Klebsiella pneumoniae is a gram-negative bacterium that forms part of the intestinal flora of healthy people. It occasionally causes community-acquired infection in patients with risk factors, and more frequently nosocomial urinary and respiratory infections. In 1986, Liu et al. described a new syndrome caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), consisting of a liver abscess associated with septic endophthalmitis, a severe and invasive condition caused by capsular serotypes K1 or K2, associated with a phenotype of hypermucoviscosity and hypervirulence called K. pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome (KLAS)1. In 2004, Fang et al. identified the new magA gene in isolates of a new hypervirulent KLAS microorganism, the main characteristic of which is to cause serious infection in young, immunocompetent individuals2. We report the case of a patient with KLAS associated with severe bilateral bronchopneumonia, a process rarely described in our country.

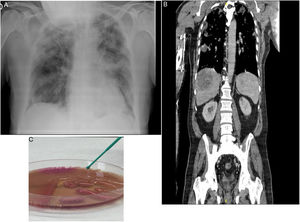

Our patient was a 70-year-old man from Algeria, resident in Spain, who had not recently traveled, former smoker of 16 pack-years, type 2 diabetic, with chronic ischemic heart disease and no history of respiratory disease, receiving atenolol, ramipril and metformin. He attended the emergency department due to a 3-day history of fever, nausea, and right pleuritic pain. Examination revealed: fairly poor general condition; tachypnea at 22 breaths/min; O2 delivered by nasal cannulae at 4 l/min; SaO2 95%; blood pressure 100/50 mmHg; heart rate 85 bpm; temperature of 39 °C; pulmonary auscultation: crackles reaching the bilateral mid-lung fields. A chest X-ray was performed in which peripheral infiltrates were observed in both hemithoraces, consistent with bronchopneumonia Fig. 1A).

Additional emergency tests showed arterial blood gases (FiO2 0.21); pH 7.44, PaCO2 31 mmHg, PaO2 53 mmHg, HCO3 20.9 mmol/l, PaO2/FiO2 252. Blood tests showed leukocytes 8,310/ml, neutrophils 77%, lymphocytes 8.1%; RBCs 4,100,000/ml; hemoglobin 12.2 g/dl; hematocrit 33%; platelets 119,000/ml; Quick 68%; D-dimer 1,772 ng/ml, glucose 280 mg/dl, urea 42 mg/dl; creatinine 1.46 mg/dl; albumin 2.40 g/dl; sodium 130 mmol/l; potassium 3.50 mmol/l; ALT 143 U/l; LDH 281 U/l; C-reactive protein > 25 mg/dl. Urine sediment was normal. PCR for SARS CoV-2 was negative. At 48 h, blood cultures showed growth of multisensitive K. pneumoniae. Urine culture and antigenuria for Legionella and pneumococci were negative. At 24 h, the patient presented hypotension, increased tachypnea, temperature of 38 °C and radiological deterioration, with patchy infiltrates progressing bilaterally. Thoracoabdominal CT showed bilateral pleural effusion associated with multiple nodular alveolar infiltrates, crazy-paving pattern in both apices, and anterior segments of both upper lobes showed filling defects in bilateral lobar pulmonary arteries. There were 2 focal heterogeneous lesions consistent with liver abscesses, measuring 8.8 × 6.5 cm and 2 cm, bilateral peripheral acute pulmonary embolism, with no signs of right overload, and septic emboli (Fig. 1B). Given his poor progress, he was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Ultrasound cardioscopy showed LVEF 60% with no right heart dilation. Deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremities was ruled out by Doppler ultrasound.

Percutaneous puncture and drainage of the liver abscess were performed, and the culture grew multisensitive, ampicillin-resistant K. pneumoniae capsular serotype K1, hypermucoviscosity phenotype (Fig. 1C). In serologies for Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 we obtained IgM negative and IgG positive antibodies, all consistent with recent infection and ruling out acute viremia. Serologies for syphilis, HIV, HBV, and HCV were negative.

The patient was treated with meropenem 1 g IV every 8 h and ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV every 12 h and subsequently with ceftriaxone 2 g IV every 12 h according to sensitivity testing, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, and enoxaparin 60 mg subcutaneously every 12 h during his 6-day ICU stay. Thoracentesis was performed, yielding an amber pleural fluid with pH 7.38, glucose 135 mg/dl, proteins 3.7, mononuclear cells 22.8%, polynuclear cells 77.2%, leukocytes 6,261, RBCs 49,000/mm3, while the culture was negative. On cytology, extensive hemorrhagic foci with polynuclear cells were observed, with no evidence of malignancy. The patient remained in hospital for 60 days, showing clinical improvement after completing 2 months of treatment with ceftriaxone, and was discharged after resolution of the abscess and lung lesions. At follow-up in the clinic 45 days later, the patient was asymptomatic.

KLAS is an emerging infectious disease characterized by the demonstration of a liver abscess with a single microbe, bacteremia, and distant infection. It is endemic in Taiwan, where more than 900 cases have been reported; however, this infection has also been reported in other countries in Asia, and in North America and Europe3–6, possibly because of migratory flows. Up to 50% of cases have been associated with the presence of diabetes mellitus. It is a potentially serious infection due to extrahepatic complications in up to 13% of cases. Liver abscess is usually single and multiloculated, not associated with cholangitis, caused by capsular serotypes K1 and K2, known as hypervirulent clones, which confer it a hypermucoviscosity phenotype, as observed in the strain isolated in our patient.

Liu et al. suggest colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by K. pneumoniae via the portal vein as the primary cause of the liver abscess, after isolating it in the feces of a healthy population1,7. The aggressiveness of this bacterium stems from the magA gene, specific to the capsular serotype K1 that increases resistance to phagocytosis, the rmpA gene regulating the phenotype of hypermucoviscosity, aerobactin, an iron siderophore, and kfu. A positive mucoid thread test determines the K1 and K2 hypervirulence phenotype, characterized by the formation in agar plates of a mucous thread measuring more than 5 mm when the colony is touched with a loop. These characteristics have been published in China in a 6-year retrospective study with 175 elderly people, in which this strain was responsible for 45.7% of the cases, causing a severe inflammatory reaction7. Resistance to antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones has also been detected, and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) production has also been reported in up to 20% of cases8.

A Spanish study showed that the hypervirulent strain was isolated in 5.4% of blood cultures positive for K. pneumoniae obtained during a 7-year period, and of these 30.2% were magA-positive and rmpA-positive serotype K1, the strain most frequently associated with pyogenic liver abscess and secondary septic emboli9. As occurred in our patient, clinical manifestations include fever (93%), pain in the right hypochondrium (71%), and nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea (38%). Raised transaminases and bilirubin are also typical. Hematogenous spread occurs in 10%–13% of cases. The target organ in our patient was the lung, but the syndrome may also present as endophthalmitis, brain abscess, meningitis, spondylitis, osteomyelitis, abscess in the lung or other site, necrotizing fasciitis, etc.10,11 Pulmonary involvement is rare and may occur in the form of septic embolism, consolidations, interstitial opacities, and pleural effusion, while cases of empyema and progression to respiratory distress have also been described11,12. In 72.7% of distant infections, thrombophlebitis of the hepatic veins would explain the passage of the pathogen to the blood and its subsequent spread10. Elective treatment is percutaneous drainage and antibiotic therapy for at least one month. Ampicillin-sulbactam, quinolones, and third-generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone or cefotaxime) may be used. A 4-week course of antibiotic treatment is recommended in the case of single abscess, whereas if multiple abscesses exist, treatment should be prolonged for at least 6 weeks12. Meropenem or imipenem may be used in patients suspected to be infected with an ESBL-producing strain13. Mortality may be up to 10% in cases of liver abscess and 30%–40% in cases of meningitis12.

Our case shows KLAS as an emerging entity that is not endemic to our country, but which may cause clinical deterioration in a patient with bacteremia and septic pulmonary embolisms associated with liver abscess. This entity can cause severe invasive disease, and can lead to septic shock, multiorgan failure, and death. It is therefore essential that it is diagnosed and treated early, using adequate intravenous antibiotic therapy and, if necessary, drainage of the liver abscess. Other distant foci must also be identified promptly.

Please cite this article as: Celis C, Castelló C, Boira I, Senent C, Esteban V, Chiner E. Síndrome de absceso hepático y bronconeumonía por Klebsiella pneumoniae hipermucoviscosa. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:668–670.