An alveolopleural fistula (APF) represents an abnormal communication between alveoli and pleural space. In most patients these fistulas spontaneously resolve 1. If air leak persists beyond 5–7 days, it is considered an APF with prolonged air leak 2. As a novel approach, we describe a technique in which a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) was used to localize a fistula with prolonged air leak – as an alternative to existing devices.

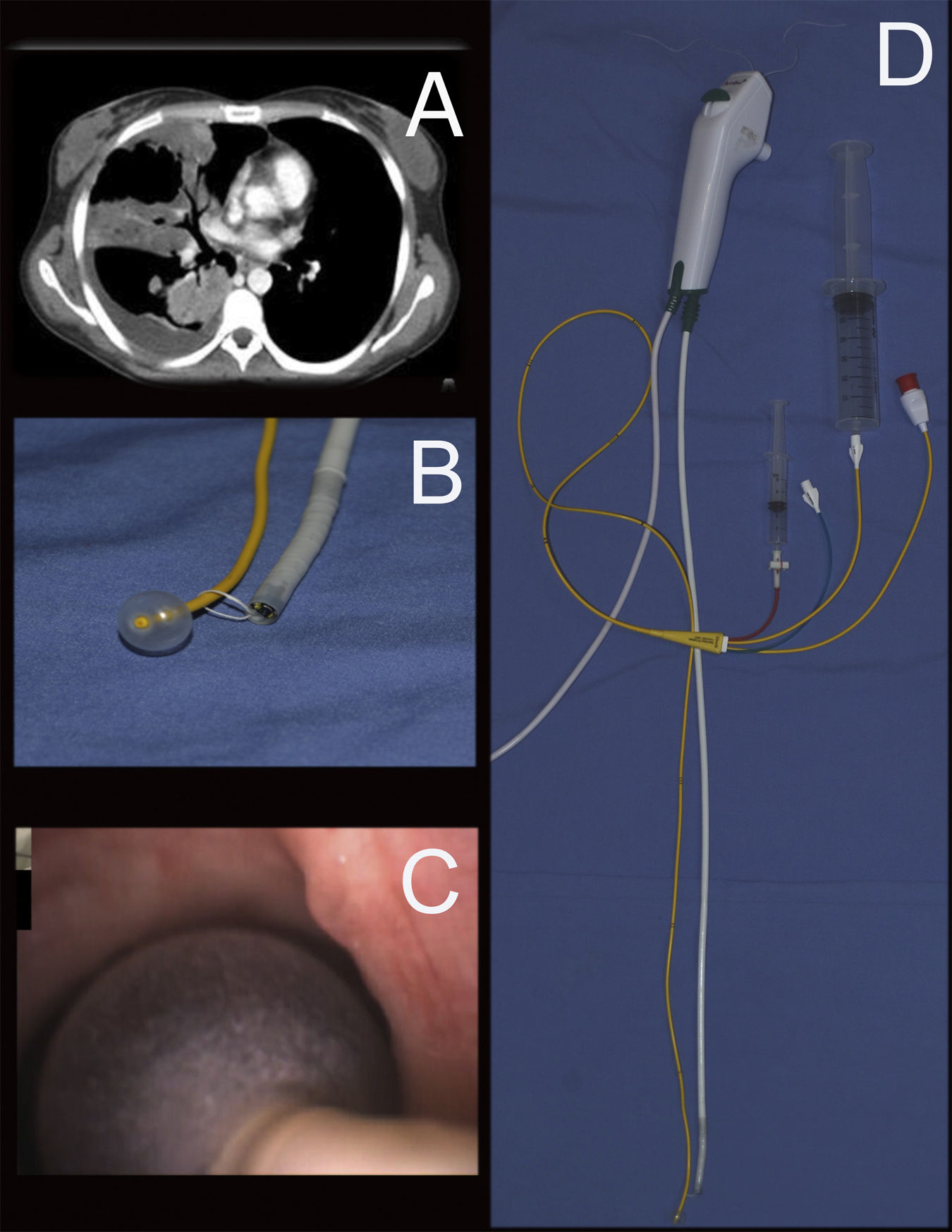

Case presentation: A 33-year-old immunosuppressed woman with a history of autoimmune hepatitis was admitted with a lung abscess and pleural effusion. Despite antibiotic treatment, the patient progressed to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (MV). A chest CT scan demonstrated multiple right lung cavitary lesions and pleural effusion (Fig. 1A). A diagnostic/therapeutic thoracentesis was performed, and purulent fluid was obtained, prompting chest tube insertion. Shortly after successful chest tube placement, a persistent air leak was observed (Grade 4C). This air leak persisted in time, despite attempts to minimize tidal volumes and PEEP. After seven days, the air leak continued so a decision was made to find the exact location of the fistula.

This procedure was performed in the intensive care unit as the patient was being mechanically ventilated. A regular single-use bronchoscope (2.0mm working channel, Ambu aScope) and a 7 Fr pulmonary artery catheter (Swan Ganz – Edwards Lifesciences) were used. A 3-0 suture was used to ensnare the bronchoscope to the PAC (Fig. 1B). To support ventilation during the diagnostic/therapeutic bronchoscopy procedure, we used an 8.5mm orotracheal ET tube with an elbow shaped adapter to allow for access. No signs of bronchial fistula were found in central airways or in proximal lobar segments. Then, the PAC was advanced inserted into each lobar bronchus and the balloon was inflated with 2ml of air, confirming complete bronchial occlusion and preventing air from entering the evaluated lobe. We allowed for 2min with balloon inflated in each lobe (RUL, then RML, then RLL sequentially) while monitoring for any change in air leak pattern in the drainage system for each potential area of concern (Fig. 1C). As the balloon was inflated at the middle lobe bronchus (RB4+RB5), the air leak slowed down to eventually stop. To further confirm these findings, 60ml of air were jetted distally – using one of the distal PAC ports (Fig. 1D). This maneuver resulted in air leak visualization at the chamber. As the balloon was deflated then air leak was observed again and persisted in time. No changes in leak volume were observed when occluding other lobar bronchi. The procedure was concluded in satisfactory fashion after successful identification of the affected area. The case was discussed in a multidisciplinary forum. Various therapeutic approaches had been considered, although given refractory hypoxemia within 48h of bronchoscopy, and rapid clinical decline due to sepsis the patient was not deemed candidate for any treatment modality and expired on at hospital day 15.

The most frequent causes for APF with prolonged air leak include lung volume reduction surgery, pulmonary resections, and bronchoscopic biopsies 1–3. Less frequent etiologies include necrotizing pneumonia, pleural drainage procedures and barotrauma due to mechanical ventilation 4. The mortality rate for mechanically ventilated patients among those with prolonged air leak ranges from 25% to 81% 5.

There is no current consensus regarding best approaches to diagnose and address APFs. Conventional treatment mandates pleural space drainage with or without wall suction, general supportive care and treatment of other underlying conditions 6.

If the patient requires MV support, airway pressure should be minimized in order to reduce shear forces at the fistula. This can be achieved by reducing the respiratory rate, tidal volume and the positive expiratory pressure. Anecdotally, high frequency oscillatory ventilation has been used among this patient population 7.

If these measures fail, then surgical and endoscopic options are to be considered. Importantly, the presence of collateral ventilation plays a role in deciding best approach. Other factors to consider include local equipment availability, proceduralists expertise, and expected outcomes. Of note, it is paramount to attempt fistula localization by sequential segmental/lobar balloon occlusion.

Endoscopic intervention with endobronchial valves, silicone spigots, occlusion materials/glues or bronchial stent placement have shown some efficacy in situations where collateral ventilation is minimal and there is significant leak reduction during the bronchial occlusion test 8.

A technique to localize the fistula using a bronchial occlusion balloon has been previously described. Fogarty balloons have been used in the past. Other alternatives to localize a fistula include oxygen insufflation with an endoscope placed in the airways and observation of its effect on the leak in the water seal 9. Alternatively, instillation of methylene blue in the pleural cavity through the drain tube and the posterior endoscopic detection of the stained tissue may be considered.

Previous work demonstrated the safety and usefulness of PAC catheter use for bronchoscopy management of massive haemoptysis or glues instillation 10,11. We hereby describe the off label use the device and the first case report on the use of PAC to localize an alveolopleural fistula.

Unlike bronchial occlusion balloons, these PAC are readily available devices in most institutions, with a distal access port that enables air insufflation. Some advantages over other commercial available devices include cost, multiple ports for instillation, and widespread availability. In particular other commercially available devices may have disadvantages over the PAC: 1) fogarty occlusion balloons have no distal port (for air insufflation), CRE balloons may exert unwanted radial stress on bronchial walls, and other commercially available products may not be readily available in hospitals without advanced bronchoscopic service lines.

In conclusion, a PAC is an easy to use, convenient, readily available, financially viable tool that is likely useful for the localization and isolation of an alveolo-pleural fistula using the occlusion method and which allows the confirmation of the localization by syringe insufflation.

FundingWe don’t receive funding for this work from any of the following organizations: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Wellcome Trust; Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI); and other(s).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We are grateful to Daniel Buljubasich for assistance in editing this manuscript.