In urological oncology, the diagnosis of teratoma with a somatic-like malignant component refers to the presence of a malignant neoplasm, e.g. carcinoma or sarcoma, either within a teratoma of the genital tract (usually the testis) or, more commonly, in a metastasis, following initial cisplatin therapy.1 The somatic-type malignancy (STM) most widely observed in germ cell tumors (GCT) is rhabdomyosarcoma; neuroendocrine carcinoma is extremely rare.2

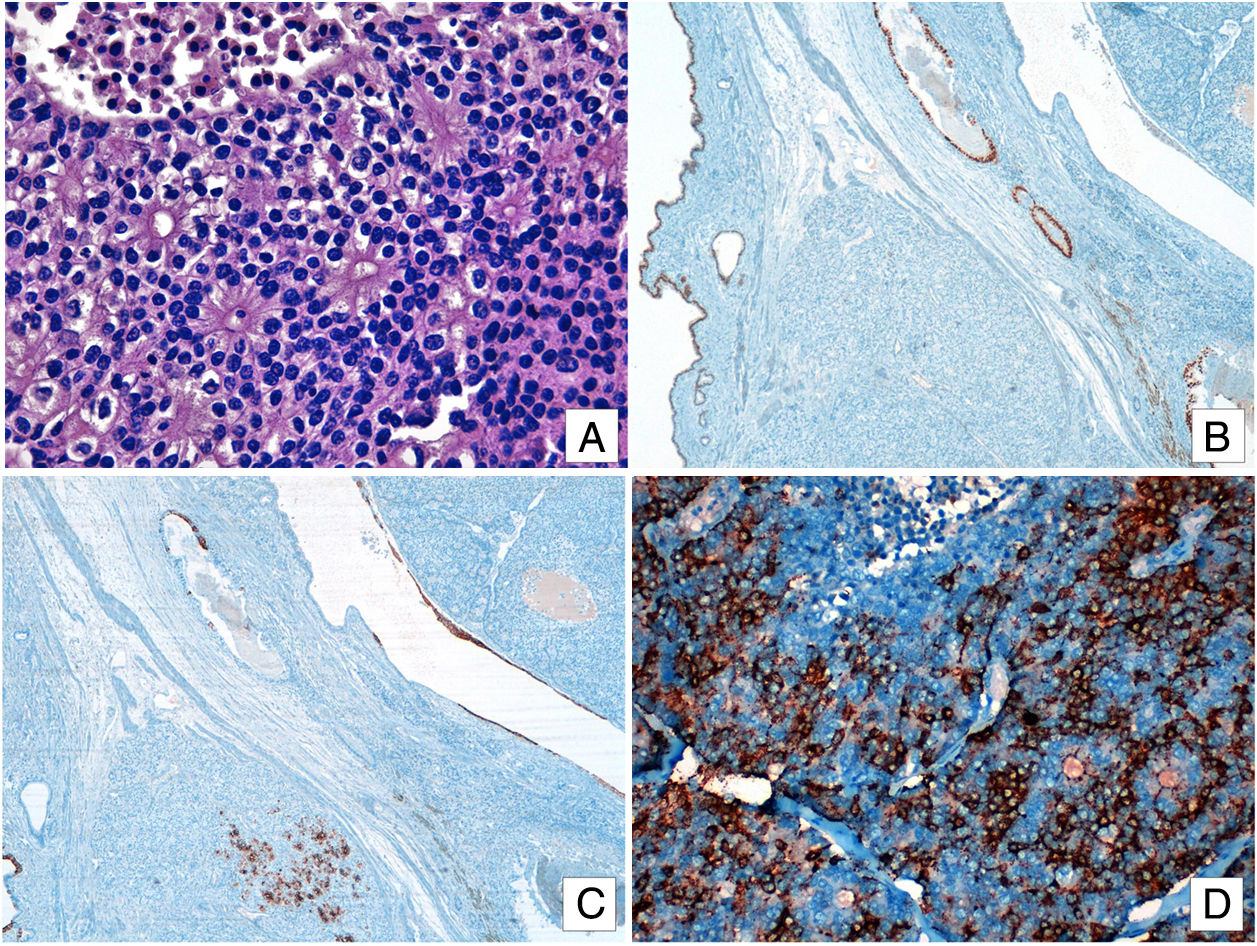

We report on a 40-year-old patient who had undergone surgery seven years earlier for a malignant mixed germ-cell tumor of the right testicle with pulmonary and retroperitoneal metastasis, and received cisplatin therapy. At recent check-up, CT scans revealed some enlargement of known lung lesions; blood alpha-fetoprotein levels were also slightly elevated (AFP: 9ng/ML). Since needle-biopsy findings were inconclusive, lung nodules were all excised by videothoracoscopy. Histological examination of them revealed a multicystic lesion containing solid areas. The cystic component was lined by squamous, respiratory and intestinal epithelium, a finding consistent with a mature teratoma. The solid component comprised tumor cell nests displaying peripheral pallisading, an organoid arrangement with rosette formation, focal necrosis and a high mitotic rate (6/10 HPF) (Fig. 1A). No elements characteristic of immature teratoma were observed. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed patchy focal positivity for CK7, CK20, CDX2 and SOX2 in the cylindrical epithelial cells of the cystic component (Fig. 1B and C). Solid-component cells stained positive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), chromogranin-A (Fig. 1D), synaptophysin, and cytoplasmic OCT4, and negative for CD56. Staining for neural development transcription factors (TTF1, ASCL1 and POU3F2) was positive only for POU3F2 (nuclear). Since tests using a broad battery of antibodies (CDX2, TTF1, CK7 and CK20) yielded negative results, it was not possible to identify the original tissue of the neuroendocrine component.

(A) Solid islets and cell clusters separated by a fibrous stroma. Cells display eosinophilic cytoplasm, rounded nuclei and fine granular chromatin. Metastatic lesion: Mature glandular tissue staining positive for CDX2 (B) and CK7 (C). (D) Tumor cells staining positive for chromogranin-A.

The final pathological diagnosis was atypical carcinoid tumor in a metastatic mature cystic teratoma. Surgical margins were tumor free, and postoperative recovery was good, with no complications.

Two histogenetic hypotheses have been put forward to account for this association. The first is that cisplatin therapy selectively excludes immature components, whilst chemotherapy-resistant mature components survive and in some cases grow. The second is that chemotherapy induces the transformation of immature malignant teratoma into mature teratoma, a phenomenon first reported by DiSaia et al. in ovarian GCTs, and termed chemotherapeutic retroconversion.3

Somatic-type malignancy occurs in 3–6% of GCTs, almost always in postpubertal patients (aged 15–68).1,2,4 Although most affected patients have teratomatous GCTs,1,2,5 somatic-type malignancy has occasionally been reported in other germ-cell tumors including yolk-sac and spermatocytic tumors.6 The time elapsing between GTC diagnosis and the appearance of STMs tends to vary widely, ranging from simultaneous presentation to a latency period of up to 30 years. The interval for carcinomas (108 months) is longer than for sarcomas (20 months).5

Reported STMs include various types of sarcoma, epithelial malignancies and hematological malignancies.7 Sarcomas are undoubtedly the most common type of malignancy; although rhabdomyosarcomas account for over half the STMs recorded, leiomyosarcomas, angiosarcomas and other STMs have occasionally been reported.8,9 Carcinomas tend to be mostly to be classed as adenocarcinomas NOS6; there are very few reports of neuroendocrine tumors, particularly in testicular lesions.

Generally speaking, the prognosis for these tumors is not affected when the STM is located in the testicle; however, development of STM in metastases—as in the present case—is associated with an increased risk of mortality.8

The role of chemotherapy in teratomas with malignant neuroendocrine transformation has not been fully established.7 Complete surgical resection has traditionally been the treatment of choice when malignant transformation occurs at a single site. Metastatic or unresectable tumors will generally require multimodal management including chemotherapy in addition to loco-regional approaches. Although patients tend to respond poorly to cisplatin-based treatments, some tumors may respond to the specific chemotherapy used for the somatic counterpart.10

Summarizing, in this rare case a patient with mixed germ-cell tumor of the testis and metastasis, treated with chemotherapy, seven years later developed an atypical carcinoid tumor, with a somatic-like malignant component, in a metastatic mature cystic teratoma of the lung. Comprehensive pathological examination is essential for the identification of somatic neoplasms within germ cell tumor metastases.