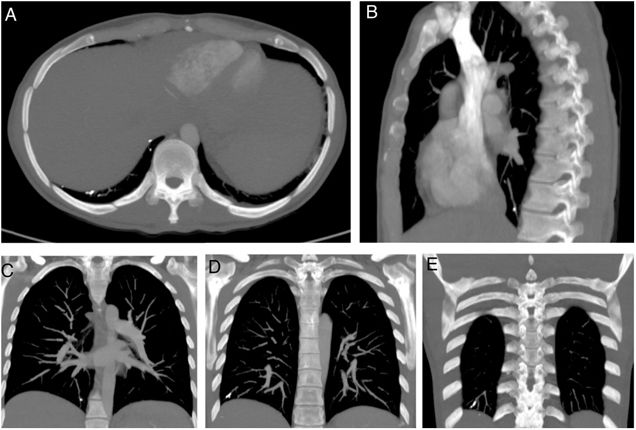

Our patient was a 37-year-old woman who attended the emergency department after a fainting episode at home, accompanied by sudden dyspnea, pleuritic pain, and headache. Her history was significant for pelvic vein embolization for pelvic congestion syndrome 24h previously. ECG showed right bundle branch block and D-dimer levels were 2504ng/mL. Pulmonary artery CT showed the subsegmental branch occupied by a foreign body of metal density consistent with N-2-butyl cyanocrylate and lipiodol®, without pulmonary infarction. A bubble echocardiogram ruled out the existence of patent foramen ovale. Because the patient was symptomatic, we decided to anticoagulate with low molecular weight heparin at therapeutic doses for 3 months, with clinical and radiological follow-up. She is currently asymptomatic (Fig. 1).

Although rare, cases of unwanted embolization of metal material (e.g. coils) from treated pelvic varices migrating to the pulmonary circulation have been described in the literature.1 As medical professionals we must be aware of the potential undesirable risks of embolization with the various endovascular materials used in interventional procedures in the venous system, and we must also bear in mind the possibility of cerebrovascular accident associated with an undiagnosed patent foramen ovale.2

Although at first sight, anticoagulant therapy may appear to be of little use in the treatment of a non-resorbable material that differs in nature from that generated by physiological hemostasis, we proposed this treatment on the premise that the anti-inflammatory action of heparin would prevent endothelial damage in the multiple distal subsegmental branches and progression to the Virchow triad, helping in turn to prevent pulmonary infarction. We also took into account the patient's low hematological risk, and the risk of more undesirable embolization caused by material migrating from the pelvis. When the patient was re-evaluated 3 months later with CT angiogram, we agreed that continuing anticoagulation would be of no further benefit. Current clinical practice guidelines do not specifically address this issue,3 but it is likely to become more common given the exponential growth of the different venous interventional procedures. We believe that patients who are candidates for treatments of this kind should be informed about the possible adverse effects.