Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) entails severe symptoms due to blood flow obstruction of the superior vena cava (SVC) towards the right auricle, caused by either extrinsic compression or invasion of the vena cava. Its diagnosis is symptoms-based, the most common symptom being dyspnea, along with findings on physical exploration, especially facial edema and venous distension of the neck and chest wall. Its origin is usually malignant in 90% of cases. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most frequent, followed by small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Other malignant tumors with rare presentation are thymomas, mediastinal germ-cell tumors, mesotheliomas and metastases. SVCS secondary to thymic carcinoma due to intraluminal invasion is rare, as in the patient that we present.

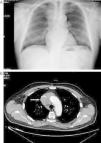

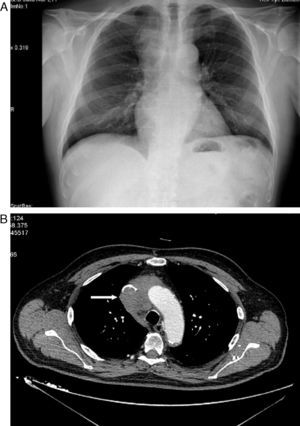

The patient is a 71-year-old male with hypertension, dyslipidemia, a history of atrial fibrillation, anti-coagulation therapy and stable ischemic heart disease. He came to our emergency department due to inflammation of the face, neck and shoulders that had been evolving over the previous 15 days without constitutional syndrome or previous respiratory symptoms. Upon physical examination, BP was 139/81mmHg, 62bpm and normal cardiopulmonary auscultation. Edema of the upper thorax, neck and face were observed. Chest radiology revealed an upper right mediastinal mass (Fig. 1). Therefore, computed tomography (CT) was ordered, which showed a mass in the upper right mediastinum that infiltrated and occluded the SVC (Fig. 1B) and small lower paratracheal and right hilar lymphadenopathies. Hemogram showed slight leukocytosis (10400/μL). Biochemistry, coagulation and tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, PSA, CEA, Ca. 19.9 and β2 microglobulin) were strictly normal. Abdominal–pelvic CT ruled out any alterations in other territories. Treatment was initiated with dexamethasone, which resulted in improved symptoms in the patient, and CT-guided biopsy determined the mass to be thymic carcinoma. According to the Masaoka system, it was classified as stage III–IVb (microscopic invasion of neighboring organs [SVC in this case] and lower paratracheal and right hilar lymph metastasis). The patient was discharged from the hospital with corticosteroids and continued chemotherapy treatment with carboplatin and etoposide. The patient was later administered radiotherapy in order to reduce the size of the tumor mass and achieve surgical resectability, although this was unsuccessful.

SVCS is a pathology associated with malignancy that has a poor prognosis. Etiological possibilities include intrathoracic malignant tumor, which is responsible for 60%–85% of cases. Non-tumor causes represent 15%–40% of cases, depending on the series, and SVC thrombosis is on the rise due to the increasing use of intravascular devices (central venous catheters, pacemakers, etc.). The infectious etiology, which was the protagonist in the pre-antibiotic era, has diminished notably since the appearance of antibiotic therapy. Local vascular post-radiation fibrosis should also be considered. As for the origin of the tumor, the most frequent cause is usually a malignant lung tumor, and NSCLC is the most common (50% of cases), followed by SCLC (25% of cases). Both, together with NHL (10% of cases), constitute approximately 95% of malignant causes.1 Other tumors that are less frequently associated with SVCS are malignant thymic tumors (4%), such as thymoma and thymic carcinoma; the latter represents less than 1% of these tumors. These typical neoplasms of the anterior mediastinum can present at any age in members of either sex. They are aggressive in behavior, as the majority of the cases are associated with the invasion of adjacent organs and/or disseminated disease, as happened in the case that we present. When the said tumors cause SVCS, they usually do so by extrinsic compression, and the vascular invasion seen in our case is rare. It is striking that the search of the literature found only 10 reported cases of SVCS secondary to intraluminal tumor invasion of a thymic tumor.2 This type of tumor is not associated with myasthenia gravis (unlike thymoma) or with other paraneoplastic phenomena. Its presentation usually includes dyspnea, cough, thoracic pain, phrenic nerve paralysis and SVCS.3 Diagnostic confirmation should finally be done with CT-guided biopsy with the aim to histologically catalogue the thymic tumor by means of the Masaoka classification system,4 which is more widely accepted internationally and best correlates with prognosis. As for management, despite there being no randomized clinical assays that define the treatment of these tumors, based on current retrospective studies the treatment of choice both in thymoma as well as in thymic carcinoma consists of surgical resection, which is determined by tumor extension (degree of invasion and/or adherence to contiguous structures). In our case, this was rejected due to the irresectability of the tumor caused by the invasion of the SVC. In this instance, chemotherapy is the best option, followed by radical resection if the response is satisfactory and the clinical stage of the patient permits. This may or may not be associated with later radiotherapy, which is the treatment of choice if irresectability persists. As for the prognosis, based on longer series,5 the most important factors to keep in mind are the state of the disease and tumor histology. Most thymic carcinomas are diagnosed at an advanced phase of the disease (stages III–IV) and, therefore, the prognosis is rather poor, reaching 5-year survival rates of 20%–30%.6

In conclusion, we would like to highlight the fact that when given a patient with SVCS, thymic tumors should be included in the differential diagnosis. Although they are uncommon, early diagnosis and treatment are vital in order to try to obtain a more favorable diagnosis.

Please cite this article as: Rosa Salazar V, et al. Síndrome de vena cava superior como primera manifestación de carcinoma tímico. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48:386–7.