Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology. Though pulmonary involvement is reported in the majority of sarcoidosis patients, extrapulmonary disease is seen in up to 50%. Patients may be asymptomatic, present with insidious symptoms such as malaise, fever, and dyspnea or organ-specific involvement (most commonly skin, eye, liver, heart and osteoarticular system).1 It is a disease described in every ethnic group with a varying incidence of female preponderance. The northern European countries and black Americans have the highest incidence (50–60 and 35.5 per 100,000 people, respectively).2

The diagnosis is established by the combination of a suggestive clinical syndrome such as the Löfgren's syndrome (arthritis, erythema nodosum and bilateral hilar lymph nodes) and radiologic findings, supported by histologic identification of noncaseating granulomas.3

Bone involvement is reported in up to 13% of sarcoidosis patients, but may be underdiagnosed as specific studies are not routinely performed. Historically, it affects more frequently appendicular bones and joints of the hands and feet, but axial disease has been rarely described. Bone lesions are typically described as cystic with cortical bone involvement, although sclerotic and lytic have also been reported.4

In this report, the authors describe a case of systemic sarcoidosis presenting as vertebral lytic fracture and discuss clinical, diagnosis and therapeutic approaches, namely the importance of biological therapy in refractory cases.

A 59-year-old healthy female was admitted for investigation of a lumbar fracture (L2) after a low energy trauma. She presented with one year of gradually worsening generalized bone pain, fatigue, and mild dyspnea. She was a non-smoker and had no previous infections, environmental exposure or significant travel history. No significant family history was determined. Apart from lower back non-radiating pain, physical examination was unremarkable, with no skin lesions or palpable lymph nodes.

Laboratory testing showed mild hypocalcemia of 8.4mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 34mm/h and gamma monoclonal band on serum protein electrophoresis (19.8g/dL). Computed tomography (CT) scan of the lumbar spine revealed L2 fracture and L3, S2 and S3 lytic lesions.

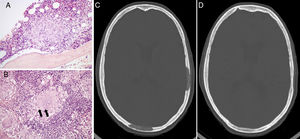

Etiological investigation was initiated with a CT scan that further revealed multiple lytic lesions of the skull (Fig. 1C), sternum, ribs, hip bone and cervical and thoracic vertebrae, associated with cervical, mediastinal, hilar, abdominal and pelvic lymph nodes (<2cm) as well as nodular infiltration of the lungs and liver (<1cm).

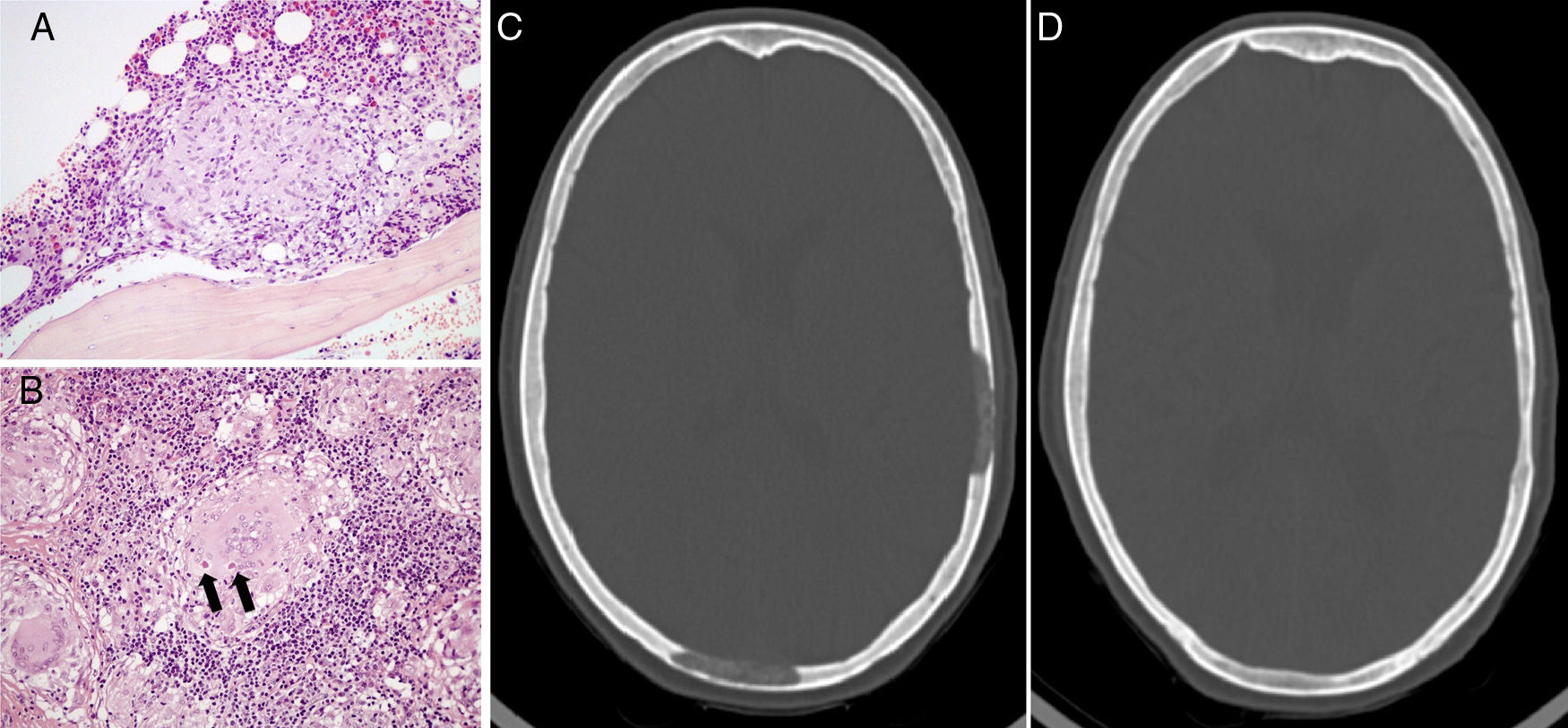

(A) An epithelioid granuloma is observable next to a bone trabecula of the iliac crest, amidst the hematopoietic medullary tissue. (B) A multinucleated giant cell is shown (granuloma) in the tonsil tissue, with two dense concretions suggestive of Schaumann bodies within its cytoplasm. (C) Lytic lesions of the skull before treatment. (D) Total regression of the lytic lesions after treatment with Infliximab.

Neoplastic etiology was excluded after colonoscopy, endoscopy, mammogram, thyroid ultrasound and complete gynecological and dermatological evaluation. Biopsies of cervical lymph nodes, nasopharyngeal airway, tonsils and hip bone showed chronic inflammatory tissue with granulomas (Fig. 1A), some of which with caseum. There were remnants of an asteroid body and a multinucleated giant cell with two dense concretions suggestive of Schaumann bodies within its cytoplasm in the tonsil tissue (Fig. 1B).

Blood cultures, infectious and autoimmune serologies excluded other causes of systemic granulomatous disease. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) revealed high lymphocytes (19%) in cellular analysis with technically indeterminable CD4/CD8 ratio. The diagnosis of tuberculosis suggested by caseating granulomas was refuted by negative Interferon Gamma Release Assay and mycobacterial and microbiological cultures of the BAL. The final diagnosis came to be sarcoidosis with important bone and lymph node involvement.

Her respiratory function tests were normal and her six-minute walk test was unremarkable, apart from the initial and final modified dyspnea Borg scale (1 very slight and 2 slight, respectively).

Treatment was started with 40mg of prednisone and, after 5 months of treatment, there were no clinical or radiological improvements. It was then associated methotrexate 15mg weekly and after 3 months the patient showed better physical tolerance and less generalized bone pain. In spite of clinical improvement, she was proposed to start treatment with Infliximab due to the growth of the lytic bone lesions combined with rising of angiotensin-converting enzyme value (58–92U/L). After 11 months of biological therapy, the patient became asymptomatic and had regression of most lytic bone lesions (Fig. 1D), mediastinal lymph nodes and lung nodules. She maintains treatment with increasing radiological improvements and no adverse reactions were recorded.

Involvement of vertebrae and skull in sarcoidosis has been rarely reported and vertebral fracture after a low energy trauma was never described as the first manifestation of sarcoidosis.

The rarity of axial involvement may be explained by the fact that bone sarcoidosis is usually asymptomatic. Its diagnosis may be suggested by radiologic techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), which may not be easily available. Furthermore, these studies still lack specificity in distinguishing sarcoidosis from other diagnosis, mainly metastatic disease.5 In our patient, the generalized lymph nodes and lytic bone lesions demanded, therefore, histological confirmation.

Sarcoidosis is frequently a chronic disease with multiple available treatments yet steroids are still the main treatment. In severe cases, the use of cytotoxic agents has been shown to be beneficial, such as methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and hydroxychloroquine.

It has been described that patients with bone sarcoidosis are frequently associated with multi-organ disease and poor prognosis, usually with decreased response to steroid treatment, as seen in our patient.6

In recent studies, there has been an increase in evidence of the efficacy of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antagonists in the treatment of patients with pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis, such as Infliximab and Adalimumab. They stop granulomatous inflammation, by acting against the macrophages of patients with sarcoidosis that release TNF-α, which is believed to be involved in the development of granulomas. The use of TNF-α antagonists is important by allowing the reduction of steroid effective dose, its cumulative toxicity and side-effects. They have also been proven to be effective in refractory cases, that are associated with higher levels of TNF-α in BAL.7

In our patient, the use of Infliximab was essential in clinical and organ involvement improvement, mainly the axial bone lesions, such as the skull and vertebrae, validating its efficacy in severe refractory cases.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Rita Luís for her help in the interpretation of the histological images.