Uncontrolled donation after cardiac death (DACD) has become an alternative to lung transplantation with encephalic-death donation. The main objective of this study is to describe the incidence of clinically relevant events in the period of 30 days after lung transplant with uncontrolled DACD and the influence of factors depending on the donor and donation process as well.

Patients and methodsHistorical cohort study of 33 lung transplant receivers at Hospital Puerta de Hierro and Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla with 32 DACD from Hospital Clínico San Carlos from 2002 to 2008. We studied surgical and medical complications, primary graft dysfunction, acute rejection, pneumonia, and mortality. We made an evaluation of the donor characteristics and donation procedure times (min).

ResultsMedian age of recipients was 50.5 years (interquartile range, 38.5–58). There were 28 males and 5 females. Cumulative incidence of events in the first month was: pneumonia, 10 (31.3%); primary graft dysfunction, 15 (46.9%); rejection, 12 (37.5%); mortality, 4 (12.1%); medical complications, 25 (78.1%); and surgical complications, 18 (56.3%). Median time of cardiac arrest was higher in those who presented pneumonia (15 vs 7.5; P=.027). Median time of cold ischemia was higher in those who presented surgical complications and mortality (436 vs 343.5; P=.04; 505 vs 410; P=.033, respectively), and median of total ischemia times were longer in the recipients who died (828 vs 695; P=.036).

ConclusionsUncontrolled DACD is a valid alternative for expanding the donor pool in order to mitigate the current shortage of lungs that are valid for transplantation. The incidence of complications is comparable with published data in the literature.

La donación en asistolia no controlada (DANC) constituye una alternativa al trasplante pulmonar con donantes en muerte encefálica. El objetivo principal del estudio es describir la incidencia de eventos al mes tras el trasplante con pulmones de DANC, y la influencia de los factores dependientes del donante y del proceso de donación.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio de una cohorte histórica de 33 receptores de trasplante pulmonar realizados en los hospitales Puerta de Hierro y Marqués de Valdecilla con 32 DANC procedentes del Hospital Clínico San Carlos durante el periodo 2002-2008. Se estudiaron los siguientes eventos: complicaciones quirúrgicas y médicas, disfunción primaria del injerto, rechazo agudo, neumonía y mortalidad. Se evaluaron las características del donante y los tiempos del proceso de donación (minutos).

ResultadosLa mediana de edad de los receptores fue 50,5 años (rango intercuartílico, 38,5-58); 28 hombres y 5 mujeres. La incidencia acumulada de los eventos al mes fue: neumonía, 10 (31,3%); disfunción primaria del injerto, 15 (46,9%); rechazo, 12 (37,5%); mortalidad, 4 (12,1%); complicaciones médicas, 25 (78,1%), y quirúrgicas, 18 (56,3%). La mediana del tiempo de asistolia fue mayor en los sujetos con neumonía (15 vs 7,5; p=0,027), la mediana del tiempo de isquemia fría fue superior en los sujetos que presentaron complicaciones quirúrgicas y mortalidad (436 vs 343,5; p=0,04; 505 vs 410; p=0,033, respectivamente), y las medianas de los tiempos de isquemia total fueron superiores en los receptores que fallecieron (828 vs 695; p=0,036).

ConclusionesLos DANC constituyen una alternativa válida para expandir el pool de donantes pulmonares ante la carencia actual de pulmones válidos para el trasplante. La incidencia de complicaciones es comparable con los datos publicados en la literatura.

The good results obtained with transplantation programs worldwide have consolidated transplantation as a valid therapeutic option in a multitude of diseases. The increase in indications has created disparity between the supply and demand, as the number of indications is greater than the number of organs available, even despite the increase in donations.1 In Spain, on 31 December 2008, there were 175 recipients awaiting lung transplantation. During the year of 2008, the waiting list had gone from 133 to 175 patients, with an approximate overall mortality of 4.6%, in spite of having performed 192 lung transplantations.1 Given this problem and the consequent limited number of organs, expanded criteria donors (ECD) have come about.2,3

Among the different types of ECD, there is a group, that of cardiac death (CD) or non-heart-beating (NHB) donors, that is being developed in many countries due to the good results obtained with the transplantation of organs from these donors.4–7 Given the scarcity of lungs available for transplantation, transplantation programs with lungs coming from CD donors are being given more consideration.8–13

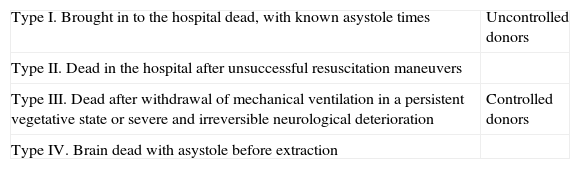

In 1995 in Maastricht, CD donations were classified into two large groups: controlled and uncontrolled donation after cardiac death (DACD) (Table 1).14 The lung transplantations coming from uncontrolled DACD became possible after the studies by Steen et al. in 2001.15

Maastricht Classification for Donors After Cardiac Death.

| Type I. Brought in to the hospital dead, with known asystole times | Uncontrolled donors |

| Type II. Dead in the hospital after unsuccessful resuscitation maneuvers | |

| Type III. Dead after withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in a persistent vegetative state or severe and irreversible neurological deterioration | Controlled donors |

| Type IV. Brain dead with asystole before extraction |

In Spain, the CD donation programs are mostly with uncontrolled patients (Maastricht types I and II) or with type IV controlled donors (cardiac arrest during the management of a brain-death donor). The donations with organs coming from type III donors are scarce; however, these are the most common types of non-heart-beating donor in the rest of the world.8–10

The Hospital Clínico and Hospital Puerta de Hierro have created a specific pioneering lung transplantation program with uncontrolled DACD. These lung transplantations started in 2002, and the results published up until now, after an evaluation of the functionality and viability of these grafts,11 have centered around the description of the mid-term experience of the first 17 cases.12 In this paper, after 6 years of experience and a greater sample size of the series, we present the results and describe the incidence of events 30 days post-transplantation with uncontrolled DACD lungs and the influence of the factors according to the donor and donation process.

Patients and MethodsOurs is a historical cohort of patients with lung transplantation from January 2002 until December 2008 at the Hospital Puerta de Hierro (HPH) in Madrid and Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla (HMV) in Santander, with organs from the Hospital Clínico San Carlos (HCSC) in Madrid.

The inclusion criteria of the study were: uncontrolled non-heart-beating donors of an organ and/or tissue at HCSC, who became real donors (those in whom the organs and/or tissues are offered to the National Transplant Organization as being valid for implantation in a recipient) and all the recipients of lungs from non-heart-beating donors.

The exclusion criteria of the study were: CD during the study period in which the organs and/or tissues were unacceptable for donation.

Uncontrolled DACD, the cornerstone of the Hospital Clínico program in Madrid, requires a process for selecting donors and obtaining organs that is rigorous and complex, as has been previously published.11,12,16 The following is a summary of the criteria:

- 1.

Patients who have had a witnessed cardiac arrest outside hospital and have cardiopulmonary resuscitation by CPR-trained providers commenced within 10min.

- 2.

Age between 7 and 50.

- 3.

Preservation maneuvers started (femorofemoral bypass with extracorporeal circulation and membrane oxygenation [ECMO] and deep hypothermia at 4°C+specific lung preservation maneuvers) in less than 120min from the onset of CPR (warm ischemia time).

- 4.

Family and judicial consent.

- 5.

Specific lung preservation maneuvers: after the establishment of the extracorporeal circulation and cessation of the mechanical ventilation, placement of four thoracic drains and perfusion through these of 4l of Perfadex® solution at 4°C in each hemithorax to achieve lung collapse. The lungs can be maintained in this situation for a maximum of 240min (preservation limit time).

- 6.

Validation of the organ by means of: a) emptying both hemithorax and reinstating mechanical ventilation (FiO2, 1; PEEP, +5cm H2O); b) evaluation of the macroscopic lung appearance; c) conformation of the integrity and quality of the airway using bronchoscope; d) cannulation of the pulmonary artery and of each of the 4 pulmonary veins; e) flushing from the artery to the pulmonary veins with Perfadex® preservation solution until a clear effluent is obtained in the left auricle and pulmonary veins; and f) circulation of 300ml of blood previously obtained from the donor himself/herself (during cannulation to set up the bypass) to which PgE is added from the artery to pulmonary veins, carrying out gasometric determination at both levels (correction of PaO2 depending on the temperature). If the difference of PaO2 between pulmonary artery and veins is greater than 300mmHg, the lung is considered valid for transplantation.

- 7.

Removal, preservation and implantation of the organ according to standard protocols. Period of cold ischemia, in which the organ is maintained in a sterile cold preservation solution in a refrigerator.

- 8.

Ischemia time was established as already mentioned. Other exclusion criteria included: pathological chest radiography upon the patient's arrival to the hospital; the presence of blood or purulent secretions in the orotracheal tube; the presence of exsanguinating chest trauma ruling out CPR; clinical suspicion for bronchoaspiration or active respiratory infection and the general exclusion criteria for lung donors and donation after cardiac death.

The protocols for immunosuppression and rejection control, as well as antibiotic prophylaxis, were those of both hospitals, applied to lung transplant recipients.

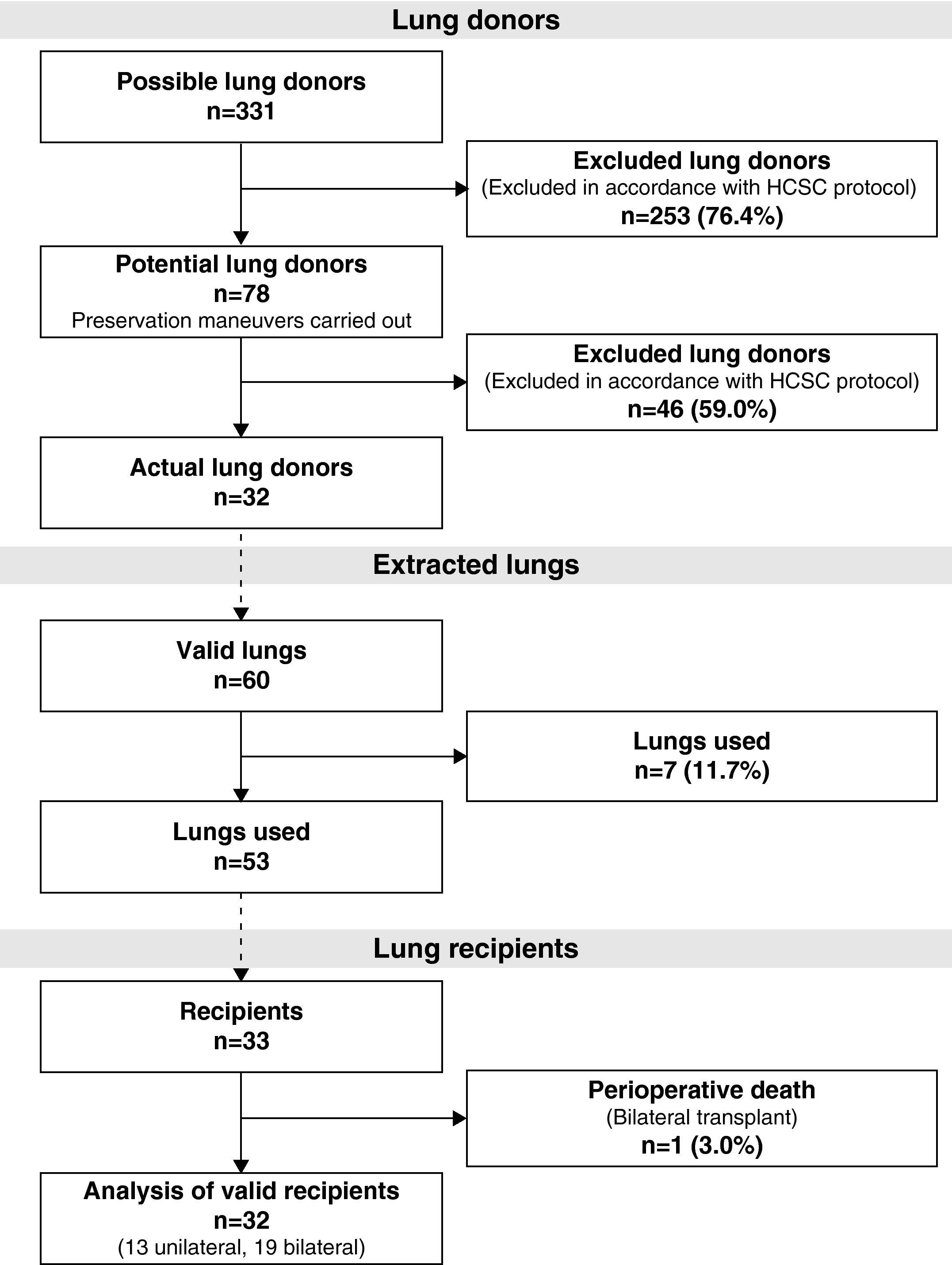

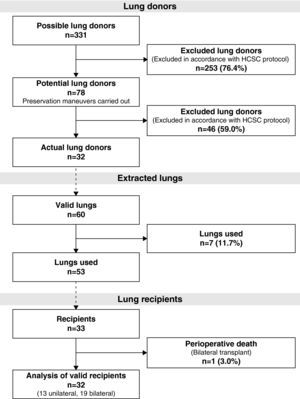

During the study period, 331 potential lung donors were evaluated, out of which 32 became actual donors in the end. Fifty-three lungs were implanted in 33 recipients. We performed 20 bilateral lung transplantations (16 at HPH and 4 at HMV) and 13 unilateral lung transplantations (12 at HPH and 1 at HMV) (Fig. 1).

The study variables were selected prospectively through the databases of each of the centers.

The main result variables of the study in the recipients, evaluated at one month follow-up, were: surgical complications (presence of one of the following: bronchial suture dehiscence, sternal suture dehiscence, tracheal stenosis, bronchomalacia, hemothorax, bronchial fistulas, pneumothorax, phrenic paralysis, infection of the surgical wound), medical complications (presence of one of the following: renal, digestive, metabolic, neurologic, arrhythmia and leucopenia), primary graft dysfunction (PGD); grades G2 and G3),17 acute rejection, pneumonia, and mortality.

We identified two groups of independent variables that were related with each of the result variables, the characteristics of the donor (cause of death, age, sex, tobacco habit, clinical diagnosis of ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and arterial hypertension [HTN]) and of the donation process (asystole time [AT], cardiac arrest time [CAT], warm ischemia time [WIT], preservation time [PT], cold ischemia time [CIT], and total ischemia time [TIT]). In the cases of bilateral lung transplants, the maximum value between the two lungs was used for the calculation of the CIT and TIT.

The following characteristics were registered for the description of the receptors: age, sex, time on the waiting list, need for pre-transplant mechanical ventilation, mean ICU or hospital stay, and disease indicating transplant.

Statistical AnalysisThe qualitative variables are presented with their distribution of frequencies and the quantitative variables are summarized with their mean and standard deviation (SD) or with the median and interquartile range (IR) in cases with abnormal distributions. We evaluated the association between the qualitative variables with the χ2-test or with Fisher's exact test if more than 25% of the predicted frequencies were less than 5. The relative risk (RR) was estimated together with its 95% confidence interval (CI) for the evaluation of the correlation between the donor characteristics and each of the result variables. We analyzed the relationship of the quantitative variables of the study with each of the result variables by means of the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. For all these tests, the accepted level of significance was 5%. The analysis of the data was done with the SPSS version 15.0 statistical package for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, United States).

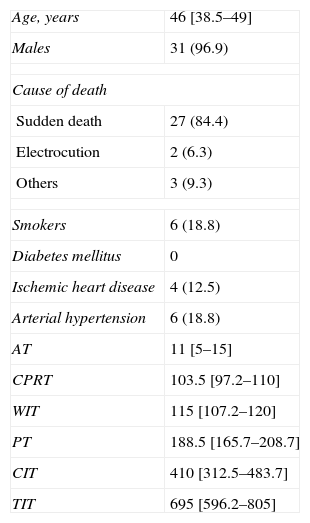

ResultsOut of the 331 potential lung donors evaluated in the HCSC, 32 became actual lung donors, and their lungs were implanted in 33 recipients. The average age of the donors was 46 (IR, 38.5–49). The main cause of death was sudden cardiac death (84.4%). Out of the 32 donors, 31 were men and 1 woman. The specific characteristics of the donors and of the donation process times are compiled in Table 2. Pathogens were found in the donor lungs on three occasions, with positive cultures for Candida crusei, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catharralis. The recipients were treated with no incidences in any of these cases.

Clinical Characteristics of the Donors (n=32) and of the Donation Process Times (min).

| Age, years | 46 [38.5–49] |

| Males | 31 (96.9) |

| Cause of death | |

| Sudden death | 27 (84.4) |

| Electrocution | 2 (6.3) |

| Others | 3 (9.3) |

| Smokers | 6 (18.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 4 (12.5) |

| Arterial hypertension | 6 (18.8) |

| AT | 11 [5–15] |

| CPRT | 103.5 [97.2–110] |

| WIT | 115 [107.2–120] |

| PT | 188.5 [165.7–208.7] |

| CIT | 410 [312.5–483.7] |

| TIT | 695 [596.2–805] |

AT: asystole time; WIT: warm ischemia time; CIT: cold ischemia time; TIT: total ischemia time; PT: preservation time; CPRT: cardiopulmonary resuscitation time.

The data express n (%) or mean [interquartile range].

As for the recipients, the mean age was 50.5 (IR, 38.5–58); 28 were men and 5 women. The average time on the waiting list of the recipients was 150 days (IR, 42–254). None of the recipients was receiving invasive mechanical ventilation before the transplantation, but 12.1% were receiving non-invasive mechanical ventilation.

The causes that indicated the transplant in the recipients were COPD (45.4%), cystic fibrosis (15.1%), idiopathic lung fibrosis (33.3%), sarcoidosis (3.1%), and COPD+pulmonary fibrosis (3.1%).

Mean ICU stay was 10 days (IR, 7–23) and mean hospitalization was 34.5 days (IR, 26.5–59.7). The mean intubation time was 48h (IR, 36–144). In 10, reintubation was required, while tracheostomy was necessary in 15 (days of ICU stay: 21; IR, 16–49).

The incidence of each of the result variables after one month in the 32 recipients was: pneumonia (31.3%; 95% CI, 16.1–50), primary graft dysfunction (46.9%; 95% CI, 28–65.7), rejection (37.5%; 95% CI, 21.1–56.3), medical complications (78.1%; 95% CI, 60–90.7), surgical complications (56.3%; 95% CI, 37.7–73.6), and mortality (12.1%; 95% CI, 3.4–28.2). Among the receptors who developed PGD, 4 presented G1, 6 recipients presented G2, and 9 presented G3. For the calculation of the incidence of mortality, we used the number of receptors as a denominator (n=33).

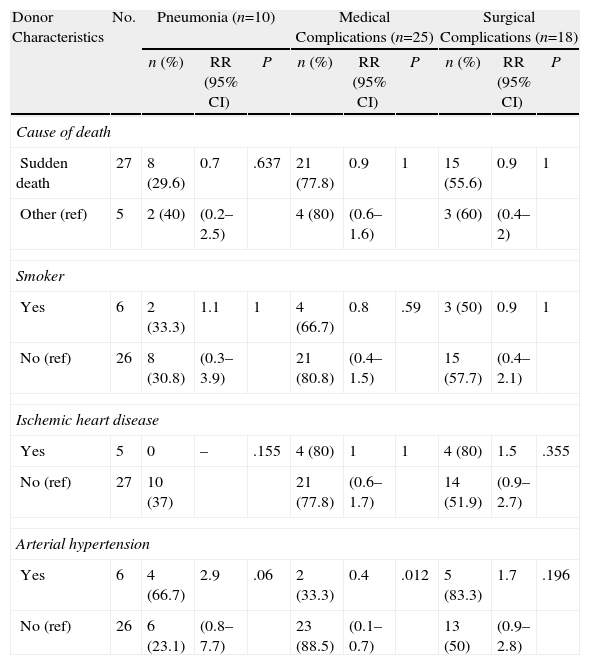

Tables 3–6 show the results of the univariate analysis of the factors from the donor study and the times of the donation process with each of the clinical result variables evaluated after one month's follow-up. The variables related with the analysis of the times that showed statistically significant differences were the mean AT for the pneumonia variable (P=.027) and the mean CIT for the surgical complication variable (P=.04), being higher in those who developed pneumonia and surgical complications. The medians of CIT (P=.033) and TIT (P=.036) were greater in the recipients who died during the first month after the transplant.

Correlation of the Donor Characteristics With the Development of Pneumonia, Medical and Surgical Complications Within One Month.

| Donor Characteristics | No. | Pneumonia (n=10) | Medical Complications (n=25) | Surgical Complications (n=18) | ||||||

| n (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | n (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | n (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Cause of death | ||||||||||

| Sudden death | 27 | 8 (29.6) | 0.7 | .637 | 21 (77.8) | 0.9 | 1 | 15 (55.6) | 0.9 | 1 |

| Other (ref) | 5 | 2 (40) | (0.2–2.5) | 4 (80) | (0.6–1.6) | 3 (60) | (0.4–2) | |||

| Smoker | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 2 (33.3) | 1.1 | 1 | 4 (66.7) | 0.8 | .59 | 3 (50) | 0.9 | 1 |

| No (ref) | 26 | 8 (30.8) | (0.3–3.9) | 21 (80.8) | (0.4–1.5) | 15 (57.7) | (0.4–2.1) | |||

| Ischemic heart disease | ||||||||||

| Yes | 5 | 0 | – | .155 | 4 (80) | 1 | 1 | 4 (80) | 1.5 | .355 |

| No (ref) | 27 | 10 (37) | 21 (77.8) | (0.6–1.7) | 14 (51.9) | (0.9–2.7) | ||||

| Arterial hypertension | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 2.9 | .06 | 2 (33.3) | 0.4 | .012 | 5 (83.3) | 1.7 | .196 |

| No (ref) | 26 | 6 (23.1) | (0.8–7.7) | 23 (88.5) | (0.1–0.7) | 13 (50) | (0.9–2.8) | |||

CI: confidence interval; ref: reference category for the calculation of RR; RR: relative risk.

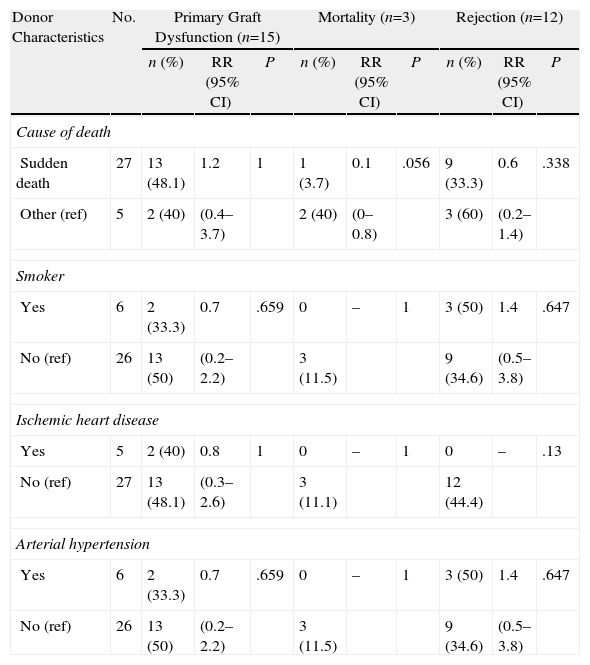

Correlation of the Donor Characteristics With Primary Graft Dysfunction, Mortality, and Rejection in the First Month.

| Donor Characteristics | No. | Primary Graft Dysfunction (n=15) | Mortality (n=3) | Rejection (n=12) | ||||||

| n (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | n (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | n (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Cause of death | ||||||||||

| Sudden death | 27 | 13 (48.1) | 1.2 | 1 | 1 (3.7) | 0.1 | .056 | 9 (33.3) | 0.6 | .338 |

| Other (ref) | 5 | 2 (40) | (0.4–3.7) | 2 (40) | (0–0.8) | 3 (60) | (0.2–1.4) | |||

| Smoker | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 2 (33.3) | 0.7 | .659 | 0 | – | 1 | 3 (50) | 1.4 | .647 |

| No (ref) | 26 | 13 (50) | (0.2–2.2) | 3 (11.5) | 9 (34.6) | (0.5–3.8) | ||||

| Ischemic heart disease | ||||||||||

| Yes | 5 | 2 (40) | 0.8 | 1 | 0 | – | 1 | 0 | – | .13 |

| No (ref) | 27 | 13 (48.1) | (0.3–2.6) | 3 (11.1) | 12 (44.4) | |||||

| Arterial hypertension | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 2 (33.3) | 0.7 | .659 | 0 | – | 1 | 3 (50) | 1.4 | .647 |

| No (ref) | 26 | 13 (50) | (0.2–2.2) | 3 (11.5) | 9 (34.6) | (0.5–3.8) | ||||

CI: confidence interval; ref: reference category for the calculation of RR; RR: relative risk.

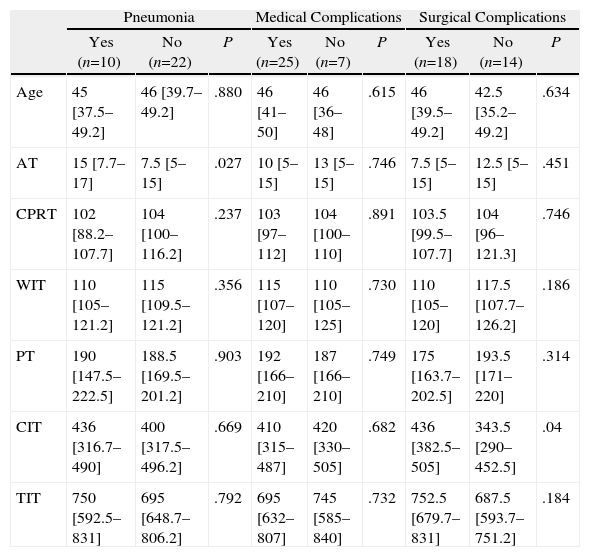

Donation Processing Time (min) and the Presence of Pneumonia and Medical or Surgical Complications Within One Month.

| Pneumonia | Medical Complications | Surgical Complications | |||||||

| Yes (n=10) | No (n=22) | P | Yes (n=25) | No (n=7) | P | Yes (n=18) | No (n=14) | P | |

| Age | 45 [37.5–49.2] | 46 [39.7–49.2] | .880 | 46 [41–50] | 46 [36–48] | .615 | 46 [39.5–49.2] | 42.5 [35.2–49.2] | .634 |

| AT | 15 [7.7–17] | 7.5 [5–15] | .027 | 10 [5–15] | 13 [5–15] | .746 | 7.5 [5–15] | 12.5 [5–15] | .451 |

| CPRT | 102 [88.2–107.7] | 104 [100–116.2] | .237 | 103 [97–112] | 104 [100–110] | .891 | 103.5 [99.5–107.7] | 104 [96–121.3] | .746 |

| WIT | 110 [105–121.2] | 115 [109.5–121.2] | .356 | 115 [107–120] | 110 [105–125] | .730 | 110 [105–120] | 117.5 [107.7–126.2] | .186 |

| PT | 190 [147.5–222.5] | 188.5 [169.5–201.2] | .903 | 192 [166–210] | 187 [166–210] | .749 | 175 [163.7–202.5] | 193.5 [171–220] | .314 |

| CIT | 436 [316.7–490] | 400 [317.5–496.2] | .669 | 410 [315–487] | 420 [330–505] | .682 | 436 [382.5–505] | 343.5 [290–452.5] | .04 |

| TIT | 750 [592.5–831] | 695 [648.7–806.2] | .792 | 695 [632–807] | 745 [585–840] | .732 | 752.5 [679.7–831] | 687.5 [593.7–751.2] | .184 |

AT: asystole time; WIT: warm ischemia time; CIT: cold ischemia time; TIT: total ischemia time; PT: preservation time; CPRT: cardiopulmonary resuscitation time.

The data express means [interquartile range].

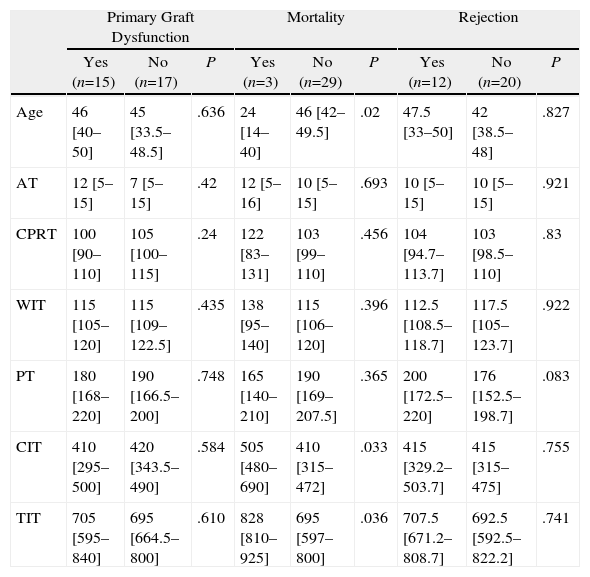

Donation Processing Times (min) and Presence of Primary Graft Dysfunction, Mortality, and Rejection Within the First Month.

| Primary Graft Dysfunction | Mortality | Rejection | |||||||

| Yes (n=15) | No (n=17) | P | Yes (n=3) | No (n=29) | P | Yes (n=12) | No (n=20) | P | |

| Age | 46 [40–50] | 45 [33.5–48.5] | .636 | 24 [14–40] | 46 [42–49.5] | .02 | 47.5 [33–50] | 42 [38.5–48] | .827 |

| AT | 12 [5–15] | 7 [5–15] | .42 | 12 [5–16] | 10 [5–15] | .693 | 10 [5–15] | 10 [5–15] | .921 |

| CPRT | 100 [90–110] | 105 [100–115] | .24 | 122 [83–131] | 103 [99–110] | .456 | 104 [94.7–113.7] | 103 [98.5–110] | .83 |

| WIT | 115 [105–120] | 115 [109–122.5] | .435 | 138 [95–140] | 115 [106–120] | .396 | 112.5 [108.5–118.7] | 117.5 [105–123.7] | .922 |

| PT | 180 [168–220] | 190 [166.5–200] | .748 | 165 [140–210] | 190 [169–207.5] | .365 | 200 [172.5–220] | 176 [152.5–198.7] | .083 |

| CIT | 410 [295–500] | 420 [343.5–490] | .584 | 505 [480–690] | 410 [315–472] | .033 | 415 [329.2–503.7] | 415 [315–475] | .755 |

| TIT | 705 [595–840] | 695 [664.5–800] | .610 | 828 [810–925] | 695 [597–800] | .036 | 707.5 [671.2–808.7] | 692.5 [592.5–822.2] | .741 |

AT: asystole time; WIT: warm ischemia time; CIT: cold ischemia time; TIT: total ischemia time; PT: preservation time; CPRT: cardiopulmonary resuscitation time.

The data express means [interquartile range].

With regards to the medical history of the donors, a relationship has been found between the presence of medical complications in the recipient and a history of HTN in the donor (RR=0.4; 95% CI, 0.1–0.7; P=.012). HTN also presented an association with the development of pneumonia (P=.06), with a risk almost 3 times greater in the recipients of lungs coming from donors with HTN after cardiac death (RR=2.9; 95% CI, 1.2–7.1).

As for the 30-day post-transplant mortality, a correlation was found with age (P=.02) and with the cause of death of the donor (P=.056). Sudden death was a protective factor (RR=0.1; 95% CI, 0.0–0.8), while a younger mean age was seen among the donors whose lung recipients had died within the first month port-op. In the rest of the factors evaluated, no statistically significant associations were found.

DiscussionOne of the most important causes for the low rate of organs being obtained from brain-death donors (BDD) is due to the inevitable ICU stay of patients who develop brain death and to the also inevitable need for mechanical ventilation.16 An uncontrolled DACD is a donor who does not go through a prolonged period of ventilation. Instead, the maximum is 120min, with a low risk of colonization/infection and pulmonary barotrauma/volutrauma. This all favors a high rate of valid lungs obtained for transplantation after donor selection (41% in controlled DACD compared with 10%–15% of BDD).1

The results in the first post-transplantation month, which are those that are more directly related with the factors dependent on the donor, method of selection and organ preservation, are within the ranges published in the literature. The incidence of PGD in BDD and controlled DACD varies between 10% and 49%18–21 and between 25% and 40%,10,13,22 respectively. The definitions of PGD in these studies are not homogeneous in either appearance time or categorization, which makes their direct comparison difficult. The ranges of acute rejection oscillate between 9% and 45%20,23 in BDD and between 0% and 50% in controlled DACD.10,13,22,24 In BDD, the mortality varies between 10% and 19%,19–21,25 while in controlled DACD the studies published do not report any deaths within the first month. These studies that do not present events of mortality and acute rejection are series with small sample sizes.

Both the medical as well as the surgical complications presented high incidences; however, it is difficult to compare these data with the literature due to the different ways of categorizing the complications in the different studies.

Given the results of this study, the only variables that are significant for the presence of surgical and/or medical complications immediately after transplantation are the presence of arterial hypertension in the donor and cold ischemia time. We have not found references in the medical literature regarding the influence of HTN on post-op complications. As for cold ischemia time, its influence on different surgical complications is controversial.26,27 The distribution of the risk factors for developing pneumonia was studied between the recipients of lungs from donors with and without HTN, obtaining a greater intubation time in the HTN group. In our series, a greater intubation time was significantly related with the development of pneumonia (data not shown). This finding could explain the relationship found between the HTN of the donor and the development of pneumonia; however, it would be necessary to study this relationship in series with greater sample sizes, where we could control for potentially confounding factors through a multivariate analysis, and thus determine the independent effect of each.

There is a significant relationship between asystole time (despite normal radiology and absence of suspicion for bronchoaspiration) and the development of pneumonia in the recipient within the first month, although the evolution was good in these cases. There is a tendency towards an association between the presence of HTN in the donor and the presence of pneumonia during the first month. The rest of the specific characteristics of uncontrolled DACD do not seem to represent a risk for the development of pneumonia.

In the present study, we have not found a relationship between the donor characteristics or the process of donation and the presence of rejection or PGD, which agrees with the series published with regards to rejection28; however, in the literature, risk factors have been reported for the development of PGD, such as age, history of tobacco use, diabetes, and prolonged ischemia times in BDD that no not seem to have an influence on the results of the lungs from uncontrolled DACD.20,29

As for mortality in the 30 days after transplantation, we have found a statistically significant relationship between this and the times for cold and total prolonged ischemia. In the literature, some studies indicate that the increased ischemia time in lung transplantation has a negative impact on the mortality of the recipient30; however, in other studies this is not confirmed.31 Among the donor factors that can influence one-month mortality, we found age and cause of death. The donors of recipients who died within the postoperative month presented lower ages compared with those who did not die. These data are striking, as in different studies that associate the mortality of the recipient with the age of the donor, higher age intervals are associated with mortality.32,33 The lungs of the younger donors presented higher cold ischemia and total ischemia times, variables that are related in our study with mortality within one month post-transplant (data not shown).

The cause of death of the donors presents a tendency towards association. Sudden death seems to be a protective factor for the development of one-month mortality. This finding is not confirmed in other series.32 The results for mid to long-term survival have already been published as good.11,12

One of the main limitations of the present study is the small sample size analyzed, as it is a follow-up of a small clinical cohort of lung transplant recipients. The small sample size leads to a loss of statistical power, of precision in the estimations analyzed and in capacity to generalize the results. We think that, despite the limited sample size and due to the fact that there are currently not many series published and the low rate of lungs acquired from BDD, the results of the present study help us understand the incidence of events within one month post-transplant and the possible associated factors.

Donation after cardiac death constitutes a valid alternative for expanding the lung donor pool with the current situation of lack of valid organs for transplantation.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez DA, et al. Trasplante de pulmón con donantes no controlados a corazón parado. Factores pronósticos dependientes del donante y evolución inmediata postrasplante. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:403–9.