The emergence of a fixed-dose combination (FDC) of a long-acting ß2-agonist (LABA), a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) in a single inhalation device has changed the approach to inhaled therapy. Although clinical trials describe the efficacy and safety of these FDCs, their use in daily clinical practice can present challenges for the clinician in two specific scenarios. In patients who are already receiving triple therapy via different devices, switching to FDCs could confer benefits by reducing critical errors in the management of inhalers, improving therapeutic adherence, and lowering costs, while maintaining the same clinical efficacy. In patients who are not receiving triple therapy in different devices and who require a change in treatment, triple therapy FDC has shown benefits in clinical trials. Although methodological differences among the trials advise against direct comparison, clinical results show good efficacy, but also considerable variability, and a number of clinical outcomes have yet to be explored. In the future, trials must be developed to complete clinical efficacy data. Real-world efficacy trials are needed, and studies must be designed to determine the profile of patients who present a greater therapeutic response to each FDC in order to pave the way towards more personalized treatment.

La aparición de la denominada triple terapia inhalada mediante la combinación de un agonista ß2 de acción prolongada (LABA), un antimuscarínico de acción prolongada (LAMA) y un corticoide inhalado (ICS) en una combinación a dosis fijas (CDF) en un solo dispositivo de inhalación ha supuesto un cambio en el uso de este tratamiento. A pesar de que los ensayos clínicos nos aportan una idea de la eficacia y seguridad de estas CDF, su aplicación a la clínica diaria puede presentar retos para el clínico sobre dos escenarios concretos. En pacientes que ya están recibiendo una triple terapia en dispositivos distintos, el cambio a una CDF podría suponer beneficios en disminución de errores críticos en el manejo de los inhaladores, mayor adherencia el tratamiento y menor coste, manteniendo la misma eficacia clínica. En pacientes que no están recibiendo una triple terapia en dispositivos distintos y que necesiten un cambio en el tratamiento, la CDF de triple terapia presenta beneficios mostrados en los ensayos clínicos. Aunque las diferencias metodológicas entre ensayos desaconsejan comparaciones directas, los resultados clínicos muestran una buena eficacia, pero también con una considerable variabilidad y con un número de resultados clínicos aún por explorar. En el futuro deberán desarrollarse ensayos que completen los datos de eficacia clínica, estudios en vida real que informen de su efectividad y trabajos encaminados a descubrir el perfil de paciente que presenta una mayor respuesta terapéutica a cada CDF, con el objeto de avanzar en el tratamiento personalizado.

The use of inhaled triple therapy, consisting of a long-acting ß2-agonist (LABA), a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), has been recommended for years as part of treatment escalation strategies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). To date, triple therapy has been administered in 3 ways: using the 3 drugs separately in 3 inhalation devices, or combining ICS/LABA with a LAMA or LABA/LAMA with ICS in 2 inhalation devices. Despite the fact that no studies have compared which of the 3 ways of administering this combination is the most appropriate, it has been suggested that for patients with COPD, it would make more sense to use LABA/LAMA + ICS, while LABA/ICS + LAMA should be used for asthma.1

The appearance of triple therapy in a fixed-dose combination (FDC) in a single inhalation device has changed the approach to this triple combination, and warrants an analysis of the efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of this combination and its impact on real life experiences. This is particular relevant now, when combinations that contain ICS are being overprescribed both in primary care2 and in the hospital setting,3,4 irrespective of blood eosinophil levels.5 Despite the fact that clinical trials describe the efficacy and safety of these FDCs, their use in daily clinical practice can be challenging, and we believe that some reflection on this matter is needed. This review aims to assess the use of triple therapy in FDC in routine clinical practice in different clinical scenarios.

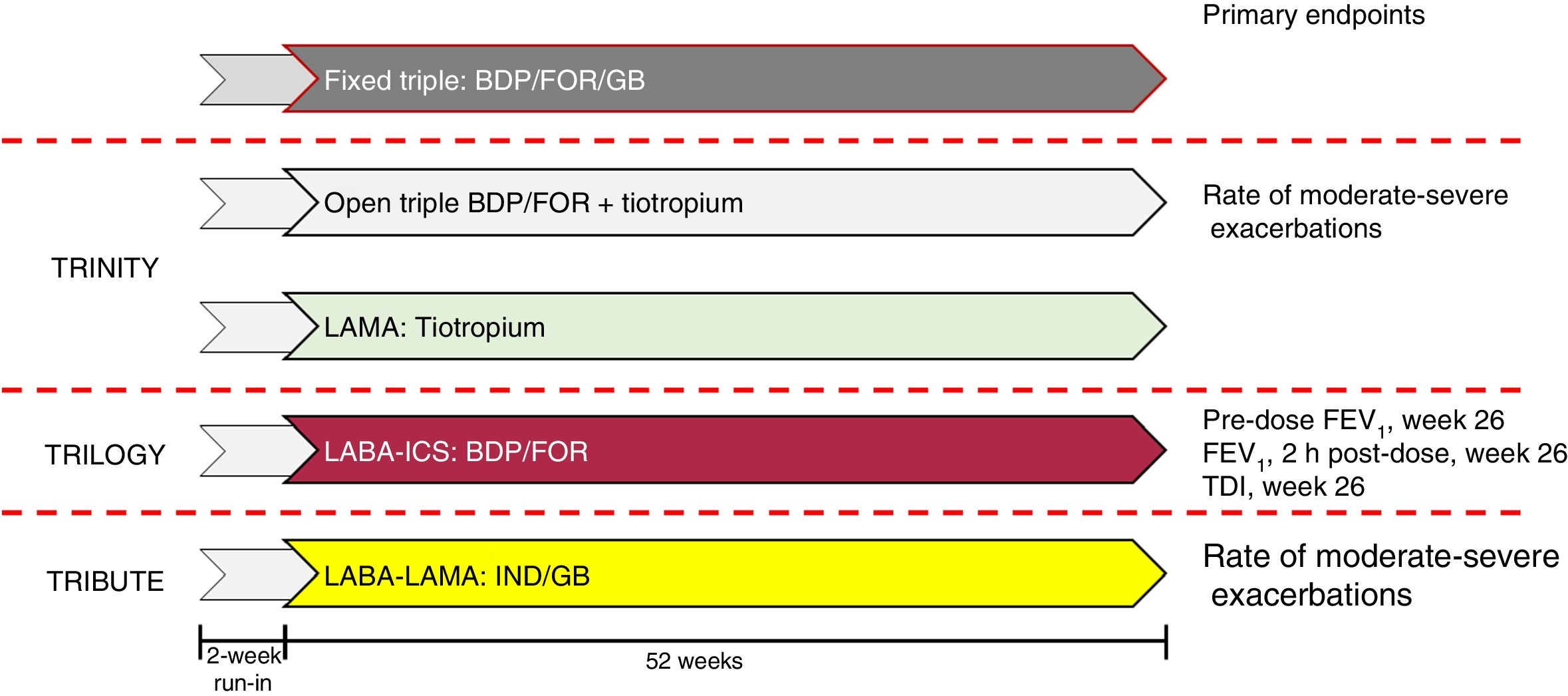

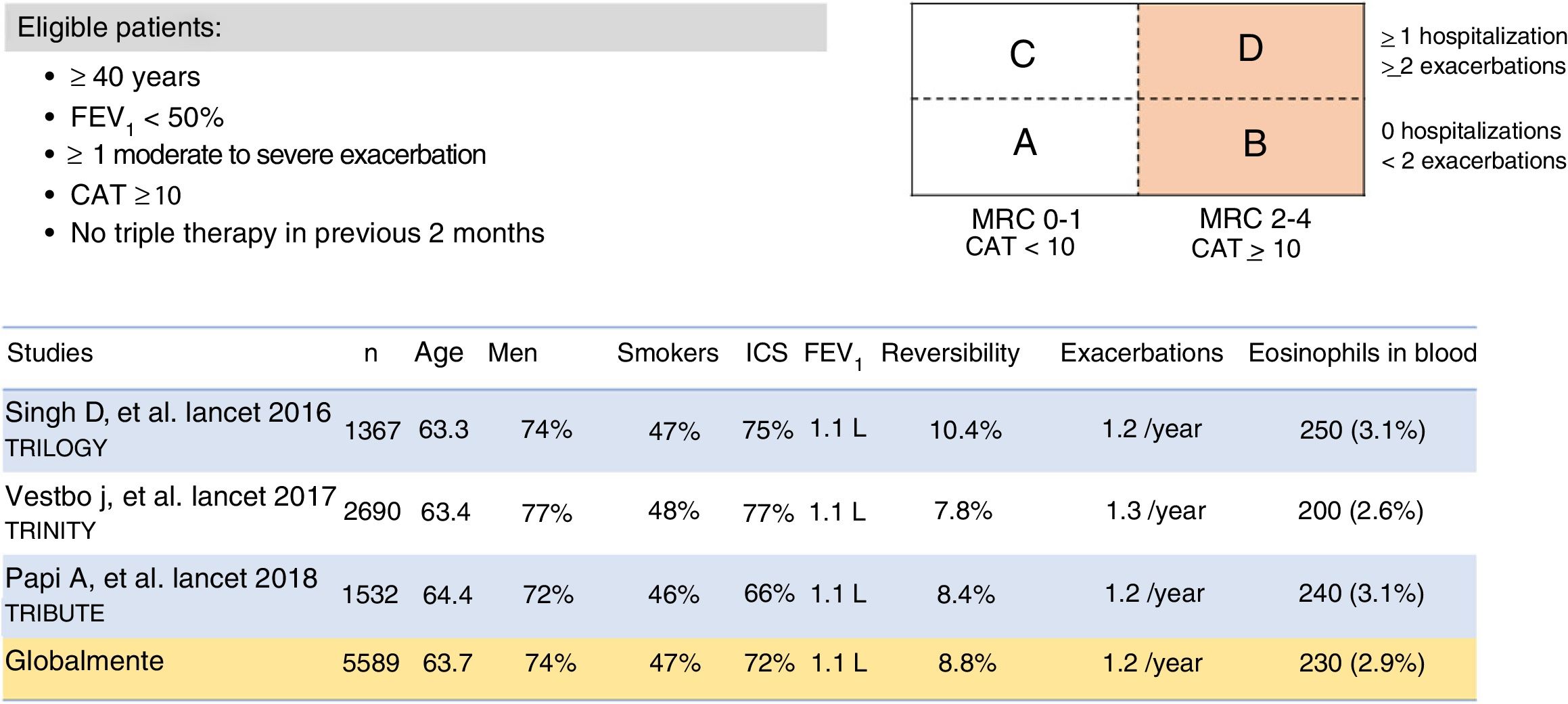

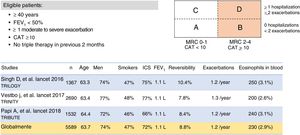

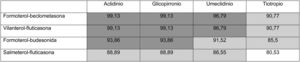

Development of triple therapy FDCFive triple therapy FDCs are currently either under development or already available on the market. The combination of glycopyrronium bromide (GB), formoterol fumarate (FOR), and beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) in a metered dose inhaler (MDI)6 has been studied in 3 different trials (Fig. 1). To summarize, the TRILOGY study randomized 1367 patients to compare triple therapy FDC with BDP/FOR. Although the trial lasted 52 weeks, primary objectives were evaluated at week 26, namely pre-dose forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), post-dose FEV1 at 2 h, and change in Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI).7 TRINITY randomized 2690 patients to compare FDC with tiotropium alone or with an open triple combination of BDP/FOR + tiotropium. The primary endpoint was the annualized rate of moderate-severe exacerbations compared to monotherapy.8 Finally, TRIBUTE randomized 2690 patients to compare FDC with indacaterol IND/GB at a dose of 110/40 once a day. The primary endpoint was the annualized rate of moderate to severe exacerbations.9 Interestingly, the design and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were exactly the same for all 3 studies (Fig. 2).

Design of studies of the combination of BDP/FOR/GB.

BDP: beclomethasone dipropionate; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FOR: formoterol fumarate; GB: glycopyrronium bromate; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; IND: indacaterol; LABA: long-acting ß2-agonist; LAMA: long-acting anticholinergic; TDI: Transition Dyspnea Index.

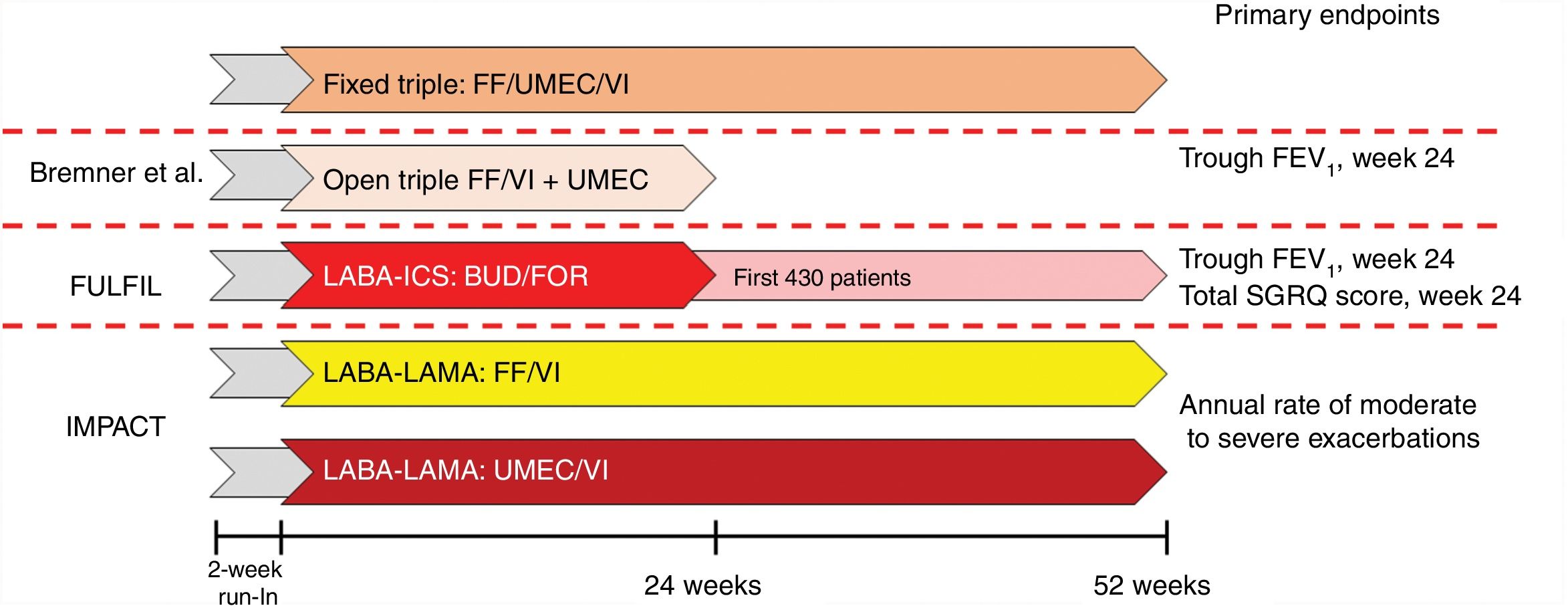

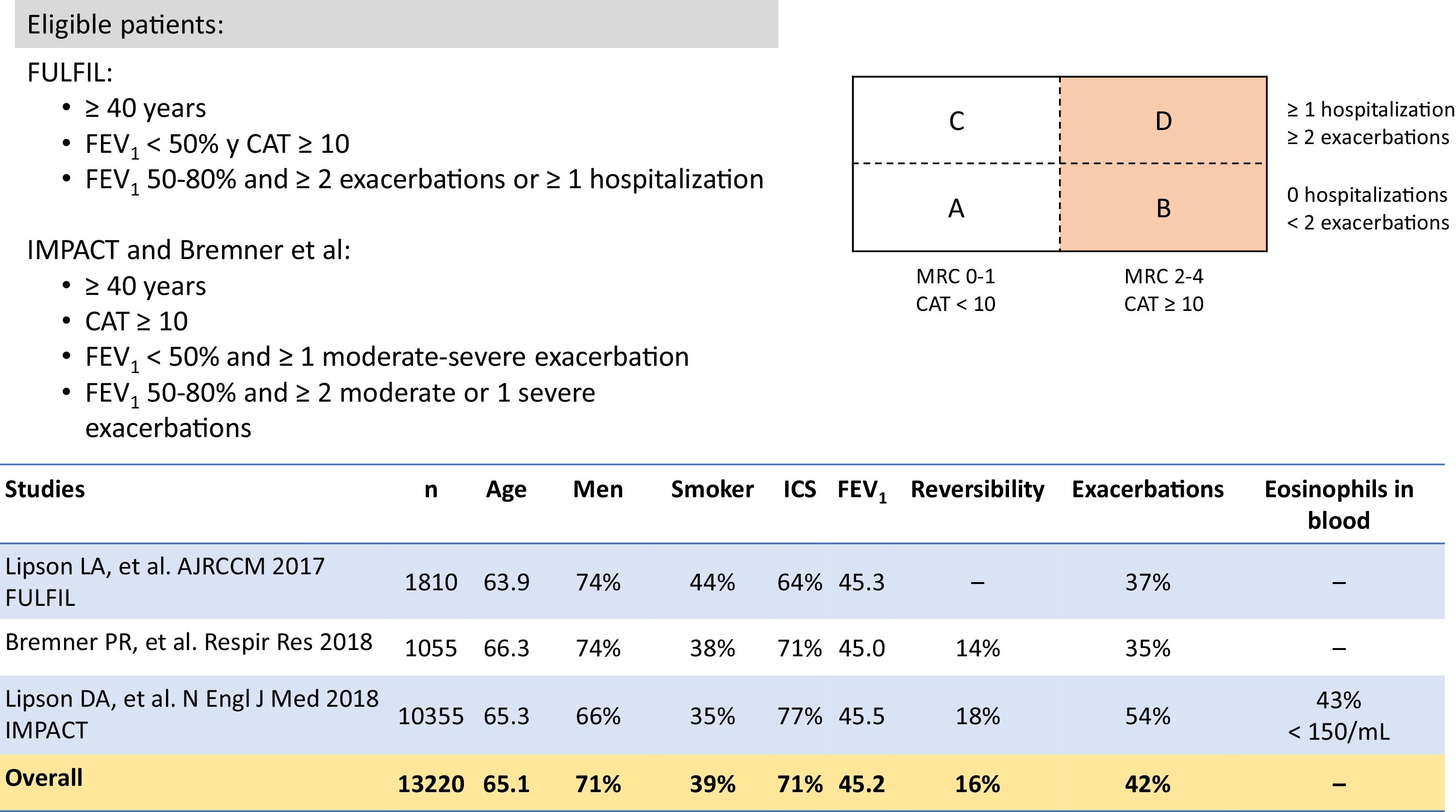

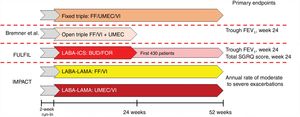

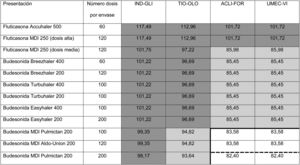

The combination of umeclidinium bromate (UMEC), vilanterol trifenatate (VI), and fluticasone furoate (FF)10 has been evaluated in 3 different trials (Fig. 3). Briefly, FULFIL was a clinical trial that randomized 1810 patients to compare FDC with budesonide BUD/FOR. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in trough FEV1 and St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score at week 24.11 In this trial, a subset of the first 430 patients included continued in the study for up to 52 weeks. Bremner et al.12 randomized 1055 patients using a non-inferiority design to compare triple therapy FDC delivered by the Ellipta device with open triple therapy with FF/VI + UMEC delivered in two separate Ellipta inhalers. The primary endpoint was change from baseline in trough FEV1 at week 24. Finally, the IMPACT trial randomized 10,355 patients to compare FDC with FF/VI and with UMEC/VI, using the annual rate of moderate or severe exacerbations during treatment as the primary efficacy outcome.13

Design of studies of the combination of FF/UMEC/VI.

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FF: fluticasone furoate; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LABA: long-acting ß2-agonist; LAMA: long-acting anticholinergic; SGRQ: St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; UMEC: umeclidinium bromate; VI: vilanterol trifenatate.

The combination of GB/FOR/BUD has been studied in a phase III trial. The KRONOS study14 compared this FDC delivered by MDI with GB/FOR delivered by MDI and with BUD/FOR delivered by Turbuhaler. The primary endpoints were FEV1 area under the curve from 0−4 h and change from baseline in morning pre-dose FEV1 compared to GB/FOR, and non-inferiority compared to BUD/FOR for 24 weeks. Eligible patients were 40–80 years of age, current or former smokers with a history of smoking ≥ 10 pack-years, diagnosed with mild to very severe COPD with an FEV1 of between 25% and 80% and a CAT score ≥ 10 despite receiving 2 or more inhaled maintenance therapies for at least 6 weeks before screening. This study includes patients with different characteristics and with a lower degree of functional involvement than the other 2 FDC trials mentioned above.

Batefenterol/FF is a combination of a molecule with dual antimuscarinic and ß2 agonist activity (MABA), so the therapeutic effect of triple therapy can be provided with 2 drugs. At the moment, only phase I trials with Ellipta devices have been conducted.15 Finally, the combination of mometasone/IND/GB is under development for the treatment of bronchial asthma, but no publications are available yet (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03158311).

Several months after the marketing approval of 2 of these FDC in Spain, BDP/FOR/GB and FF/UMEC/VI, two main clinical scenarios in routine practice are emerging: patients who are already receiving triple therapy in separate devices, and those who are not yet receiving triple therapy.

Patients receiving triple therapy in separate devicesThis clinical scenario affects patients receiving 3 inhaled drugs in separate inhalation devices, possibly with different dose regimens. We propose that these compounds be combined in a single device with a single dosing regimen. As might be expected, handling the new device and possible changes in the daily dosing schedule can have a significant impact on the patient.

In order to justify this change, we must closely monitor patients for any change in pharmacological efficacy and safety profile when an open triple therapy is switched to an FDC. The data for both FDCs have some particularities in this respect that should be mentioned. For the BDP/FOR/GB combination, the TRINITY study found that treatment with FDC achieved clinical benefits comparable to those of open combination.8 The only statistical differences were in quality of life measured by SGRQ at weeks 26 and 52, and in the probability of achieving 4 points in the SGRQ questionnaire at week 26, in favor of the open triple therapy, and in the rate of moderate-severe exacerbations in the subgroup of patients with 2 or more exacerbations in the previous 12 months, in favor of FDC (RR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.511–0.995; p = 0.047).16 A later meta-analysis comparing triple therapy in FDC with open triple therapies found no differences in the risk of moderate-severe exacerbations, hospitalizations, lung function, or quality of life.17

Bremner et al. also concluded that the FF/UMEC/VI combination in FDC was not inferior to triple therapy in two separate inhalers (FF/VI + UMEC) in terms of lung function, symptoms, exacerbations, and safety.12

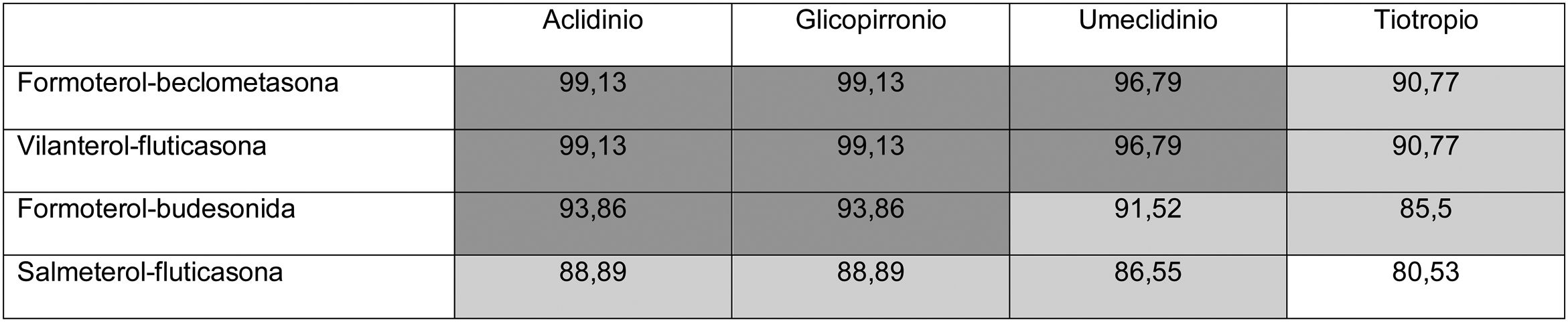

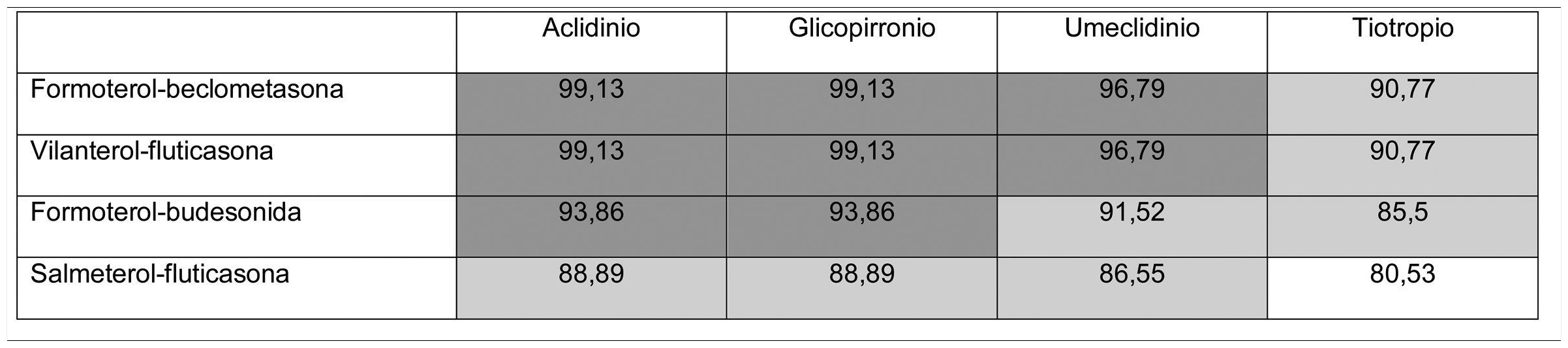

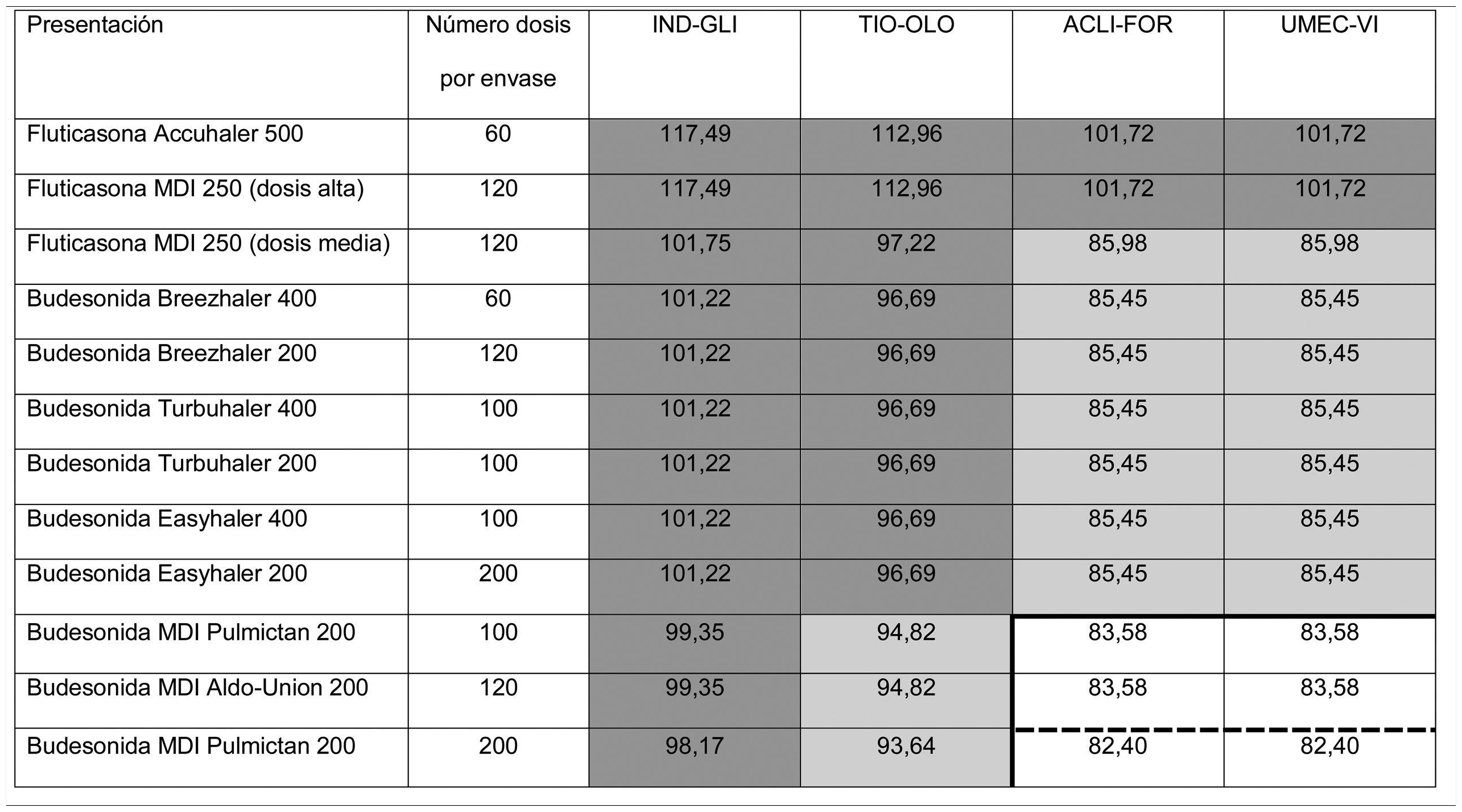

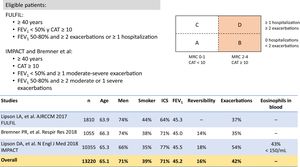

Thus, overall trial data confirms that switching from open triple therapy to FDC confers similar clinical efficacy in the type of patients that were included in these trials. In this setting, then, we must ask what clinical benefits can be obtained from switching from an open triple therapy to an FDC. Three potential benefits can be identified from a review of the literature. Firstly, a smaller number of inhalers has been associated with fewer errors in the management of inhalers,18 which could lead to greater effectiveness. This factor is especially relevant since this treatment includes all 3 families of inhaled drugs available for the treatment of COPD. Consequently, if poor technique leads to critical mistakes in administration, all 3 drugs would be incorrectly administered. Secondly, reducing the number of devices can be expected to result in greater adherence to treatment.19 However, at this point it is important to remember that therapeutic adherence is a complex concept that involves many factors, only 1 of which is the number of devices used.20 In any case, it is important to note that therapeutic adherence is a key element in the clinical interview, and that the professionals who see these patients should take advantage of every contact they have with the health system to reinforce health education, including therapeutic adherence. Thirdly, another potential benefit supporting FDC triple therapy is the price. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the price differences of open triple therapy compared to FDCs. The cost analysis for different combinations of inhaled drug raises some interesting points. First, both FDC triple therapies are more economical than any double FDC therapy. Second, almost all of the open combinations are more expensive than FDCs, with differences in many cases greater than є10 per month. Third, not all open combinations are more expensive than FDCs (Tables 1 and 2), so cost-effectiveness studies are needed to assess the budgetary impact of this change on the health system, taking into account the impact on reduction of exacerbations and, as such, the use of healthcare resources.

Distribution of prices of open triple therapy in comparison with the fixed dose combination, according to the invoicing inventory of the Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare of the Spanish Government, dated May 2019.

Prices are expressed in monthly cost in euros for Spain according to the retail price with value added tax included. Price of FF/UMEC/VI є83.52; BDP/FOR/GB є85.08.

In dark gray, differences with the price of fixed triple therapy of є10 or more; in light gray, less than є10; in white, open triple therapy more economical than fixed.

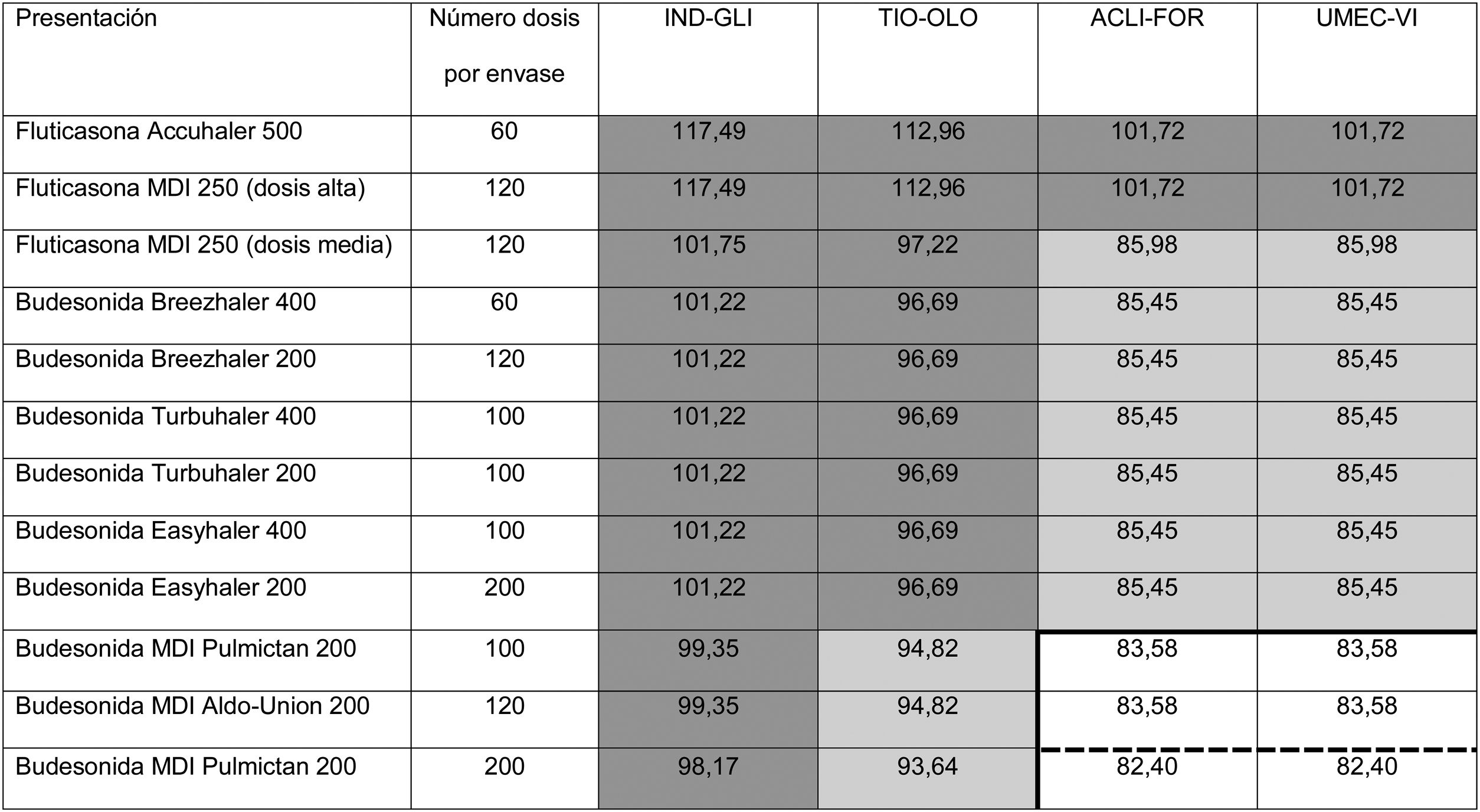

Distribution of prices of open triple therapy in comparison with BDP/FOR/GB, according to the invoicing inventory of the Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare of the Spanish Government, dated May 2019.

ACLI-FOR: aclidinium-formoterol; BDP/FOR/GB: fixed-dose combination of beclomethasone, formoterol, and glycopyrronium; FF/UMEC/VI: fixed-dose combination of fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol; IND-GLI: indacaterol-glycopyrronium; MDI: metered dose inhaler; TIO-OLO: tiotropium-olodaterol; UMEC-VI: umeclidinium-vilanterol.

Prices are expressed in monthly cost in euros for Spain according to the retail price with value added tax included. Fluticasone price calculated for high dose (1,000 µg/day) or average dose (500 µg/day) corticosteroids administered every 12 h. Budesonide price calculated only for average doses (800 µg/day) administered every 12 h. BDP/FOR/GB є85.08. Price of FF/UMEC/VI є83.52. The continuous thick line indicates the combinations that are less expensive than BDP/FOR/GB, and the dashed line indicates the combinations that are less expensive than FF/UMEC/VI.

In summary, the available data indicate that the clinical efficacy of triple therapy FDC is similar to that of the current treatment regimen administered in separate devices with dosing every 12 or 24 h. The safety profile is good and costs are lower than for most open combinations. Moreover, if data on adherence and critical errors in double FDC therapies are similar in triple therapy FDC, it would imply better adherence and fewer errors in inhaler management. Therefore, if a patient with COPD requires triple therapy, it makes sense as a general rule to consider the switch from an open to a fixed regimen. Two pieces of advice must be remembered when this switch is being implemented: the patient must be informed the patient of the change and told that they are going to continue taking 3 drugs but in a single inhalation device, so that they do not have the impression that their treatment is being reduced; and an assessment visit must be scheduled within a few weeks to check the effectiveness and tolerance of the new treatment, as different responses to components of the same drug family have been reported in patients with COPD.21,22

Patients NOT receiving triple therapyAnother scenario involves patients not receiving open triple therapy. Although not all patients included in the triple therapy FDC trials were being escalated (see below), this was the basis on which the clinical trials were designed and the indication that is described in the Summary of Product Characteristics of the marketed FDCs. It is important to remember that these combinations were developed in severely symptomatic patients who presented exacerbations despite treatment with single or double therapy.

It is also important to remember that many patients receiving single or double therapy are well controlled and do not need a change in medication. In the various clinical audits conducted in Spain, treatment was not modified in between 64.8%23 and 77.5%4 of patients evaluated in a routine visit in pulmonology outpatient visits, depending on the study. However, escalation to triple therapy is required in patients who, despite single or double therapy, are still limited by their disease, as reflected in the eligibility criteria of the triple therapy studies (Figs. 2 and 4). Both the methodology and the results of the clinical trials in which the 2 FDCs marketed in Spain, BDP/FOR/GB and FF/UMEC/VI, were developed merit scrutiny.

From a methodological point of view, while the study designs for the 2 FDCs were rather similar, there were some important differences. First, the eligibility criteria varied slightly (Figs. 2 and 4). As a result, patient profiles and severity according to the different clinical and functional parameters were heterogeneous. Although the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score was very similar among all studies (around 20 points for all studies in which it was used), FEV1 was significantly lower (around 36%) in the BDP/FOR/GB studies, compared with the values recorded in the FF/UMEC/VI studies (around 45%). However, in-study rates of moderate/severe exacerbations varied among the trials, regardless of the treatment regimen, with a greater number of events being reported in the IMPACT study13 compared with the rest. Secondly, one of the main differences was the design of the run-in period. Run-in periods are common in clinical trials, and their main objectives are to detect participants who are ineligible or non-compliant, to ensure that participants are in a stable condition, to provide reference values in the same circumstances, to standardize treatment before randomization, to ensure good therapeutic adherence among recruited patients, and to identify any pre-study adverse effects, etc.24,25 All the triple therapy FDC trials had a run-in period of 2 weeks. However, patients in the BDP/FOR/GB studies received the same treatment with double or single treatments during this period, while the FF/UMEC/VI studies allowed the use of previously prescribed triple therapy, specifically 38% of the IMPACT cohort, and 28% of the FULFIL cohort.12,13 As a result, all patients in the BDP/FOR/GB trial were escalated after a run-in period with a similar treatment, but this was not the case for all patients involved the development of FF/UMEC/VI, in whom an abrupt switch in treatment occurred after allocation to the treatment arms.26 Finally, some of these studies had a 6-month follow-up instead of the full year.11,12 As a result, the study populations were different, and raw direct comparisons should be avoided. In the absence of clinical trials with direct comparisons, some meta-analyses are available that may be useful.27–29

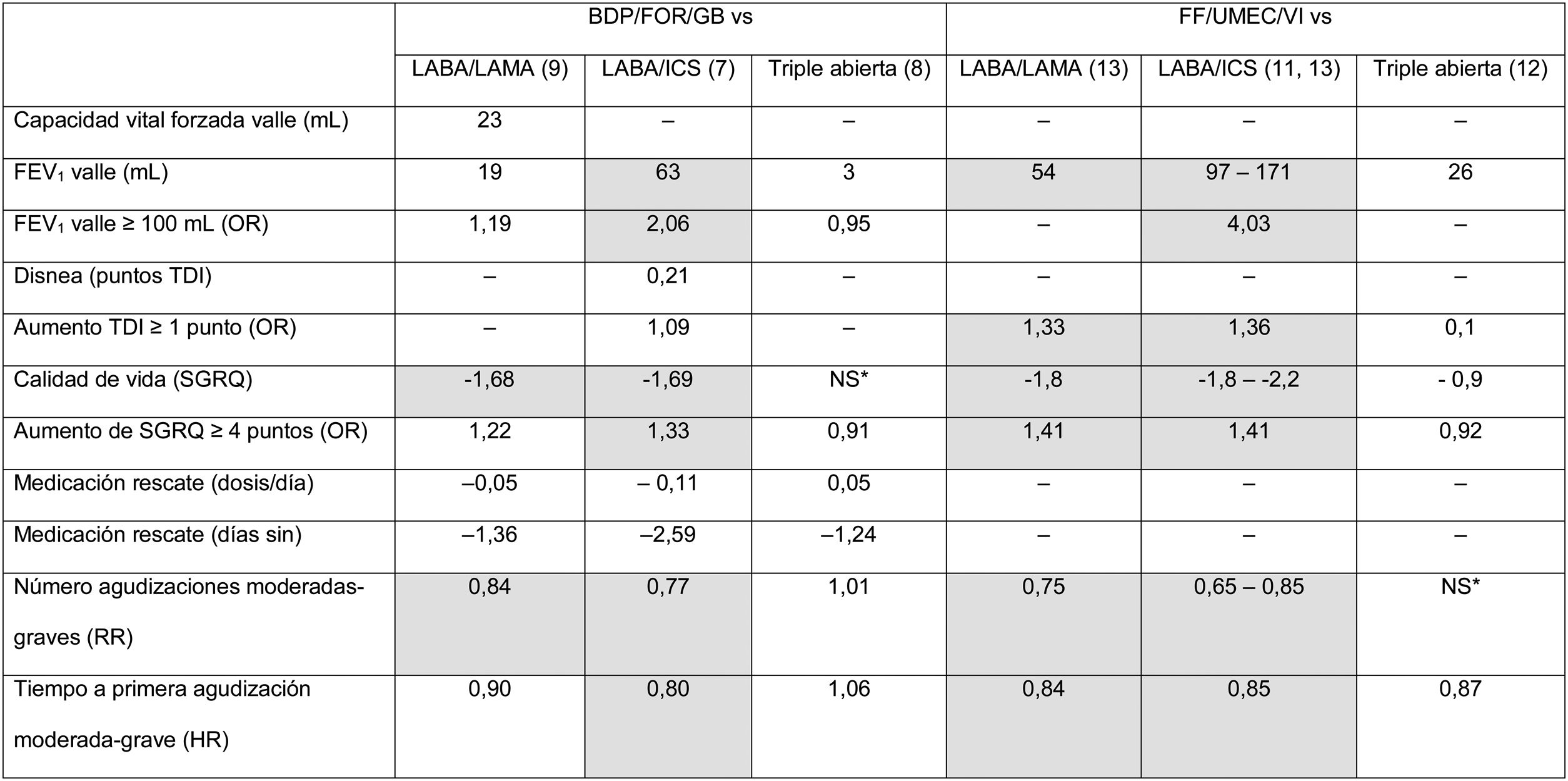

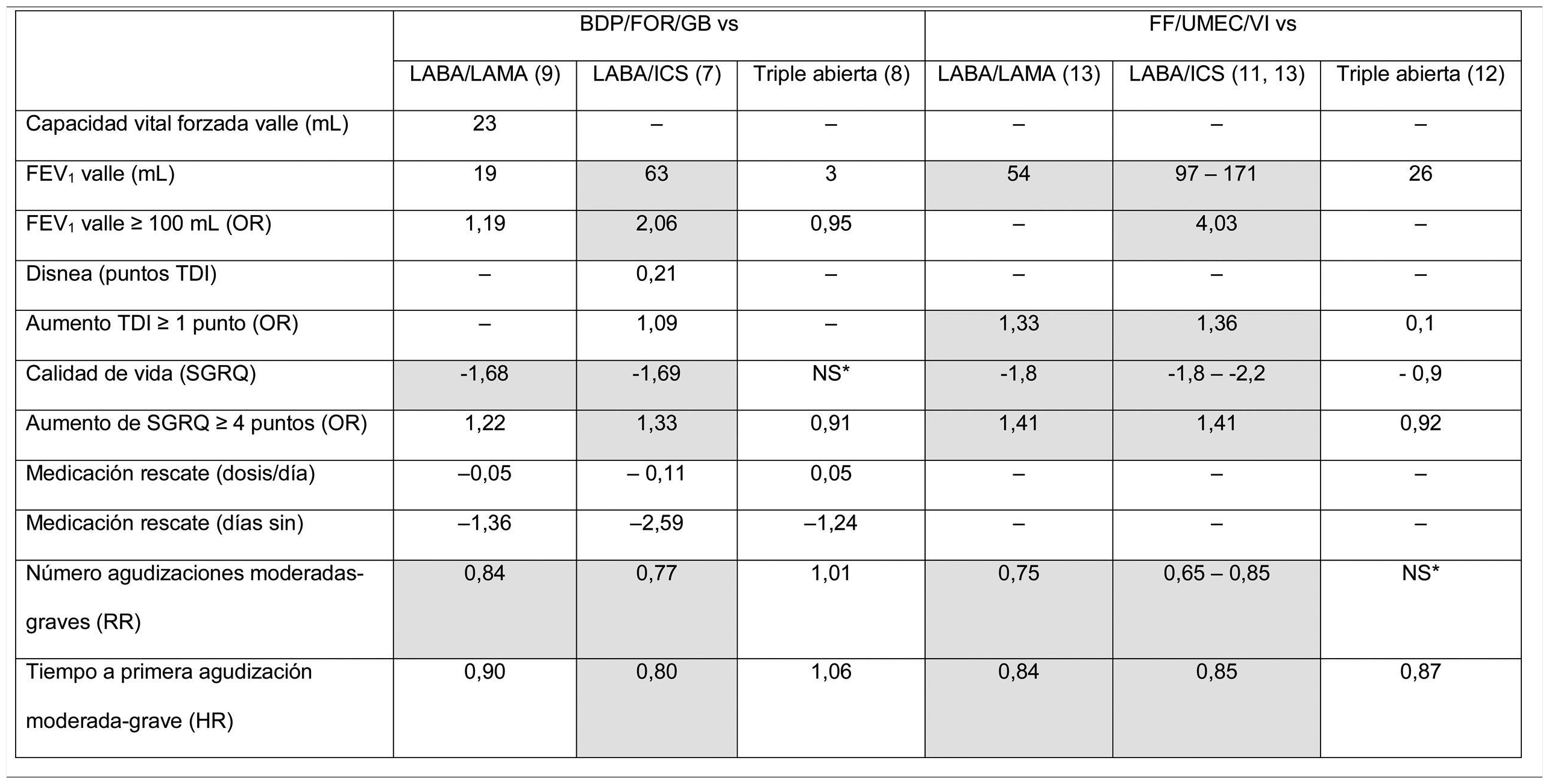

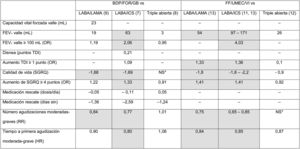

From the point of view of results, clinical benefits in terms of average efficacy are summarized in Table 3, which shows the average differences at the end of the clinical trial for each of the variables for which results are available. A more comprehensive analysis has recently been published.30 These results have been analyzed in several meta-analysis, and the association of triple therapy with clinical efficacy shown in Table 3 is confirmed when pooled data are analyzed.17,31 Some conclusions can be drawn from the analysis and evaluation of these studies. In the first place, there are still many outstanding clinical results that need to be examined. Results, such as morning FEV1 5 min post-dose, peak FEV1, FEV1area under the curve 0−24 h, total lung capacity, functional residual capacity, residual volume, and inspiratory capacity, have not been sufficiently explored or have simply not been analyzed in these trials. Parameters that are of particular interest include the evaluation of dyspnea, which is missing in the vast majority of the studies, and the use of rescue medication, which is not consistently reflected. Secondly, there is considerable variability among the results obtained, among both different FDCs and the same FDC. Variable results can be expected when results of clinical trials that show mean differences between treatment arms are summarized. From a clinical point of view, however, an individualized approach must be taken to improve therapeutic in line with the clinical profile of the patient. In the future, then, real-world studies should be developed and studies must be designed to determine the profile of patients who present a greater therapeutic response to each FDC.

Results of the point estimates as reported in the original clinical trials with triple therapy in a single device.

Data show the average difference achieved at the end of the follow-up for each variable between the triple therapy FDC arm and the comparator for each variable. If more than 1 trial reported these results, the highest and lowest values obtained in all trials that provide this data are shown. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are shown in gray. *NS: no significant differences, with numerical values not specified.

BDP/FOR/GB: fixed-dose combination of beclomethasone, formoterol, and glycopyrronium; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FF/UMEC/VI: fixed-dose combination of fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol; HR: hazard ratio; HRQL: health-related quality of life; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LABA: long-acting ß2-agonists; LAMA: long-acting antimuscarinic agents; NS: no significant differences reported for this data point in any study; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio; SGRQ: St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; TDI: Transition Dyspnea Index.

From the point of view of safety, the proportion of adverse effects was similar among the study groups, and the most common adverse event was worsening chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). With regard to respiratory infections, the trials described a numerical increase in patients with pneumonia who had received an ICS in the IMPACT study, which included 317 (8%) cases receiving triple therapy FDC, 292 (7%) receiving the LABA/ICS combination, and 97 (5%) receiving the LABA/LAMA combination.13 The FULFIL study also showed an increase in these events in the intent-to-treat population, with 19 (2%) events for the triple therapy FDC and 7 (< 1%) for the LABA/ICS combination, but these differences disappeared in the 1-year extension study.11 In the BDP/FOR/GB combination, the TRINITY study reported 28 (3%) cases of pneumonia for triple therapy FDC vs 19 (2%) for tiotropium vs 12 (2%) for open triple therapy.8 The TRIBUTE study9 reported 28 (4%) pneumonias with triple therapy FCD vs 27 (4%) for the LABA/LAMA FDC. The factors that might determine these differences have not yet been identified. It is possible that factors such as the dose, the pharmacological properties of the molecules or their administration in different devices, as well as factors related to individual susceptibility, might modulate the immunosuppressive effect of the different ICS in the airway, ultimately affecting the risk of pneumonia associated with ICS. Clinical studies must be conducted in the future with each FDC to identify patients at risk of developing this complication.

ConclusionsIn summary, the use of triple therapy FDC in Spain presents some challenges in its application in the real world. In patients who are already receiving triple therapy in separate devices, scientific evidence indicates that the clinical efficacy of dosing combined in a single inhalation device is similar. In these cases, patients must be evaluated within a few weeks of the switch to assess their therapeutic response. In patients in whom treatment is escalated from double therapy to triple therapy, data show the mean expected benefits of escalation. Despite the observations reflected here, comparisons between double and triple therapy show improvements in the clinical situation of severe patients with persistent symptoms and exacerbations, in other words, particularly unstable patients who require the best possible treatment. The pharmacological characteristics of each FDC might possibly affect efficacy or safety outcomes in patients, and this question should be addressed in the future. In conclusion, the availability of this new form of treatment provides the clinician with new tools to prescribe a more simple, efficient, and potentially cost-effective treatment in symptomatic patients with frequent exacerbations. Future studies should be conducted to complete the clinical efficacy data with more patient-centered results, and to decisively address individualized patient responses in order to pave the way towards more personalized medicine.

Conflict of interestJLLC has received honoraria in the last 3 years for speaking engagements, scientific consultancy, participation in clinical trials, and preparation of publications from (in alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Esteve, Ferrer, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Menarini, Novartis, Rovi, and Teva.

BAN has received honoraria in the last 3 years for speaking engagements, scientific consultancy, participation in clinical trials, and research funds from (in alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Laboratorios Ferrer, Laboratorios Menarini, Laboratorios Rovi, and Novartis.

LCH has received honoraria in the last 3 years for speaking engagements and participation in clinical trials from (in alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Rovi and Vertex.

LRR declares a collaboration with Laboratorios Ferrer.

The other authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

This document has been prepared by the authors on the basis of clinical studies and their own professional experience, without influence from the pharmaceutical industry.

Please cite this article as: López-Campos JL, Carrasco-Hernández L, Rodríguez LR, Quintana-Gallego E, Bernal CC, Navarrete BA. Implicaciones clínicas del uso de la triple terapia en combinación de dosis fija en EPOC: del ensayo al paciente. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2019.11.011