The main objective was to analyze the short, medium, and long-term effectiveness of a clinical–psychological care protocol for smoking cessation using cytisinicline. Other secondary objectives were evaluate safety and whether the characteristics of smoking, adherence, and the intensity of craving and withdrawal syndrome at 4th week were associated with effectiveness.

MethodsObservational, prospective, multicenter study that includes smokers motivated to quit evaluated in twelve Smoking Cessation Services in Spain.

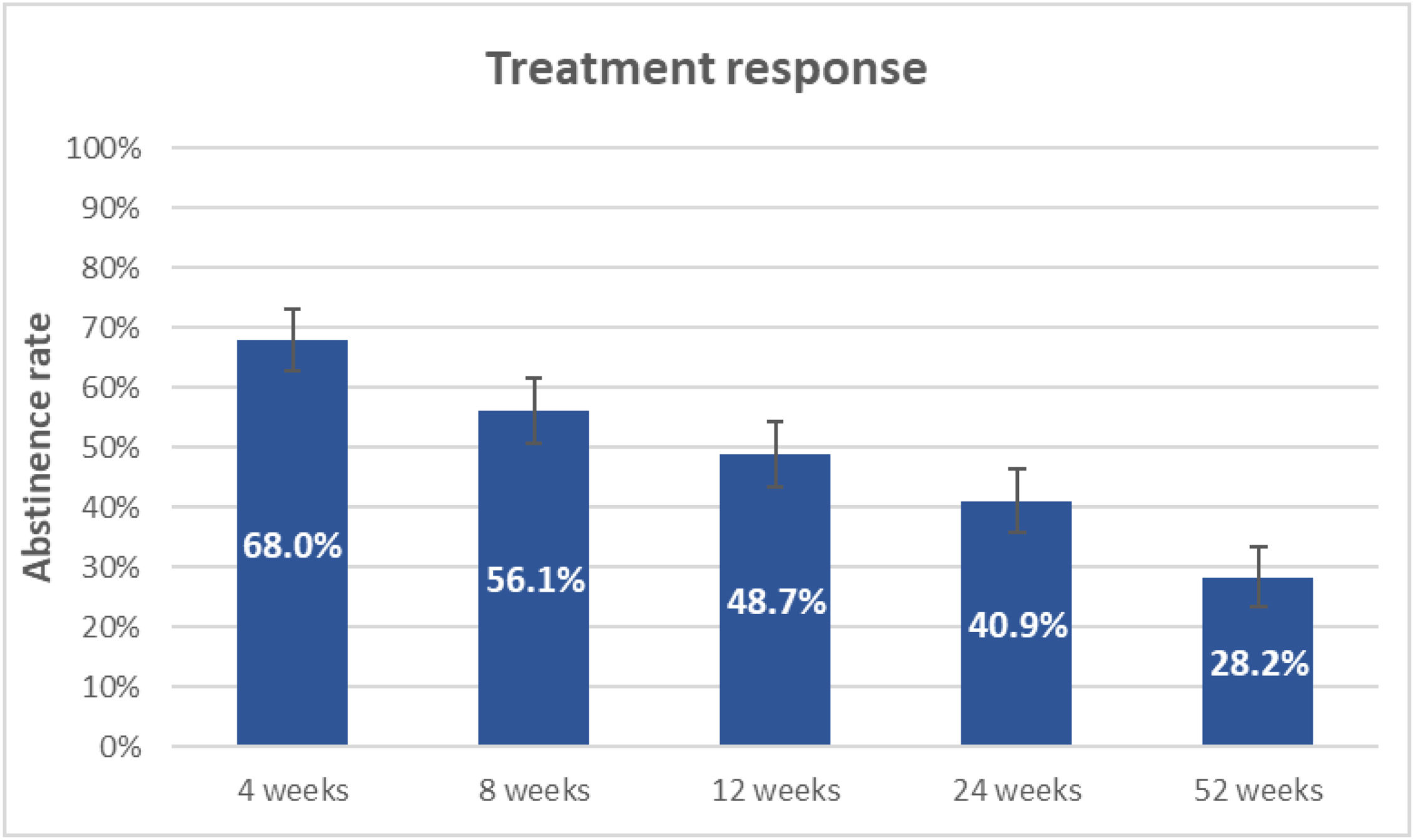

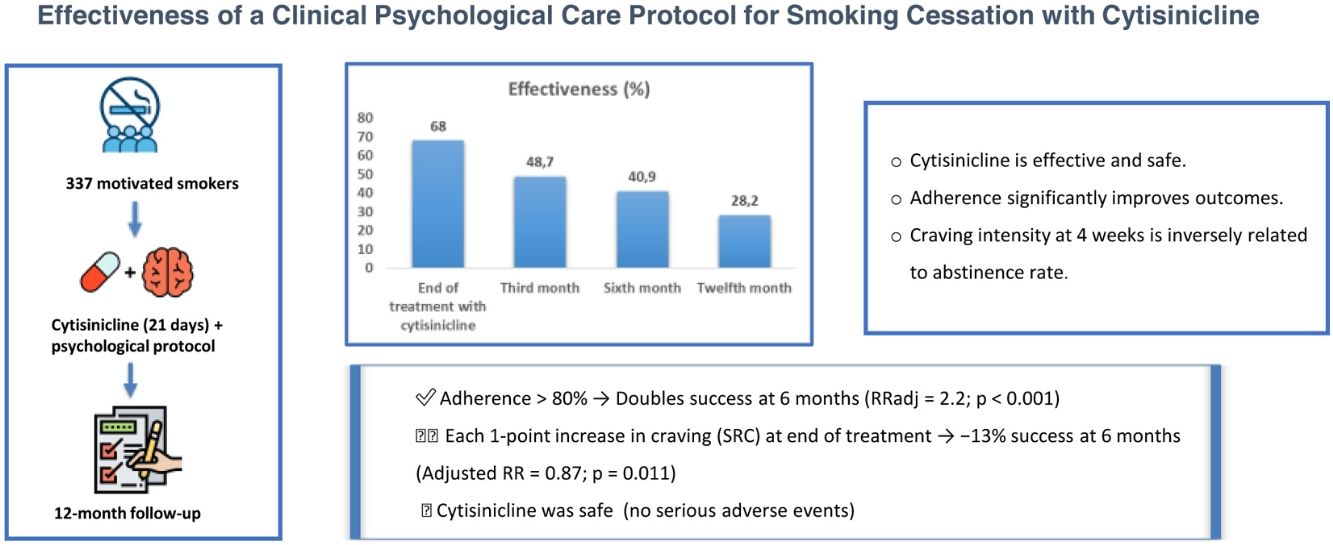

ResultsA total of 337 smokers were studied. Effectiveness of cytisinicline was 68% at the end of treatment, but was reduced to 48.7%, 40.9% and 28.2%, at 3rd, 6th and 12th month of follow up respectively. The measurement of adherence and the intensity of craving by SRC showed statistically significant association with effectiveness at 24th week, RRadj=2.2 (p<0.001) and RRadj=0.87 (p=0.011) respectively. Common adverse effects (occurring in more than 10% of patients) were: sleep disorders, headaches, dizziness and digestive disorders.

ConclusionsThe effectiveness of protocol was 68% at the end of treatment, but was reduced to 48.7%, 40.9% and 28.2% at 3rd, 6th and 12th months respectively. Subjects who met more than 80% of treatment adherence doubled their chances of success at 6th month. For each point of craving intensity, measured by the SRC, at the end of the pharmacological treatment the chances of success at 6th month were reduced by 13%. Cytisinicline was safe.

Tobacco consumption is one of the most serious public health problems globally, with important consequences for health, economy, and environment. It is a chronic, addictive, and relapsing disease that has a high prevalence [1,2].

Those smokers who want to quit should be offered treatment. The combination of psychological counseling and pharmacological treatment is the most effective therapeutic measure for smoking cessation [2]. Some medications have been shown to be safe and effective in helping smokers to quit: nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion, and partial nicotinic receptor agonists (varenicline and cytisinicline) [3].

Cytisinicline is an alkaloid that originates from the extract of the seeds of the trees of the species Cytisus laburnum and Cytisus sophorae. Its effectiveness is due to the fact that it acts as a selective partial agonist of α4β2 nicotinic receptors. By acting as an agonist, it activates these receptors and produces a moderate release of dopamine that reduces the symptoms of withdrawal syndrome; and by acting as an antagonist, it prevents the binding of nicotine to these receptors, reducing the pleasurable sensation that occurs when smoking [4,5].

Different meta-analyses carried out with this drug indicate that cytisinicline used at its usual doses for a period of 25 days increases the chances of quitting smoking compared to placebo [3,4,6–12]. One of the most recent, carried out with a total of 6 clinical trials in which 5194 smokers participated, shows cytisinicline is more effective than placebo: [RR]=2.65, 95% [CI]=1.50–4.67 [8].

Cytisinicline was marketed in Spain in November 2021. Shortly thereafter, a multidisciplinary group of Spanish health professional agreed on a clinical–psychological care protocol for treatment with this medication [13]. Subsequently, an observational, multicenter, multidisciplinary, and cross-sectional study was carried out on a total of 105 smokers who had received the medication at standard doses for 25 days. This study found that at the end of the treatment, 77.1% of the patients were satisfied with it, 82.5% of the patients had good adherence, and it was well tolerated. 76% of patients were abstinent after 25 days of treatment [14]. However, in our country, we do not have broader data on effectiveness and safety in the medium and long term in daily clinical practice using this medication. For this reason, the Research Program on Tobacco Control of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) proposed a large multicenter project to assess the effectiveness and safety of the use of cytisinicline for smoking cessation, applying the clinical–psychological care protocol agreed upon by the Spanish health professional group [13].

MethodsObservational, prospective, multicenter study that includes smokers motivated to quit evaluated in twelve smoking cessation services in Spain. Patients were recruited from December 1, 2022 to December 31, 2023, and completed one year of follow-up. This project was approved by the CEIm of the Alcorcon Foundation University Hospital (2022, CEIm-22/64) and subsequently by the other CEIm of participating centers.

The main objective was to analyze the short, medium, and long-term effectiveness (52 weeks) of a clinical–psychological care protocol for smoking cessation using cytisinicline in smokers motivated to quit.

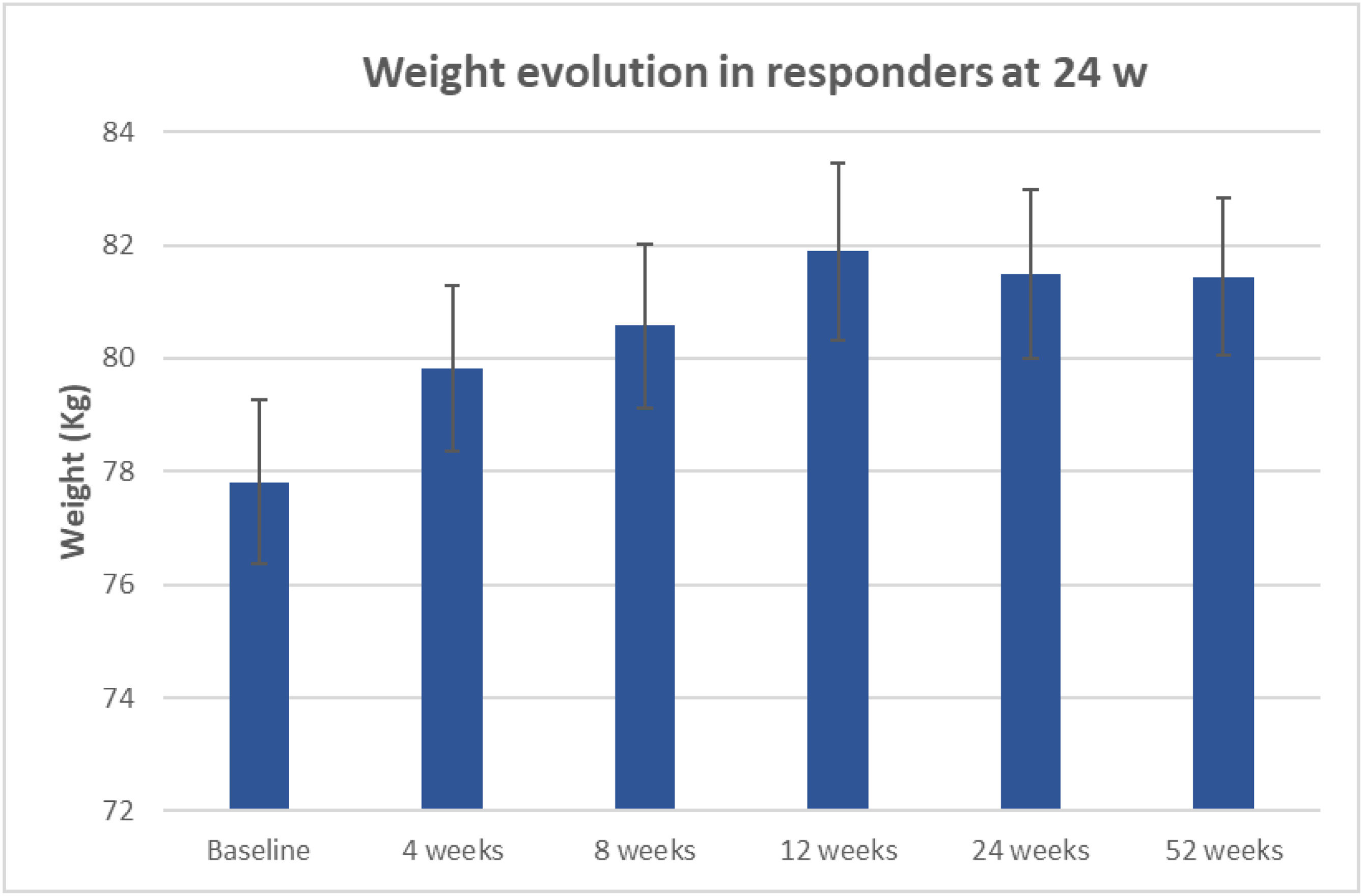

The secondary objectives were as follows: (a) estimate the degree of adherence and satisfaction with medication, (b) evaluate whether the characteristics of smoking, adherence, and the intensity of craving and withdrawal syndrome at 4 weeks are associated with effectiveness, (c) analyze the evolution of craving and withdrawal syndrome during the use of the medication and up to 12th week based on the characteristics of smoking and effectiveness, (d) evaluate safety, and (e) analyze the evolution of weight in abstinent patients.

All smokers between 18 and 65 years of age who attended the smoking cessation service of the participating centers, were motivated to quit, and agreed to participate in the study were recruited. All patients presenting contraindications, as defined by the indications approved by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS) [15], were excluded from the study.

A total of eight clinical visits were made: one baseline visit, two follow-up visits during the 25 days of treatment (6–8 days and 16–18 days), and five post-medication follow-up visits (4th, 8th, 12th, 24th, and 52nd weeks) [13].

At the initial visit, demographic, clinical, and comorbidity data were collected, a detailed smoking history was taken, and the following characteristics were evaluated: (a) Motivation and self-efficacy using a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 10. Patients who scored 8 or higher on the VAS were considered to demonstrate a high level of motivation and self-efficacy toward smoking cessation [16], (b) physical dependence through the Fagerström test for cigarette dependence (FTCD) [17–19] and time to first cigarette (TFC) [20], (c) reward through the Fagerström reinforcement question (FRQ) [21], (d) psychic dependence with the questionnaire of Unit of Public Health Institute of Madrid (UISPM Questionnaire) [16], (e) craving using the single rating of craving (SRC) [22], (f) nicotine withdrawal syndrome using the Minnesota nicotine withdrawal scale (MNWS) [23] and (g) smoking level (classified into four categories using two objective parameters: the pack-year index and the CO levels: Mild: pack-years<5 and exhaled CO<15ppm, moderate: 5–15 pack-years and CO between 15 and 20ppm, severe: 16–25 pack-years and CO between 21 and 30ppm and very severe: >25 pack-years and CO>30ppm) [16].

Until the 4th week, data on adherence (use of >80% of the recommended doses), satisfaction with the medication (using a 5-point Likert scale), and the presence and intensity of adverse effects were analyzed.

Effectiveness was evaluated at all follow-up visits. Continuous abstinence rate was used. It was defined as the number of patients who do not smoke a single cigarette from 15 days after the start of pharmacological treatment. At all visits, abstinence was validated by measuring CO levels in exhaled air. Less than 10ppm was required to consider the patient a nonsmoker [24,25]. Nicotine withdrawal syndrome and craving were assessed at all follow-up visits through the 12th week.

Statistical analysisSample size was calculated according to response rate. A total of 325 patients were necessary to estimate a response of 30% [6,26,27], with a 95% confidence interval and 5% estimation error.

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 27.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and STATA 17 (Stata Corp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LLC), with statistical significance defined as a p-value<0.05. Counts and relative frequencies were used to describe qualitative variables distribution and mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) in case of quantitative variables.

Adherence, satisfaction, and response rates were calculated, and the 95% confidence interval (CI 95%) was estimated with the Wilson method. Abstinence was assessed using an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach, in which all participants initially enrolled were included in the final analysis. In line with a “worst-case scenario” strategy, individuals lost to follow-up, who did not attend follow-up visits, despite repeated attempts to reschedule, were classified as non-abstinent. To examine differences in baseline data among the groups defined by adherence at the 4th week, we applied the chi-squared test in the case of qualitative variables and the t-test or U Mann Whitney test for two independent samples in the case of quantitative data. Lost to follow-up patients at the 4th week were considered non-adherent.

In a sample of patients followed at the 4th week, we analyzed the effect in response to smoking level, dependence level (FTCD≥7, TFC<30), treatment adherence, craving, and abstinence syndrome. We estimated the risk ratio adjusted (RRadj) by gender, age, and comorbidities with multivariate modified Poisson regression with robust errors.

Mixed models were estimated to study craving and abstinence syndrome evolution over time. Models included follow-up (baseline, 6–8 days, 16–18 days, and 4th, 8th, and 12th weeks) as repeated measures, smoking level, dependence level, and effectiveness as factor covariates, and their first-level interaction with follow-up; gender, age, comorbidities, and adherence were included as adjustment covariates. Mixed models were also used to analyze weight evolution.

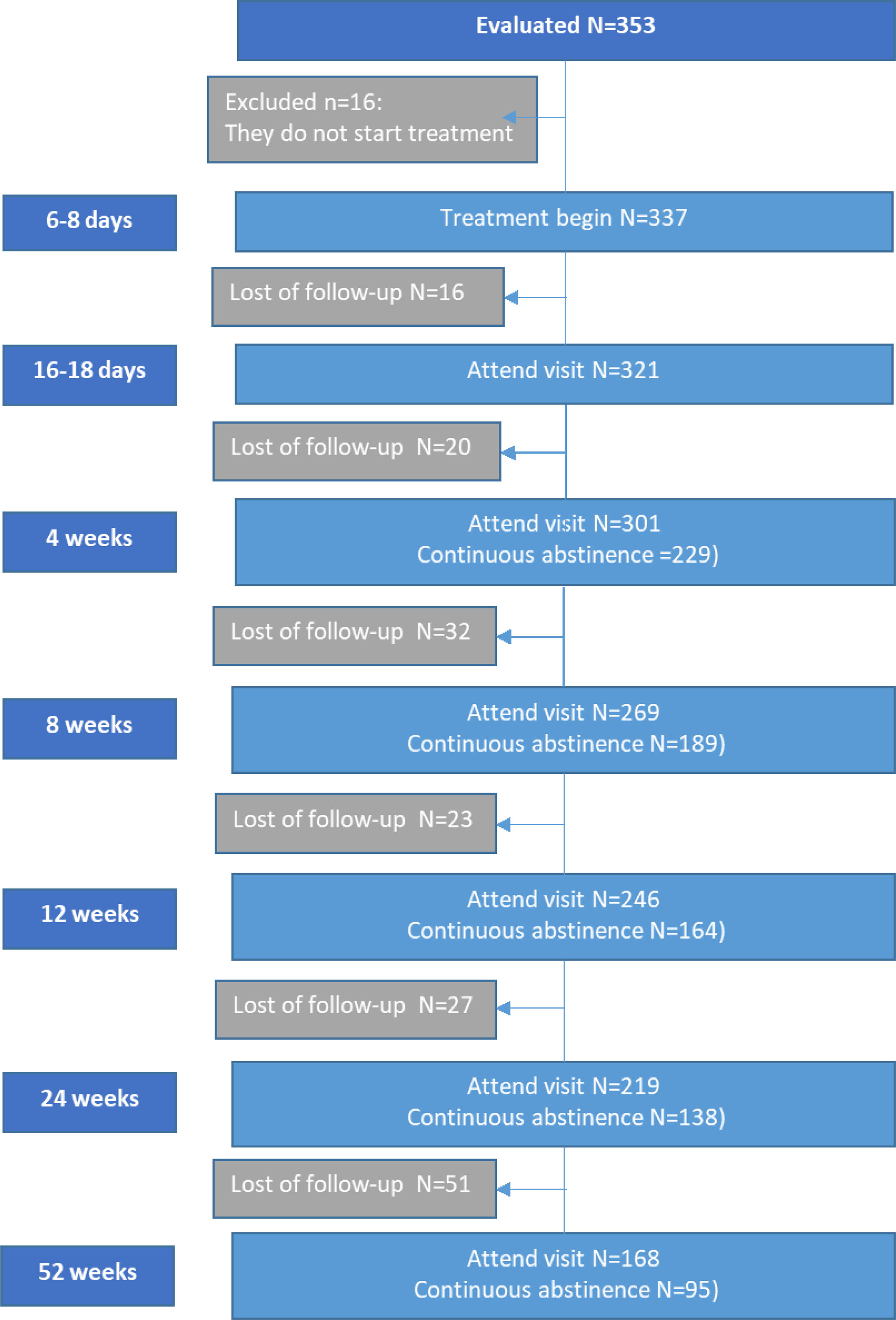

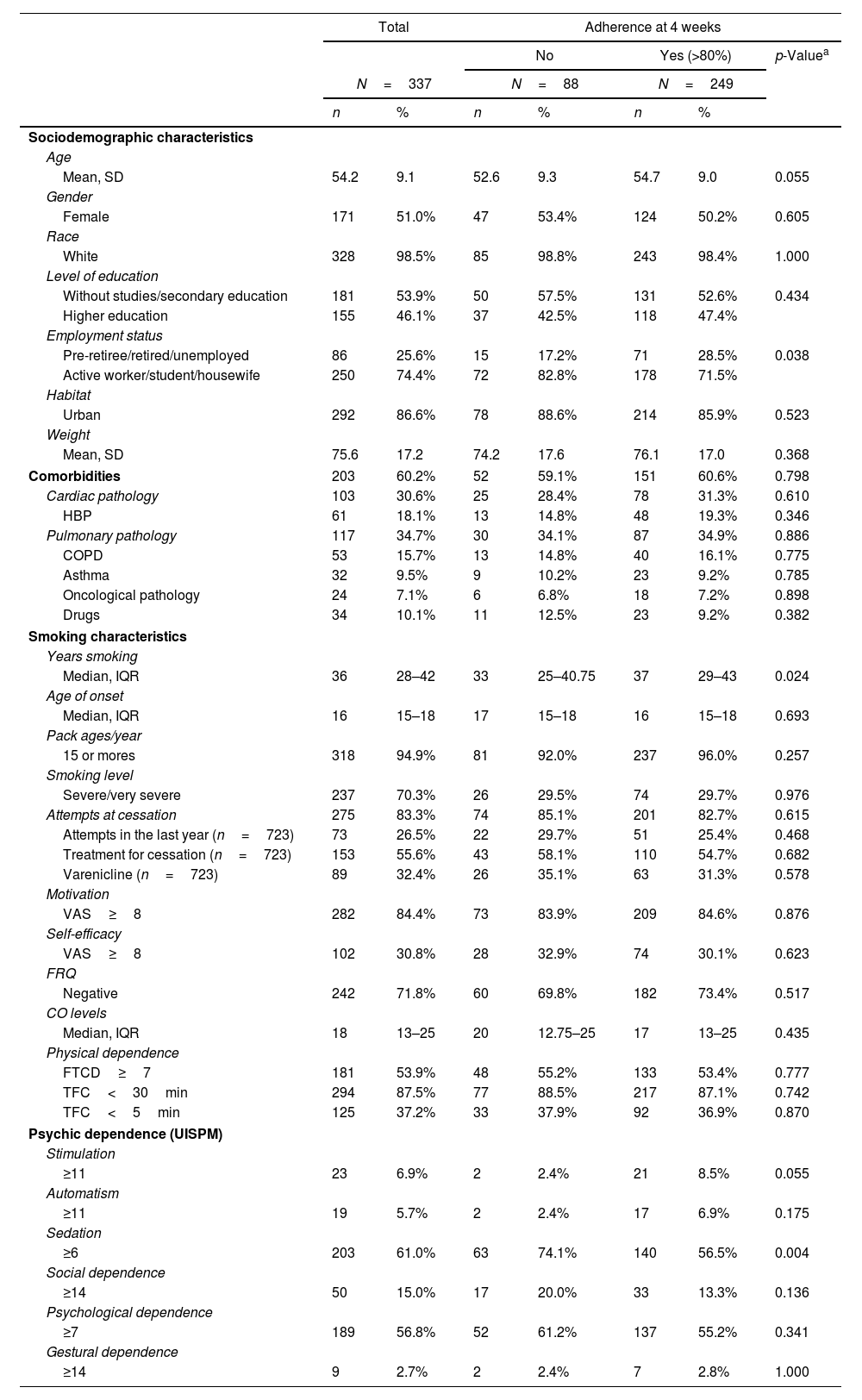

ResultsSociodemographic characteristicsA total of 337 patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the study. The greatest number of losses to follow-up occurs from visit 4 after drug withdrawal (Fig. 1 (flow chart)). The following sociodemographic characteristics of the sample should be highlighted: average age 54.2 (9.1) years, 51% women. 60% of the patients had some comorbidity. 70% had severe smoking, 54% had a high degree of nicotine dependence measured as FTCD≥7, and 87% measured as TFC<30min. 84% had high motivation (VAS≥8) to make a quit attempt, but only 31% reported high self-efficacy (VAS≥8). 83% of patients had made previous attempts, and of them, 27% had done so in the last year, and only 56% had used pharmacological treatment in quit attempts, varenicline being the most used medication (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of study participants. Comparison of sample characteristics according to adherence.b

| Total | Adherence at 4 weeks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes (>80%) | p-Valuea | |||||

| N=337 | N=88 | N=249 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Mean, SD | 54.2 | 9.1 | 52.6 | 9.3 | 54.7 | 9.0 | 0.055 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 171 | 51.0% | 47 | 53.4% | 124 | 50.2% | 0.605 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 328 | 98.5% | 85 | 98.8% | 243 | 98.4% | 1.000 |

| Level of education | |||||||

| Without studies/secondary education | 181 | 53.9% | 50 | 57.5% | 131 | 52.6% | 0.434 |

| Higher education | 155 | 46.1% | 37 | 42.5% | 118 | 47.4% | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Pre-retiree/retired/unemployed | 86 | 25.6% | 15 | 17.2% | 71 | 28.5% | 0.038 |

| Active worker/student/housewife | 250 | 74.4% | 72 | 82.8% | 178 | 71.5% | |

| Habitat | |||||||

| Urban | 292 | 86.6% | 78 | 88.6% | 214 | 85.9% | 0.523 |

| Weight | |||||||

| Mean, SD | 75.6 | 17.2 | 74.2 | 17.6 | 76.1 | 17.0 | 0.368 |

| Comorbidities | 203 | 60.2% | 52 | 59.1% | 151 | 60.6% | 0.798 |

| Cardiac pathology | 103 | 30.6% | 25 | 28.4% | 78 | 31.3% | 0.610 |

| HBP | 61 | 18.1% | 13 | 14.8% | 48 | 19.3% | 0.346 |

| Pulmonary pathology | 117 | 34.7% | 30 | 34.1% | 87 | 34.9% | 0.886 |

| COPD | 53 | 15.7% | 13 | 14.8% | 40 | 16.1% | 0.775 |

| Asthma | 32 | 9.5% | 9 | 10.2% | 23 | 9.2% | 0.785 |

| Oncological pathology | 24 | 7.1% | 6 | 6.8% | 18 | 7.2% | 0.898 |

| Drugs | 34 | 10.1% | 11 | 12.5% | 23 | 9.2% | 0.382 |

| Smoking characteristics | |||||||

| Years smoking | |||||||

| Median, IQR | 36 | 28–42 | 33 | 25–40.75 | 37 | 29–43 | 0.024 |

| Age of onset | |||||||

| Median, IQR | 16 | 15–18 | 17 | 15–18 | 16 | 15–18 | 0.693 |

| Pack ages/year | |||||||

| 15 or mores | 318 | 94.9% | 81 | 92.0% | 237 | 96.0% | 0.257 |

| Smoking level | |||||||

| Severe/very severe | 237 | 70.3% | 26 | 29.5% | 74 | 29.7% | 0.976 |

| Attempts at cessation | 275 | 83.3% | 74 | 85.1% | 201 | 82.7% | 0.615 |

| Attempts in the last year (n=723) | 73 | 26.5% | 22 | 29.7% | 51 | 25.4% | 0.468 |

| Treatment for cessation (n=723) | 153 | 55.6% | 43 | 58.1% | 110 | 54.7% | 0.682 |

| Varenicline (n=723) | 89 | 32.4% | 26 | 35.1% | 63 | 31.3% | 0.578 |

| Motivation | |||||||

| VAS≥8 | 282 | 84.4% | 73 | 83.9% | 209 | 84.6% | 0.876 |

| Self-efficacy | |||||||

| VAS≥8 | 102 | 30.8% | 28 | 32.9% | 74 | 30.1% | 0.623 |

| FRQ | |||||||

| Negative | 242 | 71.8% | 60 | 69.8% | 182 | 73.4% | 0.517 |

| CO levels | |||||||

| Median, IQR | 18 | 13–25 | 20 | 12.75–25 | 17 | 13–25 | 0.435 |

| Physical dependence | |||||||

| FTCD≥7 | 181 | 53.9% | 48 | 55.2% | 133 | 53.4% | 0.777 |

| TFC<30min | 294 | 87.5% | 77 | 88.5% | 217 | 87.1% | 0.742 |

| TFC<5min | 125 | 37.2% | 33 | 37.9% | 92 | 36.9% | 0.870 |

| Psychic dependence (UISPM) | |||||||

| Stimulation | |||||||

| ≥11 | 23 | 6.9% | 2 | 2.4% | 21 | 8.5% | 0.055 |

| Automatism | |||||||

| ≥11 | 19 | 5.7% | 2 | 2.4% | 17 | 6.9% | 0.175 |

| Sedation | |||||||

| ≥6 | 203 | 61.0% | 63 | 74.1% | 140 | 56.5% | 0.004 |

| Social dependence | |||||||

| ≥14 | 50 | 15.0% | 17 | 20.0% | 33 | 13.3% | 0.136 |

| Psychological dependence | |||||||

| ≥7 | 189 | 56.8% | 52 | 61.2% | 137 | 55.2% | 0.341 |

| Gestural dependence | |||||||

| ≥14 | 9 | 2.7% | 2 | 2.4% | 7 | 2.8% | 1.000 |

Values expressed as Mean (SD), median (IQR), standard deviation: SD, interquartile range: IQR, carbon monoxide: CO, high blood pressure: HBP, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: COPD, visual analog scale: VAS, Fagerström test for cigarette dependence: FTCD, time to first cigarette: TFC, Fagerström Reinforcement Question: FRQ and Questionnaire of Unit of Public Health Institute of Madrid (UISPM).

Adherence to treatment was very high; more than 80% of patients took more than 80% of the prescribed tablets. Adherence remained constant during treatment with 85.5%, 83.9%, and 82.7% in the first three follow-up visits. When comparing the characteristics of the sample according to adherence, we found that adherent patients were more frequently active workers, had been smoking for more years, and had a lower degree of sedation. No significant differences were observed in the rest of the clinical, demographic, or smoking characteristics (Table 1).

The majority of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with the treatment (4 or 5 on the Likert scale) in 80.8%, 83.8% and 82.8% during the first three follow-up visits.

Continuous abstinence rateContinuous abstinence rate at the end of treatment (4th week) was 68% (95% CI: 62.7–72.9%), but this progressively decreased until reaching 28.2% (95% CI: 23.4–33.3%) at the 52nd week (Fig. 2).

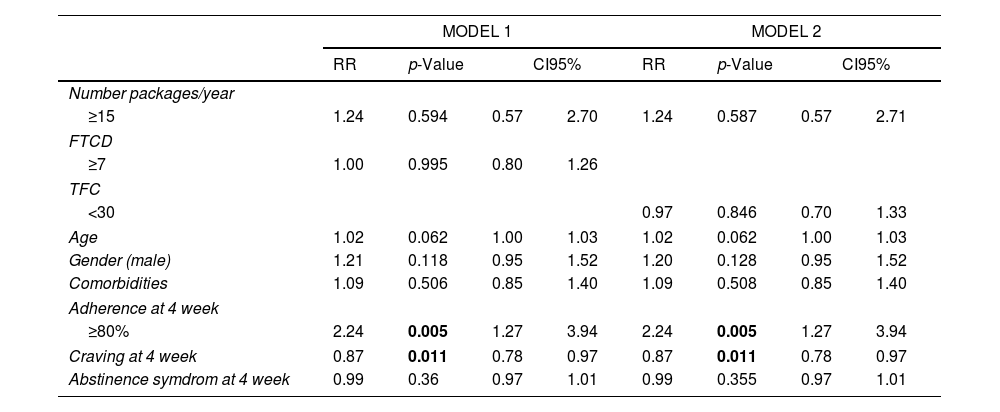

In the sample of patients with follow-up at the 4th week (n=299), the measurement of adherence and the intensity of craving by SRC showed a statistically significant association with effectiveness at the 24th week, RRadj=2.2 (p<0.001) and RRadj=0.87 (p=0.011), respectively. That means those smokers who complied with more than 80% of adherence multiplied by 2.2 their possibilities to quit at the 24th week in comparison with those who did not comply (RRadj=2.2); and for each point in the measurement of SRC at the 4th week, the patient decreased 13% of his chances to keep abstinence at the 24th week. (RRadj=0.87). We found no association between abstinence and smoking level, nicotine dependence level, or measurement of MNWS (Table 2).

Effect in response of smoking level, dependence level, treatment adherence, craving and abstinence syndrome, adjusted by gender, age, comorbidities. Multivariate modified Poisson regression models. Model 1 include FTCD as dependence level and model 2 include TFC as dependence model.

| MODEL 1 | MODEL 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | p-Value | CI95% | RR | p-Value | CI95% | |||

| Number packages/year | ||||||||

| ≥15 | 1.24 | 0.594 | 0.57 | 2.70 | 1.24 | 0.587 | 0.57 | 2.71 |

| FTCD | ||||||||

| ≥7 | 1.00 | 0.995 | 0.80 | 1.26 | ||||

| TFC | ||||||||

| <30 | 0.97 | 0.846 | 0.70 | 1.33 | ||||

| Age | 1.02 | 0.062 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.062 | 1.00 | 1.03 |

| Gender (male) | 1.21 | 0.118 | 0.95 | 1.52 | 1.20 | 0.128 | 0.95 | 1.52 |

| Comorbidities | 1.09 | 0.506 | 0.85 | 1.40 | 1.09 | 0.508 | 0.85 | 1.40 |

| Adherence at 4 week | ||||||||

| ≥80% | 2.24 | 0.005 | 1.27 | 3.94 | 2.24 | 0.005 | 1.27 | 3.94 |

| Craving at 4 week | 0.87 | 0.011 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.011 | 0.78 | 0.97 |

| Abstinence symdrom at 4 week | 0.99 | 0.36 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.355 | 0.97 | 1.01 |

Risk ratio: RR, confidence Interval 95%: CI95%, Fagerström test for cigarette dependence: FTCD, time to first cigarette: TFC.

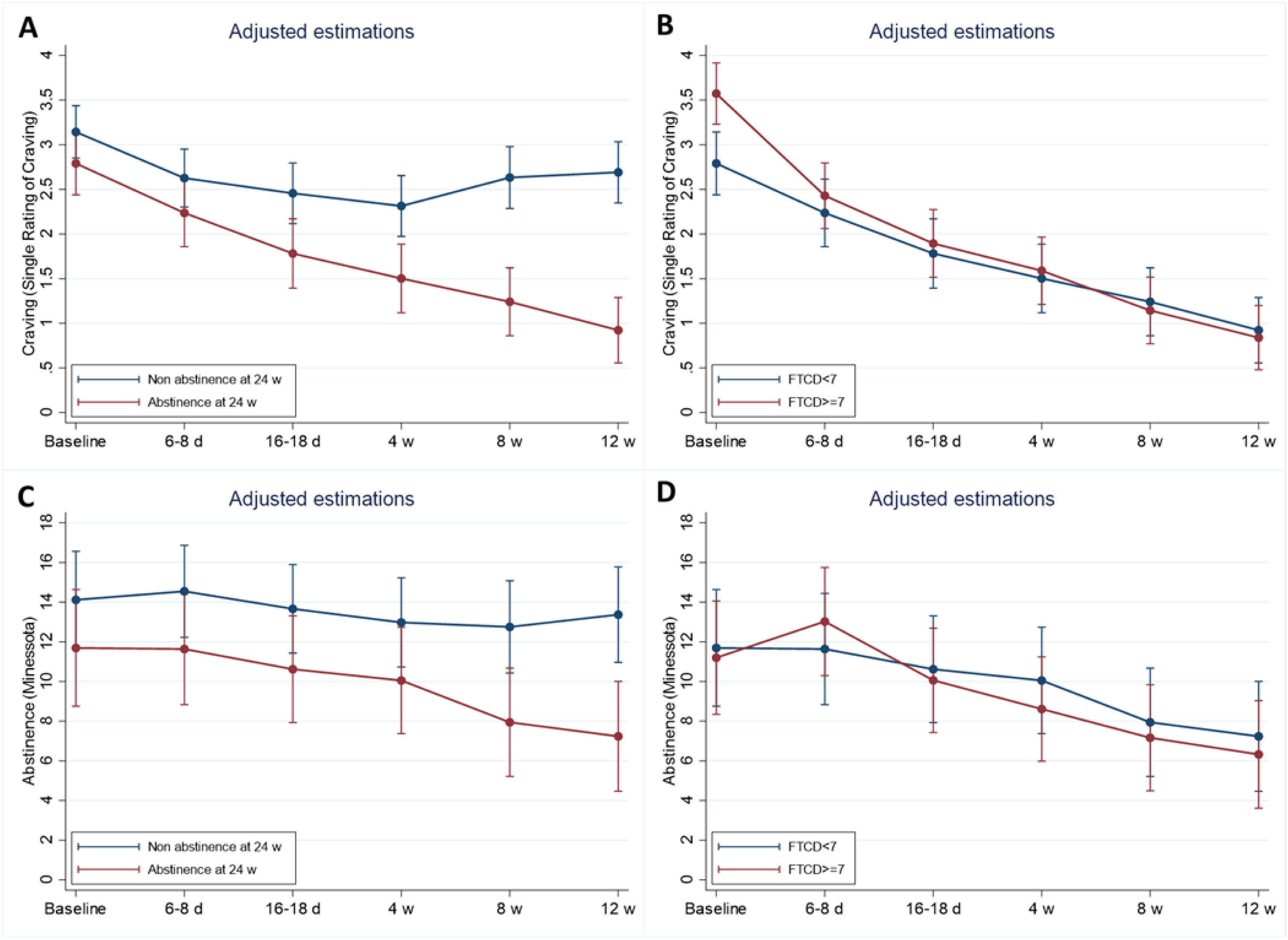

There was a significant decrease over time to the 12th week in craving (p<0.001). This decrease was similar by smoking level (interaction effect p=0.719), but higher in patients with FTCD≥7 (interaction effect p<0.001) and abstinence at 24th week (interaction effect p<0.001). Responder patients showed an additional decrease from baseline at the 4th and 12th weeks of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.06–0.86, p=0.025) and 1.42 (95% CI: 1–1.79, p<0.001), respectively. Patients with a higher dependence level showed an additional decrease at the 4th and 12th weeks of 0.7 (95% CI: 0.3–1.09, p=0.001) and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.5–2.23, p<0.001), respectively (Fig. 3A and B).

Craving and abstinence syndrome evolution over time by treatment response and psychical dependence group. Estimations adjusted with mixed models including adherence, gender, age and comorbidities as adjustment covariates. Plots represent adjusted estimated mean over time for an adherent female patient, age 50, without comorbidities.

Abstinence syndrome also decreases over time to 12 weeks with a statistically significant effect (p<0.001). This decrease was similar by smoking level (interaction effect p=0.433), but higher in patients with FTCD≥7 (interaction effect p=0.006) and abstinence at 24 weeks (interaction effect p<0.001). Responders did not show change at 4 weeks from baseline (−0.5, CI 95%: −2.46 to 1.46, p=0.616), but at 12 weeks showed an additional decrease of 3.7 (95% CI: 1.66–5.76, p<0.001). The abstinence syndrome change over time by dependence level was similar (Fig. 3C and D).

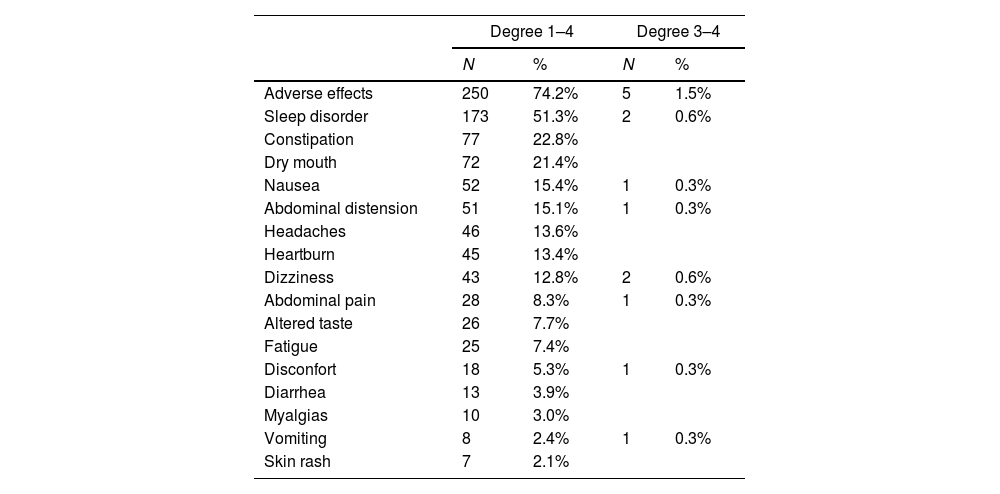

Adverse effects74% of patients presented some adverse effects investigated, but only 5 patients required treatment to control them (two patients due to sleep disorder, two patients due to dizziness, and one patient due to poor general condition and digestive symptoms). It was not necessary to withdraw medication or hospital admission due to the presence of adverse effects. Common adverse effects (occurring in more than 10% of patients) were sleep disorders, headaches, dizziness, and digestive disorders (Table 3).

Adverse effects during treatment with cytisinicline.

| Degree 1–4 | Degree 3–4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Adverse effects | 250 | 74.2% | 5 | 1.5% |

| Sleep disorder | 173 | 51.3% | 2 | 0.6% |

| Constipation | 77 | 22.8% | ||

| Dry mouth | 72 | 21.4% | ||

| Nausea | 52 | 15.4% | 1 | 0.3% |

| Abdominal distension | 51 | 15.1% | 1 | 0.3% |

| Headaches | 46 | 13.6% | ||

| Heartburn | 45 | 13.4% | ||

| Dizziness | 43 | 12.8% | 2 | 0.6% |

| Abdominal pain | 28 | 8.3% | 1 | 0.3% |

| Altered taste | 26 | 7.7% | ||

| Fatigue | 25 | 7.4% | ||

| Disconfort | 18 | 5.3% | 1 | 0.3% |

| Diarrhea | 13 | 3.9% | ||

| Myalgias | 10 | 3.0% | ||

| Vomiting | 8 | 2.4% | 1 | 0.3% |

| Skin rash | 7 | 2.1% | ||

Assessment of intensity of adverse effects:

a) Degree 1 Mild: they do not affect the patient's quality of life, do not require taking medication and it is not necessary to stop treatment.

b) Degree 2 Moderate: they affect the patient's quality of life and require taking medication.

c) Degree 3 Serious: they affect the patient's quality of life, require taking medication and force the treatment to be stopped.

d) Degree 4 Very serious: they involve hospitalization and put the patient's life at risk.

In patients who remain abstinent at the 24th week, there was a significant weight gain of 3.7kg on average (95% CI: 2.8–4.6, p<0.001). Similar to the gain obtained in patients who remain abstinent at the 52nd week (3.6kg, 95% CI: 2.1–5.1, p<0.001, Fig. 4).

DiscussionResults of the first Spanish observational, prospective, multicenter study on the effectiveness and safety of the use of cytisinicline in the short, medium, and long term are presented. A total of 337 smokers were studied. Data show that the effectiveness of cytisinicline was 68% at the end of treatment but was reduced to 48.7%, 40.9%, and 28.2% at the 3rd, 6th, and 12th months of follow-up, respectively. Adherence was good and was significantly related to the greater effectiveness of the treatment: those who used more than 80% of the medication multiplied by 2.2 their chances of remaining abstinent at six months follow-up. Furthermore, it was found that the intensity of craving, measured by SRC, at the end of pharmacological treatment was accompanied by a reduction in the chances of maintaining abstinence at six months follow-up, in such a way that for each point on the SRC at the end of pharmacological treatment, the smoker reduced the chances of maintaining abstinence at six months by 13%. Treatment tolerance data were good, and only in 5 patients was it necessary to use treatment to control adverse effects.

Abstinence rates obtained in our study are similar to those published by other authors [4,6–8,14]. It is noteworthy that approximately, between the end of pharmacological treatment and six months, abstinence rate is reduced by almost 30 points, despite the fact that during that time the clinical–psychological care protocol that we used covered up to four follow-up visits in which patients received psychological counseling of moderate intensity. This data, together with the other data we have obtained that speaks of a 13% reduction in the chances of maintaining abstinence for each point in the SRC assessment at the end of pharmacological treatment, strongly suggests the need to prolong pharmacological treatment for more than 25 days in order to control the intensity of nicotine withdrawal syndrome and to improve the effectiveness of the medication. Five studies have analyzed the effectiveness of prolonging treatment with cytisinicline for more than 25 days [7]. In all of them, the extension of treatment with cytisinicline for more than 25 days has been shown to increase effectiveness, maintaining good tolerance. The most recent study is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which two different types of treatment duration with cytisinicline (6 or 12 weeks) were compared with placebo with a follow-up of up to 24 weeks. For the 6-week treatment cycle, abstinence rates were 25.3% versus 4.4% during weeks 3–6 (odds ratio [OR], 8.0 [95% CI, 3.9–16.3]; p<.001) and 8.9% versus 2.6% during weeks 3 to 24 (OR, 3.7 [95% CI], 1.5–10.2]; p=0.002). For the 12-week course of cytisinicline, continued abstinence rates were 32.6% vs. 7.0% for weeks 9–12 (OR, 6.3 [95% CI, 3.7–11.6]; p<.001) and 21.1% vs. 4.8% for weeks 9–24 (OR, 5.3 [95% CI, 3.7–11.6]; 2.8–11.1]; p<0.001) [7].

Although 74% of the patients suffered some adverse effect, the vast majority of them were mild in intensity and self-limited over time without the need to receive any type of treatment. Probably, the high number of patients who expressed adverse effects in our study is due to the fact that throughout the follow-up visits we actively searched for them. Only in five patients was it necessary to use treatment to control adverse effects. No patient had to abandon treatment due to an adverse effect. The most frequent adverse effects were sleep disorders, headaches, dizziness, and digestive disorders. Although sleep disorders appeared in half of the patients, headaches, dizziness, and digestive disorders occurred in 13% to 15% of them. The good tolerance of cytisinicline has been shown in all the meta-analyses and in the different clinical trials carried out with this medication [3,4,6–12,14]. Regarding the safety of the use of cytisinicline, it is important to note that the latest meta-analysis indicates that, after analysing six clinical trials in which 4478 smokers participated, no significant differences were found in terms of the appearance of adverse effects between active treatment and placebo (RR=1.19, 95% CI=0.99–1.41, p=0.0624) [8]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the low affinity that cytisinicline has for 5-HT3A receptors is the reason why gastrointestinal adverse effects are mild and do not exceed 12–15% [28].

The evolution of weight gain in abstinent subjects showed that the greatest gain is obtained in the first three months of quitting. In our group, it was up to 4kg on average. And then it reduces slightly from the sixth month, remaining at the same level until the twelfth month. This evolution is similar to that found in other studies [29].

From a practical point of view, we think that the main lesson of our analysis is the importance of insisting patients adhere to treatment since those who comply with more than 80% of the prescribed dose double their chances of remaining abstinent at six months of follow-up. On the other hand, it is highly recommended that patients undergoing treatment with cytisinicline carefully assess the presence and intensity of craving throughout the treatment period, using the SRC: a progressive decrease can be interpreted as a sign of good prognosis, but it should be taken into account that the greater the intensity of the craving at the end of the treatment, the lower the chances of maintaining abstinence six months follow-up.

The first strength of our multicenter real-world data clinical study is the generalisability of results because they reflect real-life clinical scenarios, patient adherence, and treatment variations across different healthcare settings, making findings more applicable to broader patient populations. But we must mention that the group of patients who were included had to comply with the indications of the medication's technical specifications, which is why we did not include patients under 18 or over 65 years of age or patients with unstable angina, uncontrolled arrhythmias, recent myocardial infarction, uncontrolled cerebrovascular disease, patients with neuropsychiatric disorders, patients with kidney or liver failure, or patients with other drug dependencies. Pregnant or breast-feeding women were also not included.

Another habitual limitation in observational real data studies is the missing data because the patient does not attend any of the scheduled visits or there is a loss of follow-up. We have performed the analysis under a “worst-case scenario” approach, imputing missing data in response as no abstinence. This is a conservative strategy that ensures the robustness of the results and is particularly useful when analysing treatments where missing data could bias conclusions in favor of the intervention. Regarding the determination of continuous abstinence, it should be noted that all verbal statements of abstinence were verified by measuring CO levels in expired air [30].

ConclusionThis study reports the first analysis in Spain on the effectiveness and safety of cytisinicline for smoking cessation in the short, medium, and long term. Abstinence reached 68% at the end of treatment and declined to 28.2% at 12 months. Patients with adherence above 80% doubled their likelihood of success, while those with higher craving intensity at treatment completion had significantly lower abstinence rates at six months. Each one-point increase in craving intensity, measured by the SRC, reduced the probability of cessation at six months by 13%. Cytisinicline was safe, well-tolerated, and associated with high adherence and patient satisfaction. As a subgroup of patients still reported craving at the end of treatment a factor linked to reduced abstinence further studies are needed to assess the impact of extending cytisinicline therapy.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors participated in the conception, design, and data acquisition of the study.

EP-F performed the statistical analysis. AR-P, CAJ-R, EP-F, and JIG-O drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical review and are responsible for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Artificial intelligence involvementNone of the materials have been produced partially o totally with the aid of any artificial intelligence software or tool.

FundingThis study has received funding from a SEPAR grant (Proy. n° 797).

Conflict of interest1. Angela Ramos-Pinedo: AR-P has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Aflofarm, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, FAES, Gebro, Neuraxpharm, Pfizer and Zambon.

2. Jose Ignacio de Granda-Orive: JIG-O has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Adamed, Aflofarm, Boehringer, Gebro, Neuroxpharm and Pfizer.

3. Maria Isabel Cristóbal-Fernández: MIC-F has received honoraria for lecturing, participation in clinical studies, participation in meetings and/or receiving scholarships to attend scientific congresses, for the following (alphabetical order) Adamed, Aflofarm, GSK Neuraxpharm and Pfizer.

4. Calos Rábade-Castedo: CR-C has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies for the following: Adamed, Aflofarm, Chiesi, GSK, Kenvue, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer y Teva.

5. Elia Pérez-Fernández: EP-F declares that she has no conflict of interest that could be considered to directly or indirectly influence the content of the manuscript.

6. Paz Vaquero-Lozano: PV-L declares conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry for having conducted studies, presentations, scientific advice, participating in meetings and/or receiving scholarships to attend scientific congresses with companies Aflofarm, Adamed, AstraZeneca, Bial, Chiesi y Johnson & Johnson.

7. Maria Inmaculada Gorordo-Unzueta: MIG-U PV-L declares conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry for having conducted studies, presentations, scientific advice, participating in meetings and/or receiving scholarships to attend scientific congresses with companies Aflofarm, Menarini, GSK, Pfizer, Gebro, Boeringer Ingelheim.

8. Lourdes Lázaro-Asegurado: LL-A has received honoraria for scientific collaborations and grants to attend scientific conferences from Adamed, Aflofarm, GSK, Pfizer y Neuraxpharm Spain SL.

9. Eva De Higes-Martínez: EH-M has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Aflofarm, AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Esteve, FAES, Gebro, GSK, Menarini, Neuraxpharm, Novartis, Pfizer, Rovi, TEVA and Zambon.

10. Juan Antonio Riesco-Miranda: JAR-M reports grants and personal fees from Aflofarm, Adamet, GSK, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Pfizer, Novartis AG, Menarini, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees and non-financial from Astra-Zeneca, Grants and personal fees from Gebro, personal fees from Sanofi-Regeneron, outside the submitted work.

11. Rosa Mirambeaux-Villalona: RM-V has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Aflofarm, GSK, Adamed, and Astra-Zeneca.

12. Gloria Francisco-Corral: GF-C declares conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry for having carried out studies, presentations, scientific advice, participating in meetings and/or receiving scholarships to attend scientific congresses with companies: Aflofarm, Adamed, Chiesi, GSK.

13. Alejandro Frino-García: AF-G declares conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry for having carried out studies, presentations, scientific advice, participating in meetings and/or receiving scholarships to attend scientific congresses, with the companies Aflofarm, Adamed, Chiesi, Menarini, GSK, Pfizer, Phoenix Argentina, Boeringer Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca.

14. Jaime Signes-Costa Miñana: JS-C has served as a consultant and received speaking fees at advisory boards for Aflofarm, AZ, BI, and received institutional funding for trials and research from BI, GSK and received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Aflofarm, BI, Faes, Menarini, Teva.

15. Cristina Villar-Laguna: CV-L declares that she has no conflict of interest that could be considered to directly or indirectly influence the content of the manuscript.

16. Ana Maria Cicero-Guerrero: AMC-G He declares that she has no conflict of interest that could be considered to directly or indirectly influence the content of the manuscript.

17. Julio César Vargas-Espinal: JCV-E declares conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry for having conducted studies, presentations, scientific advice, participating in meetings and/or receiving scholarships to attend scientific congresses with companies: Aflofarm, Adamed, Astra, Bial, Chiesi, Faes, Gebro y GSK.

18. Teresa Peña-Miguel: TP-M has received honoraria for scientific collaborations and grants to attend scientific conferences from Adamed, Aflofarm, GSK, Pfizer and Neuraxpharm Spain SL

19. Sellares J: JS declares conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry for having conducted studies, presentations, scientific advice, participating in meetings and/or receiving scholarships to attend scientific congresses with companies: Aflofarm, Adamed, Chiesi, GSK, Pfizer, Boeringer Ingelheim, Astra Zéneca.

20. Jiménez-Ruiz CA: CAJ-R has received honoraria for presentations, participation in clinical studies and consultancy from: Adamed, Aflofarm, Bial, GEBRO Pharma, GSK, Kenvue, Menarini, Neuraxpharm and Pfizer.