Partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (PAPVC) encompasses a group of cardiovascular anomalies that are caused by the abnormal return of one or more of the pulmonary veins directly to the right atrium or indirectly through a variety of venous connections from the anomalous pulmonary veins.1,2

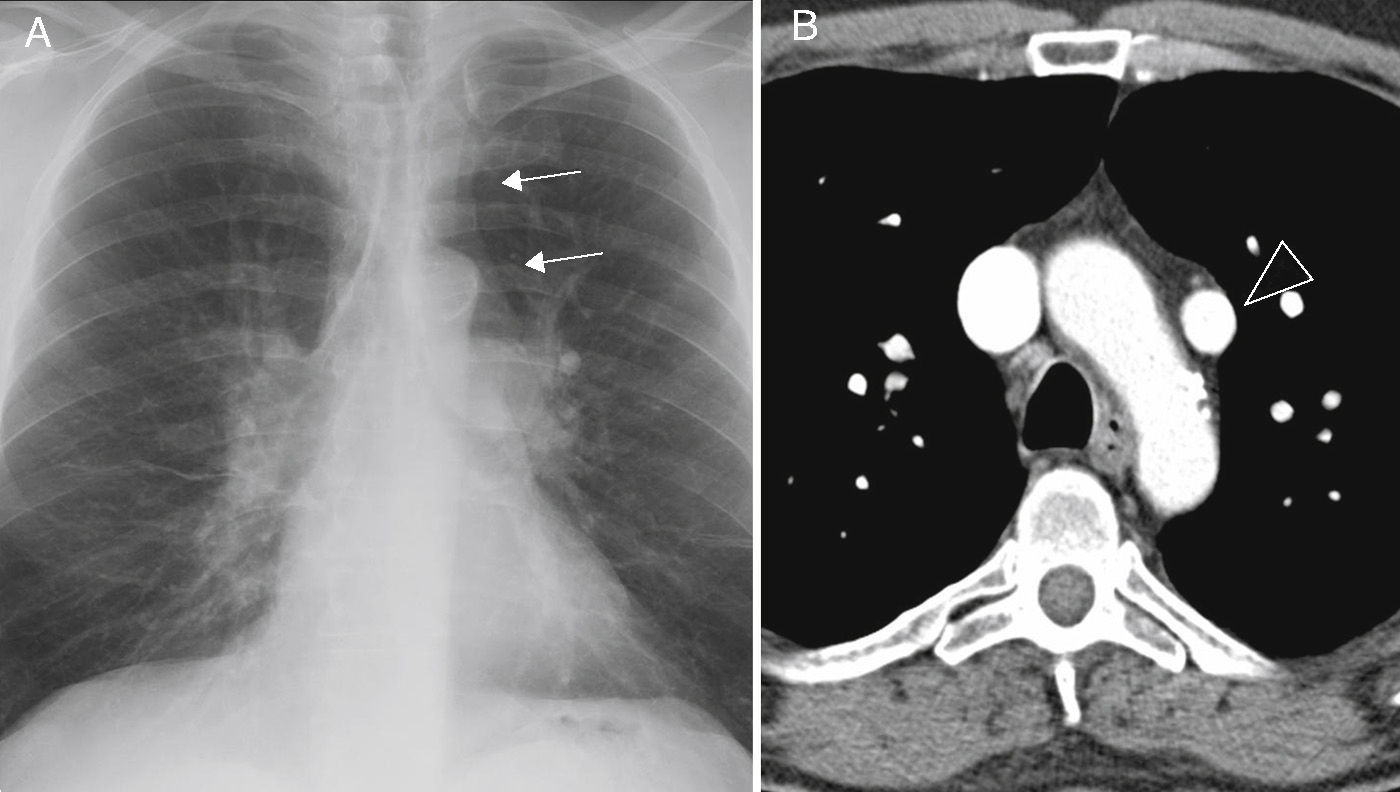

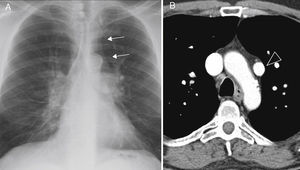

We present the case of a 51-year-old man, a former smoker, with a history of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and peripheral artery disease, who reported dyspnea on moderate exertion lasting several months. Laboratory test results (including serologic studies for hepatotropic viruses) were normal. Spirometry tests showed mild obstruction, and plethysmography and diffusing capacity measurements were normal. Chest radiography revealed enlargement of both hila and their vascular markings, with a double density sign on the left paratracheal area (Fig. 1A). The echocardiogram showed: normal left ventricle, right ventricle severely dilated, and indirect signs of pulmonary hypertension (PH). Right heart catheterization showed slight PH (mean PAP 29mmHg, total PVR 254.84dyn.s.cm−5). On computed tomography (CT) scan, an anomalous venous structure was seen in which the left pulmonary veins converged, draining into the brachiocephalic vein (Fig. 1B). Based on these findings, the patient underwent surgery (anastomosis of the defective left vein to the left atrium) and was discharged with antiplatelet therapy in addition to his usual medication. This improved his dyspnea. The follow-up echocardiogram at 3 years showed: normal left and right ventricle, no PH.

There are 2 types of PAPVC: partial anomalous pulmonary venous connections and partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage.1 In the first, an anomalous vein connects with a systemic vein, so that oxygenated blood from the pulmonary circulation mixes with the systemic venous blood, before draining into the right atrium; the most common form is drainage of the left upper pulmonary vein into the brachiocephalic vein. In the second, the pulmonary veins are correctly connected to the left atrium, but venous pulmonary blood flows into the right atrium or into both atria through a cardiac defect.

Although PAPVC can present as an isolated structural abnormality, it is often associated with other heart defects.2 The severity of symptoms depends on the extent of the left-right short circuit3 and the presence of other cardiac or pulmonary abnormalities. A preliminary diagnosis can be made with echocardiography and then confirmed with CT, magnetic resonance imaging or heart catheterization. Pulmonary angiography gives a more detailed anatomical image.

PAPVC must be treated surgically, although this can be avoided in asymptomatic patients with a minor short circuit.4 In some cases, even occlusion by catheterization can be considered.5 Prognosis for PAPVC patients is generally good.

Although these are congenital malformations, they can go unnoticed until adulthood. Given that up to 42.8% of PAPVC patients can present PH,2 clinicians should aware of the danger of diagnosing PAPVC patients with primary PH, since the therapeutic approach is very different in both cases.

Please cite this article as: Hernández Vázquez J, de Miguel Díez J, de Cortina Camarero C. Conexión venosa pulmonar anómala parcial con hipertensión pulmonar. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:153–154.