Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis is an essential determination for all healthcare professionals specializing in the respiratory system. Errors in measuring and interpreting ABG analysis may cause direct injury to the patient, so accurate calculations are essential.

We are still far from achieving standardization in both the collection and subsequent analysis of samples. Although all clinical practice guidelines in the literature agree that samples should ideally be analyzed as soon as possible, we are still surprised to find ambiguities and discrepancies in the maximum time permitted before analysis, without the sample deteriorating.1–6

It is generally accepted that ABG values change over time: oxygen is consumed and carbon dioxide increases. It is assumed that erythrocyte metabolism continues outside the body, causing pCO2 levels to increase in the sample.7 Because of this assumption, most clinical practice guidelines recommend storing the blood samples on ice, in the hope that this will slow down metabolism and avoid wide variations in ABG values.5,8

Our goal was to analyze the impact of time on ABG values between the extraction of samples and analysis, and the factors that influence such variations. We therefore designed a prospective study of the analyses requested by our department over a period of 1 month. The recommendations and the SEPAR protocol1,6 were followed throughout the entire process. Two analyses were conducted on each sample using a BD-Preset syringe; 1 baseline sample, performed within the normal timeframe, and the other 30min after the first. During this interval, the samples were preserved on ice, according to protocol.

Data were collected from several variables: the patient (age, sex, height, weight, smoking habit, associated diseases, and lung function), the environment (barometric pressure and temperature), and ABG determinations (FiO2, pO2, pCO2, pH, O2Hb, COHb).

The sample size was calculated based on the difference between the final pO2 and the initial pO2; for a power of 80% and an alpha error <0.05, the minimum N was 43.9

An intra-subject t-test for dependent variables was conducted, and correlations among the different variables were also compared using the Pearson's test.

A total of 69 patients was finally included. In the baseline measurement, mean ABG values were: pO2 63mmHg (SD 15), pCO2 45mmHg (SD 10), and pH 7.42 (SD 0.037). Mean differences between the final measurement and the initial analysis were observed in pO2, +2.26mmHg (66.02 final vs 63.78 initial, P<.001), and pCO2, −0.30mmHg (45.48 final vs 45.78 initial; P=.017). There was a 0.007 difference in pH compared to the baseline value (7.416 final vs 7.424 initial; P<.001).

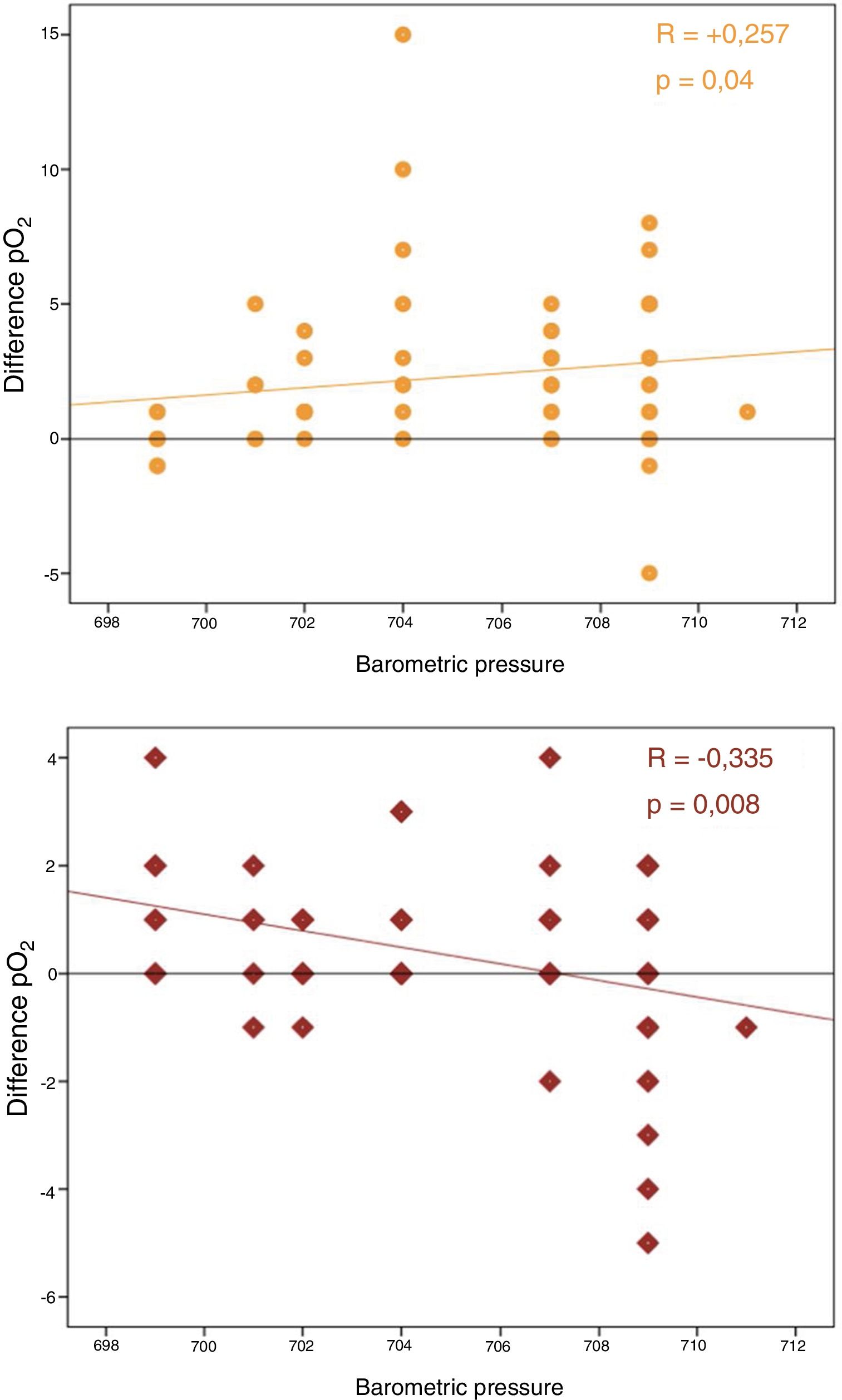

No correlation was observed between differences in pO2 and time to analysis. In contrast, a significant correlation was found between barometric pressure and differences in pCO2 and pO2 (P<.05) (Fig. 1).

No other associations were found between differences in gases and the other variables studied, including comorbidities and various respiratory pathologies.

In contrast to the recommendations of some clinical practice guidelines and widespread medical beliefs, the changes observed in ABG (pO2, pCO2 and pH) were opposite to expected. An increase was observed in pO2 and a decrease in pCO2 in the second analysis compared to baseline.

This fact, while remarkable, has already been previously described in other studies: Liss and Payne8 conducted an analysis similar to ours, and found similar results. Knowles et al.,10 Schmidt and Muller-Plathe,11 and Pretto and Rochford12 went further, and reported that the variation in gases differed depending on the material of the syringe. Indeed, they showed that no such variations occurred with glass syringes.

Different theories have been proposed to explain these modifications in the gases of the samples, but all have a common denominator: the diffusion of gases through the porous plastic material of the syringes. Perhaps the most widely accepted hypothesis is that gas diffusion as a function of oxygen content in the sample is due to a purely physical mechanism, as demonstrated in the study of Mahoney et al.9 Fletcher and Barber13 also supported physical diffusion, to the detriment of the theories that take into account blood cell metabolism: these authors studied changes in the concentration of pO2 of oxygenated water, avoiding the use of blood per se, and obtained similar results.

It is important to note that in studies with a higher initial pO2 than ambient pO2, the diffusion gradient of the gases is reversed and pO2 diminishes with time,12,14 a finding that only goes to reinforce the hypothesis of simple gas diffusion.

Our results also clearly support this physical diffusion theory, since pO2 variability increases depending on atmospheric pressure in a statistically significant manner, a factor that had never been previously analyzed.

In summary, it seems clear that over time, pO2 in ABG tends to increase, and that this variation could be directly associated with plastic syringes and the diffusion of gases through this porous material. Our study supports this theory and reveals a direct relationship of these variations with atmospheric pressure.

Despite the fact that ABG determinations vary significantly with time, they do so to an extent that is insignificant in clinical practice. It may be of interest, in the future, to expand the study to different time points.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-García A, Ruiz Albi T, Santos Plaza JI, Crespo Sedano A, Sánchez Fernández A, López Muñiz G, et al. Impacto del tiempo entre la extracción y el análisis de la gasometría arterial en la práctica clínica. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019;55:501–502.