Postherpetic neuralgia is the most common late complication of herpes zoster, and occurs in 9%–19% of patients.1 It is caused by nerve damage in the area affected by the virus and is defined as persistent pain longer than 3 months after resolution of the characteristic vesicular rash.2–4 The main clinical problem is persistent pain that interferes with the patient's daily activities. The chest region (dermatomes T1 to T12) is the area most commonly affected by postherpetic neuralgia, with an incidence of up to 50%.5 Various treatments have been proposed,6–10 including drugs, botulinum toxin injections, nerve blocks, peripheral nerve stimulation, surgical intervention, pulsed radiofrequency treatment, and radiofrequency ablation.11

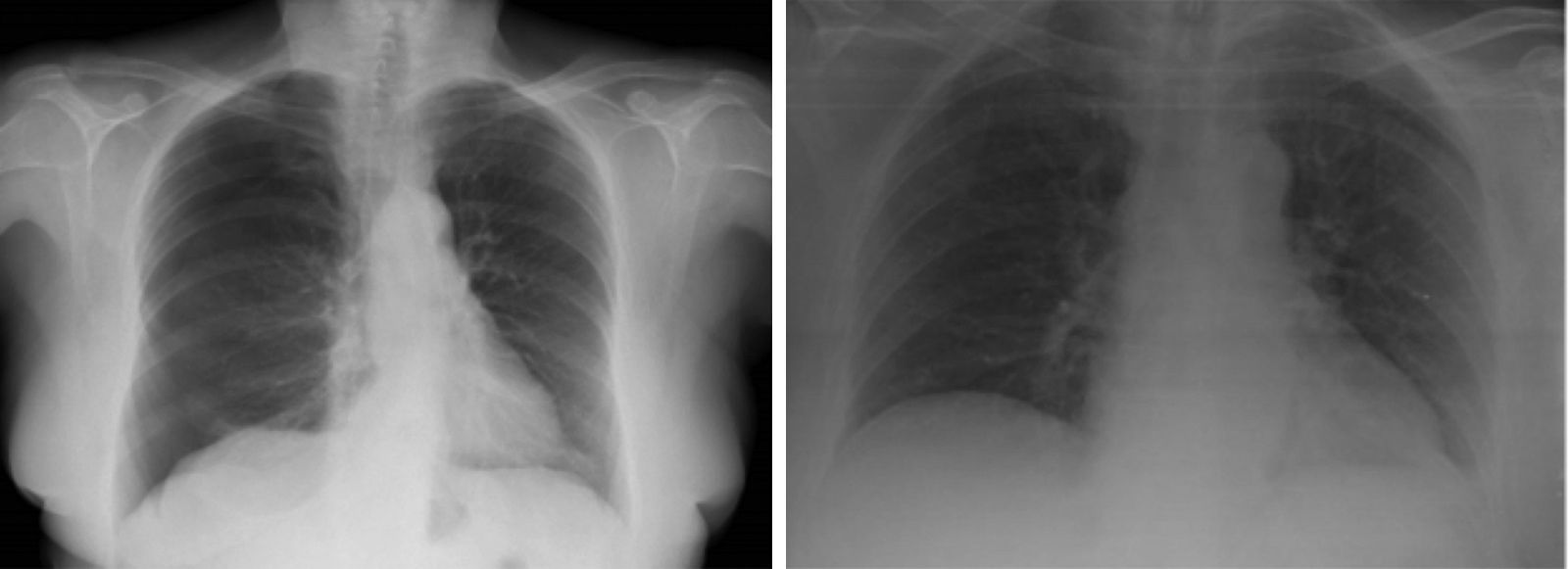

Given the scarcity of published scientific evidence for iatrogenic pneumothorax following the use of conventional radiofrequency, we present the case of a 62-year-old woman, with no toxic habits, diagnosed with fibromyalgia and osteoporosis, who developed postherpetic neuralgia as a late complication of thoracic herpes zoster infection in 2011. She had been monitored by the pain unit since 2012, and had received several treatments without success, including nerve block with local anesthetics and steroids in 2015. In April 2016, she began treatment with conventional intercostal radiofrequency, involving stimulation of the painful area above the right 9th intercostal space at 80° for 90s, without complications. A second incident-free radiofrequency session was conducted 12 weeks later, followed in December by a third conventional radiofrequency session at the 5th intercostal space. During this last session, the patient developed dyspnea, tachycardia 110bpm, and hypotension, so an emergency chest X-ray was performed, showing right pneumothorax (Fig. 1). A chest tube was placed, after which complete reexpansion of the right lung was observed. The patient was discharged from the pulmonology department 48h after the procedure with no complications.

Postherpetic neuralgia generally responds to drug therapy, and this should be used before any other intervention is attempted. Refractory cases can be treated with minimally invasive, though not entirely risk-free procedures such as nerve block, after which 0.09% of patients develop pneumothorax, a figure that rises to 0.42% if all patients are routinely given a chest X-ray.12 However, pneumothorax is not a common complication of radiofrequency techniques: no events were reported in larger series of up to 96 patients undergoing this treatment for postherpetic neuralgia.9

Radiofrequency is a minimally invasive intervention for the management of chronic pain, and its use in chronic pain units has been increasing in recent years.

The thoracic location of postherpetic neuralgia, in most cases, and the emergence of new techniques for pain control can lead to complications not initially considered, such as the case of our patient who presented pneumothorax in a healthy lung. The management of these cases begins with clinical suspicion, particularly in patients with risk factors. Treatment depends on the size of the pneumothorax. In the case of our patient, inter-procedural hemodynamic changes required urgent placement of a chest tube.

Despite their low incidence, facilities for the diagnosis and treatment of these complications must be available in these units, in the event that they do occur.

Please cite this article as: Cabrera César E, Fernández Aguirre MC, Vera Sánchez MC, Velasco Garrido JL. Neumotórax secundario a ablación por radiofrecuencia de neuralgia postherpética. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:47–48.