Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is associated with low exercise tolerance, dyspnea, and decreased health-related quality of life (HRQL). Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is one of the most prevalent in the group. A specific version of the Saint George's questionnaire (SGRQ-I) has been developed to quantify the HRQL of IPF patients. However, this tool is not currently validated in the Spanish language. The objective was to translate into Spanish and validate the specific Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (SGRQ-I).

MethodsThe repeatability, internal consistency and construct validity of the SGRQ-I in Spanish were analyzed after a backtranslation process.

ResultsIn total, 23 outpatients with IPF completed the translated SGRQ-I twice, 7 days apart. Repeatability was studied, revealing good concordance in test–retest with an ICC (interclass correlation coefficient) of 0.96 (P<.001). Internal consistency was good for different questionnaire items (Cronbach's alpha of 0.9 including and 0.81 excluding the total value) (P<.001).

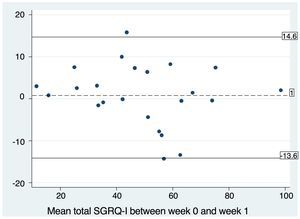

The total score of the questionnaire showed good correlation with forced vital capacity FVC% (r=−0.44; P=.033), diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO%) (r=−0.55; P=.011), partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood PaO2 (r=−0.44; P=.036), Medical Research Council Dyspnea scale (r=−0.65; P<.001), and number of steps taken in 24h (r=−0.47; P=.024).

ConclusionsThe Spanish version of SGRQ-Ideveloped by our group shows good internal consistency, reproducibility and validity, so it can be used for the evaluation of quality of life (QOL) in IPF patients.

Las enfermedades pulmonares intersticiales (EPI) se asocian a una baja tolerancia al ejercicio, disnea y disminución de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS). La fibrosis pulmonar idiopática (FPI) es una de las más prevalentes del grupo. Para cuantificar su CVRS, se ha desarrollado una versión específica del cuestionario Saint George (SGRQ-I). Sin embargo, esta herramienta no está actualmente validada en el idioma español. El objetivo fue traducir al idioma español y validar el SGRQ-I en pacientes con FPI.

MétodosSe estudiaron la repetibilidad, la consistencia interna y la validez de constructo del SGRQ-I en español obtenido luego del proceso de traducción reversa.

ResultadosVeintitrés pacientes con FPI completaron 2 veces el cuestionario traducido con 7 días de diferencia cada uno. Encontramos una buena concordancia en el test-retest, con un coeficiente de correlación intraclase (CCI) de 0,96 (p<0,001). En el estudio de la consistencia interna hallamos un coeficiente alfa de Cronbach de 0,9 al incluir al valor total, y de 0,81 al excluirlo (p<0,001), lo cual evidencia una buena interrelación de los diferentes ítems del cuestionario.

El valor total del cuestionario mostro buena correlación con FVC% (r=–0,44; p=0,033), DLCO% (r=–0,55; p=0,011), PaO2 (r=–0,44; p=0,036), disnea escala modificada de Medical Research Council (r=–0,65; p<0,001), y pasos dados en 24h (r=–0,47; p=0,024).

ConclusiónLa versión en español del SGRQ-I desarrollada por nuestro grupo tiene buena consistencia interna, es reproducible y es válida para evaluar calidad de vida en pacientes con FPI.

Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are associated with low exercise tolerance, increased dyspnea, and reduced health-related quality of life.1,2 The same tools used in other respiratory diseases to quantify these factors are also used in ILD, including the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) to evaluate exercise tolerance (and other aspects), and the Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) to measure quality of life.3–5 The SGRQ is a self-administered questionnaire with 3 domains that explore different disease aspects, including a special section for evaluating accompanying symptoms.6 Recent studies have demonstrated that this questionnaire is less than optimal for evaluating the quality of life of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and it has been found to be deficient particularly in the symptoms domain.7 This may be because this domain of the questionnaire addresses cough, sputum, wheezing, and respiratory failure, symptoms that are prevalent in other diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchial asthma, bronchiectasis, etc.,6,8,9 but uncommon in IPF patients.

The SGRQ-I is a modified version of this specific HRQoL questionnaire that has recently been validated in patients with IPF. This model showed good internal consistency and correlation with prognostic variables and disease severity.10 However, no validated tool is currently available in Spanish to specifically assess quality of life in IPF patients.

Since clinical trials carried out to date have not yet identified drugs that can reduce mortality in this disease, improving quality of life is a major objective in the treatment of these patients.11,12 The importance, then, of having a valid, reliable and reproducible tool to evaluate quality of life in IPF cannot be overstated. The aim of this study was to translate and validate a Spanish version of the SGRQ-I.

MethodsTranslation of the QuestionnaireSGRQ is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 50 items, divided into 3 domains: symptom (S) with 8 items, activity (A) with 16 items, and impact (I) with 26 items. These 3 domains, which consist of multiple-choice and true-false questions, are then pooled to obtain a final result with a total score (T). The result is a numeric value (0–100) for each domain that is expressed as a continuous variable, in which the patients with higher scores have a worse quality of life.6 An adapted version of the SGRQ, the SGRQ-I, was developed and validated to create a specific tool for IPF patients. To this end, some questions (2 on symptoms, 6 on activities, and 8 on impact) that may have been unsuitable for evaluating IPF patients were deleted, and some response categories were combined, leaving 34 items (6 for symptoms, 10 for activities, and 18 for impact).10

Authorization to translate the questionnaire was obtained from the copyright holders. Two translations of the questionnaire from English to Spanish were made by 2 separate healthcare professionals (trained in the use of this type of tools) from our hospital team. A single, consolidated version of both questionnaires was then produced. To ensure that the translation was generic and applicable to the overall Spanish-speaking population, and to avoid the use of local expressions, it was reviewed by the Department of Linguistics of the Ibero-American Society of Scientific Information (SIIC), who offered their advice. This version was then backtranslated into English by 2 qualified translators. Finally, both versions in English (the original version and the backtranslation) were compared and found to contain no significant differences (Fig. 1).

Patients and MeasurementsPatients with a diagnosis of IPF confirmed by the multidisciplinary group of ILD specialists using ATS/ERS/ALAT 2011 criteria4 were enrolled consecutively between January 2016 and January 2017. Patients were asked to complete the Spanish version of the SGRQ-I during the first visit, and to complete it again 1 week later, without receiving any intervention in the intervening period. Demographic data were recorded. Lung function tests were performed and forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) were recorded. Habitual dyspnea was determined using the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale. Exercise tolerance was evaluated using the 6MWT, and minimum saturation and meters walked were recorded. These tests were performed according to the recommendations of the relevant scientific societies.13,14 Arterial blood was drawn to determine PaO2. Physical activity levels were recorded over 6 days (4 week days and 2 weekend days) using the SenseWear Armband (BodyMedia Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA), a multisensor device that has been widely used in patients with COPD and IPF.15–17 Patients were instructed to use the accelerometer 24h a day except during personal hygiene activities. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital de Rehabilitación Respiratoria María Ferrer de Buenos Aires, Argentina. All patients gave informed consent in writing.

Questionnaire ValidationThe repeatability of the questionnaire was evaluated using the test–retest technique with an interval of 1 week between measurements. Before the second measurement, patients were asked if they had experienced any worsening or appearance of any new symptom in the previous week. Patients who answered in the affirmative were excluded.

The internal consistency of the questionnaire was evaluated to determine the correlation between the different items in the SGRQ-I. The construct validity of the questionnaire was evaluated on the basis of its correlation with the following variables: FVC%, DLCO%, total lung capacity % (TLC%), arterial PO2 and meters walked in the 6MWT. These variables were selected because they reflect disease severity. The correlation with the mMRC dyspnea scale was measured because dyspnea is the principal and most limiting symptom of IPF. The correlation of the questionnaire with the number of steps taken by the patient over 24h was also studied, on the understanding that mobility limitation is associated with a worse quality of life.15

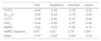

StatisticsContinuous variables were described as mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range, depending on their distribution. Categorical variables were described according to their frequency. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and the Bland–Altman plot were used to study repeatability. Repeatability was considered acceptable when the ICC was greater than or equal to 0.7. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was used to study internal consistency. Internal consistency was considered acceptable when the coefficient was greater than or equal to 0.7. The Pearson's or Spearman's test was used to analyze correlations, depending on whether the distribution was normal or non-normal, respectively. Correlation was considered weak when the r value was less than 0.3, moderate between 0.3 and 0.6, and strong when greater than 0.6.7 A P value ≤.05 was considered significant.

STROBE initiative recommendations for reporting results from observational studies were followed.18

ResultsA total of 27 patients were recruited consecutively for the purpose of administering the questionnaire. Two patients who did not return 1 week later to complete the questionnaire again were excluded, and 2 patients were excluded after they reported a change in symptoms during the intervening period. The characteristics of the 23 study patients are shown in Table 1. When repeatability was examined, we found good test–retest concordance, with an ICC of 0.96 (P<.001). The Bland–Altman plot also revealed good concordance between the 2 measurements (Fig. 2). The mean difference between the test–retest values was 0.83, with a P value for the paired t-test of .581 (95% CI, 2.25–3.92). We can therefore confirm that this value does not differ significantly from zero, i.e., that there was no significant difference between patient responses at the first visit (T0) and at 1 week.

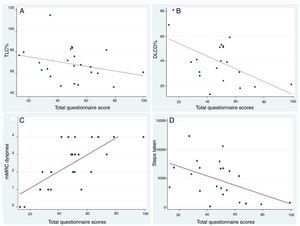

Demographic, Clinical and Functional Characteristics of IPF Patients Included in the Validation Study of the Spanish Version of the SGRQ-I.

| Variable | Total=23 Patients |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 71.9 (6.6) |

| Sex, men, n (%) | 18 (78.2) |

| FVC%, mean (SD) | 68.9 (15.5) |

| DLCO%, mean (SD) | 39.7 (17.8) |

| TLC%, mean (SD) | 62.52 (12.9) |

| PaO2 mmHg, mean (SD) | 70.6 (13.6) |

| 6MWT, mean (SD) | 378.5 (92.2) |

| SGRQ-I symptoms, mean (SD) | 58.1 (23.8) |

| SGRQ-I activity, mean (SD) | 70.5 (18.1) |

| SGRQ-I impact, mean (SD) | 36 (24.1) |

| Total SGRQ-I, mean (SD) | 49.3 (20.1) |

| Steps, mean (SD) | 4720 (3372) |

| mMRC dyspnea, median (IQR) | 3 (1–4) |

6MWT: meters walked in 6-minute walk test; DLCO%: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide %; FVC%: forced vital capacity %; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale; PaO2: arterial partial pressure of oxygen; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; SGRQ-I: specific Saint George's quality of life questionnaire for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; TLC%: total lung capacity %.

In the internal consistency study, we found a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.9 when the total score was included, and 0.81 when it was excluded (P<.001), providing evidence of a good correlation between the different items in the questionnaire.

The total score of the questionnaire showed good correlation with FVC% (r=−0.44; P=.033), DLCO% (r=−0.55; P=.011), PaO2 (r=−0.44; P=.036), mMRC dyspnea (r=−0.65; P<.001) and steps taken in 24h (r=−0.47; P=.024) (Fig. 3). The correlation between the different items of the questionnaire and all the variables used to examine construct validity are shown in Table 2.

Scatter plot with the line of best fit for the correlation between the total SGRQ-I score and the variables FVC%, DLCO%, mMRC dyspnea and number of steps taken. (A) Correlation between the total SGRQ-I score and FVC% (forced vital capacity %) (r=−0.44; P=.033; beta coefficient=−0.22). (B) Correlation between the total SGRQ-I score and DLCO% (diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide %) (r=−0.55; P=.011; beta coefficient=−0.60). (C) Correlation between the total SGRQ-I score and mRMC dyspnea score (r=0.71; P<.001; beta coefficient=0.047). (D) Correlation between the total SGRQ-I score and steps taken by the patient in 24h measured by accelerometer (r=0.47; P=.024; beta coefficient=−81.08).

Correlation Between the Spanish SGRQ-I Domains and Variables Used for Validation.

| Total | Symptoms | Activities | Impact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVC% | −0.44* | −0.45* | −0.42* | −0.35 |

| DLCO% | −0.55* | −0.23 | −0.76* | −0.44* |

| TLC% | −0.49* | −0.40 | −0.43* | −0.43* |

| PaO2 | −0.44* | −0.26 | −0.57* | −0.36 |

| 6MWT | −0.25 | −0.33 | −0.35 | −0.15 |

| mMRC dyspnea | 0.65* | 0.53* | 0.79* | 0.54* |

| Steps | −0.47* | −0.43* | −0.62* | −0.34 |

6MWT: meters walked in 6-minute walk test; DLCO%: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide %; FVC%: forced vital capacity %; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale; PaO2: arterial partial pressure of oxygen; TLC%: total lung capacity %.

In this study, we translated and validated the SGRQ-I questionnaire for use in Spanish. We showed that the questionnaire has good reproducibility, with a good ICC in the test–retest procedure, and good internal consistency, evaluated with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Moreover, we studied the construct validity of the tool by examining its correlation with variables that reflect the severity of the disease, limitations in activities of daily living, and the dominant symptom (dyspnea). Values above the previously established cutoff for acceptability were obtained in all cases.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, we believe it would have been preferable to determine the correlation with another tool specifically validated for measuring quality of life in IPF. However, this was impossible, since no other such tool was available in the Spanish language. Although Yorke et al. used the SF-36 questionnaire to evaluate the construct validity during the development of the SGRQ-I, we decided not to use this instrument as it is a questionnaire that assesses the overall health of the patient and, as a result, may be biased by non-respiratory problems. Secondly, we believe it would have been useful to study the variability of the questionnaire over time, or after some type of intervention (e.g., pulmonary rehabilitation), in order to estimate its sensitivity to change and to determine the minimum clinically significant change. Thirdly, our study is limited by its sample size. Nevertheless, the prevalence of IPF must be taken into consideration: according to the strictest definition, prevalence is between 14 and 27.9 cases per 100000 inhabitants, and between 42.7 and 63 cases per 100000 if a wider definition of IPF is used.19 Some authors recommend a cohort of between 30 and 40 patients for translation and validation studies, whereas other investigators have obtained satisfactory results with sample sizes similar to ours.20,21 We believe that the validation of a specific questionnaire for evaluating the quality of life of IPF patients is of vital importance, since the tools available so far were designed for other respiratory diseases, and do not adapt well to this disease. Swigris et al. reviewed 30 studies in which the psychometric properties of the SGRQ were evaluated in IPF patients. They found an excellent internal consistency in the activities and impact domains and in the total score. However, internal consistency in the symptoms domain was moderate, with values below 0.7 in the majority of the studies included in the review. This is probably because this area of the questionnaire addresses a series of respiratory symptoms (cough, sputum, shortness of breath, wheezing, and respiratory failure) that are the dominant symptoms of other diseases, such as COPD or asthma, but which are not common in patients with IPF.22,23

We included variables that refer to disease severity in the theoretical construct developed for evaluating the validity of the questionnaire, on the understanding that patients with more severe disease should have the poorest quality of life.24 We found a good correlation between the total SGRQ-I score and FVC%, DLCO and PaO2 values, with results similar to those shown in other studies.7 The above-mentioned review article found r values of between −0.30 and −0.66 for these variables, similar to those of our group. The correlation between the same variables and the activities domain was moderate to strong (r=−0.42 to −0.76), echoing Swigris et al. (r=−0.38 to –0.65). In these studies, correlation was weak to moderate in the symptoms (r=−0.21 to −0.46) and impact (r=−0.24 to 0.39) domains, similar to the results found in our study.7 Our group also studied the correlation of the questionnaire with the mMRC dyspnea scale, as dyspnea is the dominant and most limiting symptom of this disease, with the greatest impact on quality of life.25,26 A group of authors who studied patients with IPF caused by systemic sclerosis found a moderate correlation between the total SGRQ score and the mMRC dyspnea grade (r=0.41).27 Although our patients have a different diagnosis, making comparison difficult, our results showed that this variable correlates best for the total score and for all domains of the questionnaire.

We believe that the inclusion of a step counter in the theoretical construct used for the validation of the tool is a novel and relevant addition that adds strength to our study. Limitations in physical activity has a clear impact on a patient's quality of life, and counting steps appears to reliably measure this aspect of IPF.28–30 A group of authors who studied the correlation between steps taken (measured with the same device as used in our study) and other clinical variables found similar values to our group when results were correlated with total SGRQ scores (r=−0.5 and −0.47, respectively).15 Data reported by the group who developed the specific version of the SGRQ questionnaire for IPF (SGRQ-I) do not differ significantly from those obtained by our team during the validation of the Spanish version (Table 3). Interestingly, however, we obtained a better correlation than the original authors in many questionnaire items, thus demonstrating the validity of this version of the tool in assessing quality of life.10

Comparison of Correlation Coefficients Obtained in the Validation of SGRQ-I in English and Those Obtained in the Validation of the Spanish Version.

| Total | Symptoms | Activities | Impact | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGRQ-I English | SGRQ-I Spanish | SGRQ-I English | SGRQ-I Spanish | SGRQ-I English | SGRQ-I Spanish | SGRQ-I English | SGRQ-I Spanish | |

| FVC% | −0.33 | −0.44 | −0.25 | −0.45 | −0.30 | −0.42 | −0.31 | −0.35 |

| DLCO% | −0.37 | −0.55 | −0.25 | −0.25 | −0.33 | −0.76 | −0.36 | −0.41 |

| 6MWT | −0.28 | −0.25 | −0.12 | −0.33 | −0.30 | −0.35 | −0.26 | −0.15 |

6MWT: meters walked in 6-minute walk test; DLCO%: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide %; FVC%: forced vital capacity %; SGRQ-I: specific Saint George's quality of life questionnaire for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

In conclusion, given that IPF is a progressive disease with a poor prognosis, for which effective drugs have not yet been developed, health-related quality of life is an important parameter both in research and clinical practice. The Spanish version of the SGRQ-I developed by our group has good internal consistency, and is reproducible and valid for assessing quality of life in patients with IPF.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Capparelli I, Fernandez M, Otero MS, Steimberg J, Brassesco M, Campobasso A, et al. Traducción al español y validación del cuestionario Saint George específico para fibrosis pulmonar idiopática. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:68–73.