Few studies have examined the 24-h symptom profile in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The main objective of this study was to determine daily variations in the symptoms of patients with stable COPD in Spain, compared with other European countries.

MethodsObservational study conducted in 8 European countries. The results from the Spanish cohort (n=122) are compared with the other European subjects (n=605). We included patients with COPD whose treatment had been unchanged in the previous 3 months. Patients completed questionnaires on morning, day-time, and night-time symptoms of COPD, the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), and the COPD and Asthma Sleep Impact Scale (CASIS).

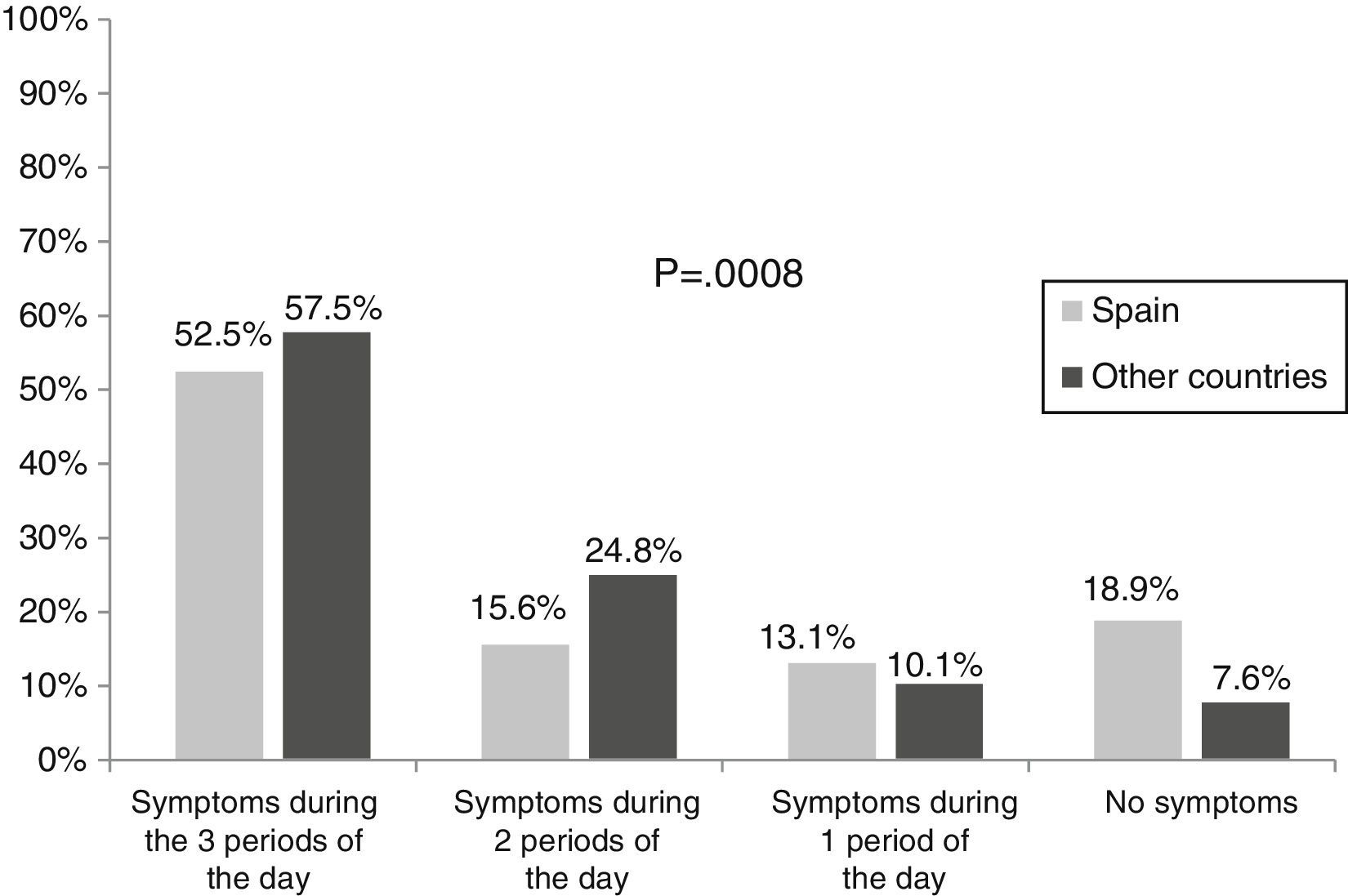

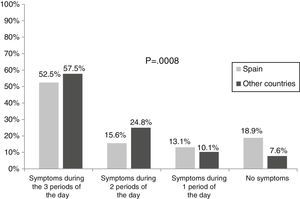

ResultsMean age: 69 (standard deviation [SD]=9) years; mean post-bronchodilator FEV1: 50.5 (SD=19.4)% (similar in Spanish and European cohorts). The proportion of men among the Spanish cohort was greater (91.0% versus 60.7%, P<.0001). A total of 52.5% patients experienced some type of symptoms throughout the day, compared to 57.5% of the other Europeans (P<.001). Patients with symptoms throughout the day had poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and higher levels of anxiety/depression than patients without symptoms. Patients with night-time symptoms had a poorer quality of sleep. Spanish patients with symptoms throughout the day had better CAT scores (16.9 versus 20.5 in the other Europeans, P<.05).

ConclusionsDespite receiving treatment, more than half of patients report symptoms throughout the day. These patients have poorer HRQoL and higher levels of anxiety/depression. Among patients with similar lung function, the Spanish cohort was less symptomatic and reported better HRQoL than other Europeans.

Hay pocos estudios sobre la distribución circadiana de los síntomas de la enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) durante las 24h del día. El objetivo principal fue conocer la variabilidad diaria de los síntomas en pacientes con EPOC estable en España en comparación con otros países europeos.

MétodosEstudio observacional realizado en 8 países europeos. Se presentan resultados de pacientes españoles (n=122) versus resto de europeos (n=605). Se incluyeron pacientes con EPOC, sin modificaciones en el tratamiento en los 3meses anteriores. Los pacientes rellenaron: cuestionario de síntomas matutinos, diurnos y nocturnos de la EPOC, cuestionario COPD Assessment Test (CAT), escala de ansiedad y depresión hospitalaria (HADS) y escala del impacto del sueño por asma y EPOC (CASIS).

ResultadosEdad media: 69 (DE=9) años; FEV1 posbroncodilatador medio: 50,5 (DE=19,4) % (similar en españoles y europeos). La proporción de hombres entre los españoles fue superior (91,0% versus 60,7%, p<0,0001). El 52,5% experimentaron algún tipo de síntomas durante todo el día (57,5% resto europeos, p<0,001). Los pacientes con síntomas durante todo el día tuvieron peor calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) y niveles mayores de ansiedad/depresión que los pacientes sin síntomas. Los pacientes con síntomas nocturnos tenían peor calidad del sueño. Los pacientes españoles con síntomas durante todo el día mostraron una mejor puntuación en el CAT (16,9 versus 20,5 resto europeos, p<0,05).

ConclusionesA pesar de recibir tratamiento, más de la mitad de los pacientes refieren síntomas durante todo el día. Estos pacientes presentan peor CVRS, peor calidad del sueño y niveles aumentados de ansiedad/depresión. A igual función pulmonar, los españoles son menos sintomáticos y refieren mejor CVRS en comparación con otros europeos.

The main symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are cough, expectoration, and dyspnea. Until recently, the general opinion was that COPD symptoms, unlike asthma symptoms,1 did not change much over the course of the day. However, in recent years, it has become clear that COPD patients find that their respiratory symptoms vary over the course of the day.2–4 Curiously, Kessler et al.2 observed differences among different European regions in the perception of symptom variability, but this study only included patients with severe or very severe COPD (FEV1<50% predicted).

Our group was involved in a recently published European observational study,5 designed to determine the prevalence and severity of symptoms over a 24-h period in stable COPD patients with any level of airflow limitation seen in routine clinical practice (the ASSESS study). Since a large proportion of patients in this study were recruited from Spanish hospitals, we thought that it would be interesting to perform a subanalysis of this population, in order to define the prevalence and profile of 24-h respiratory symptom patterns in patients with any stage of COPD severity, compared to patients in other European countries.5 Our secondary objective was to evaluate the relationship between COPD symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), anxiety and depression levels, quality of sleep, and COPD exacerbations.

MethodsThis was an epidemiological, observational, multicenter study performed in Spain and other European countries (Germany, Denmark, France, Netherlands, Italy, Sweden and United Kingdom) between April 2011 and November 2013. We present the results from patients included in Spain. Respiratory medicine specialists in 14 hospitals located throughout Spain (Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Catalonia, Community of Valencia, Galicia, Balearic Islands, Madrid, Navarre, and the Basque Country) took part in this study.

Patients were ≥40 years of age with an accumulated history of smoking of ≥10 pack-years and a diagnosis of COPD of any severity (stages I to IV) according to GOLD criteria (2010).6 To be included, they had to be stable, with no exacerbations in the previous month. Exclusion criteria were: modifications in COPD treatment regimen in the 3 months before the study visit, previous diagnosis of asthma, sleep apnea syndrome or chronic respiratory disease other than COPD, or any acute or chronic disease which, in the opinion of the investigator, would limit the patient's ability to participate in the study.

The study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization. All patients gave their written informed consent before inclusion. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona.

Data CollectionThe following data were collected during the study visit: demographic, anthropometric and socioeconomic characteristics, smoking habit, data from the latest available spirometry (up to 12 months previously), disease severity according to the GOLD 2010 criteria, current treatment for COPD, exacerbations in the year before the visit. Patients were also asked to complete the following questionnaires:

- a)

Night-time, morning and daytime COPD symptoms: a self-administered 33-item questionnaire, developed by the sponsor, on the frequency and severity of COPD symptoms (dyspnea, cough, expectoration, chest tightness, chest congestion, wheezing) during each time interval in the week before the visit, and in a normal week in the previous month (defined as the week considered by the patient as the most typical of the previous month). The questionnaires consist of 3 sections. The first (13 questions) addresses night-time symptoms (the time between the patient going to bed and getting up), the second (10 questions) asks about morning symptoms (between getting up and about 11 o’clock in the morning), and the third (10 questions) addresses daytime symptoms (from 11 o’clock in the morning until bedtime).

- b)

COPD Assessment Test (CAT) questionnaire7: an 8-item questionnaire evaluating HRQoL in COPD with scores from 0 to 40, higher scores representing poorer HRQoL.

- c)

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)8: a self-administered 14-item scale measuring levels of anxiety and depression (with 7 questions in each respective subscale). Scores in each subscale range from 0 to 21, higher scores representing higher levels of anxiety and depression.

- d)

COPD and Asthma Sleep Impact Scale (CASIS)9,10: a self-administered 7-item scale evaluating sleeping problems associated with COPD and asthma. Total score is from 0 to 100, higher scores representing greater sleep deterioration in the previous week.

All variables were included in a descriptive analysis: mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables and frequencies for qualitative variables. The population for analysis included patients who met all the screening criteria and completed the night-time, morning and daytime questionnaires (evaluable population). No substitution methods were used for missing data. The Chi-squared test was used to compare qualitative variables and the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test was used for continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at P<.05. All analyses were performed using the SAS® System for Windows version 9.2 statistical package.

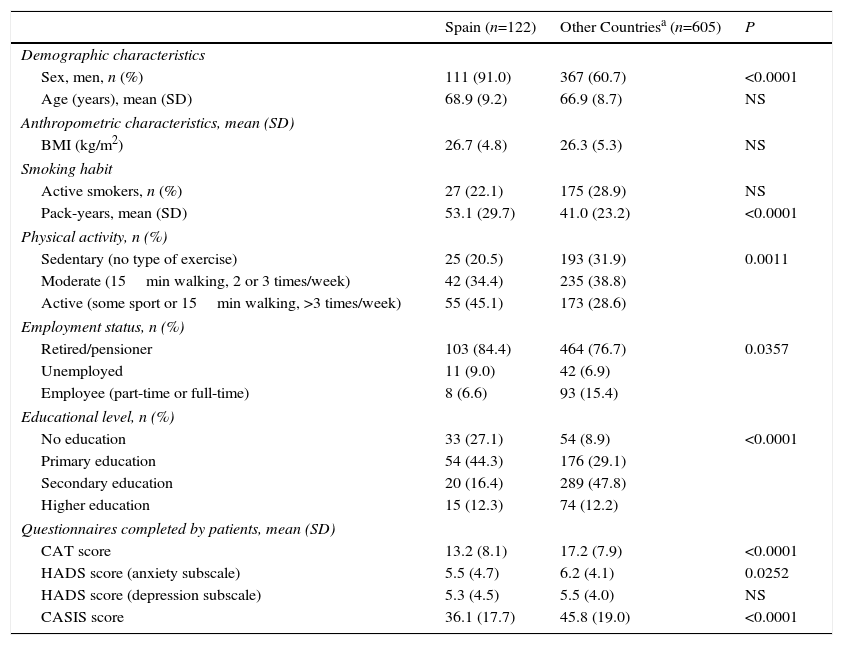

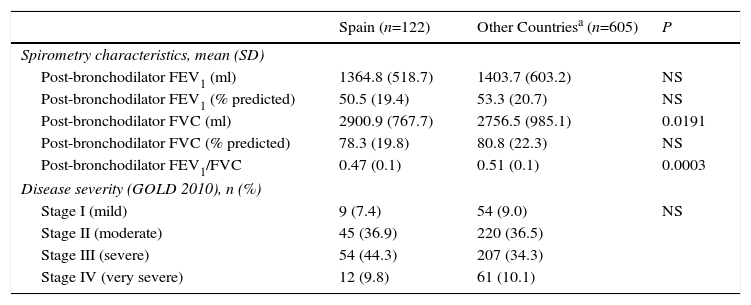

ResultsA total of 124 Spanish patients were screened: 2 (1.6%) did not fulfill the inclusion/exclusion criteria, so the final number of evaluable patients was 122. The total number of evaluable patients in other European countries was 605. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of both populations. The mean age of the Spanish cohort was 69 (SD=9) years (similar to the European mean), and most were men. In fact, the percentage of men in Spain was significantly higher than in other European countries (91.0% versus 60.7%, P<.0001). The percentage of active smokers among the Spanish group was 22.1%, similar to that of the other Europeans, but the pack-year consumption of the Spaniards was higher (P<.0001). The Spanish patients performed more physical activity (45.1% vs 28.6%, P<.01), and a greater number of them were retired (84.4% vs 76.7%, P<.05). Scores for the CAT, HADS anxiety subscale score, and the CASIS questionnaires were lower among the Spaniards (P<.05 for all) (Table 1). Mean post-bronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted) in the Spanish population was 50.5% (SD=19.4%), similar to the European group. A total of 44.3% had severe COPD (stage III) according to GOLD 2010 criteria. This proportion was numerically higher than the European population (34.3%), but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

General Characteristics of the Spanish Population (n=122) and Other European Countries (n=605).

| Spain (n=122) | Other Countriesa (n=605) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Sex, men, n (%) | 111 (91.0) | 367 (60.7) | <0.0001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 68.9 (9.2) | 66.9 (8.7) | NS |

| Anthropometric characteristics, mean (SD) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 (4.8) | 26.3 (5.3) | NS |

| Smoking habit | |||

| Active smokers, n (%) | 27 (22.1) | 175 (28.9) | NS |

| Pack-years, mean (SD) | 53.1 (29.7) | 41.0 (23.2) | <0.0001 |

| Physical activity, n (%) | |||

| Sedentary (no type of exercise) | 25 (20.5) | 193 (31.9) | 0.0011 |

| Moderate (15min walking, 2 or 3 times/week) | 42 (34.4) | 235 (38.8) | |

| Active (some sport or 15min walking, >3 times/week) | 55 (45.1) | 173 (28.6) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Retired/pensioner | 103 (84.4) | 464 (76.7) | 0.0357 |

| Unemployed | 11 (9.0) | 42 (6.9) | |

| Employee (part-time or full-time) | 8 (6.6) | 93 (15.4) | |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||

| No education | 33 (27.1) | 54 (8.9) | <0.0001 |

| Primary education | 54 (44.3) | 176 (29.1) | |

| Secondary education | 20 (16.4) | 289 (47.8) | |

| Higher education | 15 (12.3) | 74 (12.2) | |

| Questionnaires completed by patients, mean (SD) | |||

| CAT score | 13.2 (8.1) | 17.2 (7.9) | <0.0001 |

| HADS score (anxiety subscale) | 5.5 (4.7) | 6.2 (4.1) | 0.0252 |

| HADS score (depression subscale) | 5.3 (4.5) | 5.5 (4.0) | NS |

| CASIS score | 36.1 (17.7) | 45.8 (19.0) | <0.0001 |

BMI, body-mass index; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; CASIS, COPD and Asthma Sleep Impact Scale; SD, standard deviation; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NS, not significant.

Missing data (n): sex (other countries: 1), age (other countries: 2), BMI (other countries: 7), pack-years (Spain: 1; other countries: 3), physical activity (other countries: 4), employment status (other countries: 6), educational level (other countries: 12).

Lung Function Among the Spanish Population (n=122) and Other European Countries (n=605).

| Spain (n=122) | Other Countriesa (n=605) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spirometry characteristics, mean (SD) | |||

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1 (ml) | 1364.8 (518.7) | 1403.7 (603.2) | NS |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted) | 50.5 (19.4) | 53.3 (20.7) | NS |

| Post-bronchodilator FVC (ml) | 2900.9 (767.7) | 2756.5 (985.1) | 0.0191 |

| Post-bronchodilator FVC (% predicted) | 78.3 (19.8) | 80.8 (22.3) | NS |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC | 0.47 (0.1) | 0.51 (0.1) | 0.0003 |

| Disease severity (GOLD 2010), n (%) | |||

| Stage I (mild) | 9 (7.4) | 54 (9.0) | NS |

| Stage II (moderate) | 45 (36.9) | 220 (36.5) | |

| Stage III (severe) | 54 (44.3) | 207 (34.3) | |

| Stage IV (very severe) | 12 (9.8) | 61 (10.1) | |

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

Missing data (n): Post-bronchodilator FEV1 (other countries: 29), post-bronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted) (other countries: 7), post-bronchodilator FVC (other countries: 31), post-bronchodilator FVC (% predicted) (other countries: 14), post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC (other countries: 31), disease severity (Spain: 2; other countries: 61).

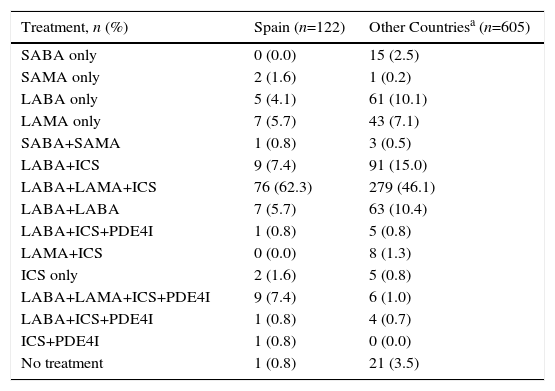

In total, 99.2% of the Spanish patients were receiving treatment for COPD. The most common treatment was a combination of a long-acting beta-2 agonist (LABA), a long-acting anticholinergic (LAMA), and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), and this combination was prescribed more frequently in Spain than in other European countries: 62.3% versus 46.1% (P<.0001). Quadruple therapy (LABA, LAMA, ICS, and a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) was prescribed to 7.4% of Spanish patients compared to 1.0% of the non-Spanish population (Table 3).

Current COPD Maintenance Treatment in the Spanish Population (n=122) and Other European Countries (n=605) (P<.0001).

| Treatment, n (%) | Spain (n=122) | Other Countriesa (n=605) |

|---|---|---|

| SABA only | 0 (0.0) | 15 (2.5) |

| SAMA only | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.2) |

| LABA only | 5 (4.1) | 61 (10.1) |

| LAMA only | 7 (5.7) | 43 (7.1) |

| SABA+SAMA | 1 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) |

| LABA+ICS | 9 (7.4) | 91 (15.0) |

| LABA+LAMA+ICS | 76 (62.3) | 279 (46.1) |

| LABA+LABA | 7 (5.7) | 63 (10.4) |

| LABA+ICS+PDE4I | 1 (0.8) | 5 (0.8) |

| LAMA+ICS | 0 (0.0) | 8 (1.3) |

| ICS only | 2 (1.6) | 5 (0.8) |

| LABA+LAMA+ICS+PDE4I | 9 (7.4) | 6 (1.0) |

| LABA+ICS+PDE4I | 1 (0.8) | 4 (0.7) |

| ICS+PDE4I | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| No treatment | 1 (0.8) | 21 (3.5) |

ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta-2 agonist; LAMA, long-acting anticholinergic; PDE4I, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor; SABA, short-acting beta-2 agonist; SAMA, short-acting anticholinergic.

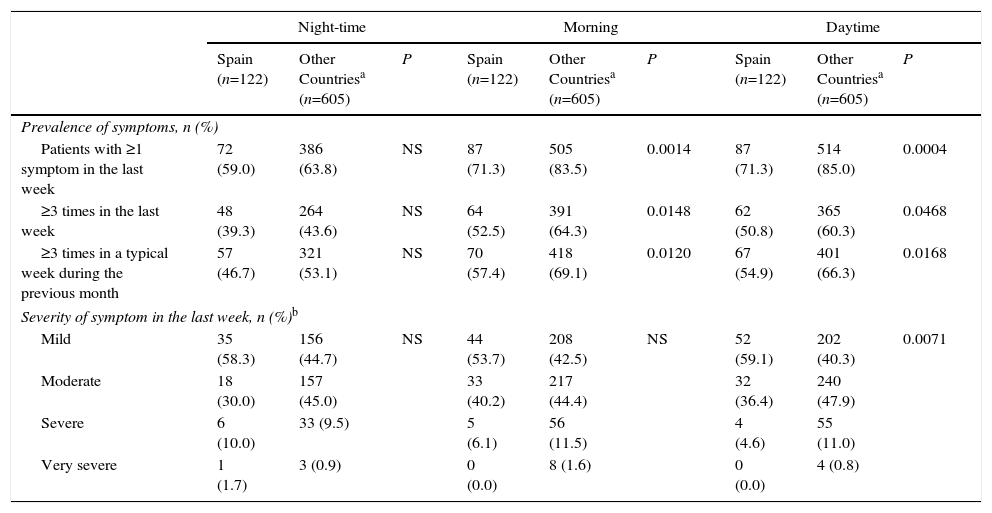

During the week before inclusion in the study, more than half of the Spanish patients (52.5%) experienced COPD symptoms during the 3 periods of the day, and 15.6% did so during 2 periods. These percentages were significantly lower (P<.001) than for patients in the rest of Europe: 57.5% and 24.8%, respectively (Fig. 1). Symptoms most frequently occurred in both the Spanish and non-Spanish populations in the morning and during the day, but to a greater extent in the non-Spaniards (71.3% vs 83.5% and 71.3% vs 85.0% morning and daytime symptoms, respectively [P<.01 for both]). Up to 59.0% of Spanish patients had at least 1 COPD symptom during the night (Table 4). Symptom severity was comparable in the different periods of the day. Most symptoms were described as mild or moderate by the Spanish cohort (93.9%, 95.5% and 83.3% reported mild or moderate symptoms during the morning, during the rest of the day or during the night, respectively). A significantly greater percentage of non-Spanish patients reported severe or very severe daytime symptoms (11.8% vs 4.6%; P<.01) (Table 4).

Prevalence and Severity of COPD Symptoms Throughout a 24-h Period in the Spanish Population (n=122) and Other European Countries (n=605).

| Night-time | Morning | Daytime | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain (n=122) | Other Countriesa (n=605) | P | Spain (n=122) | Other Countriesa (n=605) | P | Spain (n=122) | Other Countriesa (n=605) | P | |

| Prevalence of symptoms, n (%) | |||||||||

| Patients with ≥1 symptom in the last week | 72 (59.0) | 386 (63.8) | NS | 87 (71.3) | 505 (83.5) | 0.0014 | 87 (71.3) | 514 (85.0) | 0.0004 |

| ≥3 times in the last week | 48 (39.3) | 264 (43.6) | NS | 64 (52.5) | 391 (64.3) | 0.0148 | 62 (50.8) | 365 (60.3) | 0.0468 |

| ≥3 times in a typical week during the previous month | 57 (46.7) | 321 (53.1) | NS | 70 (57.4) | 418 (69.1) | 0.0120 | 67 (54.9) | 401 (66.3) | 0.0168 |

| Severity of symptom in the last week, n (%)b | |||||||||

| Mild | 35 (58.3) | 156 (44.7) | NS | 44 (53.7) | 208 (42.5) | NS | 52 (59.1) | 202 (40.3) | 0.0071 |

| Moderate | 18 (30.0) | 157 (45.0) | 33 (40.2) | 217 (44.4) | 32 (36.4) | 240 (47.9) | |||

| Severe | 6 (10.0) | 33 (9.5) | 5 (6.1) | 56 (11.5) | 4 (4.6) | 55 (11.0) | |||

| Very severe | 1 (1.7) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.8) | |||

NS, not significant.

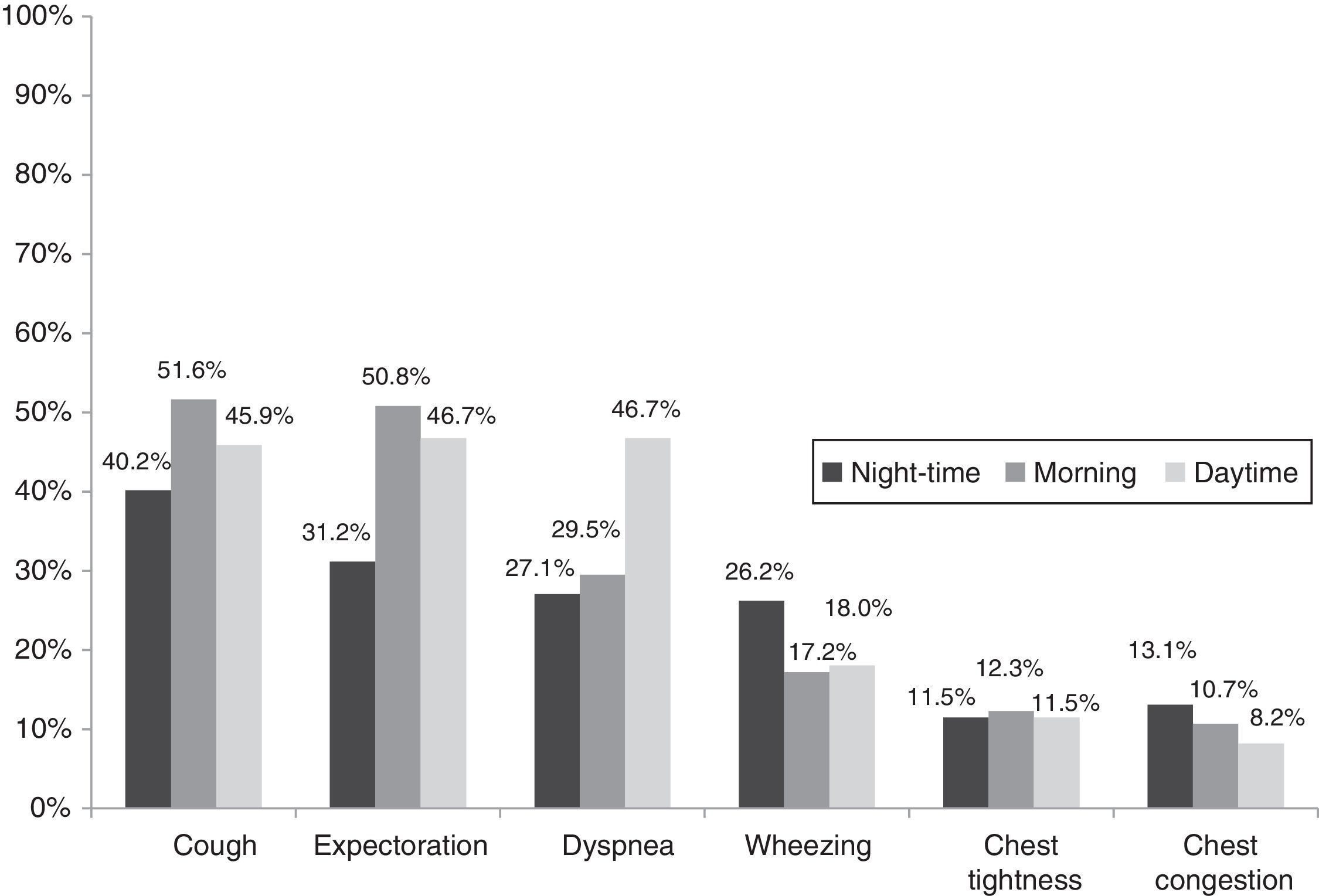

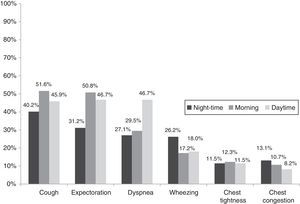

Cough (reported by 59.8% of the Spanish group), expectoration (57.4%) and dyspnea (53.3% Spanish vs 75.0% non-Spanish; P<.0001) were the most common COPD symptoms among the Spanish population, followed by wheezing, chest tightness or congestion (each reported by 15.6% of the population). The frequency of each individual symptom varied over the 24h of the day. Cough and expectoration were more common in the morning and dyspnea-related symptoms increased during the day. Wheezing was more common at night than during the day (Fig. 2). Morning or daytime dyspnea, reported by 29.5% and 46.7% of the Spanish population, increased to 56% and 68.9%, respectively, in the non-Spanish population (P<.0001 for both).

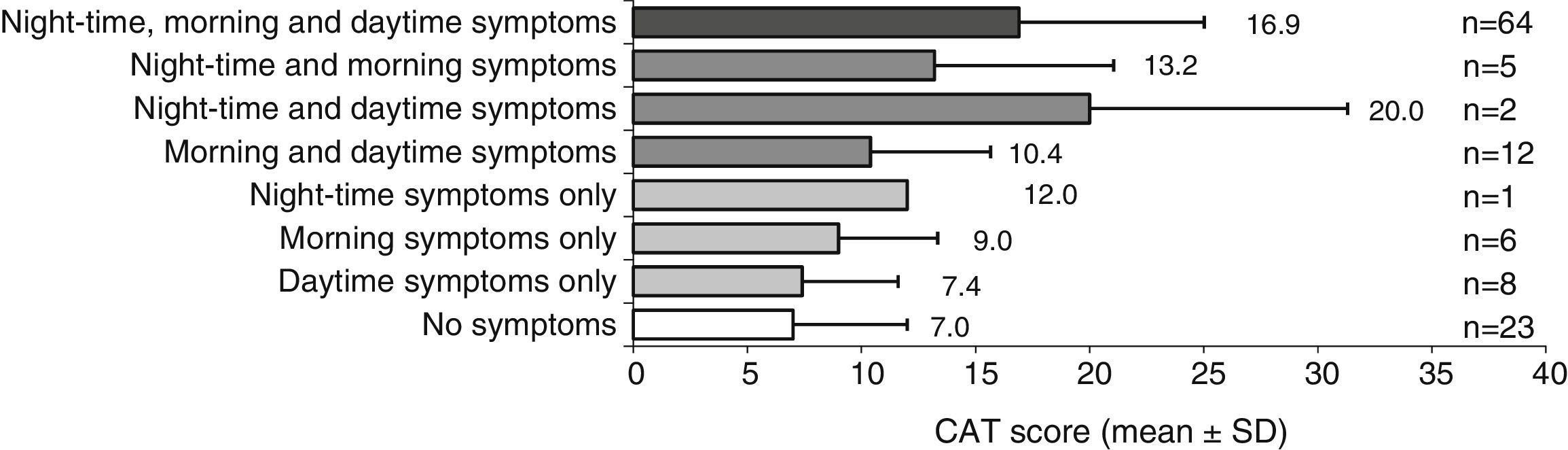

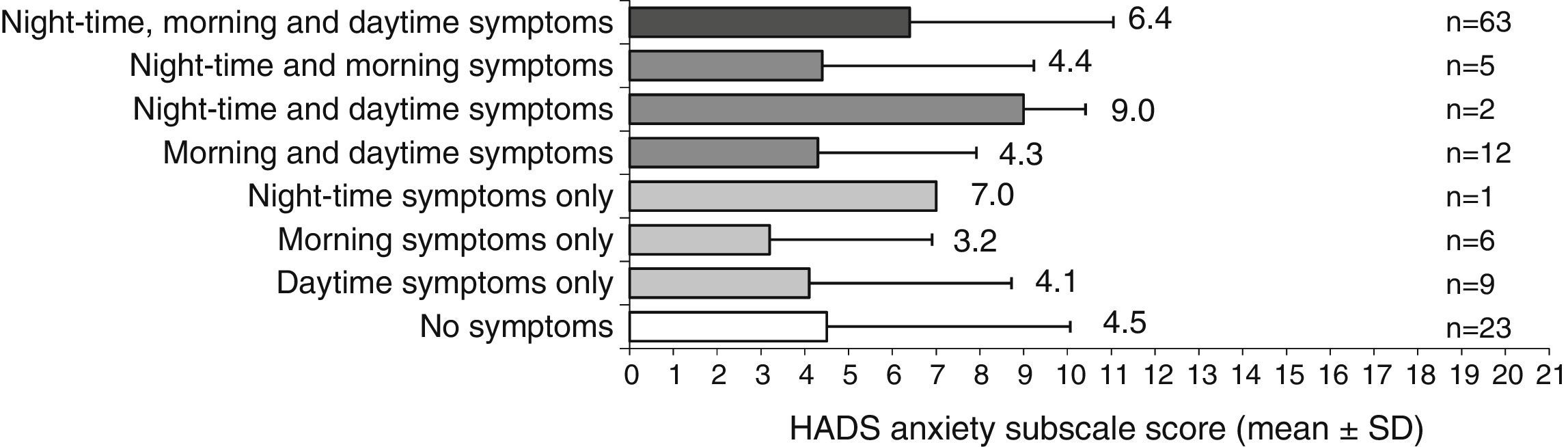

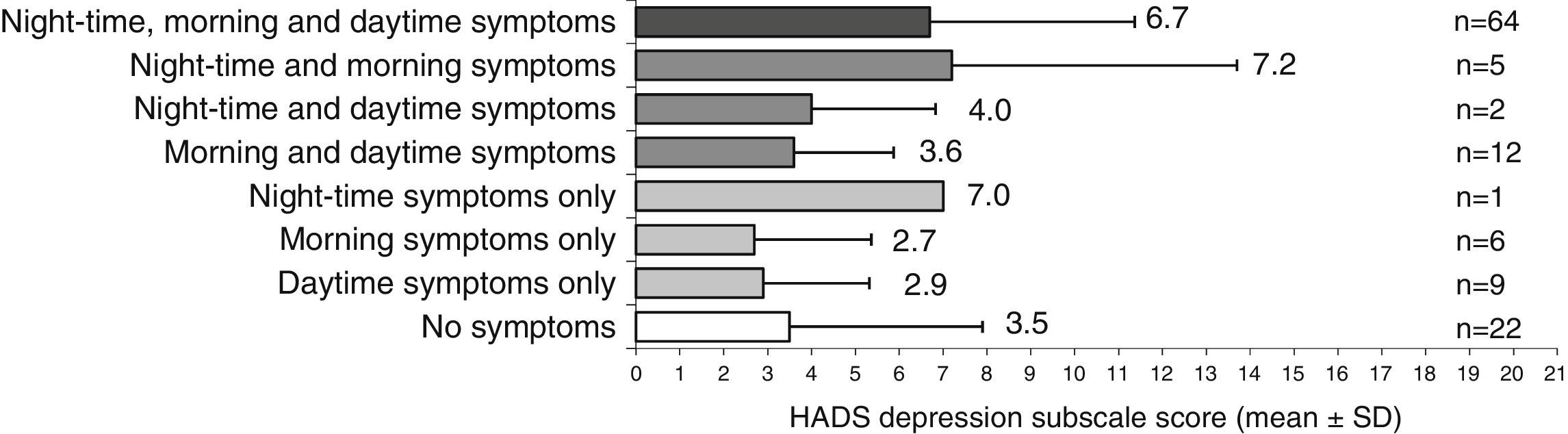

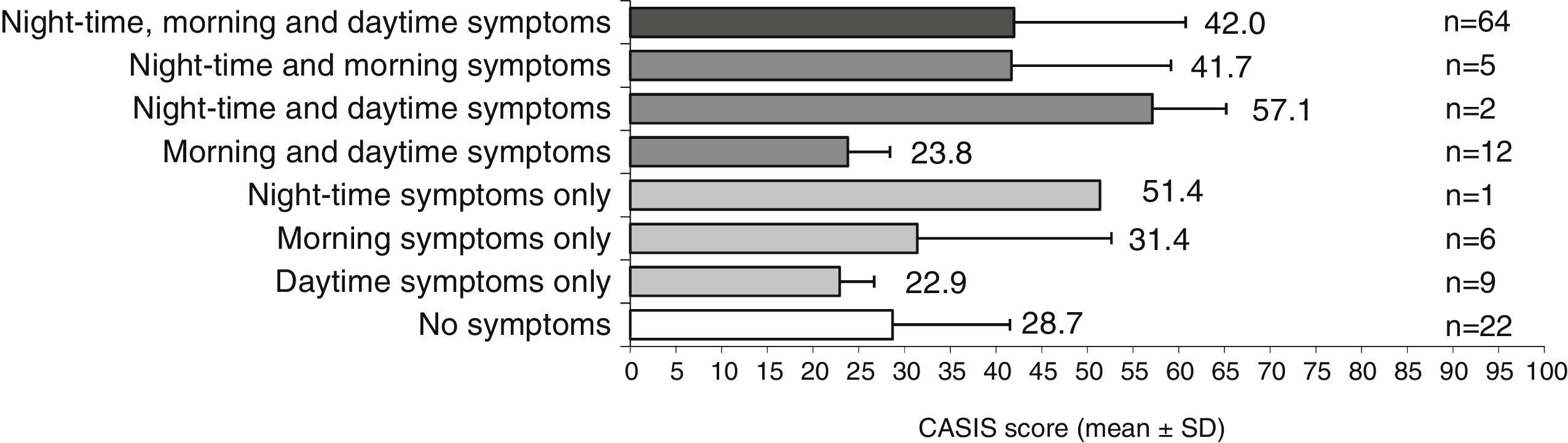

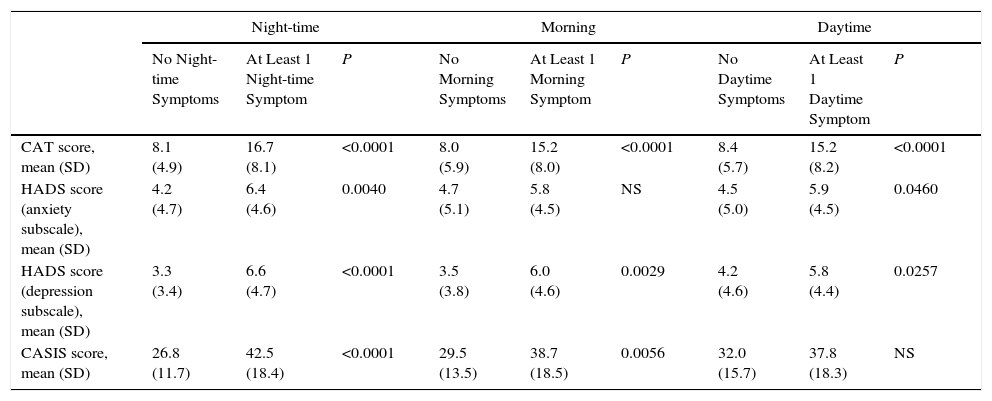

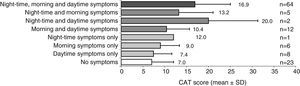

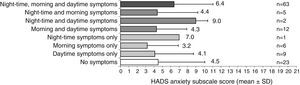

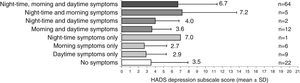

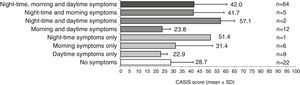

Patients with symptoms throughout the day had poorer HRQoL and higher levels of anxiety and depression than symptom-free patients (Figs. 3–5). CAT questionnaire scores were lower for Spanish patients with daytime symptoms than for the non-Spanish population (16.9 vs 20.5, P<.05). Patients with night-time COPD symptoms had a poorer quality of sleep than those without night-time symptoms (Fig. 6). CASIS scale scores were lower for Spanish patients with symptoms during the 3 periods of the day than for the non-Spanish population (42.0 vs 52.8, P<.05).

When the scores were analyzed by time periods, the CAT score was significantly worse in patients with at least 1 COPD symptom during the morning, the day or at night, compared to patients who were symptom-free in the same time intervals (P<.0001 for all) (data for the Spanish population shown in Table 5). Moreover, anxiety levels were significantly higher in patients with at least 1 symptom during the night or the day, compared to patients who were symptom-free in the same period (P<.05 for both). Depression levels were also higher in patients with at least 1 symptom at night, in the morning or during the day, compared to symptom-free patients in the same time intervals (P<.05 for all). Patients with at least 1 COPD symptom during the night or in the morning had a significantly poorer quality of sleep than patients who were symptom-free during the same time intervals (P<.01 for both).

CAT, HADS and CASIS Questionnaire Scores, According to Presence of Respiratory Symptoms in the Spanish Population (n=122).

| Night-time | Morning | Daytime | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Night-time Symptoms | At Least 1 Night-time Symptom | P | No Morning Symptoms | At Least 1 Morning Symptom | P | No Daytime Symptoms | At Least 1 Daytime Symptom | P | |

| CAT score, mean (SD) | 8.1 (4.9) | 16.7 (8.1) | <0.0001 | 8.0 (5.9) | 15.2 (8.0) | <0.0001 | 8.4 (5.7) | 15.2 (8.2) | <0.0001 |

| HADS score (anxiety subscale), mean (SD) | 4.2 (4.7) | 6.4 (4.6) | 0.0040 | 4.7 (5.1) | 5.8 (4.5) | NS | 4.5 (5.0) | 5.9 (4.5) | 0.0460 |

| HADS score (depression subscale), mean (SD) | 3.3 (3.4) | 6.6 (4.7) | <0.0001 | 3.5 (3.8) | 6.0 (4.6) | 0.0029 | 4.2 (4.6) | 5.8 (4.4) | 0.0257 |

| CASIS score, mean (SD) | 26.8 (11.7) | 42.5 (18.4) | <0.0001 | 29.5 (13.5) | 38.7 (18.5) | 0.0056 | 32.0 (15.7) | 37.8 (18.3) | NS |

CASIS, Sleep and Asthma Sleep Impact Scale; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

Missing data (n): CAT score, no night-time symptoms (1), no morning symptoms (1), at least 1 daytime symptom (1); HADS anxiety subscale, at least 1 night-time symptom (1), at least 1 daytime symptom (1); HADS depression subscale score, no night-time symptoms (1), no morning symptoms (1), CASIS score, no night-time symptoms (1), no morning symptoms (1), no daytime symptoms (1).

With respect to COPD exacerbations in Spanish patients, night-time or daytime symptoms were significantly associated with the number of exacerbations in the previous year, although the association with morning symptoms was not significant. The mean number of exacerbations was greater in patients with at least 1 COPD symptom during the night or the day, compared to patients who were symptom-free during the same time intervals (1.6 [SD=1.7] exacerbations vs 0.9 [SD=1.1], and 1.5 [SD=1.6] exacerbations vs 0.8 [SD=1.2], respectively; P<.05 for all).

DiscussionOur study revealed that more than half (53%) of Spanish patients with COPD receiving stable treatment and in any stage of disease severity experience symptoms during all periods of the day (morning, day and night), two thirds (68%) during at least 2 periods of the day, and 81% during at least 1 time interval. Morning symptoms, particularly cough and expectoration, are the most common. However, up to 59% of patients are also symptomatic at night.

It is interesting to note that the European population was generally more symptomatic than the Spanish.5 A total of 58% reported symptoms throughout the day and 82% in 2 or 3 periods during the day: these percentages were significantly higher than in the Spanish population. Moreover, Spanish patients reported fewer daytime symptoms, compared to the European population.5 Among the European population, 84% reported at least 1 morning symptom and 85% had at least 1 daytime symptom, compared to 71% of the Spanish group who had at least 1 morning or daytime symptom.

These differences between the 2 populations were maintained, despite similarities in airflow limitation. Moreover, the perception of symptom severity during the day differed slightly, with almost all Spanish patients (96%) reporting symptoms as mild or moderate, compared to 88% of the European population. The correlation between lung function compromise and the perception of symptoms is weak,11 so other factors may be contributing to the low rate of symptoms reported by the Spanish group. It is interesting to note that mean scores obtained in both the CAT and the CASIS scale for the Spanish population with night-time, morning or daytime symptoms were lower than the scores obtained for the European population,5 confirming a better HRQoL and a better quality of sleep in the Spanish population compared to the general, more symptomatic, European population.

There could be many reasons to explain why Spanish patients are less symptomatic or have a better HRQoL, but a key factor may be their COPD maintenance treatment. Most Spanish patients (up to 70%) received a combination of LABA, LAMA, and ICS, and this regimen was prescribed to a significantly higher percentage of Spaniards than Europeans (47%).

Nine out of 10 Spanish patients were men, compared to 6 out of 10 in other European countries.5 This greater proportion of men in the Spanish cohort may also contribute to the fact that HRQoL was better and Spanish patients were less symptomatic than the European population. Some authors have shown that women with COPD have worse HRQoL and report more respiratory symptoms than men, even when their disease is similarly severe.12–14 Nevertheless, the greater proportion of men among the Spanish COPD group may be explained by the lower prevalence of COPD among women in Spain,15 and by the higher rates of underdiagnosis in women compared to men.16 We should also remember that the Spanish patients were more physically active than their Europeans counterparts (perhaps because there were more retired subjects in the Spanish group), a factor associated with better HRQoL in COPD patients.17

Cough and expectoration were the symptoms most commonly reported by the Spanish, while in the European population, it was dyspnea.15–18 Dyspnea is one of the factors most closely associated with HRQoL.19 Cough and expectoration are typical symptoms of the chronic bronchitis COPD phenotype,20 and are associated with more frequent exacerbations and hospitalization.21 In our study, Spanish patients who reported at least 1 night-time or daytime COPD symptom had approximately twice the number of exacerbations in the previous year, compared to those who reported no symptoms in the same time periods. Roche et al.22 reported that patients with morning COPD symptoms typically had a higher rate of exacerbations compared to those without morning symptoms, although in this earlier study, patients with morning symptoms were significantly older, and were more often active smokers with poorer lung function than patients without morning symptoms. We did not have the necessary data to compare demographic or clinical characteristics according to symptoms, but we are not surprised to see a relationship between patient-reported symptoms and the number of exacerbations, since exacerbations involve worsening respiratory symptoms. Moreover, in more symptomatic patients, it is more likely that worsening symptoms will exceed the threshold of normal diurnal variation and develop into an exacerbation.

When the distribution of symptoms throughout the 24-h period was analyzed, we found that our population more frequently reported morning symptoms. Other observational studies also found that patients report more intense symptoms in the morning, when they get up,2,4,23 and these symptoms impact greatly on their health status and activities of daily living.2,22–26 In our study, HRQoL was significantly compromised in patients with at least 1 morning COPD symptom, compared to patients with no symptoms in the same time interval; the same patients also had higher scores in the HADS depression subscale.

Up to 60% of both the Spanish and the European population had night-time symptoms.5 Night-time symptoms were significantly associated with poorer HRQoL and higher scores on both the anxiety and depression subscales of the HADS. Furthermore, patients with night-time symptoms had a poorer quality of sleep, so our results support a correlation between quality of sleep and HRQoL in COPD patients.27 Price et al.28 also found that patients with night-time symptoms had a significantly worse health status than patients without. As might be expected, patients with a 24-h pattern of COPD symptoms are those who have poorer HRQoL and higher levels of anxiety and depression.

The observational design of this study has some inherent limitations, including a possible selection bias. The main limitation is the lack of a control group that would allow us to determine if the differences observed between the Spanish and European patients are due to inherent characteristics of their COPD or to pre-existing differences between the populations. The study design also prevents us from clarifying another important question: why does the Spanish population, with the same grade of disease severity, have a better HRQoL and fewer symptoms than the European population? Other variables not described here may possibly explain why the Spaniards reported fewer symptoms. Another point to bear in mind is that the study population is relatively small, so some care is needed when extrapolating the conclusions to all COPD patients. Larger studies would help confirm our results.

In conclusion, more than half of Spanish COPD patients show respiratory symptoms 24h a day. Morning symptoms, particularly cough and expectoration, occur more frequently. Even when symptoms are reported as mainly mild or moderate, they affect health-related quality of life. Spanish patients are less symptomatic than patients in other European countries. Healthcare professionals must pay more attention to 24-h respiratory symptom patterns in COPD, even in stable patients.

FundingThis study was funded by AstraZeneca Farmacéutica.

Author ContributionsMM designed the study, coordinated the research group and directed data analysis. JJSC, JS, LV, PM, RA and MM participated in clinical data collection, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version. JJSC was the leading investigator in Spain. MP participated in manuscript review.

Conflict of InterestsJJSC has received fees for scientific consultancy and/or for speaking at conferences organized by Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, Laboratorios Esteve, Pfizer, Menarini, Mundipharma and Novartis. MP works in the Medical Department of AstraZeneca Farmacéutica, Spain. MM has received fees for scientific consultancy and/or for speaking at conferences organized by Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Grupo Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Laboratorios Esteve, Pfizer, Teva, Cipla, Menarini, Novartis, Gebro Pharma and Takeda. The other authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Eva Mateu of the Medical Department of TFS assisted in the scientific writing of this article.

Please cite this article as: Soler-Cataluña JJ, Sauleda J, Valdés L, Marín P, Agüero R, Pérez M, et al. Prevalencia y percepción de la variabilidad diaria de los síntomas en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica estable en España. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:308–315.