Pneumomediastinum (PM) and subcutaneous emphysema (SE) are generally benign entities with a self-limiting course. There is a potential risk for complications due to massive accumulation of air that could compromise the life of the patient by interfering with respiratory mechanics and complicating venous return. In these cases, a less aggressive and effective therapeutic option is the use of subcutaneous drains. We present the case of a 75-year-old male with PM and massive SE that was resolved with this type of drains.

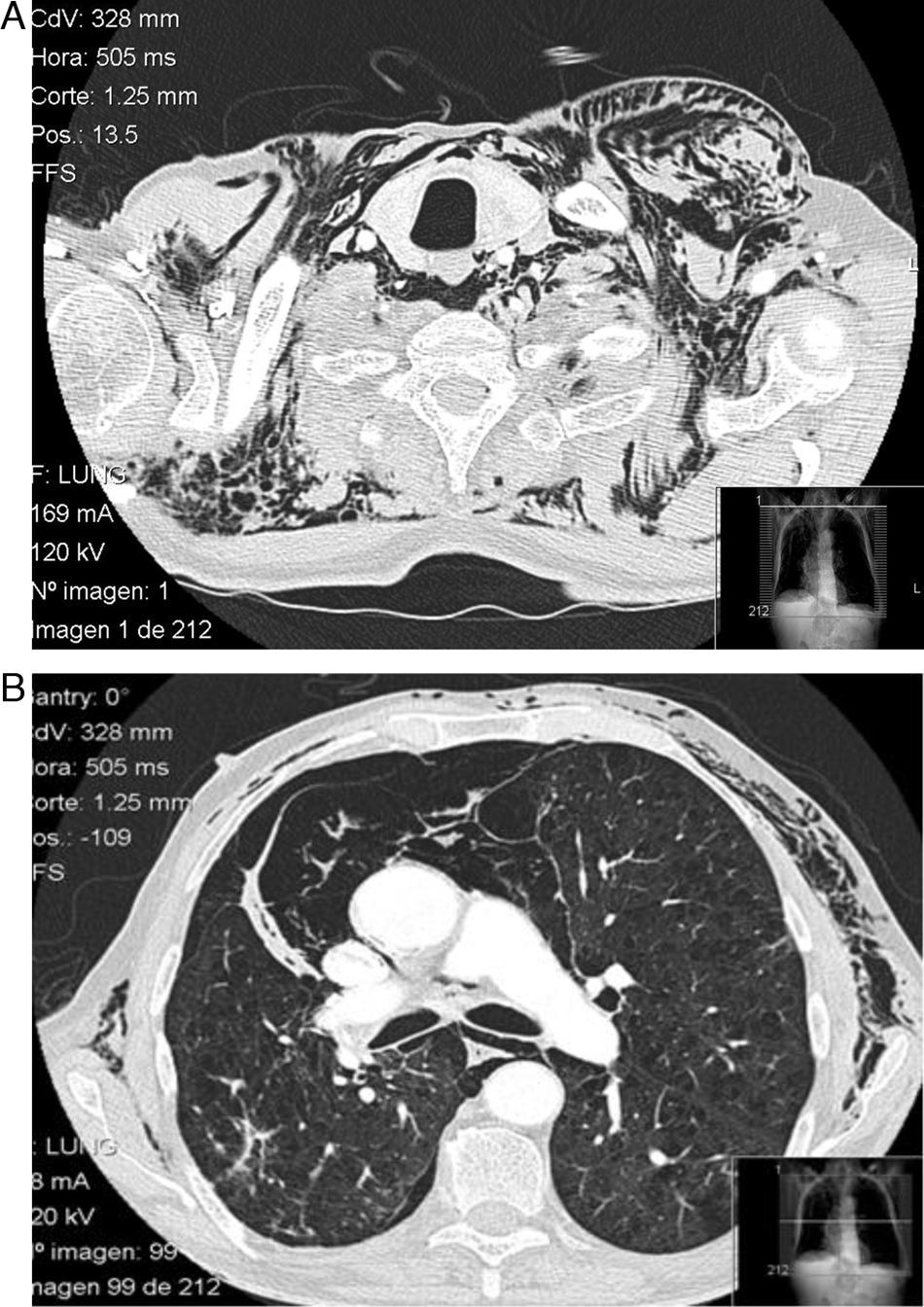

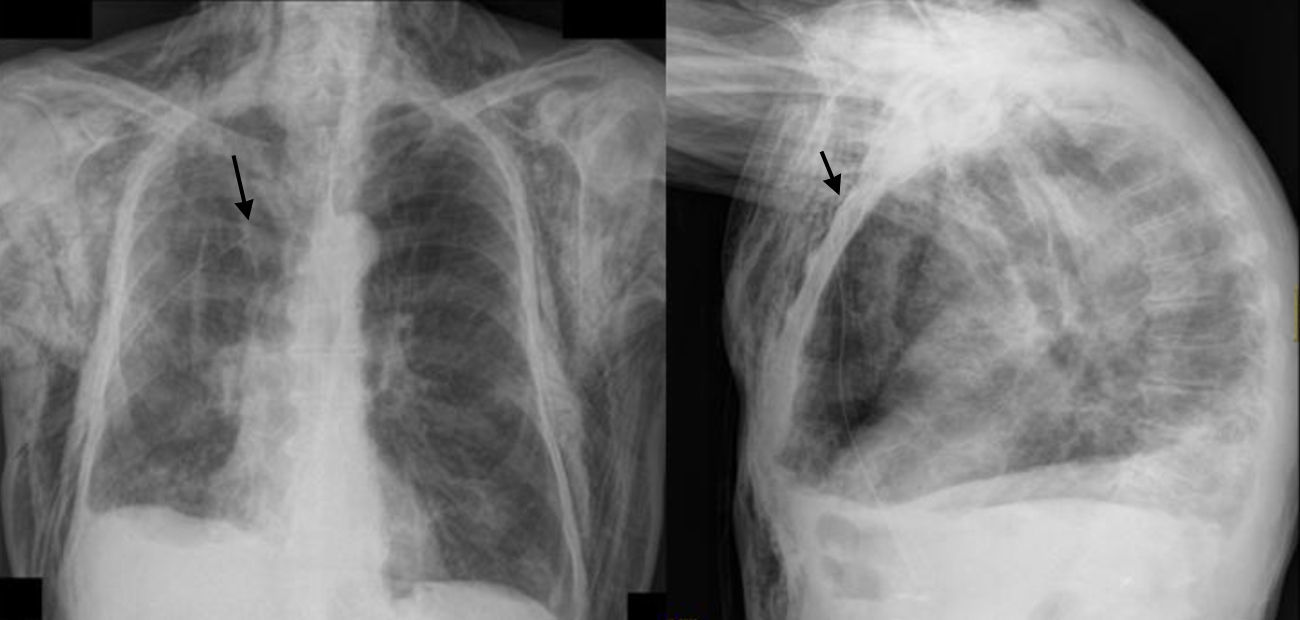

A 75-year-old male with GOLD grade IV COPD, who had undergone upper right lobectomy for pulmonary epidermoid carcinoma, came to our emergency room due to COPD exacerbation. The patient was admitted to hospital and evolved favorably during the first 72h. On the fourth day of hospitalization, after the exertion of defecating, he presented dyspnea and left pleuritic chest pain. Upon examination, subcutaneous emphysema was found in the apical region of the left hemithorax. Chest radiography confirmed the presence of air in the subcutaneous tissue. The patient was treated with rest, oxygen therapy and analgesia, but the subcutaneous emphysema extended throughout the thorax, face, eyelids and abdomen. Thoracic CT showed the presence of PM and massive SE with no evidence of pneumothorax, pulmonary emphysema and post-surgical absence of the left upper pulmonary lobe (Fig. 1). After 48h, the patient presented symptoms of thoracic discomfort, sweating and presyncope, and electrocardiogram demonstrated paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. In this situation, it was decided to insert a right subcutaneous drain (Fig. 2). The patient's symptoms improved almost immediately, and the drain was able to be withdrawn 5 days later. Over the following 6 months, the patient presented no relapse.

PM and SE are usually caused by a iatrogenic or traumatic trigger, although on occasion they may be secondary to an abrupt increase in intra-alveolar pressure, which is a phenomenon known as the Macklin effect.1 The incidence of PM is low although underdiagnosed because its symptoms are non-specific and the radiological signs are difficult to identify. Typical symptoms at onset include chest pain, dyspnea and subcutaneous emphysema, and occasionally cervical pain, odynophagia, dysphagia, dysphonia and pulsus paradoxus. Hamman's sign only appears in 12% of cases.2 Diagnosis is confirmed on chest radiograph by the presence of air separating mediastinal structures or surrounding them and subcutaneous emphysema, while less frequent signs may also be identified, such as the spinnaker-sail sign, pneumopericardium, etc.3 The differential diagnosis includes acute coronary syndrome, pericarditis, pneumothorax, pulmonary thromboembolism, rupture of the tracheobronchial tree and Boerhaave syndrome. In most cases, there is complete resolution of the symptoms within 4 days. Nevertheless, there are cases that may involve compression of pulmonary or mediastinal veins, which simulates cardiac tamponade. These cases, which Macklin calls “malignant pneumomediastinum”,4 require fast action that should be directed at immediately evacuating the air accumulated in the mediastinum. Massive accumulation of air in the subcutaneous tissue can also compromise the life of the patient due to pneumatic compression of the thorax, causing progressive hypoxemia and hypercapnia. The use of subcutaneous drains can be very useful in these cases; they are effective almost immediately and can be withdrawn in a few days. In selecting the type of drain, one must take into account their availability and the training of the staff for their insertion. Another important factor is the characteristics of each type of catheter, as smaller-caliber tubes are more comfortable but entail a greater risk of obstruction, and wider tubes are permeable for a longer period of time but can cause patient discomfort.5

Please cite this article as: Santalla Martínez M, et al. Tratamiento con drenajes subcutáneos en el neumomediastino y enfisema subcutáneo masivo. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49:127-8.