There is scarce information about the most used mucolytic drug in bronchiectasis N-acetylcysteine (N-AC). Our objective was to analyze the effect of N-AC with respect to some outcomes in bronchiectasis.

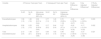

MethodsAmbispective, longitudinal, observational, multi-center (43 centers) study of a cohort of 2461 adult patients diagnosed with bronchiectasis. Those patients treated in a stable situation with at least 600mg/d of N-AC (368; 15%) for at least 6 months were compared with patients not receiving this treatment. The variables analyzed and compared were those available two years before and after treatment. ANCOVA analysis was used to analyze the effect of N-AC as the inter-group difference of the basal intra-group difference for each variable, adjusted for relevant covariables.

ResultsThe N-AC group showed a full adjusted improvement of 27% in exacerbations, 17% in hospitalizations, and 31% in total exacerbation rates compared with the no-N-AC group. Moreover, a decrease in the volume of sputum production of 59.7% was observed as well as a decrease of 12% of patients with bronchial infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA). The use of 1200mg/d (n=116) resulted in only a mild, albeit significative improvement in the exacerbation rate compared with the use of 600mg/d (-11% in absolute number). Both doses were well tolerated.

ConclusionN-AC (in most cases at a dose of 600mg/d) is safe and effective and sufficient to reduce both the number of exacerbations and hospitalizations and the purulence and volume of sputum, as well as the isolation rate of PA in patients with bronchiectasis.