Dasatinib (Sprycel; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, USA) is a second generation, broad-spectrum tyrosine kinases inhibitor, and a potent effective drug for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).1 Use of this drug is, however, complicated by the occurrence of the specific adverse effect of pleural effusion.2

The incidence of pleural effusion associated with dasatinib differs according to the phase of the disease, the presence of comorbidities, and the dose or dose interval.2 Cortes et al. reported an overall incidence of pleural effusion occurring in 29% of CML patients receiving 100-mg dasatinibonce daily.1 Pleural effusion can also result in a need for supplemental oxygen or induce life-threatening conditions as a result of inducing hemodynamic or respiratory instabilityin approximately five percent of patients treated with dasatinib.1,2 Several mechanisms underlying the development of dasatinib-related pleural effusion, including the non-specific inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β or other molecules implicated in immune related pathways, have been proposed, but the exact mechanism remains unknown.3

We described a case of dasatinib-related pleural effusion that histologically resembled pleural nodular histiocytic hyperplasia (NHH).

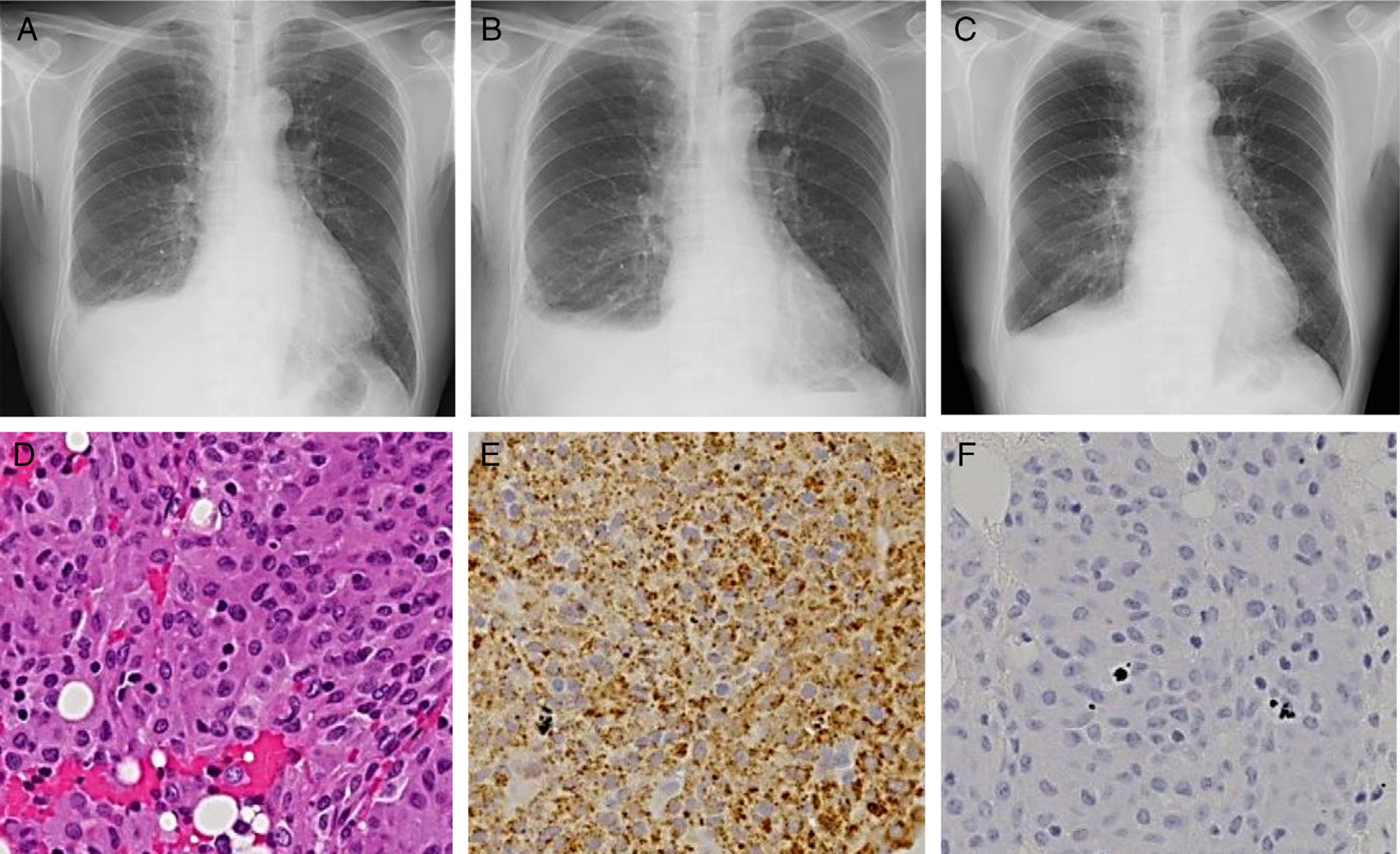

A 73-year-old man, an ex-smoker, was diagnosed with CML at 70 years of age. He was initially treated with 100-mg dasatinib once daily, but this dose was reduced to 70mg due to the development of thrombocytopenia. His medical history also included epilepsy and retroperitoneal fibrosis, the latter being treated with oral steroids from 68 to 70 years of age. About 2 months later, the patient complained of dyspnea upon exertion. His peripheral blood lymphocyte count was 59.1% (4200/μl), and the anti-nuclear antibody test was negative. The BCR/ABL1 fusion gene transcript count was less than 0.1% in peripheral blood, indicating that his CML was still in a major molecular response. A chest X-ray showed the presence of a right pleural effusion (Fig. 1A), and chest computed tomography revealed no evidence of any pleural thickening or involvement of the lung parenchyma. Analysis of the pleural effusion showed the presence of a lymphocyte-predominant (64%) exudate, 30.2U/L of adenosine deaminase, 1.37ng/mL of the carcinoembryonic antigen, and less than 100000mg/mL of hyaluronic acid. Cytology and culture of pleural fluid did not detect any malignancy or infective organisms. There was no isotope uptake in 67-gallium citrate scintigraphy.

Chest X-ray images at the first visit to our department (A), three weeks after pleural biopsy (B), and two weeks after interruption of dasatinib (C). Hematoxylin–eosin-stained microscopic image (D; 200× magnification) and immunohistochemical microscopic images with the antibodies against CD68 (E; 200×), and S-100 (F; 200×).

A pleural biopsy using video-associated thoracoscopy was performed to determine the nature of the pleural disease. Hematoxylin–eosin stained sections of the biopsy specimens showed the presence of aggregates of a homogenous cell population with eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 1D). Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the majority of cells expressed CD68 (Fig. 1E) but were negative for AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20, calretinin and CD34 antigens. The CD68-immunoreactive cells were also positive for vimentin but negative for S-100 protein (Fig. 1F) and desmin. These histologic and immunohistological results led to the diagnosis of NHH.

Additional pleural fluid had accumulated 3 weeks following the pleural biopsy (Fig. 1B). Dasatinib treatment was discontinued for 2 weeks, and an improvement of right pleural effusion was observed (Fig. 1C). No increase in the amount of pleural fluid was detected following the subsequent readministration of dasatinib.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a case of dasatinib-related pleural effusion diagnosed as pleural NHH using both histological and immunohistological studies.

We identified dasatinib to be the cause of the pleural effusion, as the level of pleural fluids was found to be dependent upon dasatinib treatment. Furthermore, the analysis of the pleural fluid was in keeping with previous reports. Comorbidities, including cardiac diseases, renal insufficiency, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and lymphocytosis (>3600/μl) are risk factors for the occurrence of dasatinib-related pleural effusions.4,5 Lymphocytosis was detected in the current case.

The pathogenesis of dasatinib-related pleural effusion is unknown. Only 2 studies have used pleural biopsies to investigate the cause.6,7 Bergeron et al. detected the presence of lymphocytic or myeloid infiltration in the pleura,6 while Ustun et al. reported the presence of organizing fibrinous pleuritis.7 Therefore, the current report is the first to diagnose pleural NHH.

NHH is a benign proliferative process composed predominantly of histiocytes, which show immunoreactivity against CD68.8,9 NHH may be a reactive process caused by a variety of situations, such as mechanical irritation, inflammation, and tumor.10 In the present case, there was no history of previous surgery, and the CML was in the major molecular response phase. Furthermore, no primary or metastatic carcinomas were detected in the pleural effusion and biopsies studies. We therefore considered NHH to be a possible cause of dasatinib-related pleural effusion in this patient. It is, however, possible that the NHH was a secondary event resulting from adasatinib-related pleural effusion. Future studies implementing the use of pleural biopsy are thus essential to examine the cause of dasatinib-related pleural effusion.

The management of dasatinib-related pleural effusion includes therapeutic thoracentesis, temporary interruption of dasatinib (as described in this report), and a short course of prednisone.2 Unfortunately, pleural effusion may be uncontrollable in a small percentage of dasatinib-treated patients.1,2 Further investigations are imperative to identify the mechanism underlying the development of pleural effusions to permit the optimal treatment of dasatinib-treated patients.

We thank Dr. Eiji Yamada for his comments regarding histopathologic findings.

Please cite this article as: Hamada S, Hayashi E, Tsukino M. ¿Es la hiperplasia histiocítica nodular una causa del derrame pleural asociado con el dasatinib? Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:212–213.