Tuberculosis (TB) is still a major worldwide public health problem. Individuals with latent tuberculosis infection (LTI) are at risk of developing the disease, and this risk is associated with their immune status. The development of TB can be avoided by the use of preventive treatment - treatment of latent tuberculosis infection or TLTI.1 The effectiveness of TLTI depends on the efficacy of the regimens used2 and on compliance with these regimens.3

We conducted an observational retrospective study to evaluate TLTI compliance and factors associated with dropout.

Subjects with a diagnosis of LTI who began TLTI in the Unidad Clínica de Tuberculosis Vall d’Hebron-Drassanes between January 2011 and December 2016 were studied. The diagnosis of LTI was established on the basis of a positive tuberculin test and/or IGRA with a normal chest X-ray. The TLTI regimen was indicated according to the guidelines of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery.4

All cases were followed up with monthly clinical and laboratory evaluations, and whenever the patient presented intolerance. Adherence was assessed through interview and determination of isoniazid metabolites in urine,5 and compliance was defined as administration of more than 80% of the prescribed doses.

In total, 1113 patients with a mean age of 29 years were included consecutively; 713 were men (64%). A total of 793 (71%) were immigrants from more than 50 countries (Table 1). Seventy percent of African patients were from the Maghreb countries (primarily Morocco), and the rest were sub-Saharan. In total, 71.5% of Asians were from the Indian subcontinent, the majority from Pakistan. In the group of Latin American patients, most were from Bolivia (23%), Ecuador (21%), Peru (14%), Dominican Republic (11%), and Colombia (9%). Fifty-five percent of patients from eastern Europe were Romanian.

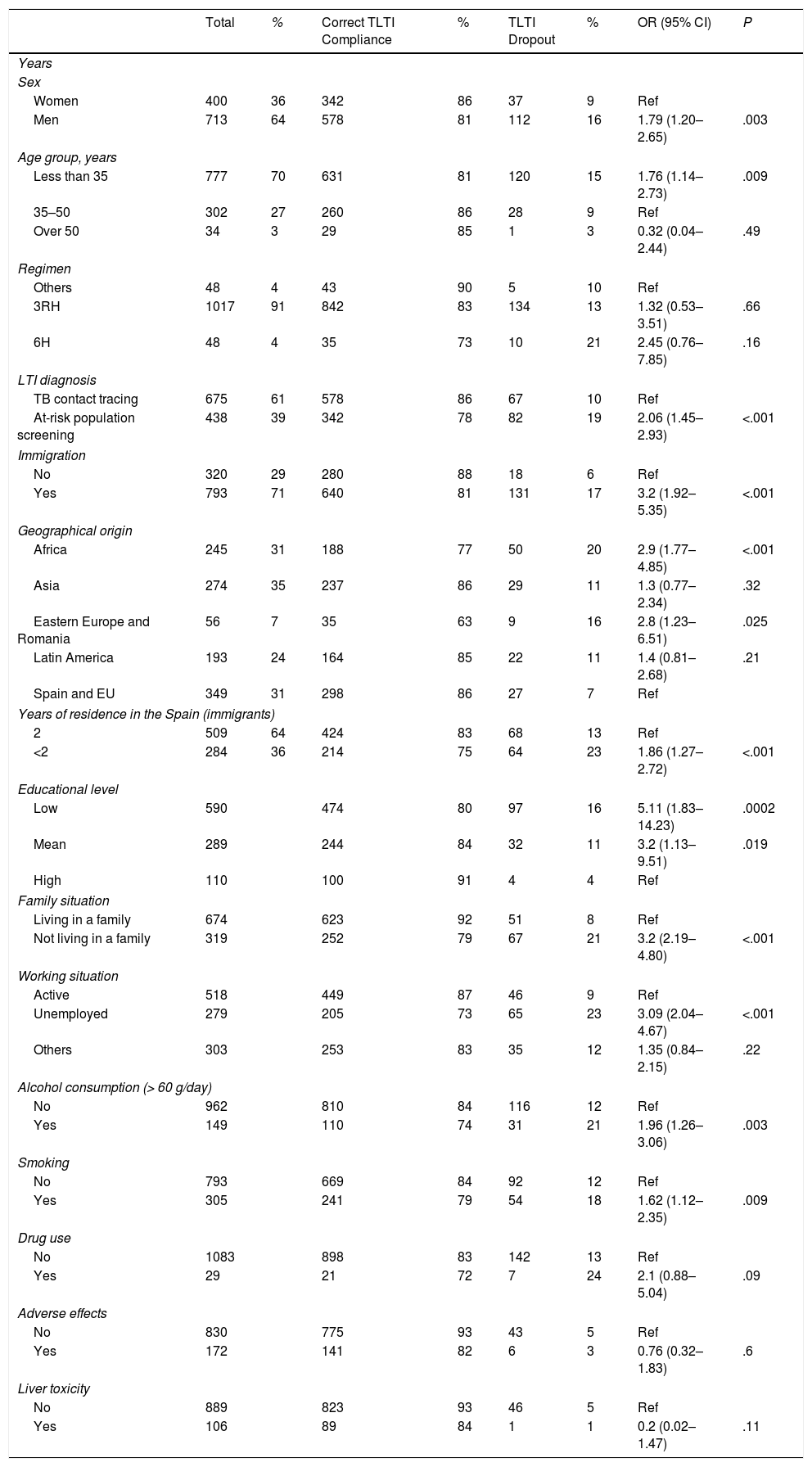

Factors Associated with Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Compliance.

| Total | % | Correct TLTI Compliance | % | TLTI Dropout | % | OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Women | 400 | 36 | 342 | 86 | 37 | 9 | Ref | |

| Men | 713 | 64 | 578 | 81 | 112 | 16 | 1.79 (1.20–2.65) | .003 |

| Age group, years | ||||||||

| Less than 35 | 777 | 70 | 631 | 81 | 120 | 15 | 1.76 (1.14–2.73) | .009 |

| 35–50 | 302 | 27 | 260 | 86 | 28 | 9 | Ref | |

| Over 50 | 34 | 3 | 29 | 85 | 1 | 3 | 0.32 (0.04–2.44) | .49 |

| Regimen | ||||||||

| Others | 48 | 4 | 43 | 90 | 5 | 10 | Ref | |

| 3RH | 1017 | 91 | 842 | 83 | 134 | 13 | 1.32 (0.53–3.51) | .66 |

| 6H | 48 | 4 | 35 | 73 | 10 | 21 | 2.45 (0.76–7.85) | .16 |

| LTI diagnosis | ||||||||

| TB contact tracing | 675 | 61 | 578 | 86 | 67 | 10 | Ref | |

| At-risk population screening | 438 | 39 | 342 | 78 | 82 | 19 | 2.06 (1.45–2.93) | <.001 |

| Immigration | ||||||||

| No | 320 | 29 | 280 | 88 | 18 | 6 | Ref | |

| Yes | 793 | 71 | 640 | 81 | 131 | 17 | 3.2 (1.92–5.35) | <.001 |

| Geographical origin | ||||||||

| Africa | 245 | 31 | 188 | 77 | 50 | 20 | 2.9 (1.77–4.85) | <.001 |

| Asia | 274 | 35 | 237 | 86 | 29 | 11 | 1.3 (0.77–2.34) | .32 |

| Eastern Europe and Romania | 56 | 7 | 35 | 63 | 9 | 16 | 2.8 (1.23–6.51) | .025 |

| Latin America | 193 | 24 | 164 | 85 | 22 | 11 | 1.4 (0.81–2.68) | .21 |

| Spain and EU | 349 | 31 | 298 | 86 | 27 | 7 | Ref | |

| Years of residence in the Spain (immigrants) | ||||||||

| 2 | 509 | 64 | 424 | 83 | 68 | 13 | Ref | |

| <2 | 284 | 36 | 214 | 75 | 64 | 23 | 1.86 (1.27–2.72) | <.001 |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Low | 590 | 474 | 80 | 97 | 16 | 5.11 (1.83–14.23) | .0002 | |

| Mean | 289 | 244 | 84 | 32 | 11 | 3.2 (1.13–9.51) | .019 | |

| High | 110 | 100 | 91 | 4 | 4 | Ref | ||

| Family situation | ||||||||

| Living in a family | 674 | 623 | 92 | 51 | 8 | Ref | ||

| Not living in a family | 319 | 252 | 79 | 67 | 21 | 3.2 (2.19–4.80) | <.001 | |

| Working situation | ||||||||

| Active | 518 | 449 | 87 | 46 | 9 | Ref | ||

| Unemployed | 279 | 205 | 73 | 65 | 23 | 3.09 (2.04–4.67) | <.001 | |

| Others | 303 | 253 | 83 | 35 | 12 | 1.35 (0.84–2.15) | .22 | |

| Alcohol consumption (> 60 g/day) | ||||||||

| No | 962 | 810 | 84 | 116 | 12 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 149 | 110 | 74 | 31 | 21 | 1.96 (1.26–3.06) | .003 | |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| No | 793 | 669 | 84 | 92 | 12 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 305 | 241 | 79 | 54 | 18 | 1.62 (1.12–2.35) | .009 | |

| Drug use | ||||||||

| No | 1083 | 898 | 83 | 142 | 13 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 29 | 21 | 72 | 7 | 24 | 2.1 (0.88–5.04) | .09 | |

| Adverse effects | ||||||||

| No | 830 | 775 | 93 | 43 | 5 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 172 | 141 | 82 | 6 | 3 | 0.76 (0.32–1.83) | .6 | |

| Liver toxicity | ||||||||

| No | 889 | 823 | 93 | 46 | 5 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 106 | 89 | 84 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 (0.02–1.47) | .11 | |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; TLTI: treatment of latent tuberculosis infection; 3RH: rifampicin + isoniazid for 3 months; 6H: isoniazid for 6 months; Ref: reference population.

TLTI was indicated as a result of contact tracing in 675 (61%) individuals, and screening of the at-risk population in 438 (39%). The TLTI regimen of choice was the combination of isoniazid and rifampicin for 3 months, which was indicated in 1017 patients (91%). The 6-month isoniazid regimen was reserved for patients in whom rifampicin was contraindicated to avoid interactions with their regular medication. Monotherapy with rifampin for 4 months was used in patients with TLTI indicated due to contact with patients with active TB known to be isoniazid-resistant, and as a rescue drug when isoniazid was withdrawn for liver toxicity.

In total, 920 patients (83%) completed treatment and 150 (13%) dropped out. Adverse effects (AE) were recorded in 274 patients (24%), the most common being raised liver enzymes (106; 10%). TLTI was withdrawn in only 43 patients who reported AE (4%). In 42 (4%) cases, the initially indicated regimen was switched; of these, 98% completed the TLTI.

Variables related to dropout in the logistic regression analysis were: diagnosis by screening of at-risk population (OR 2.06; 95% CI 1.45–2.93), male sex (OR 1.79; 95% CI 1.20–2.65), age less than 35 years (OR 1.76; 95% CI 1.14–2.73), not living with family (OR 3.2; 95% CI 2.19–4.80), low educational level (OR 5.11; 95% CI 1.83–14.13), unemployment (OR 3.09; 95% CI 2.04–4.68), smoking (OR 1.62; 95% CI 1.12–2.35), alcoholism (OR 1.96; 95% CI 1.26–3.06), and immigration (OR 3.2; 95% CI 1.92–5.35). Among the subgroup of immigrants, worse compliance was observed in those who had resided for less than 2 years in Spain (OR 1.86; 95% CI 1.27–2.72).

We believe that 3-month course of combined isoniazid and rifampicin usually used in our hospital is the main factor contributing to the TLTI completion rates that we observed. The use of short regimens based on rifampicin alone or in combination with other drugs has been shown to improve TLTI completion rates compared to long regimens with treatments of 6–9 months, and this is considered a fundamental strategy for improving adherence, while maintaining the same efficacy as the traditional regimens.3,6 In a clinical trial conducted by our group, the use of a combination of isoniazid and rifampicin during 3 months showed a rate of compliance (72%) significantly higher than the 6-month isoniazid regimen (52%), with no differences in AE incidence, liver toxicity or efficacy.7

The diagnosis of LTI also influences subsequent compliance with the TLTI. Patients who are prescribed TLTI as the result of contact tracing adhere better to treatment (86%) than those in whom TLTI was prescribed as a result of at-risk population screening (78%). A recently published review that collected TLTI completion rates from 13 prospective studies shows that compliance among recent contacts of active TB cases was 53%–82% compared with 25%–71% of individuals detected in screening programs. This behavior was attributed to the lack of perception of risk in the latter group.8

In our review, AE and liver toxicity were not associated with TLTI dropout, in contrast to the findings of other authors.9 During the study, around 25% of patients reported some type of AE, although the monthly visits and easy access to the tuberculosis clinic whenever symptoms appeared helped us to initiate measures to resolve problems, thus avoiding dropout. Elevated transaminases were the most common AE: 89% of cases were asymptomatic, and only 12 patients were classified as severe (1%), figures similar to other studies.10,11 Analytical monitoring, temporary suspension of treatment and/or a change in regimen usually ensured successful completion of treatment.

The most important sociodemographic factors associated with lack of compliance were young age, worse social situation, such as not living in a family, low educational level, unemployment, and immigration. These factors have been described previously by other authors as predictors of compliance failure.12,13

In conclusion, TLTI compliance in our center was satisfactory. Although the appearance of AEs was very common, these were easily resolved with close monitoring by expert personnel and easy access to the clinic, facilitating completion of the TLTI.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez-Fuentes MÁ, Augé CM, Peiró JS, Souza-Galvão MLd. Tratamiento de la infección tuberculosa latente en una unidad clínica de tuberculosis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:484–486.