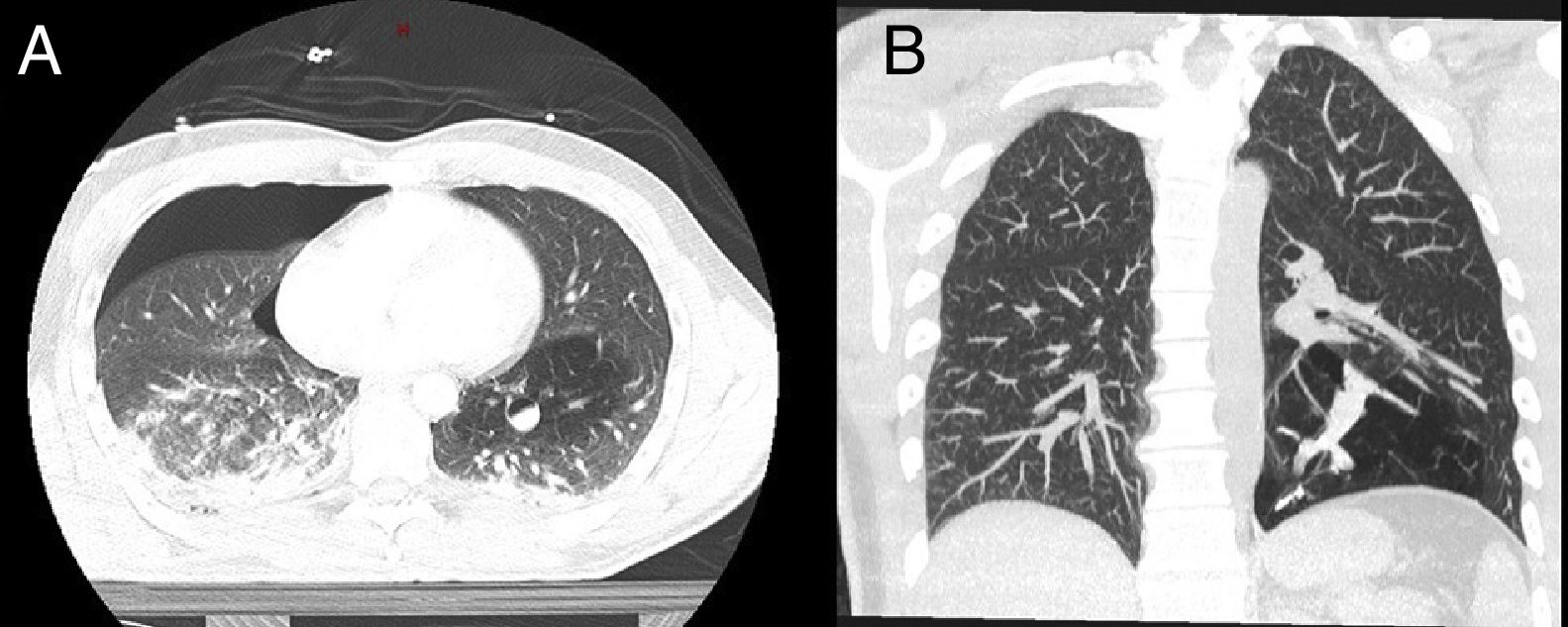

Young adults with no prior disease often undergo their first computed tomography (CT) as a result of high-energy accidents. Incidental findings are difficult to interpret due to the urgent nature of the situation and lack of previous information. We report the case of a patient who was diagnosed with bronchial atresia after high-energy trauma in a traffic accident. A 35-year-old patient was admitted after a high-energy traffic accident. On arrival he presented: BP 100/80mmHg, heart rate 101bpm, respiratory rate 15breaths/min, and hypoventilation of the right hemithorax. There were no signs of cardiac tamponade or hemoptysis. A chest-abdominal CT was performed that showed right pneumothorax, adrenal hematoma, liver contusion, multiple fractures of the right ribs and the right lumbar transverse processes, and a nodular lesion in the right hilum with air-fluid level that showed a dubious vascular communication in the left upper lobe with distal hyperinflation (Fig. 1A). A right chest tube was placed to treat the pneumothorax. Initially, the main hypothesis regarding the nodular lesion in the left lower lobe was that it was caused by vascular aneurysm or pneumatocele, enhanced due to extravasation of the intravenous contrast medium. Within a few hours, the team of thoracic radiology specialists considered the possibility of bronchial atresia, despite this being a rarer and more unusual diagnosis.

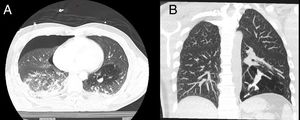

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy performed in the intensive care unit did not reveal any significant bronchial changes or signs of bleeding. Absolute bed rest and continuous hemodynamic monitoring were indicated. However, the patient became anemic, with initial hemoglobin levels falling from 13.4g/dl to 7.6g/dl, but with no signs of active bleeding or hemoptysis. Serial radiographic monitoring showed no changes, so a CT angiogram was repeated 1 week later, confirming the diagnosis of bronchial atresia, and ruling out the presence of vascular lesions (Fig. 1B). Anemia was attributed to the multiple fractures and contusions caused by his injuries. The patient was discharged after 11 days without complications. No new complications developed during the subsequent year of follow-up.

Bronchial atresia is an uncommon malformation characterized by lobar, segmental, or subsegmental bronchial occlusion. Distal lung segments are hyperinflated, and the bronchial secretions are impacted (bronchocele). It generally affects young men, and usually occurs in the left upper lobe. The most common symptoms are fever, cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea, although patients are mostly asymptomatic. Chest X-ray is significant for pulmonary hyperlucency (90%), and hilar nodular lesion (80%).1 On chest CT, impacted secretions, pulmonary hyperinflation, and pulmonary hypovascularity should be pathognomonic. Pulmonary hyperinflation is due to collateral ventilation through the intraalveolar pores of Kohn, the bronchoalveolar Lambert's channels, and the interbronchiolar channels. Lipoid pneumonia may occur if collateral ventilation is insufficient.2 Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is useful for the diagnosis of this entity, but the obliterated bronchus cannot be identified in half of all cases. Diagnosis in infancy is uncommon, and the condition may be confused with congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, intralobar sequestration, or lobar emphysema.

Matsushima et al. described radiological findings in 8 adults and 1 child.3 The most common differential diagnosis are vascular malformations, other malformations with impacted secretions, lung cancer, and bronchial adenoma.

Treatment is conservative when the patient is asymptomatic. Surgery is indicated in symptomatic patients, in cases of repeated pneumonia, in cases in which the presence of malignant lesions cannot be ruled out, and in those in which lipoid pneumonia prevails over hyperinflation.4 Standard segmental pulmonary resection is the surgery of choice because a greater amount of the parenchyma can be preserved, as it must be remembered that this is a benign disease in young patients. The approach of choice is video-assisted thoracoscopy, although this procedure can be difficult due to the fact that the bronchocele normally occurs in the hilum, causing an inflammatory reaction that complicates the resection procedure. In lobar bronchial atresia, lobectomy can replace segmentectomy in order to achieve complete resection.

Our case was a trauma patient in whom the most likely initial differential diagnoses were pulmonary laceration due to an acceleration-deceleration injury, or vascular aneurysm.

No pulmonary contusion or alveolar consolidation were found in the initial CT scan, so lipoid pneumonia could be ruled out. Acquired bronchial obstruction, due to the presence of a foreign body or inflammatory disease was initially ruled out on fiberoptic bronchoscopy, and later confirmed by the absence of any type of neoplastic lesion after 1 year of follow.

In conclusion, bronchial atresia is a benign, uncommon malformation. It is usually asymptomatic and computed tomography helps to guide diagnosis. The differential diagnosis includes vascular malformations, pulmonary sequestration, and lesions with mucoid impaction. The treatment of choice is conservative, and pulmonary resection should be avoided and reserved for symptomatic patients only.

Please cite this article as: Garcia-Reina S, Fernández E, Martinez-Barenys C, López de Castro P. Atresia bronquial diagnosticada incidentalmente tras traumatismo torácico. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019;55:53–54.