteric bacilli, n (%) | 40 (3) | 26 (11) | <0.001 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa, n (%) | 51 (3) | 30 (13) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory viruses, n (%) | 328 (22) | 147 (63) | <0.001 |

| Influenza virus A, n (%) | 114 (8) | 41 (18) | <0.001 |

| Influenza virus B, n (%) | 78 (5) | 39 (17) | <0.001 |

| RSV, n (%) | 41 (3) | 15 (7) | 0.004 |

| Parainfluenza virus 1, n (%) | 18 (1) | 7 (3) | 0.069 |

| Adenovirus, n (%) | 16 (1) | 8 (3) | 0.011 |

| Parainfluenza 2, n (%) | 5 (0.3) | 3 (1) | 0.083 |

| Parainfluenza 3, n (%) | 6 (0.4) | 3 (1) | 0.112 |

| Metapneumovirus, n (%) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| Coronavirus, n (%) | 3 (0.2) | 4 (2) | 0.008 |

| Others, n (%) | 12 (1) | 9 (4) | 0.001 |

| Legionella pneumophila, n (%) | 93 (6) | 8 (3) | 0.085 |

| Atypical, n (%) | 73 (5) | 23 (10) | 0.002 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae, n (%) | 34 (2) | 10 (4) | 0.075 |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae, n (%) | 27 (2) | 9 (4) | 0.080 |

| Coxiella burnetti, n (%) | 11 (1) | 4 (2) | 0.136 |

| Chlamydophila psittaci, n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| Others, n (%) | 78 (5) | 29 (13) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

In the polymicrobial group, patients admitted to the ICU were younger, had higher rates of dyspnoea, multilobar infiltration, severe CAP, septic shock and ARDS; they also had higher rates of in-hospital, 30-day and one-year mortality than ward patients (Table 1).

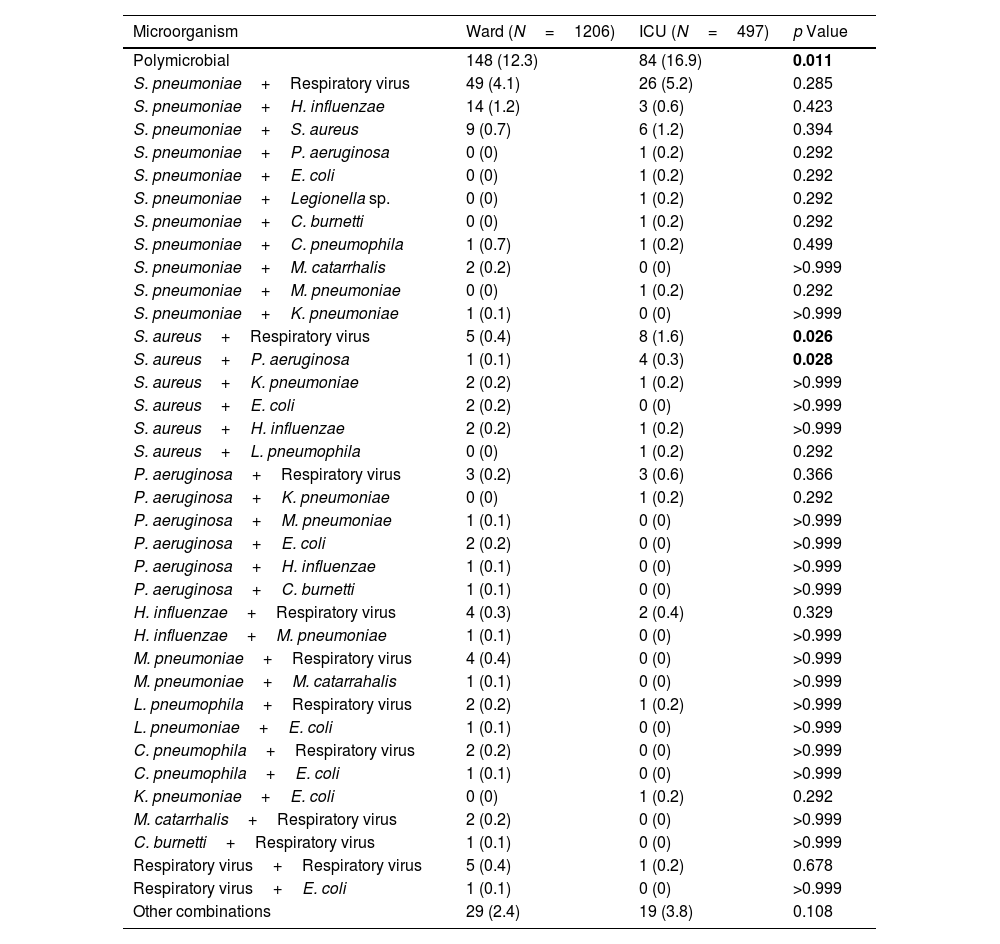

The most frequent combinations of pathogens were S. pneumoniae+respiratory virus (32%), S. pneumoniae+H.influenzae (7%), S. pneumoniae+Staphylococcus aureus (7%), respiratory viruses+S. aureus (6%). Forty-eight patients (21%) have a polymicrobial aetiology, which includes three microorganisms. The most frequent combination was S. pneumoniae, Gram-negative enteric bacilli, and respiratory viruses. The combinations of S. aureus plus respiratory viruses and S. aureus plus P. aeruginosa were significantly more frequent in the ICU compared to the ward (Tables 2 and 3).

Polymicrobial Etiologies.

| Microorganism | Ward (N=1206) | ICU (N=497) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymicrobial | 148 (12.3) | 84 (16.9) | 0.011 |

| S. pneumoniae+Respiratory virus | 49 (4.1) | 26 (5.2) | 0.285 |

| S. pneumoniae+H. influenzae | 14 (1.2) | 3 (0.6) | 0.423 |

| S. pneumoniae+S. aureus | 9 (0.7) | 6 (1.2) | 0.394 |

| S. pneumoniae+P. aeruginosa | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.292 |

| S. pneumoniae+E. coli | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.292 |

| S. pneumoniae+Legionella sp. | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.292 |

| S. pneumoniae+C. burnetti | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.292 |

| S. pneumoniae+C. pneumophila | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0.499 |

| S. pneumoniae+M. catarrhalis | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| S. pneumoniae+M. pneumoniae | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.292 |

| S. pneumoniae+K. pneumoniae | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| S. aureus+Respiratory virus | 5 (0.4) | 8 (1.6) | 0.026 |

| S. aureus+P. aeruginosa | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 0.028 |

| S. aureus+K. pneumoniae | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | >0.999 |

| S. aureus+E. coli | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| S. aureus+H. influenzae | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | >0.999 |

| S. aureus+L. pneumophila | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.292 |

| P. aeruginosa+Respiratory virus | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.6) | 0.366 |

| P. aeruginosa+K. pneumoniae | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.292 |

| P. aeruginosa+M. pneumoniae | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| P. aeruginosa+E. coli | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| P. aeruginosa+H. influenzae | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| P. aeruginosa+C. burnetti | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| H. influenzae+Respiratory virus | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 0.329 |

| H. influenzae+M. pneumoniae | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| M. pneumoniae+Respiratory virus | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| M. pneumoniae+M. catarrahalis | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| L. pneumophila+Respiratory virus | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | >0.999 |

| L. pneumoniae+E. coli | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| C. pneumophila+Respiratory virus | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| C. pneumophila+E. coli | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| K. pneumoniae+E. coli | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.292 |

| M. catarrhalis+Respiratory virus | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| C. burnetti+Respiratory virus | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| Respiratory virus+Respiratory virus | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0.678 |

| Respiratory virus+E. coli | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| Other combinations | 29 (2.4) | 19 (3.8) | 0.108 |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit. Other combinations include cases with 3 microorganisms, with the most frequent combination being S. pneumoniae, Gram-negative enteric bacilli, and respiratory viruses.

The main characteristics of patients and the outcome variables according to aetiology are shown in Table 1.

Baseline CharacteristicsNo differences were found with regard to age, sex, toxic habits, previous antibiotic treatment, severity according to PSI score, or proportions of chronic comorbidities.

Clinical PresentationFever was more frequently observed in patients with monomicrobial pneumonia (80% vs. 70%, p<0.001), while patients with polymicrobial CAP presented higher rates of multilobar involvement (30% vs. 36%, p=0.041). There were no differences with regard to other radiographic or laboratory findings between groups (Table 1).

Severity and OutcomePatients with polymicrobial pneumonia presented higher rates of severe CAP (34% vs. 44%, p=0.009), ICU admission (28% vs. 36%, p=0.011), and invasive mechanical ventilation (10% vs. 16%, p=0.011), and longer hospital stay (8 days vs. 10 days, p<0.001), and ICU stay (12 days vs. 15 days, p=0.008) than the monomicrobial group. The rate of appropriate antimicrobial therapy was higher in patients with monomicrobial aetiology (93% vs. 86%, p<0.001).

In-hospital, 30-day and 1 year-mortality were 8%, 7% and 9% respectively. The polymicrobial group presented higher rates of in-hospital (7% vs. 12%, p=0.012), 30-day (6% vs. 11%, p=0.008) and 1-year mortality (8% vs. 16%, p<0.001) than the monomicrobial aetiology group.

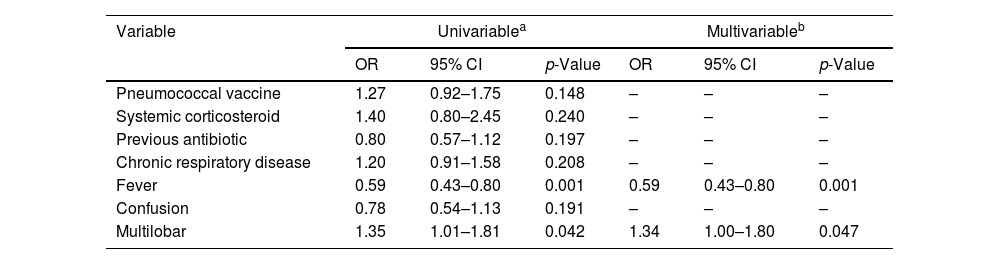

Predictors of Polymicrobial AetiologyAmong the different variables associated with polymicrobial in the univariate analysis (Table 4), multilobar involvement was independently associated with polymicrobial aetiology in the multivariable analysis, while fever was independently associated to a lower risk for this condition.

Significant Univariable Logistic Regression Analyses for Variables Associated With Polymicrobial and Independent Predictors of Polymicrobyal Determined by Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis (N=1703).

| Variable | Univariablea | Multivariableb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Pneumococcal vaccine | 1.27 | 0.92–1.75 | 0.148 | – | – | – |

| Systemic corticosteroid | 1.40 | 0.80–2.45 | 0.240 | – | – | – |

| Previous antibiotic | 0.80 | 0.57–1.12 | 0.197 | – | – | – |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 1.20 | 0.91–1.58 | 0.208 | – | – | – |

| Fever | 0.59 | 0.43–0.80 | 0.001 | 0.59 | 0.43–0.80 | 0.001 |

| Confusion | 0.78 | 0.54–1.13 | 0.191 | – | – | – |

| Multilobar | 1.35 | 1.01–1.81 | 0.042 | 1.34 | 1.00–1.80 | 0.047 |

Abbreviations: CI indicates confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio. Data are shown as estimated ORs (95% CIs) of the explanatory variables in the polymicrobial group. The OR represents the odds that the presence of polymicrobial will occur given exposure of the explanatory variable, compared to the odds of the outcome occurring in the absence of that exposure. The p-value is based on the null hypothesis that all ORs relating to an explanatory variable equal unity (no effect).

The variables analyzed in the univariable analyses were age, sex, smoking habit, alcohol habit, pneumococcal vaccine, influenza vaccine, systemic corticosteroid, inhaled corticosteroid, previous antibiotic, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic cardiovascular disease, chronic renal disease, chronic liver disease, diabetes mellitus, neurological disease, fever, confusion, creatinine, C-reactive protein, lymphocytes count, multilobar infiltration, ARDS, and septic shock.

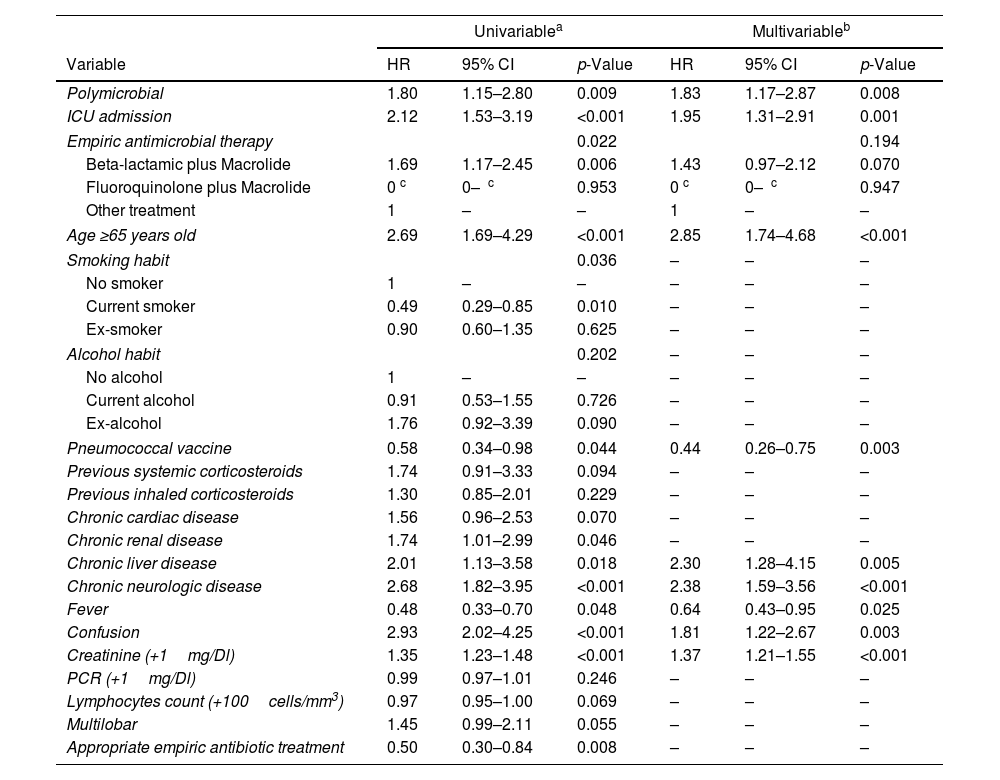

In the multivariable analysis (Table 5), age≥65 years old, chronic liver disease, chronic neurologic disease, confusion, higher creatinine levels, ICU admission and polymicrobial aetiology were independently associated with increased 30-day mortality. In contrast, pneumococcal vaccine and fever were independently associated with decreased 30-day mortality.

Univariate Cox Regression Analysis for Variables Associated With 30-Day Mortality and Independent Predictors of 30-Day Mortality Determined by Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis (N=1703).

| Univariablea | Multivariableb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | HR | 95% CI | p-Value |

| Polymicrobial | 1.80 | 1.15–2.80 | 0.009 | 1.83 | 1.17–2.87 | 0.008 |

| ICU admission | 2.12 | 1.53–3.19 | <0.001 | 1.95 | 1.31–2.91 | 0.001 |

| Empiric antimicrobial therapy | 0.022 | 0.194 | ||||

| Beta-lactamic plus Macrolide | 1.69 | 1.17–2.45 | 0.006 | 1.43 | 0.97–2.12 | 0.070 |

| Fluoroquinolone plus Macrolide | 0 c | 0–ꚙ c | 0.953 | 0 c | 0–ꚙ c | 0.947 |

| Other treatment | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Age ≥65 years old | 2.69 | 1.69–4.29 | <0.001 | 2.85 | 1.74–4.68 | <0.001 |

| Smoking habit | 0.036 | – | – | – | ||

| No smoker | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Current smoker | 0.49 | 0.29–0.85 | 0.010 | – | – | – |

| Ex-smoker | 0.90 | 0.60–1.35 | 0.625 | – | – | – |

| Alcohol habit | 0.202 | – | – | – | ||

| No alcohol | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Current alcohol | 0.91 | 0.53–1.55 | 0.726 | – | – | – |

| Ex-alcohol | 1.76 | 0.92–3.39 | 0.090 | – | – | – |

| Pneumococcal vaccine | 0.58 | 0.34–0.98 | 0.044 | 0.44 | 0.26–0.75 | 0.003 |

| Previous systemic corticosteroids | 1.74 | 0.91–3.33 | 0.094 | – | – | – |

| Previous inhaled corticosteroids | 1.30 | 0.85–2.01 | 0.229 | – | – | – |

| Chronic cardiac disease | 1.56 | 0.96–2.53 | 0.070 | – | – | – |

| Chronic renal disease | 1.74 | 1.01–2.99 | 0.046 | – | – | – |

| Chronic liver disease | 2.01 | 1.13–3.58 | 0.018 | 2.30 | 1.28–4.15 | 0.005 |

| Chronic neurologic disease | 2.68 | 1.82–3.95 | <0.001 | 2.38 | 1.59–3.56 | <0.001 |

| Fever | 0.48 | 0.33–0.70 | 0.048 | 0.64 | 0.43–0.95 | 0.025 |

| Confusion | 2.93 | 2.02–4.25 | <0.001 | 1.81 | 1.22–2.67 | 0.003 |

| Creatinine (+1mg/Dl) | 1.35 | 1.23–1.48 | <0.001 | 1.37 | 1.21–1.55 | <0.001 |

| PCR (+1mg/Dl) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.246 | – | – | – |

| Lymphocytes count (+100cells/mm3) | 0.97 | 0.95–1.00 | 0.069 | – | – | – |

| Multilobar | 1.45 | 0.99–2.11 | 0.055 | – | – | – |

| Appropriate empiric antibiotic treatment | 0.50 | 0.30–0.84 | 0.008 | – | – | – |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. Data are shown as estimated HRs (95% CIs) of the explanatory variables in the 30-day mortality group. The HR is defined as the ratio of the hazard rates corresponding to the conditions described by two levels of an explanatory variable (the hazard rate is the risk of death [i.e., the probability of death], given that the patient has survived up to a specific time). The p-value is based on the null hypothesis that all HRs relating to an explanatory variable equal unity (no effect).

The variables analyzed in the univariable analyses were age, sex, smoking habit, alcohol habit, pneumococcal vaccine, influenza vaccine, systemic corticosteroid, inhaled corticosteroid, previous antibiotic, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic cardiovascular disease, chronic renal disease, chronic liver disease, diabetes mellitus, neurological disease, fever, confusion, creatinine, C-reactive protein, lymphocytes count, multilobar infiltration, and appropriate therapy.

The main findings of this study of a large population of immunocompetent hospitalized adult patients with CAP are the following: 1. Polymicrobial aetiology was identified in 14% of the overall population; 2. Polymicrobial aetiology was identified in 64% of hospitalized patients in the ward and in 36% of ICU patients; 3. S. pneumoniae and respiratory viruses were the most common pathogens; 4. Polymicrobial pneumonia presented with higher severity and more frequent complications and was associated with higher mortality than monomicrobial pneumonia; 5. Multilobar involvement was an independent predictor of polymicrobial aetiology, while fever was negatively associated with the likelihood of a polymicrobial aetiology; 6. Polymicrobial aetiology was an independent factor associated with 30-day mortality.

Identification of the microbial aetiology of CAP is vital. However, the causative microorganism is overall identified in fewer than 50% of cases, a circumstance that complicates the choice of appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy. In cases of suspected drug-resistant pathogens, broad-spectrum antibiotics are recommended. In some cases, broad-spectrum antibiotics are used unnecessarily, despite recent evidence of the association between these agents and poor outcomes in CAP patients.12,13 Despite the introduction of molecular tests for the rapid identification of pathogens and resistant genes in recent decades, the lack of standardization and limitation in the interpretation complicates their use in routine clinical practice. Recognizing patients at high risk of polymicrobial infection is important, as it determines whether the initiation of broader-than-usual spectrum empirical antimicrobial therapy is justified, as well as the need for isolation measures to prevent nosocomial spread in some cases.

In a previous study we reported that 11% of patients admitted to the ICU for severe CAP presented polymicrobial pneumonia.4 However, due to the small sample size we were unable to conclude whether the presence of polymicrobial aetiology was related to higher mortality in our study population. In the present study, 14% of our population presented polymicrobial aetiology; most of these cases (64%) were identified among ward patients, while in ICU patients the proportion was lower (36%). Similar results were reported in previous studies which found between 9% and 20% of CAP cases to be polymicrobial, and a similar proportion of polymicrobial cases were admitted to the ICU.5,6,14–17

S. pneumoniae and respiratory viruses were the most frequent pathogens related to pneumonia in our study. It was not a surprise to find that these microorganisms were common in both monomicrobial and polymicrobial pneumonia and in both ward and ICU patients. Other studies, including a recent systemic review, also reported that pneumococcus and respiratory viruses were the most frequent pathogens in CAP.2,3,14,15,18,19

In our study, cases of polymicrobial pneumonia were more severe and more likely to require ICU admission. They presented more complications, such as multilobar involvement, more frequently required invasive mechanical ventilation, had longer ICU and hospital stays, and had higher in-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year mortality. Our findings thus corroborate those of previous studies that reported associations between pneumonia due to co-infection and severe presentations and high mortality rates.5,6,20 Interestingly, patients with negative microbiology had lower rates of in-hospital and 30-day mortality compared to patients with monomicrobial or polymicrobial infections, which corroborates the results of a previous study by our research group that found no association between undiagnosed pneumonia and mortality.21 Polymicrobial aetiology was found to be an independent risk factor of 30-day mortality, alongside age≥65-years, chronic liver disease, chronic neurological disease, confusion, elevated creatinine levels, and ICU admission. This is in accordance with prior reports suggesting that the severity of pneumonia increases exponentially with age and number of comorbidities, which, in turn, increases the risk of death.1,22,23 The severity of the pneumonia, the higher rate of inadequate empiric antibiotic therapy, and the higher rate of complications in polymicrobial infections likely contribute to the high mortality rates, which do not largely differ from prior studies.4,12,24 Interestingly, pneumococcal vaccination and the presence of fever were factors associated with a lower risk of mortality in our study population, possibly because pneumococcal vaccination may reduce the risk of bacterial co-infection caused by the influenza virus and the risk of infection with resistant S. pneumoniae.25 As we reported in our study, the mortality in patients with co-infection was higher than in patients with monomicrobial infection. Our observation that fever was linked to a reduced risk of mortality supports the findings of an earlier study on PES (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacteriaceae extended-spectrum β-lactamase–positive, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) pathogens in pneumonia, which also reported that the presence of fever was associated with a lower risk of PES pathogens.26

Multilobar involvement and the absence of fever were the only risk factors for polymicrobial pneumonia identified in our multivariable analyses. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which have reported that polymicrobial infections can worsen outcomes, increase pneumonia severity, and elevate mortality rates in affected patients.20,27,28 For example, the study by Voiriot et al.27 reported that patients with polymicrobial pneumonia had higher rates of a complicated course, including a higher proportion of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), prolonged mechanical ventilation, and increased hospital mortality. The absence of fever was an unexpected finding, as fever is typically associated with infection. However, in cases of polymicrobial pneumonia, the immune response may be less effective or atypical due to the involvement of multiple pathogens. This absence of fever could reflect a more complex immune interaction, as demonstrated in the study by Schuurman et al.,29 which provided a nuanced assessment of the systemic host response in different CAP etiologies. It should be acknowledged that the identification of these two factors may not be sufficient at this point to justify the initiation of broader-spectrum empirical antimicrobial treatment. Although the multivariable model is well-fitted for polymicrobial aetiology, it has poor discrimination. Further studies are needed to validate and potentially broaden the risk factors that could help identify polymicrobial pneumonia with greater accuracy. Other limitations include the single-centre nature of the study, which may limit the generalizability of the findings; the complete diagnostic workup and microbiological sampling not uniformly applied in all patients given the real-life nature of our study; the potential underestimation of the true incidence of polymicrobial aetiology, as 22% of patients had received prior antibiotic therapy; and our definition of confirmed aetiology in cases of positive PCR for respiratory viruses in the upper airways, which may not be accurate, as we cannot be certain whether the detected virus is the cause of the infection or merely a bystander. This is particularly relevant in our study, as several factors identified as predictors of worse outcomes, such as increasing age and comorbidities, are also associated with delayed clearance of viral infections and increased risks of secondary bacterial infections. Finally, we did not include cases of SARS-CoV-2 to avoid its potential effect on outcomes, particularly during the first and second waves of the pandemic.

In conclusion, polymicrobial CAP is common among hospitalized adult patients. Polymicrobial pneumonia is often severe and associated with high mortality. As S. pneumoniae and respiratory viruses are the main causative agents of polymicrobial pneumonia, strengthening vaccination strategies should be a key approach to addressing this serious form of CAP.

Authors’ ContributionsConceptualization and methodology: CC, DC, AG, MF, MA, AT. Data curation and investigation: CC, AG, AP, DC. Writing—original draft: CC, DC, AG, MA, AP, MF, AT. Writing-review & editing: CC, DC, AT.

FundingThis study was supported by CIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES CB06/06/0028), and by 2009 Support to Research Groups of Catalonia 911, IDIBAPS. The founders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, writing of the report, or decision to submit for publication.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Not applicable.