Non-cystic fibrosis-associated bronchiectasis (NCFB) is a chronic lung disease characterized by frequent exacerbations. In patients with NCFB, inhaled antibiotics provide higher infection site concentrations without systemic side effects. However, little evidence is available on nebulized antibiotic therapy in children1,2.

This study, based on the work of Máiz et al.3,4, aimed to analyze the effectiveness and safety of inhaled ampicillin therapy in children with NCFB colonized by ampicillin-sensitive Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae), penicillin-sensitive Streptococcus pneumoniae (PSSP), methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), or polymicrobial flora.

Medical records collected between 31/07/2014 and 31/03/2020 were reviewed. We included patients younger than 18 years of age diagnosed with NCFB colonized with any of the respiratory pathogens listed above who had ≥ 3 respiratory exacerbations per year and/or persistent symptoms without meeting respiratory exacerbation criteria5 (prolonged productive cough, unexplained recurrent fever, qualitative or quantitative change in expectoration). Patients were administered inhaled ampicillin after their parents or guardians gave consent for off-label use of the antibiotic.

The drug was prepared by diluting one vial of intravenous sodium ampicillin in 4 mL of water for injection. The resulting osmolarity was approximately 650 mOsm/kg. The dose used was 500 mg/12 h, and the solution was administered using either a vibrating mesh nebulizer (e-Flow®rapid) or a high-flow nebulizer (Pari Boy® SX), via an oronasal mask or a mouthpiece, depending on patient age and/or collaboration.

The minimum treatment time was 4 months. Rest periods took place in the months of lower circulation of respiratory viruses6.

Criteria for discontinuation were: resolution of respiratory symptoms; number of respiratory exacerbations ≤ 1 every 6 months; isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) or aminopenicillin-resistant pathogens; adverse effects; refusal of treatment.

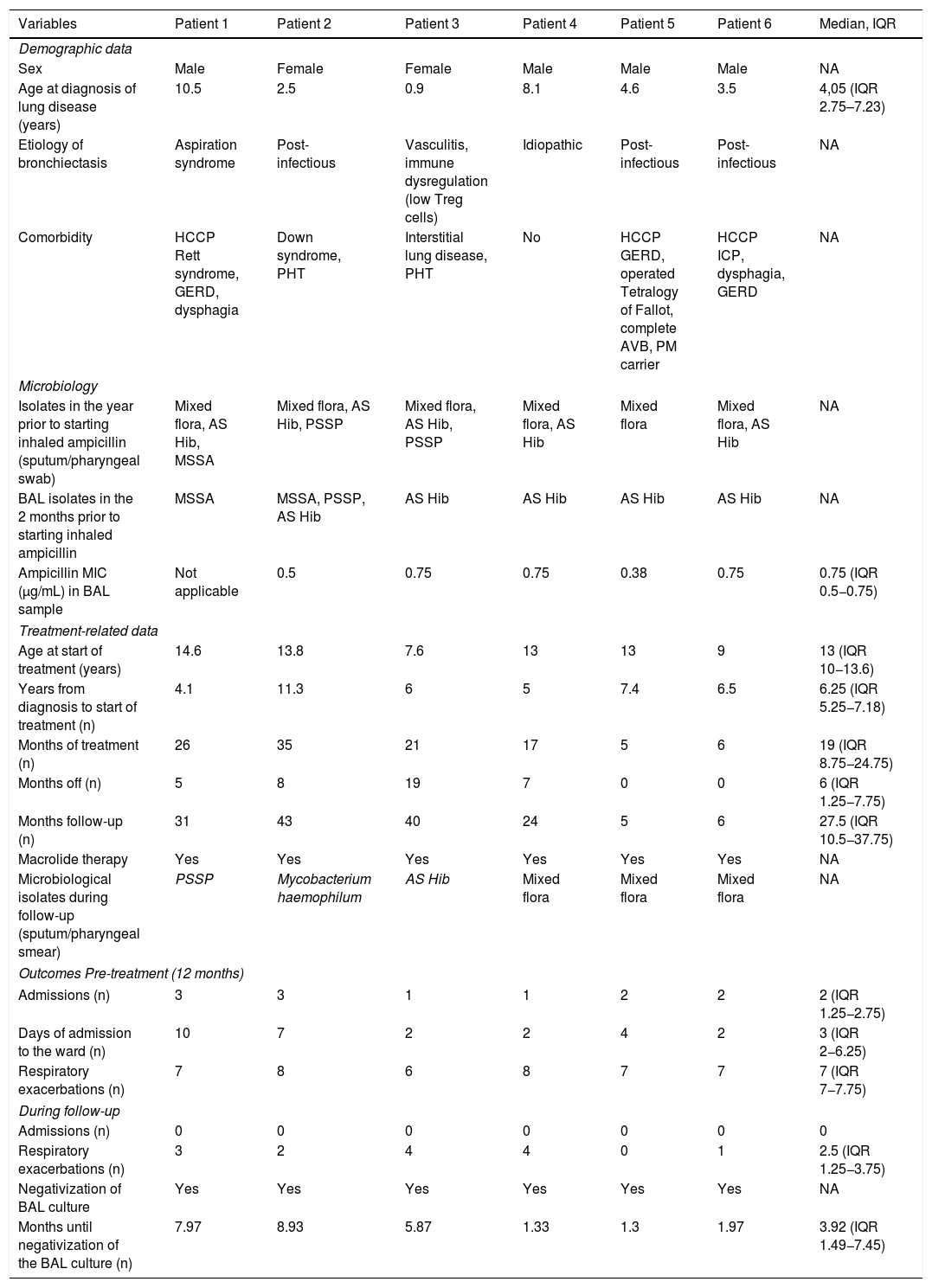

A total of 6 patients were included, 4 of whom were boys. The median age at baseline was 13 years (IQR 10−13.6). Five patients presented other comorbidities, 3 of whom (patients 1, 5 and 6) were children with highly complex chronic disease7 (Table 1).

Descriptive summary of the main variables collected and study results.

| Variables | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Median, IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||||||

| Sex | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | Male | NA |

| Age at diagnosis of lung disease (years) | 10.5 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 8.1 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 4,05 (IQR 2.75–7.23) |

| Etiology of bronchiectasis | Aspiration syndrome | Post-infectious | Vasculitis, immune dysregulation (low Treg cells) | Idiopathic | Post-infectious | Post-infectious | NA |

| Comorbidity | HCCP Rett syndrome, GERD, dysphagia | Down syndrome, PHT | Interstitial lung disease, PHT | No | HCCP GERD, operated Tetralogy of Fallot, complete AVB, PM carrier | HCCP ICP, dysphagia, GERD | NA |

| Microbiology | |||||||

| Isolates in the year prior to starting inhaled ampicillin (sputum/pharyngeal swab) | Mixed flora, AS Hib, MSSA | Mixed flora, AS Hib, PSSP | Mixed flora, AS Hib, PSSP | Mixed flora, AS Hib | Mixed flora | Mixed flora, AS Hib | NA |

| BAL isolates in the 2 months prior to starting inhaled ampicillin | MSSA | MSSA, PSSP, AS Hib | AS Hib | AS Hib | AS Hib | AS Hib | NA |

| Ampicillin MIC (μg/mL) in BAL sample | Not applicable | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.75 (IQR 0.5−0.75) |

| Treatment-related data | |||||||

| Age at start of treatment (years) | 14.6 | 13.8 | 7.6 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 13 (IQR 10−13.6) |

| Years from diagnosis to start of treatment (n) | 4.1 | 11.3 | 6 | 5 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 6.25 (IQR 5.25−7.18) |

| Months of treatment (n) | 26 | 35 | 21 | 17 | 5 | 6 | 19 (IQR 8.75−24.75) |

| Months off (n) | 5 | 8 | 19 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 6 (IQR 1.25−7.75) |

| Months follow-up (n) | 31 | 43 | 40 | 24 | 5 | 6 | 27.5 (IQR 10.5−37.75) |

| Macrolide therapy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Microbiological isolates during follow-up (sputum/pharyngeal smear) | PSSP | Mycobacterium haemophilum | AS Hib | Mixed flora | Mixed flora | Mixed flora | NA |

| Outcomes Pre-treatment (12 months) | |||||||

| Admissions (n) | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 (IQR 1.25−2.75) |

| Days of admission to the ward (n) | 10 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 (IQR 2−6.25) |

| Respiratory exacerbations (n) | 7 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 (IQR 7−7.75) |

| During follow-up | |||||||

| Admissions (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory exacerbations (n) | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 (IQR 1.25−3.75) |

| Negativization of BAL culture | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Months until negativization of the BAL culture (n) | 7.97 | 8.93 | 5.87 | 1.33 | 1.3 | 1.97 | 3.92 (IQR 1.49−7.45) |

AVB: Atrioventricular block; AS Hib: ampicillin-sensitive Haemophilus influenzae; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; BCH: Bronchiectasis; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux; HCCP: highly complex chronic patient; ICP: infantile cerebral palsy; MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration; MSSA: methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; PM: pacemaker; PSSP: penicillin-sensitive S. pneumoniae; Treg: regulatory T cells.

The median duration of treatment and follow-up were 17.5 (IQR 8.75–24) and 25.5 (IQR 10.5–30) months, respectively. Only patient 4 had discontinued ampicillin by the end of the study.

During follow-up, no aminopenicillin-resistant microorganisms or PA were isolated. In patient 2, Mycobacterium haemophilum was isolated but this finding was neither confirmed in subsequent cultures nor was it clinically relevant.

After treatment initiation, no admissions were recorded (p = 0.0003) and a significant decrease in the median number of exacerbations (p = 0.027) from 7 (IQR 7−7.75) to 2.5 (IQR 1.25−3.75) was observed. In the 2 years following drug discontinuation, patient 4 received more than 10 antibiotic cycles for respiratory exacerbations.

In all patients, cultures of secretions became negative during treatment, with a median of 3.92 (IQR 1.49−7.45) months until negativization.

No adverse effects were detected. Table 1 summarizes patient characteristics and outcomes.

Nebulized aminopenicillin therapy in patients with chronic lung diseases has been studied by other authors who reported favorable results8. Clinical trials with inhaled amoxicillin-clavulanic acid have also demonstrated the safety and good tolerance of this treatment9. However, this is the first study to explore nebulized ampicillin in children with NCFB. In 2009, Maiz et al.3,4 published a series of 13 patients with bronchiectasis caused by cystic fibrosis and chronic MSSA colonization, showing a decrease in the number of hospital admissions and the use of systemic antibiotics after prolonged treatment with inhaled ampicillin. Although the MSSA isolated in sputum cultures were penicillin-resistant, the efficacy of treatment was probably due to the high lung concentrations achieved by administering the antibiotic by inhalation, levels that were higher than the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for the targeted microorganisms10,11. In our study, all ampicillin-sensitive H. influenzae isolates in BAL were sensitive to ampicillin, although the MICs for MSSA or PSSP were not reached. However, despite this, and in line with other studies, our patients responded to nebulized ampicillin, probably for the reason stated above10–12. In contrast to Maiz’s series, none of our patients presented chronic colonization by these pathogens: apart from during exacerbations and in the year before starting ampicillin, mixed polymicrobial flora or a single microorganism were identified in the respiratory samples. Some of these exacerbations may have been initiated by respiratory viruses6. However, exacerbations could have declined because, rather than eradicating a single pathogen, prolonged treatment with nebulized ampicillin decreases the pulmonary bacterial load that is probably high in patients with bronchiectasis13–15. Furthermore, the pathogens commonly identified in children with NCFB15 are mostly sensitive to aminopenicillins (more so if higher drug concentrations are achieved by inhalation), which would also explain our patients’ improvement.

The outcomes mentioned in previous studies were favorable3,4,8,9, although it must be said that they were conducted in adults with diseases other than those presented by our patients. We must remember that the main reason for the off-label use of a drug that has only been tested in adults was the shortage of therapeutic options: our patients mostly had multiple conditions and no option for curative treatment, despite having tried other treatments administered according to the recommendations of the latest clinical practice guidelines1,2,12,16.

This study has limitations: it was a retrospective, before-and-after study without a control group, conducted in a small, heterogeneous group of cases with varying lengths of follow-up. Even so, we observed a statistically significant decrease in admissions and respiratory exacerbations.

Therefore, we conclude that long-term inhaled ampicillin therapy appears to be a safe and effective option in children with NCFB colonized by common pathogens who have frequent exacerbations. However, more extensive, randomized, homogeneous studies are needed to confirm these results and determine the optimal duration and regimen of inhaled ampicillin therapy.

Funding AcknowledgementsThe authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Torres Lobato MR, Mejías Trueba M, Rodríguez Ramallo H, Álvarez del Vayo Benito C, Iglesias Aguilar MC, Gaboli M. Tratamiento prolongado con ampicilina inhalada en pacientes pediátricos con bronquiectasias no relacionadas con la fibrosis quística. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:662–664.