Pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma is an uncommon lung disease. Its etiopathogenesis is unknown, although it could be associated with an autoimmune or previous infectious process. The definitive diagnosis is provided by the histopathologic study of the lesion. We describe the case of a patient with a history of tuberculosis and with a pulmonary nodular lesion that was determined to be a metastatic neoplastic process.

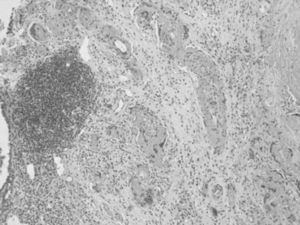

Our patient is a 66-year-old male who smoked a pack a day. His pathological history of interest included childhood tuberculosis and necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenitis in a supraclavicular lymph node in 1997 with a PCR that was negative for mycobacteria. The patient presently came to our hospital due to respiratory difficulty and a feverish syndrome that had been evolving over several days. Imaging tests demonstrated the presence of an intraparenchymatous nodule in the lower right lobe that was determined to be a neoplastic process. Surgical resection obtained a segmentectomy piece from the right lower lobe that was 6cm×3cm at the largest diameters. Upon resection, a nodular lesion was observed that was whitish in color with well-defined edges, measuring 9mm at its maximal diameter. Microscopically, the lesion was non-encapsulated, with well-defined edges, made up of central extracellular laminae that were concentric, eosinophilic, congo red negative, and organized around small-caliber blood vessels (Fig. 1). In the periphery of the lesion, we identified a reactive lymphocytic population made up of lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers (Fig. 1). We observed patches of multinucleated giant cells, whose presence was related with an active process of the disease. The PAS, Giemsa and Ziehl-Nielsen stained identified no microorganisms. With these data, the diagnosis was determined to be pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma. This pathology was described for the first time in 1977 by Engleman et al.,1 who postulated that PHG represented an exaggerated immune response against infectious processes such as tuberculosis and histoplasmosis, likewise demonstrating that sclerosing mediastinitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, posterior uveitis and optic papillitis were diseases associated with PHG because they all presented the same active response against infectious agents. Schlosnage et al.2 supported this theory by demonstrating the presence of different antibodies and circulating immune complexes in patients with PHG. Some authors,3,4 related the presence of reactive lymphocyte proliferation in the periphery of the lesion with lymphoproliferative processes such as multiple myeloma, lymphoma and plasma-cell type Castleman's disease. Our case did not present any of these lymphoid pathologies but did present a history of childhood tuberculosis, which would mean that its etiology may have been of the infectious type. Areas of ischemic necrosis, cavitations, bone metaplasia and calcifications are rare.5 25% of cases represent a coincidental finding in asymptomatic patients who present uni- or bilateral nodules and whose size does not usually surpass 4cm in maximum diameter. Its presentation as a single nodule, as the present case, is uncommon, a reason why many times it is misinterpreted as a solitary metastatic nodule. Both the histologic study and immunohistochemistry offer us sufficient data in order to differentiate between the two.

Within the group of intraparenchymatous primary tumors that present as nodular lesions, we can highlight solitary fibrous tumors, which are subpleural and show positivity for CD34 and BCL-2, and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors, which usually first affect the pleura and later the adjacent mediastinum. Histologically, they present cell proliferation with myofibroblastic differentiation and chronic inflammatory infiltrates, distributed in a densely sclerosing stroma similar to PHG, although in the latter the stroma is made up of concentric hyalinized structures. Within the benign pathologies that present as intraparenchymatous nodules, the most striking is nodular pulmonary amyloidosis because it presents histologic characteristics similar to our case, but clinically it does not extend to the mediastinum. Although sometimes PHG may present positivity to congo red stain just like amyloidosis, Guccion et al.4 demonstrated a fibrillar aspect of the deposit of amyloid with electron microscopy, unlike PHG, which is denser and homogeneous. There are other benign pulmonary pathologies that can be included in the extensive list of differential diagnoses, but each one is characterized by presenting specific symptoms and histologic characteristics. Among these are pulmonary rheumatoid nodule disease, Wegener's granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, histoplasmosis and last of all pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma or Langerhans cell granulomatosis.

To summarize, PHG is an uncommon lung pathology included within the large variety of benign or malignant lung lesions. The symptoms are not very specific, the evolution is slow and the possible association with other diseases requires a histopathologic study in order to correctly diagnose this disease.

Please cite this article as: Boutayeb L, et al. Granuloma pulmonar hialinizante. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48:344–5.