Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare, low grade, metastasizing, multisystem neoplasm, associated with lung cyst formation, pneumothoraces, renal angiomyolipomas and chylous effusions.1,2 Women during reproductive years are predominantly affected, and recent reports show this condition may affect up to data suggest prevalence to be 20.9–26.04 women per million.3 LAM occurs sporadically or in association with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).4 Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis gene result in the activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 pathway.5 Discovery of the genetic basis for LAM led to the successful targeting of the mTOR pathway with mTOR inhibitors, such as sirolimus.6 The diagnostic approach to LAM pursues the least invasive means possible. In the setting of typical lung imaging and any of TSC, renal angiomyolipoma, cystic lymphangioleiomyoma or chylous fluid collections, a serum vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D) of ≥800pg/ml can avoid the need for lung biopsy.7

The ATS/JRS guidelines advise commencing treatment with mTOR inhibitors for patients with LAM that have abnormal lung function, defined as a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of less than 70% predicted, or chylous fluid accumulations.7 This is based on the successful results of the MILES trial where sirolimus slowed lung function decline compared to placebo.8 While it is evident that those with abnormal lung function will likely benefit form mTOR inhibitors many questions remain, including how long to continue treatment, other indications and whether to commence all patient on mTOR inhibitors (Fig. 1).

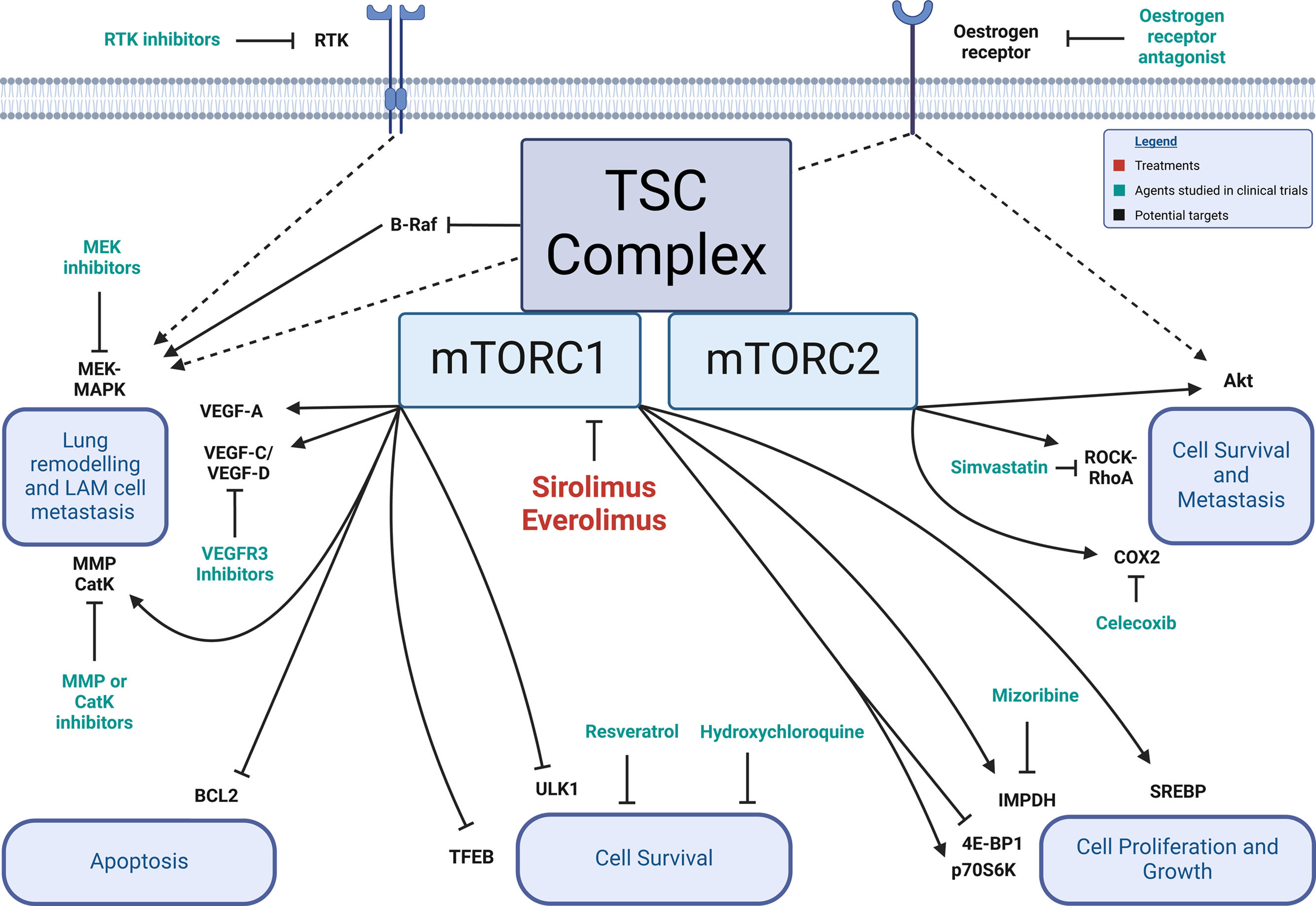

Dysregulated signaling pathways in LAM pathogenesis highlight potential targets for clinical trials. Mutations in mTORC1 pathways upregulate IMPDH, SREBP, VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, MMPs, and CatK; and inhibit 4E-BP1, ULK1, TFEB, and BCL2. mTORC2 activates Akt, ROCK–RhoA, and COX2. Oestrogen stimulates activation of MEK–MAPK and Akt. RTKs mediate activation of MEK–MAPK signalling. Dysregulated mTOR signalling in LAM cells alters the cell behaviours shown in blue boxes. Agents studied in clinical trials are shown in green. Potential trial targets are shown in black. 4E-BP1: eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1; Akt: AKT serine–threonine protein kinase; BCL2: B-cell lymphoma 2; B-Raf: V-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homologue B1; CatK: cathepsin K; COX2: cyclooxygenase 2; IMPDH: inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase; LAM: lymphangioleiomyomatosis; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK: MAPK kinase; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; mTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin; mTORC1: mTOR complex 1; p70S6K: 70kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase; RhoA: Ras homologue family member A; ROCK: Rho-associated protein kinase; RTK: receptor tyrosine kinase; SREBP: sterol regulatory element-binding protein; TFEB: transcription factor EB; TSC: tuberous sclerosis complex; ULK1: Unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

While the safety profile has been demonstrated in follow up studies over many years, how long patients should remain on mTOR inhibitor remains unclear.9 Serum VEGF-D concentrations correlate with disease severity in some patients and can perhaps guide treatment response.8 Menopausal status has a significant effect on disease progression, with reduced rate of FEV1 decline in post-menopausal women, however both pre- and post-menopausal groups demonstrate treatment response so this remains unclear whether post-menopausal women should discontinue mTOR therapy.10 In the setting of normal spirometry, mTOR therapy should be considered if there are other markers of severity, specifically rapidly reducing FEV1, elevated residual volume, reduced diffusing capacity, exercise-induced desaturation or resting hypoxaemia.11 Whether all patients with LAM and history of pneumothorax should commence mTOR inhibitor is open for debate, but recent data suggests up to 80% reduction in pneumothorax recurrence.12

Timing of treatment commencement in patients with FEV1 of greater than 70% and selecting those at risk of lung function decline is challenging, leading to the need for better prediction models to identify those with progressive disease.13 Indeed, the ongoing Multicenter Interventional Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) Early Disease Trial (MILED) is designed to determine whether early initiation of sirolimus is effective in preventing disease progression in patients with FEV1 >70%.14 The identification of new prognostic and predictive biomarkers may aid with timing of treatment commencement and importantly mTOR inhibitors serve only to stabilise lung function, they cannot reverse damage, not all patients respond to treatment and continue to decline, therefore novel and more effective therapies are needed for LAM.

Conflict of InterestNo author has any conflict of interest to declare related to this work.