The introduction of molecular techniques has enabled better understanding of the etiology of respiratory tract infections in children. The objective of the study was to analyze viral coinfection and its relationship to clinical severity.

MethodsHospitalized pediatric patients with a clinical diagnosis of respiratory infection were studied during the period between 2009 and 2010. Clinical and epidemiological data, duration of hospitalization, need for oxygen therapy, bacterial coinfection and need for mechanical ventilation were collected. Etiology was studied by multiplex PCR and low-density microarrays for 19 viruses.

ResultsA total of 385 patients were positive, 44.94% under 12 months. The most frequently detected viruses were RSV-B: 139, rhinovirus: 114, RSV-A: 111, influenza A H1N1-2009: 93 and bocavirus: 77. Coinfection was detected in 61.81%, 36.36% with two viruses, 16.10% and 9.35% with three to four or more. Coinfection was higher in 2009 with 69.79 vs 53.88% in 2010. Rhinovirus/RSV-B on 10 times and RSV-A/RSV-B on five times were the most detected coinfections. Hospitalization decreased with greater number of viruses (P<.001). Oxygen therapy was required by 26.75% (one virus was detected in 55.34% of cases). A larger number of viruses resulted in less need for oxygen (P<.001). Ten cases required mechanical ventilation, four patients with bacterial coinfection and five with viral coinfection (P=.69).

ConclusionsAn inverse relationship was found between the number of viruses detected in nasopharyngeal aspirate, the need for oxygen therapy and hospitalization days. More epidemiological studies and improved quantitative detection techniques are needed to define the role of viral coinfections in respiratory disease and its correlation with the clinical severity.

Las técnicas moleculares han permitido un mejor conocimiento de la etiología de las infecciones respiratorias infantiles. El objetivo del estudio fue analizar la coinfección viral y su relación con la gravedad clínica.

MétodosSe estudió a pacientes pediátricos hospitalizados con diagnóstico clínico de infección respiratoria durante el periodo comprendido entre 2009 y 2010. Se recogieron datos clínicos, epidemiológicos, duración de la hospitalización, necesidad de oxigenoterapia, coinfección bacteriana y necesidad de ventilación mecánica. Etiología estudiada con técnica PCR múltiple y microarrays de baja densidad para 19 virus.

ResultadosUn total de 385 pacientes presentaron resultados positivos, 44,94% menores de 12 meses. Los virus más detectados fueron: VRS-B: 139, rhinovirus: 114, VRS-A: 111, influenza A H1N1-2009: 93 y bocavirus: 77. Se detectó coinfección en el 61,81%, un 36,36% con 2 virus, 16,10% con 3 y 9,35% con 4 o más. La coinfección fue superior en 2009 con 69,79 frente 53,88% en 2010. Rhinovirus/VRS-B en 10 ocasiones y VRS-A/VRS-B en 5 fueron las coinfecciones más detectadas. Menor hospitalización a mayor número de virus detectados (p < 0,001). Necesitaron oxigenoterapia el 26,75% (en 55,34% se aisló un virus), objetivando a mayor número de virus menor necesidad de oxígeno (p < 0,001). Precisaron ventilación mecánica 9 casos, 4 de ellos con coinfección bacteriana y 5 con coinfección vírica (p = 0,69).

ConclusionesObjetivamos una relación inversamente proporcional entre número de virus detectados en aspirado nasofaríngeo, necesidad de oxigenoterapia y días de hospitalización. Se necesitan más estudios epidemiológicos y mejoría en las técnicas de detección cuantitativa para definir el papel de las coinfecciones víricas en la enfermedad respiratoria y su correlación con la gravedad clínica.

Respiratory viral infection is a major source of morbidity and mortality in childhood. Just over one-third of preschool-aged children develop lower respiratory infections during their first year of life. Between 1% of 2% of these patients require admission to hospital.1,2

The etiological agent is not always identified in these patients. Children with respiratory infections are generally treated as outpatients and the etiology of their disease is not investigated. If they are hospitalized, the commonly employed evaluation techniques are often not sufficiently sensitive.3

Experience and understanding of the role of viral coinfections in respiratory infections has grown in recent years, thanks to the introduction of molecular techniques.4–6 At present, the clinical data available on coinfection, in terms of both the number of viruses involved and the severity of the condition, are variable and even, at times, contradictory. These discrepancies may be due to factors that affect the various etiological agents, such as geographical region and methods of detection employed.

The aim of this study was to analyze the viral etiology of respiratory infections and the real clinical implications of coinfection, and its possible relationship to clinical severity in a population of hospitalized patients in a general hospital located in Barcelona with a secondary-level pediatric department. Etiology was determined using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and low density microarrays.

Patients, Materials and MethodsPatientsPediatric patients, aged between 7 days and 15 years, hospitalized for respiratory infections were included in a prospective study conducted from February 1, 2009 until December 31, 2010 in the Pediatric Department of Hospital de Mar, Barcelona. The basic inclusion criterion was an initial diagnosis of (a) respiratory tract infection (rhinopharyngitis, laryngitis, bronchitis or pneumonia), with clinical signs suggesting viral infection; (b) influenza-like syndrome; (c) suspected pertussis; or (d) pneumonia with clinical signs suggesting bacterial infection or empyema, poor progress during admission and suspected viral coinfection.

Personal and epidemiological data were collected together with the reason for admission and clinical progress, duration of hospitalization, oxygen requirements in cases with O2 saturations ≤92%, and need for admission to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) for mechanical ventilation were recorded.

Cases were stratified by age groups (younger than 12 months, between 1 and 3 years, between 3 and 5 years and older than 5 years), and probable diagnosis at time of admission, days of hospitalization (pooled as less than 4 days, between 5 and 10 days and longer than 10 days), need for oxygen therapy, need for transfer to PICU for mechanical ventilation, number of viruses detected and presence of bacterial coinfection were recorded.

Samples for Virological StudyNasopharygeal aspirate was collected from all patients during the first 12h of admission. In patients with clinical suspicion of bacterial pneumonia, a nasopharyngeal aspirate specimen was also obtained at any time when poor progress was suspected to be due to viral or bacterial coinfection and not to a poor response to treatment or virulence of the primary etiological agent. Laboratory tests were performed on the same day that the specimen was obtained, except at weekends. Samples were stored at 2–8°C until analysis.

Extraction of Nucleic AcidsNucleic acid (RNA/DNA) extraction was performed using MagnaPure LC, Roche Diagnostics.

Amplification and DetectionThe CLART®PneumoVi kit from Laboratorios Genómica, Madrid, Spain was used. This method can detect and characterize the 19 most common types and subtypes of human viruses causing respiratory infections, including: adenovirus; bocavirus; coronavirus; enterovirus (echovirus); influenza virus A (human H3N2, human H1N1, B, C and H1N1/2009 subtypes); metapneumovirus (A and B subtypes); parainfluenza virus 1, 2, 3 and 4 (A and B subtypes); rhinovirus; respiratory syncytial virus type A (RSV-A); respiratory syncytial virus type B (RSV-B).

Viruses were detected using a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique after reverse transcription of viral RNA (RT-PCR) for amplification of a specific 120–330 base-pair fragment of the viral genome. The amplified product was visualized using the low-density microarray-based technological platform, CLART® (Clinical Array Technology).

Each amplification tube had an internal control to monitor amplification.

In 2009, detection of the influenza A virus H1N1/2009 was not included in the system, but was added in 2010. Until this time, identification was performed using real-time PCR (RT-PCR) that detected the M2 and HA1 genes, using the kit marketed by Roche.

Statistical AnalysisData were stored in an Excel-supported database and the statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. First, a univariate descriptive analysis was performed. Qualitative data were presented by the frequency distribution of percentages in each category. In the analytical statistics phase, the number of viruses detected was analyzed to determine any relationship with days of hospitalization, age and need for oxygen therapy. The association between these factors was investigated using hypothesis testing methods, and proportions were compared using the Pearson's Chi-squared test. Results with P-value <.05 were considered significant.

ResultsSamples from 463 pediatric patients admitted to the Pediatrics Department of the Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, for community-acquired respiratory infections were analyzed. Results were positive in 385 (83.15%) samples. Age distribution was as follows: younger than 12 months, 173 (44.94%), from 12 months to 3 years, 143 (37.14%), from 3 to 5 years, 53 (13.77%) and older than 5 years, 16 (4.15%); 44.94% of the cases were under the age of 12. None of the patients had risk factors for respiratory diseases. Clinical diagnoses of the positive patients were as follows: 100 cases of bronchiolitis, 92 pneumonia, 81 bronchitis, 80 upper respiratory tract infection, 25 influenza-like syndromes, six pertussis and one newborn with risk of infection (Table 1).

Relationship Between Number of Viruses Detected and Diagnoses.

| Diagnosis | Number of viruses detected | Total | ||

| 1 virus | 2 viruses | ≥3 viruses | ||

| Bronchiolitis | 50 | 41 | 9 | 100 |

| Pneumonia | 29 | 36 | 27 | 92 |

| Bronchitis | 24 | 32 | 25 | 81 |

| URTI | 32 | 23 | 25 | 80 |

| Flu-like syndrome | 5 | 8 | 12 | 25 |

| Pertussis | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Neonatal risk of infection | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 147 | 140 | 98 | 385 |

URTI: upper respiratory tract infection.

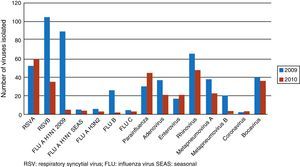

Viruses detected are shown in Fig. 1. The five most common viruses in both study periods were RSV-B (139 cases), rhinovirus (114), RSV-A (111), influenza virus serotype A H1N1/2009 (93) and bocavirus (77). The percentages of codetections in each period were: (a) in 2009, 69.79% of infections were caused by more than 1 viral agent (134 of 192 infections detected); (b) in 2010, the proportion was 53.88% (104 of 193 infections detected). The most common coinfections were rhinovirus+RSV-B in 10 cases and RSV-A+RSV-B in 5.

Coinfection was found in 61.81% of samples from positive patients. Of these, two viruses were found in 36.36%, three viruses in 16.10% and four or more viruses in 9.35%.

We found a shorter hospital stay in patients with a greater number of viruses (P<.001), as reflected in Table 2; the association was linear.

Correlation Between Hospital Stay and Detection of Respiratory Viruses.

| Hospital stay (days) | Number of viruses detected | Total cases by hospital stay (%) | ||

| 1 virus | 2 viruses | ≥3 viruses | ||

| 1–4 | 67 | 76 | 77 | 220 (57.1) |

| 5–10 | 67 | 53 | 10 | 130 (33.8) |

| >10 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 35 (9.1) |

| Total cases with number of viruses detected (%) | 147 (38.2) | 140 (36.4) | 98 (25.5) | 385 (100) |

P<.001.

The 103 patients who required oxygen therapy (basal saturations≤92%) are described in Table 3. When these data were correlated, it was revealed that the younger the patient, the more frequent the need for oxygen therapy, a trend that was statistically significant (P<.001), and the greater the number of viruses detected the less need for oxygen therapy (P<.001).

Correlation Between Age and Number of Viruses Detected in Patients Requiring Oxygen Therapy.

| Age | Number of viruses detected | Total | ||

| 1 virus | 2 viruses | ≥3 viruses | No. (%) | |

| <12m | 42 | 22 | 10 | 74 (71.84) |

| 1–3y | 13 | 7 | 3 | 23 (22.33) |

| >3–5y | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 (4.85) |

| >5y | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.98) |

| Total n (%) | 57 (55.34) | 32 (31.07) | 14 (13.59) | 103 |

m: months; y: years.

P<.001.

Admission to the PICU for mechanical ventilation was required in nine cases. Age, clinical presentation, viruses detected and diagnosis are shown in Table 4. The predominant etiological agent in these patients was RSV. No statistically significant differences were found when viral coinfection was correlated with the need for mechanical ventilation in the PICU (P=.69).

Characteristics of Patients Admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

| Age | Sex | Diagnosis | Type of infection |

| 21 days | Male | Bronchiolitis/pneumonia | RSV-A+enterovirus+adenovirus+suspected bacterial coinfection |

| 25 days | Male | Bronchiolitis/atelectasis | RSV-B |

| 1 month | Female | Bronchiolitis | RSV-A |

| 2 months | Female | Bronchiolitis | RSV-B |

| 3 months | Female | Bronchiolitis | RSV-A+influenza B+adenovirus |

| 3 months | Male | Bronchiolitis | Adenovirus |

| 9 months | Male | Bronchitis | Rhinovirus+bocavirus |

| 20 months | Female | Empyema | RSV-B+influenza BS. pneumoniae |

| 4 years | Male | Empyema | RSV-A+H1N1-2009S. pneumoniae |

A clinical suspicion of bacterial coinfection based on the patients’ clinical picture and acute phase reactant values was determined in 37 cases (8.50%). However, this was confirmed in only two cases, in which Streptococcus pneumoniae was confirmed in a positive blood culture or PCR. One virus was detected in 20 cases and two viruses in 14 cases. Hospital stay for 27 patients was between 1 and 4 days and between 5 and 10 days for 10 patients. In the eight cases with a diagnosis of atypical pneumonia on serology, viral coinfection with a single virus was detected in 5.

DiscussionThe first finding of significance is the high rate of positive results in the population without risk factors (83.15% of samples studied) and the high rate of coinfection (61.81%), particularly in the first year of the study (69.79%). In the literature, coinfection rates range from 8% to 76%, depending on the series.7–16 With regard to the severity of our cases, it is important to note that a greater number of viruses is not synonymous with greater severity. According to our results, the number of viruses detected is in inverse proportion to the need for oxygen therapy and days of hospital admission; this relationship was statistically significantly (P<.001). However, of the nine cases admitted to the PICU, more presented coinfection, but this was not statistically significant.

Some studies have reported no clinical differences between patients with respiratory infections caused by a single agent and those caused by multiple viruses detected in nasopharyngeal aspirates from hospitalized children.8,11,13,17–23 Of interest is the study performed by Camargo22 in Sao Paulo during the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, in which 21.9% of cases had coinfection not associated with greater morbidity or mortality. In contrast, other studies show that coinfection is a risk factor for poor progress.14,23–28 One of the most important of these was performed in Vienna by Aberle et al.,14 between 2000 and 2004. They reported that airway obstruction was more severe when RSV contributed to the coinfection, and mean hospital stay lengthened if rhinovirus was involved. In another study, Grensill et al.26 showed that when the coinfection consisted of RSV and metapneumovirus, progress was poorer. Furthermore, Richard et al.,28 who studied the relationship of coinfection with need for PICU admission, concluded that the presence of two or more viruses increased the likelihood of PICU admission 2.7-fold. However, in another study conducted in patients admitted to the PICU, Ghani et al.29 found that only bacterial confection was associated with a longer hospital stay, with no increase in mortality.

We should also remember that the detection of more than one virus may be due to the presence of viral fragments persisting for up to 5–6 weeks after onset of symptoms,14 which may not have any real role in the pathogenicity of the clinical process.30 Relationships may be established with the help of epidemiological techniques, but the use of quantitative techniques would be much more useful for interpreting the contradictions produced by attributing greater or lesser severity to coinfections.

One important limitation of this study of the role of coinfection in upper respiratory tract infections is the small number of cases evaluated, compared to the high number seen in normal pediatric practice. The vast majority of cases do not need hospitalization, and this limits our knowledge of the real situation and prevents us from extrapolating our data to the general population. One final issue that remains unclear is the long-term effect that these coinfections may have on the respiratory system and the development of chronic lung disease.

ConclusionsAlthough an inverse relationship was found between the number of viruses detected in nasopharyngeal aspirate, the need for oxygen therapy and hospital stay, the results of our study differ widely from the data published by other groups. More epidemiological studies and improved quantitative detection techniques are needed to define the role of viral coinfections in respiratory disease and how they correlate with clinical severity.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Roig A, Salvadó M, Caballero-Rabasco MA, Sánchez-Buenavida A, López-Segura N, Bonet-Alcaina M. Coinfección vírica en las infecciones respiratorias infantiles. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:5–9.