Immunotherapy has been accepted in recent years as an effective treatment for selected patients with locally advanced and metastatic non-small cell lung cancer,1–3 although its use can also be associated with unusual side effects that can sometimes pose a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We report the case of a patient with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma who, after treatment with nivolumab, developed tumor pseudoprogression that was initially misinterpreted, leading to her being referred for palliative care.

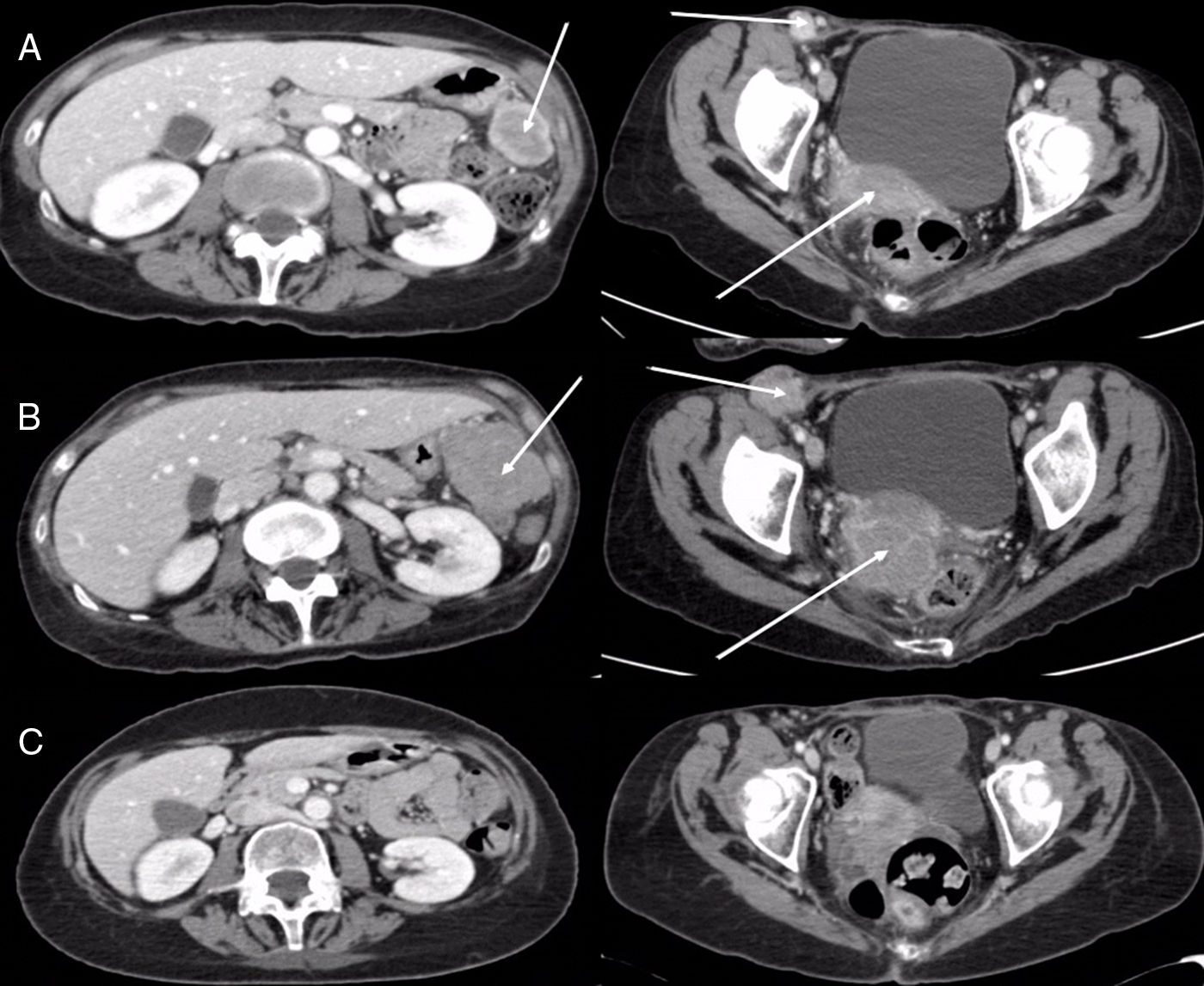

This was a 55-year-old woman who presented with headache, nausea, and vomiting. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head showed a brain lesion in the right temporal lobe measuring 2.5×2.5cm, with significant edema and midline shift. Whole body CT revealed a solitary pulmonary nodule in the right apex, measuring 23mm, consistent with primary neoplasm. PET-CT was performed, showing a lesion with intense uptake in the right upper lung (RUL), suggestive of malignancy, with no evidence of viable tumor tissue with affinity for 18F-FDG in any other site. The patient underwent surgery for the brain lesion, and the pathology study reported metastatic adenocarcinoma of possible pulmonary origin (positive CK7 and TTF1, and negative CK20, hormone receptors, melanocyte markers, and neuroendocrine markers). She subsequently received holocranial radiotherapy and then underwent surgery for her lung lesion with right upper lobectomy and mediastinal lymphadenectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS). The pathology report was consistent with lung adenocarcinoma (final definitive staging was pT2aN0M1b due to involvement of the visceral pleura). The molecular study showed no mutations or molecular translocations (EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, ALK and ROS1-negative). The patient received 2 cycles of cisplatin+pemetrexed, and her first follow-up CT performed 8 weeks later revealed the appearance of right inguinal lymphadenopathy and tumor-like pelvic masses located theoretically in the right uterine appendage and in the left paracolic gutter, so second-line treatment with nivolumab began (3mg/kg every 15 days). Imaging studies performed at 8 weeks showed progression of the abdominopelvic and brain lesions, and the patient's general condition had deteriorated (ECOG 3), so she was referred to the palliative care unit. One year later, she attended the clinic with improvement of her general condition (ECOG 1) and a CT performed for re-assessment revealed that the abdominopelvic lesions and the brain lesions seen on the head MRI had disappeared (Fig. 1). The patient is currently in complete radiological response after 41 months of follow-up.

(A) Axial CT images of abdomen (left) and pelvis (right) showing right inguinal lymphadenopathy, a mass in the right adnexal region, and another in the left paracolic gutter (arrows). (B) Axial CT images of abdomen (left) and pelvis (right) obtained 8 weeks later, showing a striking increase in tumor lesions (arrows). (C) Axial CT images of abdomen (left) and pelvis (right) obtained 12 months later, demonstrating the disappearance of tumor lesions.

In recent years, the therapeutic options for advanced non-small cell lung cancer have increased significantly. This new therapeutic arsenal benefits some patients, but has introduced some different forms of toxicity. In this respect, immunomodulatory drugs may lead to complications associated with the immune system, with other comorbidities or treatments, and even paradoxical responses.4 Pseudoprogression is a form of clinical response consisting of radiological worsening of the disease during treatment for an undetermined period of time, that subsequently resolves.5 First described during the treatment of brain lesions, this phenomenon has been observed in up to 15% of patients with melanoma who receive immunotherapy, but it is rare in lung cancer,6 with a prevalence in the latter of less than 2%,5 apparently caused by T cells infiltrating the tumor, with the resulting edema and/or necrosis. The absence of true progression can only be confirmed non-invasively with radiological studies,7 so it is sometimes very difficult to decide whether to continue or suspend treatment. This has led to the WHO or RECIST criteria for the definition of therapeutic response being replaced by new immune-mediated response criteria, such as the immune-related response criteria (irRC), the immune-related response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (irRECIST1.1), and the immune RECIST (iRECIST).8–10 The main contribution of these new response criteria (which define pseudoprogression and unconfirmed progression) is to underline that patients may be responding favorably to treatment despite a temporary increase in the tumor burden, or even after the appearance of new lesions. Definitive confirmation as to whether a possible pseudoprogression is true disease progression requires an increase in tumor volume confirmed in 2 imaging studies conducted at least 4–8 weeks apart.11

In summary, it appears that immunotherapy is changing the treatment of lung cancer,12,13 but its use has brought with it new side effects and new challenges in the assessment of radiological response, which will require new training for professionals involved in the treatment and follow-up of these patients. Despite the fact that pseudoprogression seems to be rare in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy, the possibility of performing invasive techniques should always be evaluated, since a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate in biopsy material can help differentiate pseudoprogression from progression.14 Another factor to take into account is that pseudoprogression is not generally associated with a significant clinical deterioration of the patient, a situation which would usually indicate real progression.5

Please cite this article as: Cabañero A, Gorospe L, Olmedo ME, Mezquita L. Pseudoprogresión en una paciente con adenocarcinoma pulmonar metastásico tratada con nivolumab. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019;55:168–169.