This study assessed vena cava filter (VCF) retrieval rates and factors associated with retrieval failure in a single center cohort.

MethodsWe conducted an observational retrospective cohort study. The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients whose VCF was retrieved. We performed logistic regression to identify variables associated with retrieval failure.

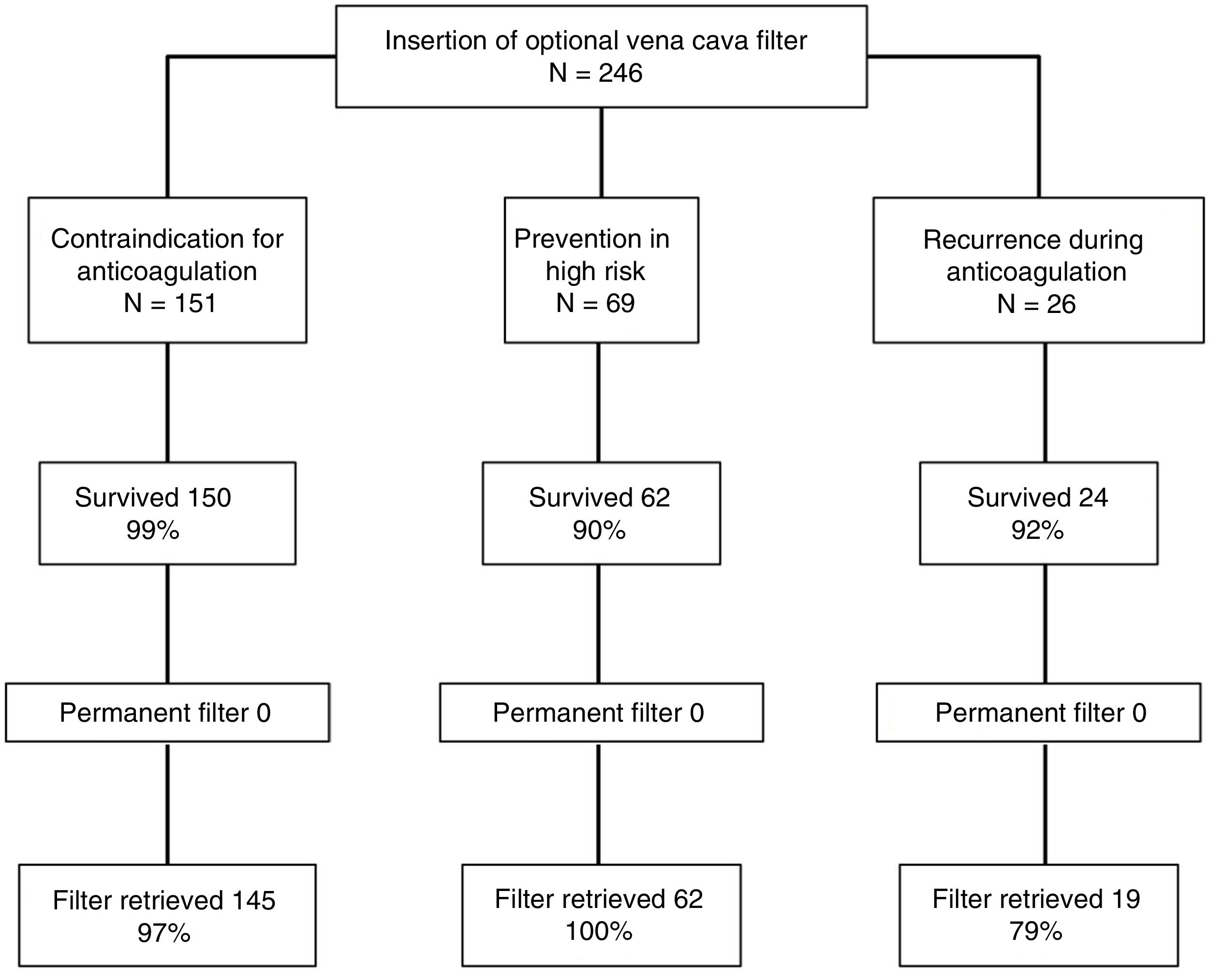

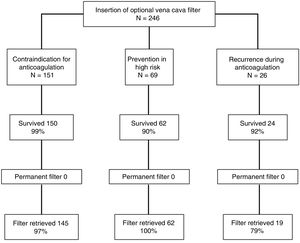

ResultsDuring the study period, 246 patients received a VCF and met the eligibility requirements to be included in the study; 151 (61%) patients received a VCF due to contraindication to anticoagulation, 69 (28%) patients had venous thromboembolism (VTE) and a high risk of recurrence, and 26 (11%) patients received a filter due to recurrent VTE while on anticoagulant therapy. Of 236 patients who survived the first month after diagnosis of VTE, VCF was retrieved in 96%. Retrieval rates were significantly lower for patients with recurrent VTE while on anticoagulation, compared with patients with contraindication to anticoagulation or patients with a high risk of recurrence (79% vs 97% vs 100%, respectively; P<0.01). Mean time to retrieval attempt was significantly associated with retrieval failure (137.8±65.3 vs 46.3±123.1 days, P<0.001).

ConclusionsIn this single center study, VCF retrieval success was 96%. A delay in the attempt to retrieve the VCF correlated significantly with retrieval failure.

El objetivo de este estudio fue calcular el porcentaje de filtros de vena cava inferior (FVCI) opcionales finalmente recuperados y las variables asociadas a la imposibilidad para su recuperación en una cohorte de pacientes con enfermedad tromboembólica venosa (ETEV).

MétodosSe realizó un estudio observacional retrospectivo. La variable principal fue el porcentaje de FVCI recuperables finalmente extraídos. Se realizó regresión logística para identificar las variables asociadas al fracaso de la recuperación del FVCI.

ResultadosDurante el período de estudio se implantaron 246 FVCI, 151 (61%) en pacientes con contraindicación para la anticoagulación, 69 (28%) para la prevención de tromboembolia de pulmón en pacientes de alto riesgo y 26 (11%) en pacientes con recurrencia trombótica a pesar de anticoagulación correcta. De los 236 pacientes que sobrevivieron el primer mes, se intentó la retirada del FVCI en todos ellos y fue posible en 226 pacientes (96%). La tasa más baja de retirada se produjo en el grupo de pacientes con recurrencias trombóticas mientras estaban anticoagulados, comparados con los pacientes con contraindicación para anticoagular y con los pacientes de alto riesgo (79 vs 97 vs 100%, respectivamente; p<0,01). El tiempo de retraso hasta el intento de retirada fue significativamente mayor para los pacientes a los que no se les pudo retirar el FVCI (137,8±65,3 días) comparados con los pacientes a los que se les pudo retirar el FVCI (46,3±123,1 días; p<0,001).

ConclusionesEn este estudio de un único centro se consiguió la retirada del FVCI en el 96% de los casos. El retraso en el intento de retirada del FVCI se asoció de manera significativa al fracaso en su extracción.

Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality.1,2 The accepted treatment for hemodynamically stable patients is anticoagulation, while reperfusion treatments (e.g., fibrinolysis) are reserved for unstable patients in the absence of contraindications for use.3,4 Earlier studies have shown that, despite their efficacy in the prevention of pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), inferior vena cava (IVC) filters increase the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and do not improve survival in patients with PTE.5,6 For this reason, clinical practice guidelines do not recommend the use of these devices in the first-line treatment of VTE.4,7 The major indication for IVC filters is contraindication for anticoagulation (evidence grade IB).3 However, while the use of these devices has plateaued or even decreased in Europe,8 it has gradually increased in the United States.9,10

Most studies published to date refer to permanent IVC filters or to older models. Clinical evidence on the efficacy and safety, indications, follow-up, and retrieval time of optional IVC filters is limited.11 Even when these devices are retrievable, they are withdrawn in less than 50% of recipients,12 and removal rates are inversely related to the time that the IVC filter remains in place.11 Numerous complications associated with permanent IVC filter placement have been described,13,14 prompting the Food and Drug Administration to issue several alerts and recommendations for the retrieval of these devices as soon as they are no longer necessary.14

The aim of this study was to analyze the baseline characteristics of a cohort of patients who received a retrievable IVC filter for the prevention or treatment of VTE. We also calculated the percentage of IVC filters retrieved, and explored complications associated with their placement and removal, and variables associated with failure to retrieve.

MethodDesignThis was a retrospective observational study to analyze the baseline characteristics and progress of a patient cohort with a diagnosis of VTE who received a retrievable IVC filter. All patients or their legal representatives gave their signed informed consent in accordance with the requirements of the local ethics committee.

Patients and Selection CriteriaAll patients consecutively diagnosed with acute symptomatic PTE or VTE in the Minimally Invasive Image-Guided Surgery Unit of the Hospital Universitario Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza (Spain), between January 2006 and March 2016, were included.

The diagnosis of PTE was confirmed by computed tomography (CT) angiography findings of a partial intraluminal defect surrounded by contrast medium or complete occlusion of a pulmonary artery in 2 consecutive CT slices.15 PTE was diagnosed by ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy in patients with a high probability of PE according to PIOPED criteria16 (at least 1 segmental perfusion defect or 2 subsegmental defects with normal ventilation), or on the basis of an inconclusive scintigraphy and positive diagnostic ultrasound of the lower limbs in cases with clinical suspicion of PTE. DVT was diagnosed when compression ultrasound revealed a compressibility defect of the lumen.17

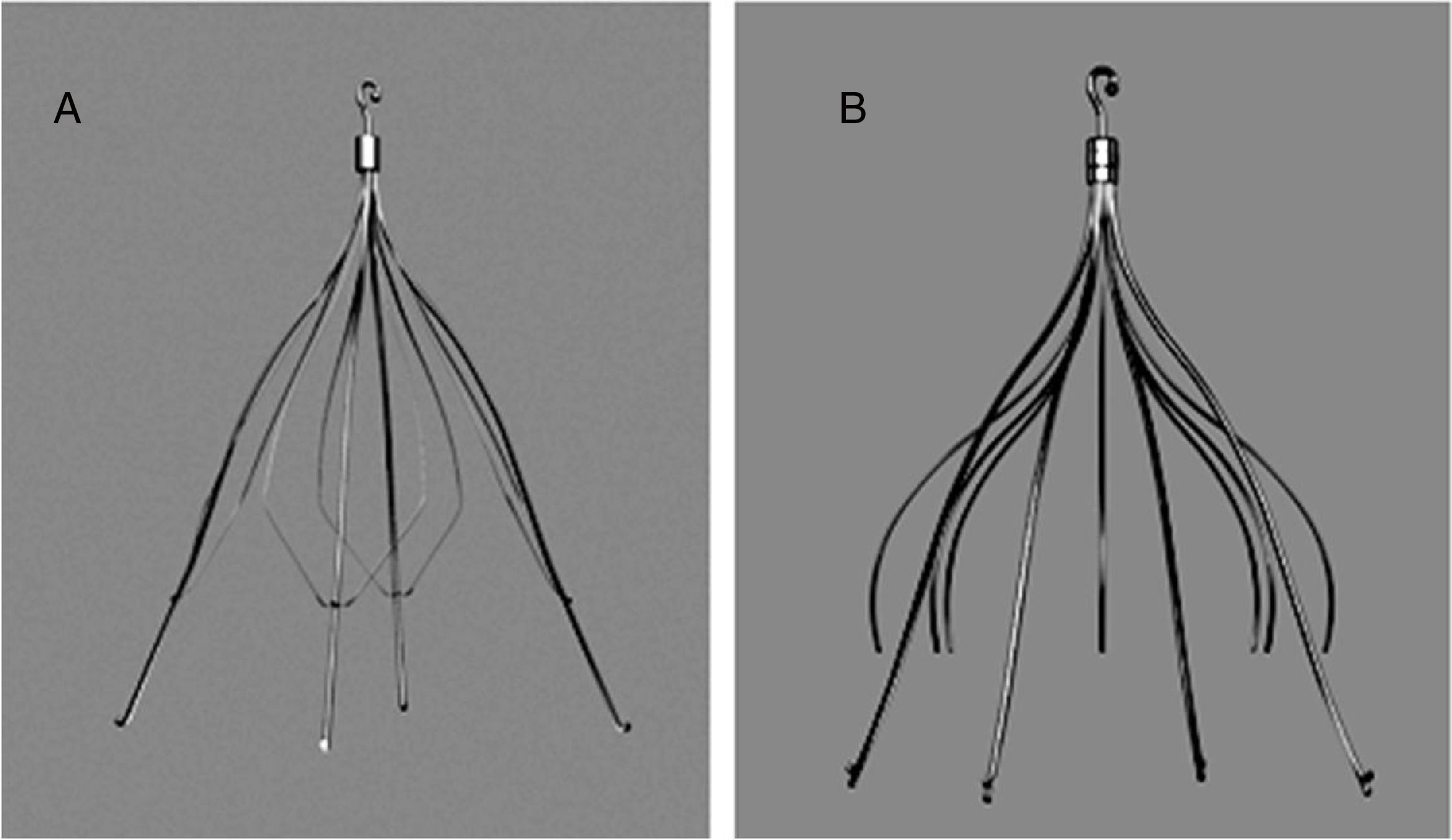

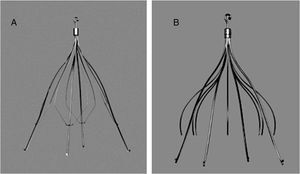

Filter Implantation and RemovalBoth retrievable IVC filters used in the study (Gunther® and Celect®) were manufactured by Cook Medical (Bloomington, Indiana, US) (Fig. 1).

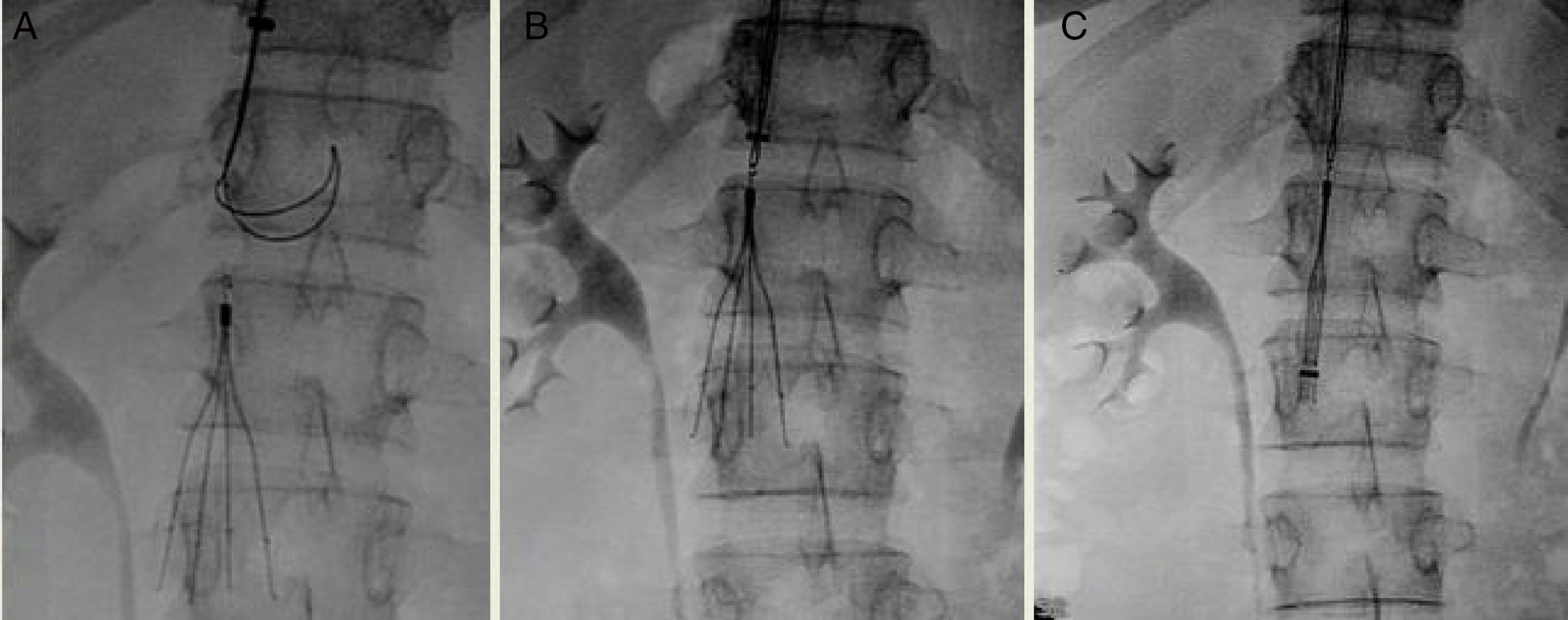

Both filters can be inserted via the femoral or the jugular vein using a 7-French (Fr) introducer sheath. The device should be retrieved via the jugular vein, using an 11-Fr sheath. When removal of the IVC filter was indicated, a cavogram was performed to assess the existence of complications.18 In our series, anticoagulation was not discontinued for the procedure, the retrieval set recommended by the manufacturer was used as the first option, and the approach of choice was the right jugular route (Fig. 2).

If IVC filter removal was not achieved, the attempt was repeated using a different strategy (e.g., with simultaneous femoral and jugular access, balloons, ligatures, forceps, or excimer laser).19,20 After 3 failed attempts, the IVC filter was left as permanent, and the patient continued to receive coagulation.

Study EpisodesThe primary evaluation parameter was defined as the percentage of retrievable IVC filters finally removed. Secondary parameters were the percentage of complications associated with the placement or removal of the IVC filter, and all-cause death during the first year following IVC filter placement.

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range), as appropriate, and were compared with the Student's t test or the Mann–Whitney U test for asymmetric data. Categorical variables were represented as percentages and compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, if necessary.

A bivariate analysis including patient demographic and clinical variables was performed to identify the characteristics associated with failure to remove the IVC filter. All variables associated with a significance level of P<0.1 were included in a multivariate logistic regression model. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Data were analyzed using the SPSS 15.0 program (Chicago, Illinois, United States).

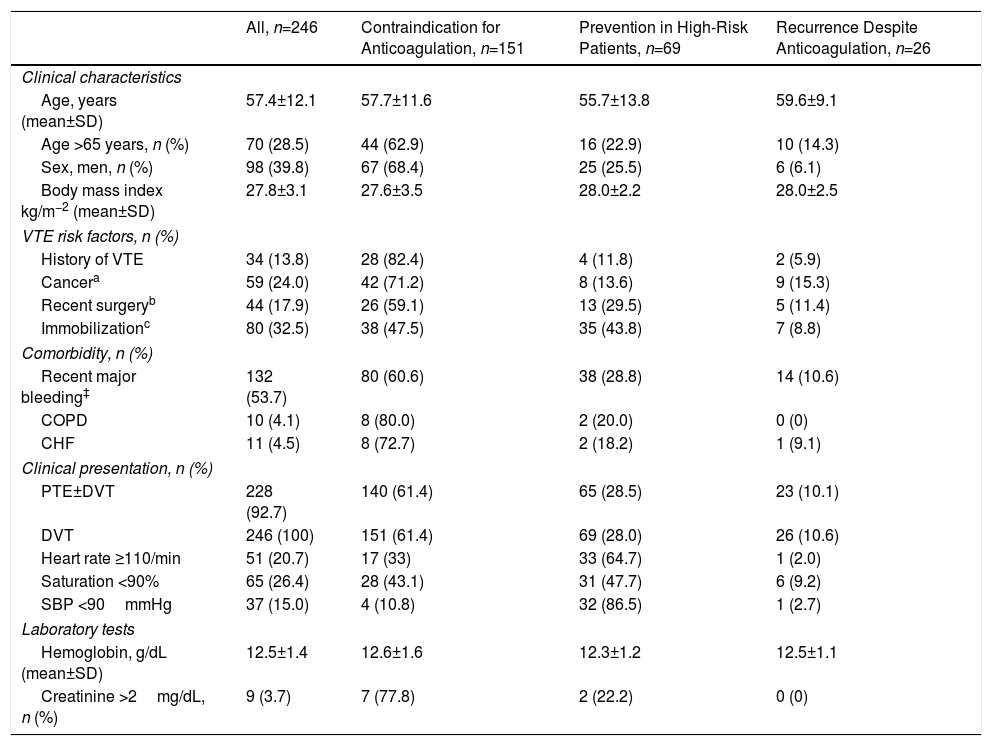

ResultsDuring the study period, 246 IVC filters were implanted in 246 patients. In total, 119 patients (48%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 42%–55%) received an IVC filter due to contraindication for anticoagulation; 32 (13%; 95% CI: 9.1%–18%) for hemorrhagic complication during anticoagulation; 39 (16%; 95% CI: 12%–21%) patients with unstable PTE and DVT received an IVC filter for prevention of recurrent PTE during treatment with thrombectomy and fibrinolysis; IVC filter was indicated in 30 patients (12%; 95% CI: 8.4–17%) with DVT for the prevention of PTE (iliocaval thrombus, severe COPD, poor respiratory reserve), and in 26 patients (11%; 95% CI: 7.0%–15%), IVC filter was indicated for recurrent thrombosis despite appropriate anticoagulation. Mean age of patients was 57 years (standard deviation [SD] 12), and 40% were men. General patient characteristics according to indications for IVC filter placement are listed in Table 1. In total, 95 patients received anticoagulants during the first month after the diagnosis of VTE. After contraindications for anticoagulation were resolved, all patients continued to receive anticoagulants for a mean of 8.0±3.7 months (range: 6–48 months).

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics by Filter Indication.

| All, n=246 | Contraindication for Anticoagulation, n=151 | Prevention in High-Risk Patients, n=69 | Recurrence Despite Anticoagulation, n=26 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 57.4±12.1 | 57.7±11.6 | 55.7±13.8 | 59.6±9.1 |

| Age >65 years, n (%) | 70 (28.5) | 44 (62.9) | 16 (22.9) | 10 (14.3) |

| Sex, men, n (%) | 98 (39.8) | 67 (68.4) | 25 (25.5) | 6 (6.1) |

| Body mass index kg/m−2 (mean±SD) | 27.8±3.1 | 27.6±3.5 | 28.0±2.2 | 28.0±2.5 |

| VTE risk factors, n (%) | ||||

| History of VTE | 34 (13.8) | 28 (82.4) | 4 (11.8) | 2 (5.9) |

| Cancera | 59 (24.0) | 42 (71.2) | 8 (13.6) | 9 (15.3) |

| Recent surgeryb | 44 (17.9) | 26 (59.1) | 13 (29.5) | 5 (11.4) |

| Immobilizationc | 80 (32.5) | 38 (47.5) | 35 (43.8) | 7 (8.8) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Recent major bleeding‡ | 132 (53.7) | 80 (60.6) | 38 (28.8) | 14 (10.6) |

| COPD | 10 (4.1) | 8 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0) |

| CHF | 11 (4.5) | 8 (72.7) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (9.1) |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | ||||

| PTE±DVT | 228 (92.7) | 140 (61.4) | 65 (28.5) | 23 (10.1) |

| DVT | 246 (100) | 151 (61.4) | 69 (28.0) | 26 (10.6) |

| Heart rate ≥110/min | 51 (20.7) | 17 (33) | 33 (64.7) | 1 (2.0) |

| Saturation <90% | 65 (26.4) | 28 (43.1) | 31 (47.7) | 6 (9.2) |

| SBP <90mmHg | 37 (15.0) | 4 (10.8) | 32 (86.5) | 1 (2.7) |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (mean±SD) | 12.5±1.4 | 12.6±1.6 | 12.3±1.2 | 12.5±1.1 |

| Creatinine >2mg/dL, n (%) | 9 (3.7) | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; IVC filter: inferior vena cava filter; PTE: lung thromboembolism; SD: standard deviation; SBP: systolic blood pressure; VTE: venous thromboembolism.

A history of VTE (P=0.02), active cancer or current cancer treatment (P=0.01), and medical immobilization (P<0.01) was significantly more frequent in patients who received IVC filters due to contraindication for anticoagulation. Patients who received an IVC filter for prevention of fatal PTE had a higher incidence of tachycardia (heart rate≥110bpm/min), desaturation (saturation <90%), and hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90mmHg), compared with patients who received the device for other indications (P<0.001 for all comparisons).

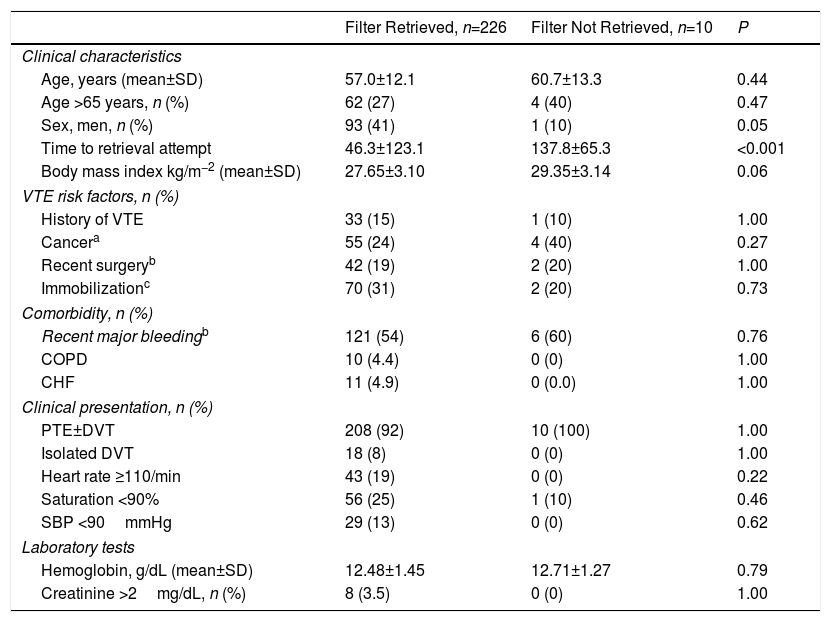

Ten patients died during the first month of follow-up (4.1%, 95% CI: 2.0%–7.3%), all due to PTE: 7 in the high-risk group who received an IVC filter for PTE prevention; 2 in the group who received an IVC filter for recurrent thrombosis during anticoagulation, and 1 in the group with contraindication for anticoagulation. IVC filter retrieval was attempted in all the 236 patients who survived, and was successful in 226 (96%; 95% CI: 92%–98%) (Fig. 3). After 1 year of follow-up, the lowest rate of retrieval was observed in patients who had thrombotic recurrences while receiving anticoagulants, compared to the high-risk group and to the recurrence group (79% vs 97% vs 100%, respectively; P<0.01). Mean time (SD) until an attempt was made to retrieve the IVC filter was 49.8±122.5 days, with a median of 32 days and a range of 24–1865 days. Mean time (SD) to IVC filter retrieval attempt was 54.6±152.7 days in patients with contraindications for anticoagulation, 35.0±13.1 days in high-risk patients, and 58.1±39.2 days in patients with recurrent thrombosis during anticoagulation (P=0.37).

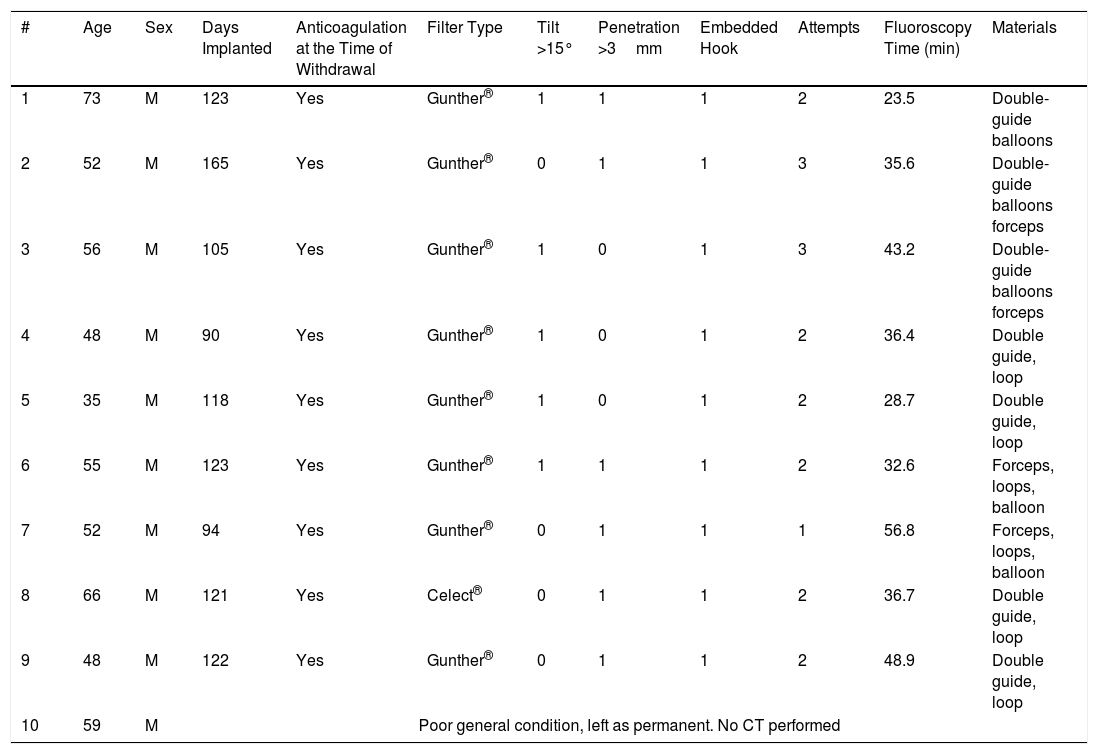

Of the 226 IVC filters retrieved, 187 (83%; 95% CI: 77–87%) were extracted at the first attempt, 38 (17%) required 2 attempts and 1 (0.4%) required 3 attempts. Of these, 23 (10%) IVC filters presented a tilt of >15°, 9 (4.0%) presented venous wall penetration >3mm, and 3 (1.3%) presented a thrombus >1cm within the filter. Ten optional IVC filters (4.4%) were not retrieved: 9 were impossible to retrieve despite several attempts and various maneuvers, and the procedure was impossible in 1 case due to the poor status of the patient. The 9 IVC filters that could not be retrieved after several attempts demonstrated the following features on CT and phlebography performed before the procedure: >15° tilt in the IVC axis (5 cases, 56%), venous wall penetration >3mm (6 cases, 67%), and penetration of the retrieval hook in the IVC wall (9 cases, 100%) (Table 2). Patients in whom the IVC filter could not be retrieved were mostly women, and the delay before the retrieval attempt was significantly longer (137.8±65.3 vs 46.3±123.1 days, P<0.001) than in patients in whom IVC filter retrieval was successful (Table 3).

Characteristics of the 10 Patients in Whom the Filter Could Not be Retrieved.

| # | Age | Sex | Days Implanted | Anticoagulation at the Time of Withdrawal | Filter Type | Tilt >15° | Penetration >3mm | Embedded Hook | Attempts | Fluoroscopy Time (min) | Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73 | M | 123 | Yes | Gunther® | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 23.5 | Double-guide balloons |

| 2 | 52 | M | 165 | Yes | Gunther® | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 35.6 | Double-guide balloons forceps |

| 3 | 56 | M | 105 | Yes | Gunther® | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 43.2 | Double-guide balloons forceps |

| 4 | 48 | M | 90 | Yes | Gunther® | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 36.4 | Double guide, loop |

| 5 | 35 | M | 118 | Yes | Gunther® | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 28.7 | Double guide, loop |

| 6 | 55 | M | 123 | Yes | Gunther® | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 32.6 | Forceps, loops, balloon |

| 7 | 52 | M | 94 | Yes | Gunther® | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 56.8 | Forceps, loops, balloon |

| 8 | 66 | M | 121 | Yes | Celect® | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 36.7 | Double guide, loop |

| 9 | 48 | M | 122 | Yes | Gunther® | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 48.9 | Double guide, loop |

| 10 | 59 | M | Poor general condition, left as permanent. No CT performed | ||||||||

CT: computed tomography; F: female; M: male.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics by Filter Retrieval or No Retrieval.

| Filter Retrieved, n=226 | Filter Not Retrieved, n=10 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 57.0±12.1 | 60.7±13.3 | 0.44 |

| Age >65 years, n (%) | 62 (27) | 4 (40) | 0.47 |

| Sex, men, n (%) | 93 (41) | 1 (10) | 0.05 |

| Time to retrieval attempt | 46.3±123.1 | 137.8±65.3 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index kg/m−2 (mean±SD) | 27.65±3.10 | 29.35±3.14 | 0.06 |

| VTE risk factors, n (%) | |||

| History of VTE | 33 (15) | 1 (10) | 1.00 |

| Cancera | 55 (24) | 4 (40) | 0.27 |

| Recent surgeryb | 42 (19) | 2 (20) | 1.00 |

| Immobilizationc | 70 (31) | 2 (20) | 0.73 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||

| Recent major bleedingb | 121 (54) | 6 (60) | 0.76 |

| COPD | 10 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| CHF | 11 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | |||

| PTE±DVT | 208 (92) | 10 (100) | 1.00 |

| Isolated DVT | 18 (8) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Heart rate ≥110/min | 43 (19) | 0 (0) | 0.22 |

| Saturation <90% | 56 (25) | 1 (10) | 0.46 |

| SBP <90mmHg | 29 (13) | 0 (0) | 0.62 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (mean±SD) | 12.48±1.45 | 12.71±1.27 | 0.79 |

| Creatinine >2mg/dL, n (%) | 8 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; SBP: systolic blood pressure; SD: standard deviation; PTE: lung thromboembolism; VTE: venous thromboembolism.

During the follow-up period, 2 IVC filters migrated (0.8%; 95% CI: 0.1%–3.0%); 14 IVC filters developed thrombosis (5.9%; 95% CI: 3.3%–9.8%), mostly (9 of 14, 64%) in patients who could not receive anticoagulation, and 5 jugular hematomas occurred (2.1%; 95% CI: 0.7%–4.9%). Twenty-one patients died (21 of 246, 8.5%, 95% CI 5.4%–13%) during the first year of follow-up.

DiscussionIn this study of patients seen in a single expert interventional radiological center, retrievable IVC filters could be recovered in 96% of cases. The best retrieval rate was achieved with IVC filters indicated for prevention in high-risk patients, and the poorest was recorded in patients with recurrent thrombosis despite anticoagulation. Delay in the attempt to retrieve the IVC filter was significantly associated with failure of the procedure.

In our series, 96% of the IVC filters were retrieved. This figure is similar to that of a recent study in 628 patients who had received an optional IVC filter. In this series, 576 IVC filters (92%) were retrieved, and the complication rate was low.21 However, the results of a US cohort of 54766 patients who received an IVC filter suggest that recovery rates may be significantly lower (18%).22 A systematic review of 37 studies that included a total of 6834 patients found a retrieval rate of 34%.12 Discrepancies in these results may be associated with study design: highly experienced centers reported high retrieval rates, while low rates were found in non-selected cohort studies.

According to one study, the optimal time for IVC filter retrieval ranges between 29 and 54 days after insertion.23 In our study, the mean time until the retrieval attempt was 46 days for patients whose IVC filter was finally removed, and 138 days for patients with unsuccessful retrieval. These results underline the importance of removing the IVC filter as soon as possible after placement. Although the real incidence of complications associated with the IVC filter (breakage, migration, inferior vena cava perforation or obstruction by extensive thrombosis) is unknown, complications appear to be rare in the first 30 days after insertion, and increase with the passage of time.10 Our series confirms these findings.

In this study, IVC filters were placed due to contraindication for anticoagulation in 61% of patients. The potential complications associated with the use of the IVC filter and failure to retrieve the device in a varying percentage of cases suggests the need to individualize the indications for insertion. There is consensus on the benefit of IVC filters in patients with VTE and contraindication for anticoagulation.3,7 In a study of 688 patients with VTE with a high risk of bleeding included in the RIETE registry, IVC filter placement significantly reduced PTE mortality in the first 30 days of follow-up (1.7% vs 4.9%: P=0.03).24 However, the evidence in patients with acute PTE and high risk of recurrence does not support the use of IVC filters. Mismetti et al.25 randomized 399 patients with acute PTE and high risk of recurrence (concomitant DVT and at least 1 of the following criteria: age >75 years, cancer, chronic heart failure, ischemic stroke with limb paresis in the last 6 months, iliocaval or bilateral DVT, or at least 1 sign of right ventricular dysfunction or myocardial lesion) to receive anticoagulation plus IVC filter or anticoagulation alone. During the 3-month follow-up, recurrent PTE occurred in 3% of patients who received an IVC filter, and in 1.5% of patients who did not (relative risk with IVC filter: 2.00; 95% CI: 0.51–7.89; P<0.50). In patients with recurrent thrombosis despite appropriate anticoagulation, the American College of Chest Physicians recommends low molecular weight heparin,3 while the European Society of Cardiology recommends IVC filter placement.7 One study using data from the RIETE registry found that IVC filter placement in patients with recurrent PTE despite anticoagulation decreased the risk of 30-day all-cause death by 94%, although no beneficial effect was observed in patients with recurrent DVTs.26

Our study has limitations. This is a retrospective analysis of the experience of a single expert interventional center, so the rate of successful retrievals may be overestimated. Moreover, the number of patients in whom IVC filter retrieval was small, making it impossible to evaluate the independent association between clinical variables and retrieval failure.

In conclusion, early withdrawal of optional IVC filters is feasible in most patients when performed in an experienced hospital. Physicians should carefully select patients who will benefit from the placement of an optional IVF filter, and retrieval should be attempted as soon as the indication for the device is resolved.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: de Gregorio MA, Guirola JA, Serrano C, Figueredo A, Kuo WT, Quezada CA, et al. Éxito en la recuperación de filtro de vena cava inferior opcional: Análisis de 246 pacientes. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:371–377.