Ascaris lumbricoides (AL), popularly known as roundworm, is a nematode species belonging to the Ascarididae family, involved in the most common worldwide intestinal helminthic infection (Ascariasis).1 This nematode reaches gastrointestinal tract (GI) through ingestion of food/fluids contaminated with faeces, and in small intestine they migrate into pulmonary circulation, where they mature causing capillaries and alveolar walls destruction. Clinical presentation may vary from malaise, fever, loss of appetite, myalgia and headache to respiratory symptoms, which includes sputum-productive cough, chest pain, haemoptysis, shortness of breath and wheezing.1,2 Chest radiograph findings usually demonstrates peripherally basal opacities, although they can be present in different ways.3 An allergic response is responsible for the presence of respiratory symptoms and radiological manifestations, which can be seen as a transient nodular or diffuse pulmonary infiltrates (Loeffler's syndrome) or as a chronic eosinophilic pneumonia.1 However, spontaneous pneumothorax has also been described in literature in the context of Ascaris infection, but it constitutes a rare event.4 Here, we report a case of pneumothorax due to AL larvae in a young female.

A 26 years-old woman was admitted to Pulmonology Department in April 2018. Her past medical history included chronic rhinosinusitis, without other relevant pathological antecedents. She had no smoking history, allergies or previous surgeries, and no usual medication, drugs or alcohol consumption. No recent travel abroad or exposure to unpasteurized or uncooked foods. Patient resided in an urban area with good conditions, but had a non-dewormed cat at home.

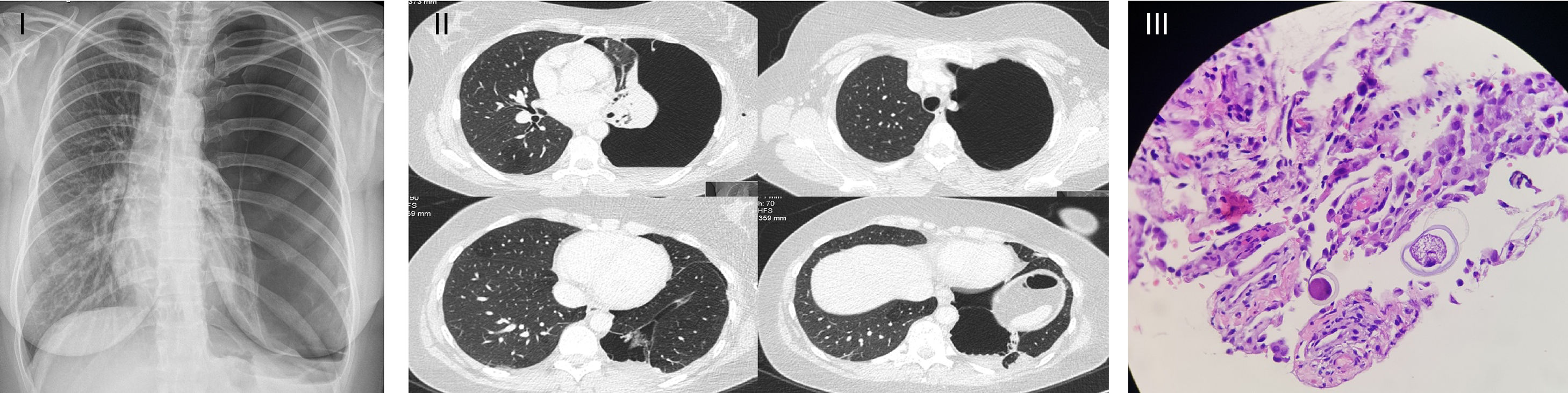

Patient had a history of exertional dyspnoea since February 2018, with no other relevant symptoms. Because of this, a chest X-ray was performed, and the diagnosis of a total left pneumothorax was made (Fig. 1I). Patient was then admitted to the emergency department where she was aware, collaborative and focused. Hydrated. Afebrile. Hemodynamically stable. No respiratory distress. SpO2 (FiO2 21%): 98%. At pulmonary auscultation: normal right sounds and decreased left sounds. Haematological and biochemical profiles, and arterial blood gas analysis (ABG) were normal. Thoracic drainage was placed at the fifth intercostal space, without complications. The presence of a high alveolar-pleural fistula debit was observed and lung expansion was not achieved. Chest computed-tomography-scan showed total collapse of the left lung, emphysema, densification areas and minimal pleural effusion (Fig. 1II). Bronchofibroscopy did not showed endobronchial lesions. Due to chest drainage failure, a video-assisted thoracoscopy surgery was performed, revealing a giant pulmonary bubble that was resected and several pleural implants were biopsied. Talc pleurodesis was also made. The expanded lung tissue showed a large number of eosinophils and scattered mesothelial fragments, consistent with an eosinophilic pleurisy. Histological examination showed an encysted AL (Fig. 1III). After surgery, a complete pneumothorax resolution was verified. Stool parasitology was negative, and the patient was treated with albendazole.

There was no recurrence of pneumothorax and haematological profile never revealed peripheral eosinophilia.

Lung parasitic infections can be present in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, and may affect respiratory system in different ways. AL is mainly seen in poor sanitation areas, where there is faecal contamination of soil or food. Disease transmission is faecal–oral.5

Most AL-infected patients do not have significant respiratory symptoms during larvae’ maturation or migratory phases, and its presence is a very uncommon finding, making this a rare cause of pneumothorax.

With increased travel and migration, parasitic lung and pleural diseases have raising in developed countries.5 Indeed, clinical presentations and radiographic findings of several of these infections may mimic respiratory diseases. For all this, it is essential to consider parasitic infections in the differential diagnosis of lung diseases.